Ignore the newspaper reports about the short term forecasts; that’s old news, since these White House forecasts were made in November (and hence, it’s not fair to compare these forecasts to current forecasts, as has been done in some journalistic accounts). And ignore the chapter on housing markets — there’s not going to be any discussion of how inadequate regulatory oversight (to put it mildly) might have contributed to this debacle. The interesting stuff is in the discussion — or lack of discussion — of certain international economics issues (no Renminbi!).

Economic Report of the President, 2008 [large pdf!]

First, in the macroeconomic outlook chapter (Chapter 1 [pdf]) (pp. 35-36):

Real exports of goods and services grew 8 percent during the four quarters

2007, the fourth year of annual growth in excess of 7 percent. The pace of

export expansion reflects rapid growth among our trading partners, expanded

domestic production capacity, and changes in the terms of trade associated

with exchange rate trends between 2002 and 2006 that made American goods

cheaper relative to those of some other countries…

…Real imports grew 1.4 percent annual rate during 2007, the slowest pace

since 2001. Real imports of nonpetroleum goods grew 1.2 percent during

2007, also the slowest rate of increase since 2001. Real petroleum imports have edged up 2.5 percent during 2007, while nominal imports surged 49 percent due to rising oil prices. The rise in oil prices has been less of a drag on the U.S. economy than similar rises have been because it has been offset by the strong growth in foreign economies, which has boosted U.S. exports…

Here is what I find of interest. While it is true that exports have surged in recent quarters, over the previous quarters what is generally acknowledged is that US exports were below trend. In addition, implicit in the analysis is the fact that if rest-of-world growth slows down, then all bets are off.

Moreover, I’m not sure I understand the argument that oil price increases have been less of a drag this time around. Perhaps it’s a matter of semantics. I think it would be more accurate to say (given that the import share of total oil consumption is greater than in previous episodes), the effect is greater, but that rest-of-world growth (which has partly driven the oil increases) has served to offset that negative effect. In other words, the totality of the oil price effect, taking into account the source of the increase, is less than in previous episodes (which were driven by supply shocks).

[Late Addition, Feb. 20, 5:45pm Pacific] Steven Braun confirms my interpretation is correct, and then points me to Box 2-1 which I should have read more carefully:

…The increase in real GDP growth among our trading partners probably caused an increase in both the demand for oil and the price of oil, and also an increase in U.S. exports to our trading partners. …

An increase in real output growth among our trading partners of about 1 percent can be expected to increase our exports by about 1 percent as well. The cumulative 9 percent higher growth among our trading part-ners (2.1 percent for each of 4 years) could thus have generated as much as $120 billion per year of exports. In comparison, the $40-per-barrel oil price increase added about $150 billion per year to the Nation’s bill for oil imports (at 3.7 billion barrels of oil per year).

[End late addition]

My rejoinder here is that if the United States had pursued a policy of reducing oil dependence by way of a gasoline tax, the net drag would have been even less. (Of course, like last year’s Report, the phrase “gasoline tax” is nowhere in sight [0], [1] [pdf], although “Pigovian tax” makes it into the document in a different context).

More illuminating is the following passage. From the same Chapter, p. 37:

The current account deficit (the excess of imports and income flows

to foreigners over exports and foreign income of Americans) averaged

5.5 percent of GDP during the first three quarters of 2007, down from

its 2006 average of over 6 percent. The decline in the current account

deficit reflects strong export growth and moderate import growth, although domestic investment continues to exceed domestic saving, with foreigners financing the gap between the two.

Unlike previous years, there is no statement on how that gap is being financed by foreigners (e.g., see this discussion)… Fortunately, the virtue of the ERP is the wealth of statistics in the back of the document. There one can see in Table B-103 that 17.6% of the gross inflows in the first 3 quarters of 2007 are “official” in nature. Of course, that is an estimate, which will likely be revised as ostensibly private transactions get recategorized as official.

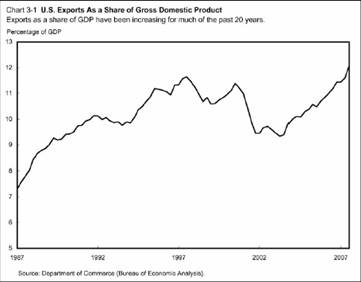

In Chapter 3 [pdf], there is a return to the theme of surprising export growth. Chart 3-1 certainly seems to confirm the characterization of surging exports:

However, extending backawards the sample, and adding in imports (both total and ex.-oil) yields a slightly different perspective.

Figure 1: Exports (blue), imports (red) and imports ex.-oil (dark red) to GDP ratio. NBER recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA, NIPA release of 30 January 2008, and author’s calculations.

The first observation: There have been other periods of rising exports to GDP ratios. Notice that during the previous episodes of commodity price booms in the early and late 1970s, the nominal export share of output increased at even a more rapid pace.

Second observation: the import to GDP ratio — even excluding oil — rose earlier, and to higher levels. The reason this is of interest is that one of the defining features of globalization is vertical specialization, namely the import of parts to produce exports. This casts the surge in exports into a different light, even if we don’t know the extent of vertical specialization [2]. Third observation: data released after the writing of the ERP suggests the export surge is ending.

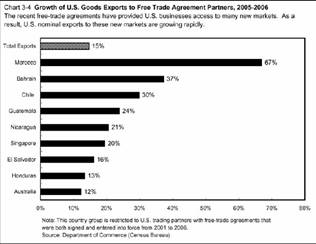

Finally, the authors provide a rousing defense of the Administration’s push to negotiate FTAs.

…Recent research shows that in the short run, the average FTA has increased trade between bilateral trading partners by 32 percent after 5 years, 73 percent after 10 years, and 114 percent after 15 years. After 15 years, the average FTA appears to have had no additional effect on trade growth. Therefore, the long-run effect of the average FTA has been roughly a doubling of trade between the two trading partners. In the case of recent U.S. FTAs, nearly all of the tariff cuts and nontariff liberalization occur early in the agreement, and later stages have more modest phase-outs. As a result, we may expect to see much of the increases in trade coming in the

first 5 to 10 years of the agreement. As is evident from Chart 3-4, U.S. export growth to recent FTA partners in 2006 from 2005 has, for most countries, been higher than total U.S. export growth. Overall, the FTA partners have been major contributors to the growth in exports. In 2006, the United States exported goods to more than 200 economies. Exports to our 13 trading partners in the FTAs that had been signed and implemented through that year accounted for one-third of the growth of U.S. goods exports between 2005 and 2006.

The argument is summarized in Chart 3-4.

However, it is useful to put things in perspective. Exports to countries with whom the US implemented an FTA in the 2001-06 period accounted for 5.76% of exports for the first 11 months of 2007 (author’s calculations based on November 2007 release). Of these exports, 2/3 are accounted for by Singapore and Australia, not the Guatemalas, Nicaraguas, El Salvadors and Honduras of recent note.

This is not to argue that FTAs are not worthwhile pursuing [3]; merely that one shouldn’t overstate.

The one argument that does trouble me somewhat is this one (p. 95):

While trade liberalization may lead to job loss in some import-competing sectors, it also creates jobs in the industries that produce the goods and services the United States exports and in industries that use imported inputs, and the benefits to the economy resulting from trade liberalization are far greater than the costs. Increased trade does, however, adversely affect some workers. The President recognizes that these workers need help with retraining and

reemployment and has called for a reauthorization and reform of the Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program to meet the needs of these displaced workers. The Administration is committed to supporting effective and improved trade-adjustment assistance to workers who are displaced due to import competition.

This is a laudably realistic admission of some of the unwelcome byproducts of trade integration, I do wonder about how sincerely the “reform” of TAA has been pursued. How credible can this commitment to helping out displaced workers be if, for instance, service workers are excluded? (see this CRS report for an analysis of how many non-manufacturing workers might be eligible, and this IIE Brief on the nature of required reforms.)

Other coverage: OMB Watch and WSJ Real Time Economics.

Technorati Tags: Economic Report of the President,

Council of Economic Advisers,

current account deficit,

exports,

free trade agreements,

Trade Adjustment Assistance.

I heard an analysis that seemed to ring true the other day. We are not off-shoring jobs solely because its cheaper. But more importantly because we lack the technical resources to do them, human capital. Simply look at the number of engineering graduates the USA is producing vs. the number China is producing. No wonder we are losing.

Primero!

JS, that analysis is incorrect. Asian schools churn out engineering graduates, yes, but all countries come to US schools when they want an engineer who can actually solve a problem. Asian schools promote rote memorization, and that’s the graduate they get.. not someone who can take disparate (perhaps even seemingly uncorrelated) data, synthesize it, and craft a solution on the fly.

Quantity does not substitute for quality.

“But more importantly because we lack the technical resources to do them,”

My friend, you have been reading too much IBM/Microsoft/Intel propaganda.

Do you have any idea how many unemployed engineers we have? My wife’s nephew just graduated in engineering, tops in his class, one year later, a clerical job 60 miles from home.

My job went to India in 2001. Do you think I just woke up and forgot how to do my job? )h yeah, with 4 years of grad school I am overqualified for anything.

My nephew, graduated law school two years ago. Yep, you guessed it, no job.

This country, the last 7 years has basically created NO private sector jobs. 40% of the jobs created in California were in real estate.

You need to cruise down the aisle of your local Barnes & Noble or Borders. They used to have row after row of technical books. Now they have 1 1/2 racks. No interest because there are no jobs.

Maybe you missed it when it went around on ytube about the seminar for employers about how to eliminate qualified US candidates legally.

Sam Palmisanno fired 50,000 US workers since taking over. He hired 73,000 Indian workers. Do you really think they are smarter or better qualified? The graduates you refer to over there come from diploma mills, not engineering schools.

We are losing because we have been sold down the drain by labor arbitrage, not any skills gap.

When I used to work for AT&T, we basically set up the Internet as we know it and you think overseas labor is smarter than us?

We are losing because AT&T CLOSED BELL LABS and shipped it offshore. That is why we are losing.

Do you really think engineers in Viet Nam are better qualified to design autos than US engineers? They don’t even have cars.

We are losing because of the Sam Palmisannos and Bob Nardellis of the world, not unqualified US workers.

jdh: I seriously doubt US net exports or the US net exports/GDP ratio have “stalled”.

me: I hear ya. Unfortunately, the economic growth literature suggests that income polarization and temporary labour market mismatch are natural characteristics of the kinds of shocks hitting the US and global economies: IT technology and freer trade.

I suppose it won’t help much to suggest that at the end of the day, the US will ultimately be collectively more wealthy. I can also suggest about 3 major reforms that would have prevented the current painful stagnation and labour market mismatch but that doesn’t really help with the current situation either.

E. Poole: I’m afraid it’s Menzie Chinn, not JDH, that’s the author of this post.

To your point, please see Figure 3 in this post, for a picture of how exports (not net exports) have slowed. Net exports — well if we go into full blown recession, I agree. Then oil prices will decline as will imports. But 2007Q4 advance figures (Figure 2 in this post) does not suggest continued improvement over the short term.

“I heard an analysis that seemed to ring true the other day. We are not off-shoring jobs solely because its cheaper. But more importantly because we lack the technical resources to do them, human capital. Simply look at the number of engineering graduates the USA is producing vs. the number China is producing. No wonder we are losing.”

Posted by: JS

In which case US engineers would be seeing higher salaries, and fresh graduates would have a bounty of good, high-paying job offers. Is that the case?

What strikes me is the growth in net foreign borrowing, which seems unsustainable at current levels. Globalization can lead to growth in trade relative to GDP, but I see little reason why it should result in greater borrowing relative to GDP. In light of this, the current efforts to increase U.S. demand seem misplaced – we seem to have a large excess of aggregate demand, since we are consuming 5%-6% more than our income annually. Why should we want to maintain this borrowing? Why is there no analysis of the reasons for the growth in borrowing?

Menzie Chinn wrote: E. Poole: I’m afraid it’s Menzie Chinn, not JDH, that’s the author of this post.

Yes, I noticed the error a few seconds are having posted. Should have also known by the subject matter…. While I am at it, apologies for not replying more promptly. May I blame the fine red print? hehe

Even if the US avoids a recession and sits in that politically toxic 0-2% real growth band, I would still expect net exports to increase because the US dollar continued to decline well into late 2007. The stylized facts supporting past J-curves suggest that both export growth opportunities and import substitution require many months, if not years to be fully realized.

Furthermore, recession or slowdown–in some respects that difference is immaterial–there is clearly a re-structuring of the US economy going on as productive assets flee consumer durable sectors. These liberated, and presumably now attractively priced workers should be successfully re-deployed but with some kind of time lag. Domestic wage adjustments in the form of declining unit labour costs should reinforce recent real exchange rate declines.

The one wild card is oil.