The tax policy chapter of the ERP is quite interesting, in part because I have a sense of deja vu [1], [2] when reading the cross-country/international sections.

From Chapter 6 Chapter 5 of the Report [large pdf!] (p. 135):

The efficiency of the business tax structure in the United States is particularly

important as other countries undertake major corporate tax reforms. Capital

is mobile across international borders, and the business tax environment is

important in ensuring that the United States continues to attract investment

from abroad, and that U.S. firms can compete effectively in foreign countries.

In the mid-1980s, the average statutory corporate tax rate (weighted by

GDP) across OECD countries was 44 percent. The U.S. tax reform of 1986,

which reduced the corporate tax rate from 46 percent to 34 percent, made

the United States a relatively low-tax country at the time of the reform. Since

that time, however, the OECD-average corporate tax rate has fallen below

that of the United States. These comparisons refer to statutory tax rates. The

United States has relatively generous accelerated depreciation provisions and

a multitude of business-level exemptions and deductions that reduce the

tax burden on investment below the statutory rate. However, the effective

marginal tax rate on corporate investment is still high: compared to other

G7 countries (France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, Italy, and

Japan), the United States imposes an above-average marginal effective tax

rate on corporate investment for domestic debt and equity holders in the

top individual income tax bracket. In contrast, the U.S. average corporate tax

rate (the total amount of corporate taxes paid as a percentage of corporate

operating surplus) is low relative to other countries. This fact highlights the

inefficiency and complexity of the corporate tax system. The marginal tax rate

represents the additional tax burden a firm faces when it undertakes a new

investment; therefore, it is the relevant tax rate for new investment decisions.

This distortion is larger in the United States than in other countries. Despite

the larger distortion, the corporate tax raises less revenue in the United States

than in other countries, as evidenced by the fact that the average tax rate

is lower. The implication is that investment incentives could be improved

without a reduction in government revenue.

Two points I want to discuss:

- Is it really true that the US marginal corporate tax rate is significantly above that of other OECD and G7 economies?

- Is capital really highly mobile across borders?

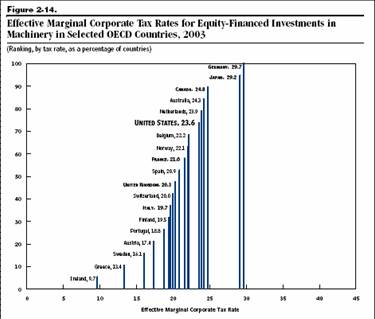

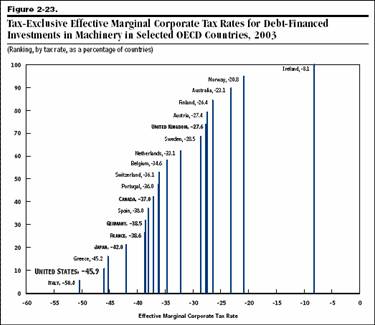

For some authoritative analysis, I look to the CBO’s 2005 report Corporate Income Tax Rates:

International Comparisons [pdf]. Figures 1 and 2 present the marginal effective corporate tax rates for equity and debt, respectively. The pictures are not completely in agreement with the points in the ERP — although one must admit that there different studies will come to different results, given varying assumptions.

Source: CBO, Corporate Income Tax Rates:

International Comparisons.

Source: CBO, Corporate Income Tax Rates:

International Comparisons.

Note that the calculated marginal rates differ depending on type of capital and the measure of inflation; I’ve only graphed the ones for machinery.

(Digression: On the other hand, the wide divergence between the equity and debt marginal rates confirms the assertion that the current tax code probably leads to inefficiencies and dead weight losses.)

On point 1, I don’t think the evidence I am aware of strongly supports their conclusions that the US is at the top of the tax rate distribution.

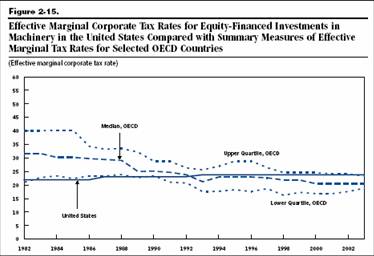

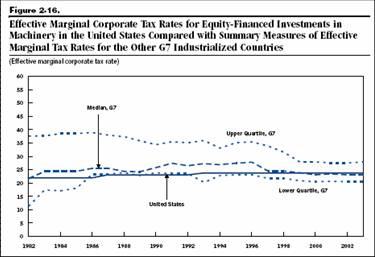

The next two figures lead me to my thoughts regarding point 2.

Source: CBO, Corporate Income Tax Rates:

International Comparisons.

Source: CBO, Corporate Income Tax Rates:

International Comparisons.

What I find of interest is that while the latest US effective marginal rate is at the upper quartile of the OECD distribution, it is at the median for the G-7. To me, this is of interest because the non-G-7 OECD countries are smaller, in GDP terms, than the G-7. This suggests to me that policymakers in these non-G-7 OECD countries have lowered their marginal tax rates because capital is more mobile for these smaller economies. But for the larger G-7 economies, capital is less mobile, so there is greater scope for keeping tax rates at different levels than that in other countries.

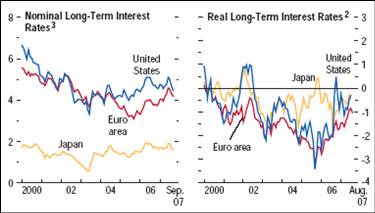

In this age of globalization, it seems strange to assert that capital is less than completely mobile. But just a quick glance at long term interest rates, relevant for physical investment decisions, should persuade people that even financial capital is not fully mobile. Consider the right hand graph of the figure below.

Excerpt from Figure 1.3 from Chapter 1 from IMF, World Economic Outlook, October 2007.

The inflation measure used here is kind of odd, but using inflation indexed yields also confirms the fact that real interest rates are not equalized (see Chart 1.15 in this post). And that’s for government debt. Think about how heterogeneous private debt is.

The more econometrically inclined can refer to this paper. While Eiji Fujii and I find some evidence of real interest parity (RIP) holding more at longer horizons than short, the evidence is by no means conclusive that it holds exactly, when the United States is involved.

The policy implications are potentially profound. When capital is not perfectly mobile, the labor share of the burden of capital taxation can be lower than what is implied when it is assumed that capital is perfectly mobile (see this working paper). Another path to overturning the conventional wisdom would be to assume that domestic and foreign goods are imperfect substitutes (see this article).

Bottom line: One should think about marginal corporate tax rates, and how they vary across types of capital. And maybe one should worry about rates very high relative to other contries’ rates. But it’s probably not appropriate to assume perfect (physical) capital mobility for large, industrial, countries.

Separate observation: As a non-public finance economist, I wonder what this paragraph means. Suggestions welcome (p.121):

The tax cuts of 2001 and 2003 significantly lowered the tax burden on

labor and capital income and reduced distortions. The dividend and capital

gains rate cuts enacted in 2003 had an additional benefit to the economy

by improving the efficiency of the tax structure. By reducing the existing

preference for corporate debt financing over equity financing, these tax

cuts reduced the distortion of corporate finance decisions and improved

corporate governance.

I think they must have a different idea of “corporate governance” than I have. But I readily confess my ignorance.

Technorati Tags: Economic Report of the President,

Council of Economic Advisers,

corporate taxation,

capital mobility,

real interest rate,

globalization.

I believe that the corporate governance issue is the following. Lower tax rates on dividends encourages dividends and reduces retained earnings. This then allows for more efficient investment because firms are less likely to invest in their own relatively low-return projects. Instead they release the funds to the capital markets where it goes to the highest returning projects.

rana: Thanks. OK, I see. For me that’s what I would term an optimal capital structure question a la Modligliani-Miller, in the context of differential tax treatment. I was surprised by the statement because corporate governance in terms of transparency of holdings of, say making subprime loans, or risk management of asset-backed paper, hasn’t seemed to me something to brag about.

Great post, but it’s Chapter 5, not Chapter 6, no?

Translating:

“The tax cuts of 2001 and 2003 significantly lowered the tax burden on labor and capital income and reduced distortions.”

This is a lie, since they were at best deferred tax liabilities, so let’s just declare it fluffing and go onward.

“The dividend and capital gains rate cuts enacted in 2003 had an additional benefit to the economy by improving the efficiency of the tax structure.”

People are less likely to attempt to dodge paying capital gains taxes at a lower marginal rate, so only the really big people did so, and they were more imaginative in doing so.

Since this also doesn’t relate directly to “corporate governance,” we’ll let it ride as well.

“By reducing the existing preference for corporate debt financing over equity financing, these tax cuts reduced the distortion of corporate finance decisions…”

By making it easier to issue equity, we allowed firms to substitute equity issuance for debt. This is both (1) in keeping with the “Ownership Society” mantra and, more relevantly for our purposes, (2) makes it more likely that the shareholder pool will expand (though the concentration at the top may also deepen, but we won’t consider that).

“and improved corporate governance.”

She just above, without the parenthetic. More shareholders–or, as they appear to be arguing, more concentration of the firm’s capital structure in equity–causes a greater alignment of the interests of the shareholders and the management of the company. (Companies that have heavy debt burdens must pay those debts first; companies that are weighted more toward equity have only themselves to blame if the shareholder is not happy with the return on her investment.)

rana’s argument also applies, though here the substitution effect is specifically that (e.g.) $500,000 that would have gone to pay interest on a debenture now goes to pay a dividend on an equity.

In Rana’s argument, you have to make the assumption–absent from M&M for what I consider obvious reasons–that holders of debentures are less interested in the company being run properly than shareholders are.

(You could make that argument, based on the idea that after that 10-year bond matures and the debt holder is paid back, they don’t care that the company remains an “ongoing concern,” and that the stock price is based on infinite growth assumptions [PV of all future cash flows, etc.], but I’m inclined to discount that. YMMV, as rana’s appears to do.)

If you simplify the argument to “aligning the interests of the company with the shareholders,” then fewer debt holders becomes definitionally better “governance.” And saying, “not owning money to bondholders” doesn’t have the same ring.

Ken Houghton: Thanks for the clarification. I see — it’s the alignment issue. Well, as I recall stock options were also a stunning success in aligning executives’ and owners’ interests…

Yes, you are right — it’s Chapter 5. Fixed now.

Rana is correct on the rationale for the corporate governance remark. The issue is that contra what one would expect under M&M it does seem to matter whether companies pay dividends, all things being equal. There are agency issues, and a host of other factors which are fingered, but empirically it seems real executives and shareholders respond differently than M&M suggests they should. Steve Galbraith did some good work on this at Morgan Stanley, but Rob Arnott has some easily accessible papers on it at his firms website, Research Affiliates.

This leads to counterintuitive findings such as companies that retain earnings grow their earnings slower than those with higher payout ratio’s.

I would have preferred that they merely made dividends deductible at the corporate level, but politically it sounds like a giveaway to corporations, while dividend tax relief appeals to a particular constituency.