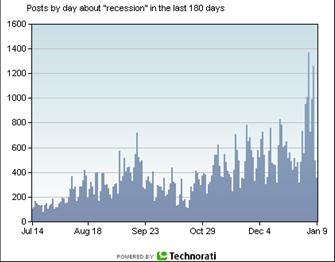

With recession calls becoming more frequent ([1], [2], [3], [4], [5]) it might pay to revisit the indicators that the NBER looks at in determining the turning points in recessions (The fact that NBER put up some new recession-dating-FAQs just a couple days ago might be a leading indicator of sorts).

Figure 1: Posts on “recessions” by weblogs with “any authority”, accessed on January 9, 2008. Source: Technorati.

Recessions Defined

First, let’s recall what the various definitions of a recession are. The oft-cited two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth indicator is a rule-of-thumb. In the United States, the standard arbiter is the NBER business cycle dating committee (or, as it’s now brought to my attention, the “BCDC”), although the authors of the 2004 Economic Report of the President made the argument for a different timing than the NBER arrived at (see this post on that debate).

From the 2003 report:

“In choosing the dates of business-cycle turning points, the committee follows standard procedures to assure continuity in the chronology. Because a recession influences the economy broadly and is not confined to one sector, the committee emphasizes economy-wide measures of economic activity. The committee views real GDP as the single best measure of aggregate economic activity. In determining whether a recession has occurred and in identifying the approximate dates of the peak and the trough, the committee therefore places considerable weight on the estimates of real GDP issued by the Bureau of Economic Analysis of the U.S. Department of Commerce. The traditional role of the committee is to maintain a monthly chronology, however, and the BEA’s real GDP estimates are only available quarterly. For this reason, the committee refers to a variety of monthly indicators to determine the months of peaks and troughs.

The committee places particular emphasis on two monthly measures of activity across the entire economy: (1) personal income less transfer payments, in real terms and (2) employment. In addition, the committee refers to two indicators with coverage primarily of manufacturing and goods: (3) industrial production and (4) the volume of sales of the manufacturing and wholesale-retail sectors adjusted for price changes. The committee also looks at monthly estimates of real GDP such as those prepared by Macroeconomic Advisers (see http://www.macroadvisers.com). Although these indicators are the most important measures considered by the NBER in developing its business cycle chronology, there is no fixed rule about which other measures contribute information to the process.”

The Indicators to Date

Armed with this information, let’s examine the various series. Figure 2 depicts the first two series (both in logs). It’s clear that real personal income has plateaued, if not started to decline — although we do not have December figures. Payroll employment growth has slowed to a crawl.

Figure 2: Log personal income less transfers in 2000Ch.$ (blue) and log payroll employment. Real personal income calculated by subtracting off transfers from personal income, and deflating by the personal consumption expenditure deflator. Source: BEA and St. Louis Fed FRED II.

As has been discussed at length, the BLS firm Birth/Death model seems to lead to overprediction around negative turning points and underprediction around positive turning points. Hence, in Figure 3, I plot both the establishment series (red) and the household series adjusted to conform to the payroll concept (green).

Figure 3: Log payroll employment (red) and log household civilian employment, adjusted to conform to payroll definition (green). Source: St. Louis Fed FRED II and BLS.

In my view, the household series does not provide much solace to those who believe a recession can be avoided.

The next figure (figure 4) depicts industrial production (blue) and real manufacturing and trade sales (red) (both in logs); here the trends are more mixed, although we do not have the November data for the latter series (as noted in this post, industrial production looks like it’s peaked, although it’s conceivable this is just a local maximum).

Figure 4: Log industrial production (blue) and log manufacturing and trade sales, in Ch.2000$. Source: Federal Reserve Board via St. Louis Fed FRED II, and BEA.

The final indicator, mentioned as an adjunct series, is Macroeconomic Advisers’ monthly GDP series. I don’t have access to that series, but have e-forecasting.com‘s series. From the January 4th newsletter, here’s the level of GDP estimate for December.

Figure 5: Monthly real GDP (Ch.2000$). Source: e-forecasting.com.

Output appears to be stabilizing as well, although I do not have documentation for how this series relates to the Macroeconomic Advisers series.

Decoupling, Again

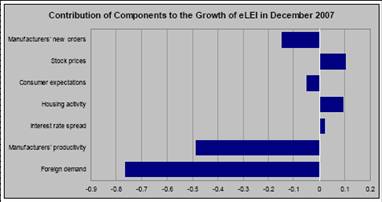

Will the rest of the world save the US economy? Well, e-forecasting‘s index of leading indicators (January 2 newsletter; documentation here), besides indicating a 81% probability of recession, incorporates a large negative effect coming from the foreign demand component. This has been described to me as being based on incoming orders of manufactured goods coming from foreign countries.

Figure 6: Components of the e-forecasting eLEI. Source: e-forecasting.com.

Not good news for the decoupling hypothesis. This is consistent with my earlier skepticism regarding the decoupling hypothesis, and ambivalence regarding whether net export growth could prevent the US economy from going into recession.

Are the Policies of the Past Responsible for the (Potential) Recession of the Present?

One could plausibly say the two recession characterization is unfair, even if technically this is the outcome in the end. After all, the recession that the NBER dates as beginning in March of 2001 is unlikely to have arisen as a consequence of policies (either actual or anticipated) with the Bush Administration. But if we slide into recession in 2008, all I can say is that — despite the talk about fiscal and monetary policy — our actions are constrained by the profligacy of the two Bush tax cuts and the (domestic) spending binge.

To recap what I wrote in October 2006:

The current episode is distinguished from previous ones by a set of constraints on policy that did not exist before 2001. First, using fiscal policy — aside from automatic stabilizers — is much less plausible than it was at the beginning of the last recession in March 2001. As many recall, before the implementation of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001, the Congressional Budget Office was projecting enormous surpluses as far as the eye could see. Even if in hindsight some of those projected revenues were unlikely to materialize because of the transitory nature of the stock options phenomenon, there is no denying that the budget surplus was slightly over 1% of GDP in fiscal year 2001, while in fiscal year 2006, with the economy running at near full employment, the budget deficit is projected to be around 2%. Furthermore, the deficit is likely to rise even if the economy maintains growth at consensus rates. But it’s not only the budget deficit that places constraints on discretionary fiscal policy. The stock of Federal debt held by the public has increased enormously, from $3.3 trillion to a projected $5.6 trillion (end of fiscal years), at exactly the same time that the prospect for even greater funding requirements for entitlements looms on the near horizon. The addition of an enormous new prescription drug entitlement (officially called Medicare Part D) only worsened the long term fiscal position of the U.S. Government. Indeed, GAO estimates that this single provision added $8.7 trillion dollars worth of contingent liabilities to the Federal government’s exposure, fully 50% larger than the estimated Social Security exposure. Hence, borrowing for expansionary fiscal policies — either tax cuts or increased transfers — may encounter weaker demand on the part of foreigners, as well as domestic residents, as these future borrowing needs loom. This in turn means that expansionary effect of budget deficits may be much smaller and costlier at exactly the time that we need the help of fiscal policy.

What about monetary policy? It is an economic truism that you cannot hit two separate target variables with one instrument. With fiscal policy hamstrung, monetary policy needs to make tradeoffs in order to hit inflation and output targets. If energy prices continue their slide, it may be that monetary policymakers will have the leeway to drop the Fed Funds rate. But if, for instance, energy prices do not continue their fall, or a decline in the dollar’s value leads to a rise in import prices, then the Fed will be forced to choose between inflation stabilization and output stabilization. With Ben Bernanke at the helm, I think I know on which side he would err.

In fact, the choice may be more painful than what I have suggested in this scenario. In the wake of the dot-com collapse, monetary policy was successful in spurring economic recovery by encouraging a massive boom in residential investment. With the [nominal] stock of housing at the end of [2005] 45% larger than it was at the end of 2000, it is not clear that a repeat performance is possible. [editorial changes made, in brackets]

These are points to keep in mind as the Administration and Congress consider ways of stimulating the economy (see e.g., this article).

In addition, it is becoming increasingly apparent that the Administration’s laissez faire (that’s the charitable interpretation, see here and here) approach to mortgage market regulation led at least in part to the unsustainable boom in housing markets. The hangover from this boom-bust cycle will likely be with us for a long time; it remains to be seen if we will avoid incurring large fiscal liabilities that would arise from large scale failures of financial institutions.

In this sense, I think a lot of the blame for the depth and persistence of this incipient slowdown will be attributable to the policies of the Administration.

[late addition: 1/10/08, 10:35am Pacific]

Figure 7: Consumer debt to GDP ratio. Source: CMDEBT series from St. Louis Fed FRED II, BEA, and author’s calculations.

Technorati Tags: recession,

payroll employment,

personal income,

NBER,

fiscal policy,

housing.

Very good post. But it is saying nothing about the (long?) duration of the stagnation after the probable recession. In my view, that depends on the interbanking blockage problem.

Opening Bell: 1.10.08

Citigroup, Merrill Seek More Foreign Capital (WSJ) This probably won’t surprise anyone, but word is that Citi and Merrill are both on the hunt for more foreign cash. Merill may get up to $4 billion and Citi’s take could be…

menzie, looking at the raw data available for Q4 of 2007, it looks like it will be modestly positive. It appears the dramatic negative change will not happen. Lag times and the housing boom financial collapse predicted for 7/2008, lead me to believe that a recession, if it occurs, will not happen till late in 08. Your prediction?

With real DPI down in Oct. and Nov.; household employment down in Oct.; industrial production down in Oct.; I posit that the committee will ultimately date the start of the recession in Oct. ’07.

This mess began long before Bush set foot in office, Professor. Household debt — the real problem, here, in my opinion — began rocketing up in the early ’90s, under that other guy:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/fredgraph?chart_type=line&s%5B1%5D%5Bid%5D=CMDEBT&s%5B1%5D%5Btransformation%5D=pcl

Nice try though, sir.

Anonymous was jg.

jg, if the definition of a recession is two negative quarters of GDP growth, then we are not there yet. If you are talking about a down turn, then we may be there. Will it eventuate in a recession? Maybe.

I do, however, agree with you that the down turn started under “that other guy”, often considered a Saint, by those in his party.

Once again, I think Menzie is making his opinion from different graphs than the ones he has posted here. I suspect he regraphs the variable over a time frame of 2006 to 2007 to see the short term trends. Those graphs of ’99 to ’07 are too small to see what the heck is happening Q4’07.

The bond market is telling us not to worry about stagflation. We just need to worry about a straight up recession. The 10 year hit 3.79% yesterday. Yikes!

It seems to me that the Bush adminstration is guilty of robbing us of a tool–fiscal policy–that we might use to offset the coming slowdown. No more, no less.

It seems to me that high home prices, the excess stimulus that they caused, the excess debt accumulation, and the financial engineering that allowed it all to go on is the real culprit.

Despite the bias, a great post.

I remember watching an investment program in the late ninetees on CNBC hosted by Bill Grifith. It had Larry Kudlow and Jim Rodgers on every week, sort of a “McLaughlin Group” for investments. I remember about 1997 or so Jim Rodgers saying that the 10 year would never go below 6% “in our lifetimes”. Kudlow agreed with him. That was the conventional wisdom at the time.

That’s exactly what I thought not too long ago, when the 10 year was above 5%. I didn’t think it would ever go below 4% again. I thought that that was a once in a lifetime occurance.

Now here we are below 4% again. Where is it going to go if there is a deep recession?

All you can say is that at these rates, at least our enourmous deby becomes cheaper to service.

My guess is that the bond market thinks that high commodity prices are growth driven, and if you take the growth away with a US recession, commodity prices should ease.

Of course, if you think that we’re already in a recession, how do you explain $100 oil?

Menzie-

You wish!

jg: Two thoughts. First, if you are focusing on consumer debt to GDP, then — as you will see from the graph I’ve added (Figure 7) — I agree. It begins in the “sainted one” by his party, i.e., Ronald Reagan. Of course, I don’t think one wants to approach analysis this way. It would lead one to date the beginning of our problems with the advent of the Diner’s Club card, or perhaps the lifting of anti-usury laws at the end of the Medieval period.

More seriously, my second point is that consumer debt is largely an inside liability, offset by an inside inside asset. I.e., what is owed by consumers is owed to other consumers via financial institutions within the private sector. To the extent that there is some owed to foreigners, I agree; then we should look to net foreign liabilities, which I’ve discussed at length elsewhere. Another way of looking at this is we should be looking at net household wealth rather than just liabilities.

Luis Hernandez Arroyo: I don’t disagree that financial system issues will be important. However, DeutscheBank (GEP, 1/7) asserts a consumption slowdown of prolonged duration: “The bad news is that the correction in home prices looks to have a good deal further to go, and that the drag from construction will likely overlap with an emerging drag on consumer spending as a result of negative wealth effects associated with declines in house prices. Given that home prices could remain depressed well beyond 2008, we think some associated drag on consumer spending could be with us for several years to come.”

CoRev: Given DeutscheBank’s forecast of 2% for 2007Q4, I doubt the recession will be dated to this year. But the caveat is that NBER’s BCDC will be looking at data many quarters from now in determining the trough. Hence, I leave timing issues to Jim’s econometric methodology.

toddleem: For a discussion of (lack of regulation and) the housing boom/bust, see here.

buzzcut: I didn’t say we were in a recession; just that there’s a good chance (and the prediction markets concur), and that because of the budget deficit, the scope for fiscal policy is circumscribed, the recession will be prolonged.

Buzzcut: $100/bbl oil these days is a function not only of US demand, but also Chinese and rest-of-world demand. There’s also a political risk premium built in.

Rich Berger: No I don’t (wish). I work at a state university, which is in part funded out of state revenues, which are in turn very cyclically-sensitive. You can do that math as well as I can…

$100/bbl oil these days is a function not only of US demand, but also Chinese and rest-of-world demand.

Rest of world demand is being driven by the US consumer. The US consumer is the first, last, and really only consumer there is on this planet.

Okay, we know that most of the Chinese economy is investment driven, not export driven. But why would they keep investing if their export sector tanks?

I read some time ago about how the increasing use of painkillers has both decreased their effectiveness while increasing our inability to tolerate pain. I wonder if the same could be true about the economy. It’s easy to pillory presidents, congress and the FED (and they certainly deserve it) but ultimately aren’t they just providing the American people with the painkillers we want? Easy credit, no recessions, lots of gov’t benefits, etc. And now, when an economy should follow the normal economic cycle everyone wants the “the gov’t” to stave it off. We may be the home of free but we’re pretty far from the home of the free market. It will be interesting to see if and for how long this sort of economic alchemy can last.

because of the budget deficit, the scope for fiscal policy is circumscribed, the recession will be prolonged.

This is somewhat circular logic. You stated that the whole reason we have the deficit in the first place is tax cuts and overspending. Those are economically stimulative policies.

So stimulative, in fact, that they have allowed the deficit to fall over the last 4 years!

So, we’ve had fiscal policy driven growth. Why would we think that MORE fiscal stimulus is the answer to faltering growth?

And, really, why would the deficit where it is today be an impediment to more fiscal stimulus anyway? If we needed to go to a $500B deficit, or even $1T, do you really think that Dubya would balk at that? Would the Democrats balk?

I predict that the Q4 numbers are going to come in well ahead of your “consensus” forcast. Q1 and Q2 will be brutal, but maybe not technically a recession.

I hate to have to point it out but Constitutionally the President does not appropriate one cent and, except for enforcement of the law and jawboning, has no effect on the economy. Any recession must fall to congress and the FED. The recession of 2000 was because the Republican congress failed. The current economic problems are because the Democrat congess is failing.

I did get a chuckle out of the term the “Administration’s laissez faire”. Anyone who believes that the federal government at any time since since 1927 even comes close to laissez faire is seriously deluded.

I B crushed by the “saintly” retort by Menzie.

Buzzy, comrad, (truly I feel we are drifting closer together) do you or do you not feel that 1.6B Chinese are burning up more oil …as their basic daily diet expands from raw beans and rice?

It could be a slight exaggeration to claim that “the US consumer is the first, last, and really only consumer”…check the recent missive from GM’s Wagoner for confirmation of this detail.

Calmo, your attitude about the Chinese consumer is one I’ve been hearing from businessmen since I first graduated from college in ’95. Everyone at that time was infatuated with “1 billion (potential) consumers”.

It certainly has not worked out as well as all the pioneers had hoped. My experience with my first employer back in the late ’90s was that the Chinese bought our product once… and then copied it. In fact, we were at one time interested in finding a local manufacturer for our product (distillation trays for refineries), but balked at the intellectual property implications.

And there’s only 1.3B chinamen!

our actions are constrained by the profligacy of the two Bush tax cuts and the (domestic) spending binge

In other words, cutting taxes and increasing spending earlier prevents us from cutting taxes and increasing spending now. However, if the latter would really be all that effective as a fiscal stimulus, wouldn’t it have worked before, in 2001-2002? Wasn’t there a recession in 2000; would it have made sense to have no fiscal stimulus then in order to have fiscal stimulus now? Or are you arguing that the nature of the tax cutting and spending was inappropriate?

Also, while the surplus in 2000 did give a lot more room to use fiscal policy to address the recession, we can’t forget about the recession of 1991. That one ended up being mild and short despite a far more crushing deficit– 4.5% of GDP in 1991 and 4.7% in 1992, with debt held by the public a much higher percentage than now, and rising. (By contrast, debt held by the public actually decreased as a percentage of GDP from FY 2005 to FY 2006.) That actually didn’t stop President Clinton from promoting a fiscal stimulus package at first, albeit one that got defeated. And I see that the economy recovered without fiscal stimulus.

http://www.cbo.gov/budget/data/historical.pdf

So, one natural question is: Did the surplus in 2000 make it so much easier to fiscally stimulate our way out of recession in 2001-2002 than the huge deficits from 1990-92? If not, why would we expect there to be such a huge difference with a deficit now half as small as that of 1991-92?

Buzzcut, that’s true as far as it goes, but so far not even the Chinese have figured out how to copy oil.

Given the growth rate of the Chinese economy the past few years, isn’t it naive to suggest that something is premature now because it was premature in 1995? The Chinese are poised to surpass the U.S. as the world’s #1 producer of CO2 emissions (an “honor” I am happy to cede to them), and there must be something causing them to burn all those fossil fuels.

The President presents the budget to Congress. Also the idea that ANYTHING economy-wise can be blamed on the Democratic Congress a few months, is laughable.

Menzie;

That’s a very careful and thoughful analaysis. I’d like to point out a technical problem, however, that I pointed out in late December in response to one of Jim’s posts (“The Bears Have to Wait Another Quarter.”)

In evaluating the latest economic numbers, you are mostly looking at unrevised, first-release data. The BCDC declares recessions quite some time after the fact; one of the benefits of their hindsight is that the data have been revised, sometimes substantially. It’s therefore hard to say to what degree the latest data are consistent with a recession without knowing what *first-release* data looked like at the start of previous recesssions. I have seen little or no formal work on this. However, in some previous work with Orphanides, we looked at revisions of real GDP around business cycle turning points. We found that figures tend to be revised up at peaks and down at troughs. That’s what you’d expect if the peaks and troughs are based on the revised series. That also makes turning point detection harder than many people realize.

Simon van Norden: You’re right. I should have linked to this post, which discusses the issues you mention. They are important — which is why I focused on the fact that BCDC won’t make a determination many months from now.

For those who are having difficulty understanding countercyclical spending, consider the case in which the nation has decided that a bridge needs to be constructed, but the precise timing has not been decided. Does it make sense from the standpoint of spending as few tax dollars as possible to start work (a) when economic activity is at its peak, workers are scarce, and wages and the costs of materials are high, or (b) when economic activity has fallen off, a number of workers are idle, and wages and the costs of materials are low?

This is a no-brainer, folks. If one really does believe in limited government, then countercyclical policy is a part of it.

Given the growth rate of the Chinese economy the past few years, isn’t it naive to suggest that something is premature now because it was premature in 1995?

A few things:

1) How much do you trust that growth rate? Is it accurate?

2) What is the growth being used for? If its just building up an export sector that is catering to US consumers, the Chinese are going to do WORSE than the US if there is a downturn. The part of their economy that is export oriented will crater, as well as the part of the economy that is based on investment into the export sector.

This is not just a Chinese problem. The Germans, Japanese, Koreans, Taiwanese, and many others base their economies on stoking exports at the expense of internal consumption. This is what I meant by US consumers being “the consumers of first, last, and only resort”.

Real US nonpetroleum imports peaked at $49,310 real 2000 $ in July of 2006. In November of 2007 they were $44,515 — about a 10% drop.

So over the last 16 months we have seen a very significant drop in US imports, yet it has yet to show up in slower growth for China, Germany, etc..

What do you suspect is the lead or lag time we should expect before this very significant drop in US import growth shows up in the Chinese, German, etc., growth rates?

Sorry I looked at the wrong column. The numbers I quoted above are the real trade balance, not the real import data.

Buzzcut – I trust the statistics on Chinese growth every bit as much as I trust those on U.S. growth. 😉

According to Wikipedia, 21 percent of the Chinese exports went to the U.S. in 2004 (the only year they cite). So a recession here would hurt the Chinese economy, but it’s anyone’s guess whether it would bring it down. (Actually, it’s anyone’s guess whether whether a recession here would even strongly affect purchases of Chinese goods, since in many product lines it’s increasingly difficult to find non-Chinese alternatives. People are going to quit buying new cars before they quit buying new shoes.)

Surprisingly – to me, at least – China’s trade surplus isn’t large. Without their massive surplus from trade with the U.S., they’d have a sizable deficit.

pianoguy (jazzorClassical?), China’s trade with Europe has increased as trade with the US has ebbed, but according to Sester China’s trade surplus is still formidable.

Buzzy is right to question the accuracy of the China numbers (even population) but it is hard to believe the simplistic tight coupling thesis given China’s store of US tbills and the US’s dependence on the kindness of strangers to help balance the CAD.

Looks to me like financial co-mingling at the moment with Meryl and Citi, pan-handling in Shanghai.

Not much coverage lately about the modernization that those rudimentary Chinese banks need to acquire the sophistication of the US Financial heavies.

I recognize spencer’s 2nd post as an honest correction, but it has the effect of driving the nail of his 1st post home: the net trade figures being more important than the falling import numbers.

Last thing: I don’t know if citing a 2 recession administration is the most devastating thing one could claim about GWB’s incompetence. Fair enough that he inherits the first one (from a Repub Congress as much as Clinton), but that he buries the country in debt/corruption and sets the stage for a monstrous 2nd downturn (for which the expression “recession” seems entirely understated and euphemistic) needs to be highlighted as his real legacy.

Menzie, Thanks for an informative and amusing post.

I agree that net exports will not prevent recession but may help lead the US economy out of the recession/stagnant growth period.

Given the tendency of the Bush II regime to throw money at friends, and generally mismanage assets (natural, diplomatic, etc.), isn’t there a silver lining to a ballooning deficit that prevents this administration from spending even more money on negative social return items?

Thought I’d share some rhetoric from the Reagan era of massive borrowing.

Le Monde informs me that the US posted record import and record export values in January. The import record is largely due to the price of oil.

I have always thought that harassing and isolating the countries with the world’s 2nd and 3rd largest reserves of light, sweet crude oil, may ulimately contribute to higher crude oil prices.

With luck, monetary policy can correct these Imperial Mistakes even if monetary policy is not exactly the appropriate tool for taming US colonial ambitions and entitlement.