Currently, net exports are one of the few bright spots in the US economy. As Krugman points out, this is the one area where monetary policy is proving effective: by driving down the value of the dollar, expenditure switching is being induced.

Figure 1: Broad Trade Weighted Value of the Dollar, from January – March 2008. Source: Federal Reserve Board via FRED II, accessed March 17, 2008.

So, dollar decline is a good thing, given that several of the other channels of monetary policy have been short-circuited. That being said, there are several constraints to this channel that should be mentioned.

- Exchange rates depend upon the policy rates of multiple central banks, not the least the ECB.

- Foreign exchange intervention is has only limited efficacy in influencing exchange rates over sustained periods, unless coordinated and signals changes in monetary policy.

- Not all US goods and services are highly tradable.

Multiple Central Banks. Consider first the dollar and the euro. In Figure 1, the log trade weighted values of the two currencies are plotted.

Figure 2: Log nominal trade weighted value of the USD against major currencies (blue), and nominal trade weighted value of the EUR against other industrial country currencies (red). Source: Federal Reserve Board via FRED II and IMF International Financial Statistics, accessed March 16.

Returning to the first point, it bears repeating that the dollar’s value is a function of US variables relative to rest-of-world variables, whether it be monetary or Taylor rule fundamentals that are relevance.

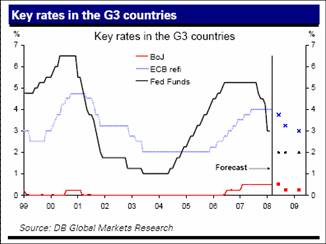

Inspection of short term policy rates makes explicable — at least in part — recent dollar weakness.

Figure 3: Actual and forecast policy rates. Source: Deutsche Bank, Global Economic Perspectives, March 10.

What the forecasts in Figure 2 also highlight is that there are bounds on how far the dollar can fall. As euro area policy rates fall, the dollar will tend to stabilize (although many other factors will continue to push the dollar downward, including possibly the departure of the GCC states from the dollar peg).

Forex Intervention. There has been some discussion of intervention [0]. Here I do not see this as a substantial constraint on dollar depreciation. That’s not because I believe foreign exchange intervention has no effect (see the discussion of the empirical literature on foreign exchange intervention here); rather effective intervention on freely convertible currencies requires the cooperation of major central banks. So we would need to know the motivations for central banks to intervene.

It’s not clear that the appreciation of the euro has quite the impact on Euro Area trade flows that comparable shifts in the dollar has on US trade flows; hence the impact from this channel of an appreciating currency on Euro Area GDP might be less than what one would glean from extrapolating from the US experience. Admittedly, the evidence on what exactly the price and income elasticities for Euro Area trade flows is not particularly developed, in part because of the relative youth of the euro area, and the likely structural changes attendant monetary union.

A quick eyeballing of the data suggests that there is a link between the euro (deflated by either CPI or by unit labor costs), lagged two years, and the Euro Area net exports to GDP ratio.

Figure 4: Euro Area Net Exports to GDP ratio (blue), and log real trade weighted euro exchange rate, CPI deflated (red), and unit labor cost deflated (green), lagged two years. Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics, accessed March 16, 2008. Note: the currency basket for the CPI deflated index is wider than that for the unit labor cost deflated

However, the extant econometric estimates suggest a more muted response of trade flows to exchange rates than in the US case [1]. Dieppe and Warmedinger (2007) provide some estimates of extra-Euro Area export and import elasticities. The estimation, couched in terms of error correction models, and incorporating homogeneity of exports to world demand for imports, and homogeneity of imports with respect to domestic (Euro Area) demand, suggests the sum of the absolute value of (relative) price elasticities is about 0.80. But we know that pass through of exchange rates into prices is typically substantially less than unity; hence, a back of the envelope calculation suggests a sensitivity of trade flows to exchange rates much less than that required for the Marshall-Lerner conditions to hold. Similarly, in a occasional paper from 2004, Anderton, di Mauro and Moneta cite relative price elasticities and pass through coefficients that imply (approximate) export elasticities with respect to exchange rates of about 0.25, and import elasticities of about 0.49. These results might explain the equanimity with which some European policymakers greeted the euro’s ascent. So, for now, no obvious floor to the dollar.

(Note, there are other channels whereby which changes in currency values could have an effect on output (see for a discussion of Europe and these linkages Lane and Milesi-Ferretti, 2007 [pdf]). The channel focused on above is on trade flows. Euro appreciation, with the Euro Area in a net creditor position, could a net capital gain or loss, depending upon what triggers the dollar decline. Hence, Euro Area policymakers might have other motives for halting euro appreciation.)

[Update: for discussion of the possibility of Japanese intervention, see NYT March 18.]

Tradability of US output. Finally, while we typically assume linearity in the relationships, when the changes in the exchange rates are sufficiently large, that might not be a tenable approach. In particular, the share of manufacturing, and the share of plausibly tradable goods, has been declining over time.

Figure 5: Manufacturing value added to GDP ratio (blue) and tradable sector value added to GDP ratio (red). Source: BEA industry statistics and author’s calculations; for details of calculations, see this post.

Hence, so far there’s been a substantial response of trade flows to lagged exchange rate depreciation — although not in my particularly surprising given what we know from the econometrics. Whether the magnitude of the response will be smaller due to the shrinkage of the tradable sector over the years of the housing boom, along with adjustment costs associated with moving factors of production across sectors, or whether it will be larger, due to the increased tradability of services induced by the adoption of new information and communications technologies, remains to be seen. So it might be that subsequent dollar declines might not induce the same degree of trade adjustment.

And of course, the largest determinant of export demand remains rest-of-world GDP growth (remember, the contribution of exports to GDP growth in 2007Q4 was about equal to that coming from the decline in imports [2]). Continued export growth relies upon continued rest-of-world growth.

Technorati Tags: trade deficit,

imports,

exports, pass through,

dollar,

euro, expenditure switching,

Krugman,

monetary policy,

foreign exchange intervention.

I’m very curious as to where this export growth is supposed to come from. Certainly the US is a net exporter of aircraft, weapons, software, and entertainment. But our erstwhile lead export industries, like chemicals and agriculture, are no longer. Dow Chemical is even threatening to leave on the claim that there’s not enough natural gas to fit their needs. But outside of the BMW decision to expand in SC, I haven’t heard of any plans to build capacity in the US for a long time.

You don’t change your net trade position without either cutting imports or building manufacturing capacity.

well maybe i shouldn’t be as concerned about a repeat of the bank of england in ’92 as i have been.

seeing the wind come die down in the crude and commodity markets yesterday calmed me down a bit.

I haven’t heard of any plans to build capacity in the US for a long time.

You’re kidding, right? Kia’s building a plant in Georgia as we speak. VW and Audi are both in the early stages of building plants. Honda is staffing up a plant in southern Indiana. Their Alabama plant has been open for a year or two and cranked out 300k vehicles last year.

These “transplants”, as Detroit calls them, are booming.

As for the dollar falling… I think there is no bound on how low the dollar can go. Recall, that the European Bank is currently battling inflation so they would be inclined to increase interest rates not decrease them. Hence with higher interest rates, if I were John Q Investor, then I get a higher return on my money in Europe than in the US. Furthermore, as the Fed lowers our interest rates the difference between the rates is the point of interest at the moment. If the Fed keeps lowering rates at Wall streets request and the European Bank increases rates then a cycle could form that may be problematic for the US.

Professor Krugman’s piece shows that he is still as unaware of a critical issue as he was when authoring the paper “Will there be a dollar crisis?”

http://www.economic-policy.org/abstract.asp?vid=22&iid=51&date=July+2007&aid=183

Namely, that the pain caused by a fall depends on how high you were before falling. Specifically, the US dollar is (still) in a unique position as the main international trade and reserve currency, and it is precisely that use which props its value. If it were to become just another currency in a world of peers (along with the Canadian dollar, the Brazilian Real, etc.), its value would be much, much lower than todays, and the impact of the transition on US life would be staggering.

An even more serious side of this issue is that, if the US are intent on debasing the dollar, they probably will also follow (or keep following) a strategy that will soften the pain for them but have a dramatic impact on the global poor: turning an ever greater share of US corn to ethanol (and then soybeans to biodiesel) will cause in a few years the halving of US agricultural exports in volume and their doubling at least in dollars (i.e. at least quadrupling agricultural prices). That will substantially reduce the US current account deficit and avoid the much deeper plunge in the dollar value that would otherwise occur.

The US has certainly the right to follow that path. But they also have the duty to tell the world openly that they will do it. Like: Along the coming years and decades our food exports will become progressively lower in volume, and the same will probably happen to total world food production. It is conceivable that they could be half their current volume in 10 years. People, and particularly poor people, should have it in mind when making procreation decisions.

Dropping a nuke on a city is not genocide if its dwellers are given a week’s notice.

The rest of the post just explains the point in the first paragrapth.

Within a fair and logical conceptual framework in which all national currencies are peers on an equal standing, the intrinsic value of any national fiat currency outside the issuing country arises exclusively from the possibility of using it for purchasing goods, services and property rights FROM THAT ISSUING COUNTRY in a reasonable timeframe.

Thus, the relative intrinsic value of the US dollar versus the Brazilian real and the Russian rouble comes exclusively from the possibility of using the mass of dollars outside the US for buying something from the US versus the possibility of using the mass of reals outside Brazil for buying something from Brazil and the mass of roubles outside Russia for buying something from Russia. And this is enough to tell us that todays valuation of the dollar has nothing to do with its relative intrinsic value, because, while it would take a very long time to use the enormous mass of dollars (and of dollar-denominated debt) floating outside the US to buy real things from the US at their current prices in dollars, there are simply no reals outside Brazil and no roubles outside Russia.

Therefore, the relative value of the dollar today is far higher than its intrinsic value, and it depends on economic actors worldwide accepting (outside of any fairness and logic) that it is valid tender for goods, services and property rights FROM ANY COUNTRY, not just the issuing one.

Now, money is a social psychological construction: it is within the minds of the members of a society (be it the world or a concentration camp) where a specific entity becomes a currency, where the main factors that prompt those members to reach such a consensus are the perceived intrinsic usefulness and scarcity of the entity (along with its durability). Thus, gold and silver were real money worldwide for many centuries, cigarettes were real money in concentration camps, and dollars as valued today are real money wordlwide.

In exactly the same way, it is within the minds of the members of a society that an entity can cease being a currency. Thus, just as, after being freed from the concentration camp, non-smoking former interns stopped accepting cigarettes in exchange for anything, so it is entirely plausible that in the very near future – prompted by the perception that the Feds chosen monetary path is making the dollar less and less scarce – economic actors worldwide reach a new consensus whereby they agree to assign the dollar just its intrinsic fiat value. And that intrinsic value is far, far lower than todays.

Buzzcut says, “Kia’s building a plant in Georgia as we speak. VW and Audi are both in the early stages of building plants. Honda is staffing up a plant in southern Indiana.”

Thanks for the information.

However, this does not constitute a manufacturing boom. KIA is 2900 employees, VW will be 1,000-2,000 *if* it goes ahead, Audi is still thinking about it, Honda is 2,000.

If Dow offshores, that would offset this many times over.

So I still don’t understand where the export growth is coming from.

Companies like Emerson Electric(EMR, just so as not to confuse it with the manufacturer of radios and TVs) and Illinois Tool Works have significant growth in their sales overseas. Foreign industrial growth and growth in their electric utilities have boosted things like sales of machine tools and generators. For example, exports of nuclear reactors, boilers, and the like(category HS-84 on the trade tables) have increased from $130 billion in 2002 to nearly $200 billion in 2007. The overall balance deteriorated over the period except in the 2006-2007 period which is in keeping with overall trade figures. Not all the growth in exports is simply in the areas we have surpluses. There has been a narrowing of the deficits in other sectors aided by the competitive advantage of a weaker dollar.