How shall we describe what happened this weekend with Bear Stearns? The first big casualty of the credit crisis, yes. Bailout, no.

Bear Stearns was an investment bank that made trades and created markets for a broad range of securities, including extensive use of derivative contracts such as credit default swaps. In a credit default swap, the seller agrees for a fee to absorb the losses if a certain asset specified by the buyer goes into default. As an upper bound on the importance of such positions, one can look at the gross notional value of all derivative contracts. For example, if you’ve sold a put option under which somebody could force you to buy 1000 shares of IBM at $100 a share if the price falls that low, your notional exposure would be $100,000. According to Bear Stearns 2007 10-K, the notional value of all Bear’s derivative contracts as of November 2007 came to $13.40 trillion. That’s trillion, with a “t”. As in, about the same number as total 2007 U.S. GDP. Now, Bear’s actual net liabilities could under no conceivable scenario actually achieve that number– for example, if that put is exercised, and you sell at $95 the shares you’re forced to buy at $100, you’re actually only out $5,000. But $13.4 trillion is a staggeringly big number, whatever it means.

|

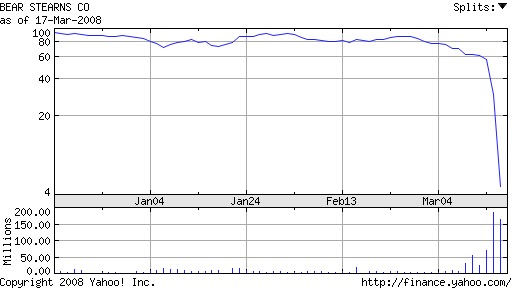

A second number that I find fascinating is Bear’s stock price, which had fallen from $100 a share at the start of this year to $30 on Friday. Under the deal brokered by the Federal Reserve over the weekend, JPMorgan offered to take over Bear for $2 a share, or less than $300 million for the entire company. By comparison, Bears’ NYC building alone is thought to be worth $1.5 billion. Hence when I read statements like this one from Elizabeth Spiers it drives me nuts:

Now Bear is being bailed out by the Fed via JPMorgan Chase, which is buying the troubled firm for $2 a share…. The Fed itself is dodging criticism from people who worry that its willingness to play lender of last resort to the embattled brokerage will cause similar institutions to expect that their worst mistakes can be fixed with a Fed bailout.

$2 a share is a “bailout” that “fixes” management’s worst mistakes? I rather think instead that it pretty much wipes out the stake held by owners of the company, and is the very least that could possibly be offered as inducement to try to get Bear to agree to the steps necessary to swiftly resolve the huge problems that its illiquidity creates.

No, $2 a share is no bailout, but instead represents a fire sale price. Indeed, as Felix Salmon observes $2 seems to be substantially below that minimum necessary inducement. BSC shares are trading at the moment closer to $6, suggesting owners have reason to expect something better can be obtained than the initial proposal.

True, the Fed did offer a $30 billion non-recourse loan to JPMorgan to sweeten the deal. But what twist of logic would lead us to describe that as a “bailout” of Bear as opposed to an inducement to JPMorgan to help clean up the mess?

Granted, this and the Fed’s other recent unconventional measures are exposing the Fed– and ultimately the U.S. taxpayer– to additional risk. But knzn offers a good counterpoint– perhaps the greatest single risk to the U.S. Treasury is the risk of declining tax revenues from a major economic downturn. I do not share knzn’s particular fears of deflation in the U.S.– I am absolutely confident that Bernanke can and will prevent deflation. But lost revenues from an economic downturn are already a reality, and it’s only a question of how much more severe that’s going to become. Minimizing net loss to the Treasury, receipts and expenditures included, is perhaps one reasonable metric for deciding how big a risk it makes sense for the Fed to assume in this situation.

But I think the really troubling thing about this development is the rapidity with which Bear’s capital seems to have disappeared in smoke. It looks to me like the correct language to describe what happened is that of a classic bank run— Bear’s short term creditors said “no mas”, and it was impossible to liquidate long-term assets fast enough to cover the gap.

Some are saying that this was ultimately an error by the Fed, in failing to provide interim liquidity to Bear sufficiently quickly. But that we have been marching toward a day like last Friday should have been very clear to everyone for at least a year now. Stability of the system is supposed to be achieved by ensuring that any institution that is borrowing short and lending long holds a sufficient cushion of net equity so as to be able to absorb the losses from short-term liquidation. Whatever the true meaning of the $13.4 trillion notional exposure, that number was “only” $8.74 trillion in 2006. It appears that Bear was unable or unwilling to work itself into a position of lower leverage and higher equity even with one year’s advance warning. For which, I say, the owners and managers should and will suffer.

Bear is not going to be last, but it is the model I think for what we’d want to see– owners of the companies absorb as much of the loss as possible, while the Fed does its best to minimize collateral damage.

But if you’re still walking the streets of New York, watch out for falling debris.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

economics,

Federal Reserve,

Bear Stearns,

credit crunch

Bear is not going to be last, but it is the model I think for what we’d want to see– owners of the companies absorb as much of the loss as possible, while the Fed does its best to minimize collateral damage.

But the owners are not absorbing any of the real loss. They are only absorbing the loss of their phantom paper equity, their stock price. It turns out that their wasn’t any real equity there at all. Their underlying assets were negative, which was exposed by the price that JP Morgan paid.

The real bailout is for the bond investors who the Fed is backing with a $30 billion non-recourse loan. Is the moral hazard any less that we bail out incompetent bond investors rather than bail out incompetent Bear Stearns executives? Why not bail out home owners?

It was a bailout – not of the shareholders or the employees, but of the banks. The purpose was to avoid a test of the counterparty risk in CDSs. BSC could have been the beginning of the chain reaction.

After looking at BSC’s “book” JPM decided that it would need a (potential) 30 billion dollar taxpayer money “kick-in” in order to make the $2 per share offer.

Now 30 billion dollars represents $254 per BSC share.

So JPM considers the maximum safe use of ITS capital to be $2 per share – $254 per share = -$252 per share.

That is what it has “roughed out” as the per share “enterprise value” of BSC as of the close on Friday, 14March2008, -$252 per BSC share.

Is JPM correct on that estimation or did they just get the deal of the century?

That is the question that interests me, and the markets seem to think that it may just have worked a steal,

but the markets have not seen the BSC book and JPM has.

i love your analyses, but to not consider this a bailout is myopic. that collateral for those “non-recourse” repos is bear garbage in name alone — in reality, it’s everybody’s garbage, or was, because now it’s ours (the public).

the government talks in laissez-fairese when it’s a question of not buying up distressed assets in the form of residential mortgages — then turns around and publicly finances the capital losses on derivatives tied to those assets.

wasn’t it henry ford who said there’d be blood in the streets if people could figure out what the fed actually did?

I have a copy of JPM’s presentation to investors. JPM indicates that they are going to incur $6b in severance, transition, and legal costs with the acquisition.

It seems to me that the price JPM is paying is higher than the stated $2. One also needs to ask whether anyone would be willing to buy BSC without the $30 billion in guarantees that the Fed is offering.

As for the $13 trillion notional amount, it points out that there is too much concentration of financial wealth in just a few firms.

$270 million, or whatever, is a “notional” amount. JPM shareholders seem to think otherwise, since they’ve run JPM market cap up about $15 billion yesterday and today.

I think what many people seem to be missing is that this is a $30B bailout of the shadow banking system.

Yes, the most obvious part is a $2/share equity offer from JP Morgan. Yes, the immediate cause was repos.

But the root cause was the huge number of credit default swaps and other private derivative agreements Bear had entered into. No one, not Bear’s counterparties, and not Bear itself had or has a good idea of the extent of the risk of those contracts. No one can even come up with a ballpark number (hence, throwing around huge notional values, but as you say, this is not meaningful).

So JP Morgan punted. We can’t value it. But best guess is that we won’t lose more than $30B. So, provide us with a $30B money back guarantee and we buy Bear for virtually nothing (i.e., take on the risks of the contracts).

As long as the US Government is implicitly backing the counterparty risk in CDS’s, the banks will continue to gamble excessively in the shadow banking system. This moral hazard needs to stop. Banks need to be shown that if they leverage too highly with derivatives, or take on too much poorly understood counterparty risk, that they will explode. Mommy and Daddy will not save them.

I think the real message sent by the Bear bailout is that gambling with derivatives is fine, just don’t invest in the stock of your own bank. Instead, receive your bonus as a bunch of stock options each year, gamble with derivatives to temporarily juice the returns on your stock (and thus make your options worth a lot more), and when you finally threaten to explode, the government will bail you out for all your derivative exposure, and although your stock tanked, you didn’t own any. Good thing you exercised all your options (and sold the stock) each year!

Erik R:

What you seem to be saying is that Bernanke and crew have decided to encourage the actual expansion of the CDS bubble rather that the deleveraging that is underway.

WOW.

Since Bernanke is far and away the wildest exponent of loose money in my lifetime, you may just be right.

And if so, Federal Government of the United States of America will soon become the Super SIV that the private sector concluded was an insane fantasy.

If the choice is between bankruptcy or a $2 sale, BSC shareholders are far better off taking the $2 per share. Bear Stearns was so heavily leveraged any liquidation of assets, particularly now of all times, would have likely resulted in non-meaningful recovery for creditors, much less shareholders.

The real sweet spot for JP is that, if I understand correctly, the Federal Reserve has agreed to guarantee 30B of Bear Stearns worst assets. Given that, maybe $2 is too low, but I don’t see many other counter-bids stepping up to the plate.

From my limited perspective, I agree that BSC cannot be construed as a bailout, but that the sale was in everyones best interest given bankruptcy was the only other alternative. I think the real interesting part of this story is the dramatic expansion of the Federal Reserves power, which now seems to be extending finances to institutions it has zero control over.

$13.4-trillion in derivatives notional value?

What a bunch of wussies.

JPM has notional exposure of $91.7-trillion as of 2007-9-30 (Table 1, page 21 of pdf; there are other figures in the table, which have different source documents).

Note that about 2/3 of that is interest-rate swaps, in which the volatility is a little less scary because there’s netting implied in the contract (pay floating, get fixed on notional amount, or vice versa).

I’m not sure how much of the BSC problem was derivatives exposure and how much was the stress of constantly having to finance their mortgage portfolio. I’ll guess the latter, but won’t argue much with the former.

There’s some moral hazard (and justification of the term “bail-out”) introduced by the fact that the bondholders will emerge not just unscathed, but with better credit quality if the deal goes through. But there’s no way of getting them to feel the pain short of bankruptcy.

My guess is that the JPM deal is a stalking horse … JPM is getting a break fee in exchange for backstopping an auction. The non-recourse Fed sweetener is the Fed’s way of making sure it likes the winner.

And the part I find absolutely fascinating – and reminiscent of some CDS/Bond games reported, which arise from the separation of economic incentive and voting rights – is the idea that bondholders are buying stock at $6 in order to tender at $2 but get their bonds / CDS portfolios looking much nicer.

If the purpose of banks is to provide a counterparty for transactions but are usually reliant on the government anyway whenever things go south, shouldn’t the government just take over the function of settling transactions?

Todd Boyle said: A bank is just a general ledger, with security, and a 19th century interface. Clerks who stand all day behind counters, rubberstamping things. Check it out: http://ledgerism.net/journalbus.htm

chul: good point.

Kevin A above noted that the fed is now extending credit to unregulated entities; i’d like to see the authority for that in their mandate.

one way forward would be that, in exchange for all this national liquidity, the fed reserves the right to mark outstanding MBS junk to market.

Jim – Maybe it’s my dyslexia, but you have me confused. You write, “if you’ve sold a put option under which somebody could force you to buy 1000 shares of IBM at $100 a share if the price falls that low, your notional exposure would be $100,000. ….. for example, if that put is exercised, you buy at $95 to fulfill your obligation to sell at $100 so you’re actually only out $5,000.”

Wait a minute. If I buy at $95 and sell at $100, don’t I make $5 per share or $5000, not lose it. Anyway, the way you define the put, it forces me to buy at $100 not sell. So the shares cost me $100,000 and I can only sell them for $95 per share or $95,000, thereby losing the $5,000.

Sheesh, of course you’re right, Carl. I’ll fix that.

March 18, 2008

Price & Value! They’re not always the same thing – which is wonderful for those of us who achieve outperformance by exploiting the difference – but sometimes they get so far out of whack that real pain is experienced. We’re going to b…

JDH,

I urge you to listen to the Goldman and Lehman conference calls from today. Both firms stated, explicitly, that they viewed the new non-bank Fed financing as a “revenue opportunity”, a “viable source of financing for our customers.”

Is it a bail out of Wall Street when emergency funding is viewed as a means to increase already-healthy profits?

And by the way, obviously the shareholders of Bear Stearns were shafted, just as the creditors of the firms were unquestionably bailed out. Ask and CDS holder, repo provider or subordinated debt holder of Bear if they feel “bailed out”.

“True, the Fed did offer a $30 billion non-recourse loan to JPMorgan to sweeten the deal. But what twist of logic would lead us to describe that as a “bailout” of Bear as opposed to an inducement to JPMorgan to help clean up the mess?”

In the world of microeconomics, at least, the formal placement of a tax or subsidy is irrelevant to its ultimate incidence. Whether a sweetener was offered to Bear, or a sweetener was offered to Bear’s buyer, shouldn’t make a damn bit of difference to the ultimate question of who pays and who gains.

David Pearson, just out of curiosity, how were stockholders getting the “shaft” here? BSC was running on its last limbs and almost certainly would have declared bankruptcy had it not been for an intervention. Given that shareholders would have gotten nothing after liquidation, and creditors less than their investment but more than nothing, everyone benefits by avoiding bankruptcy.

Certainly, creditors benefit the most. But $2 is still more than $0. Pareto optimality, right! This is far superior to liquidation.

Kevin A,

You’re right: $2 is better than nothing. But my broader point is that the “bail out” of creditors here is obvious.

Look, Bear, as an institution, had leverage second only to the likes of LTCM. The providers of that leverage made a bet on liquidity being abundant. They were on the verge of losing that bet when the Fed stepped in to bail them out. The message to creditors is clear: go ahead and lend to highly levered institutions; the Fed will bail you out if something goes wrong.

It’s a bailout of the debtholders. It’s taking on a 30B liability. Are you clueless?

The Fed had a real motive to rescue Bear. Bear was a primary dealer. As such, it dealt directly with the Fed and was an important cog in the implementation of Fed policy, and the functioning of its money supply machinery. E-trade will not be rescued by the Fed.

Primary dealers defined:

Primary dealers are banks and securities broker-dealers that trade in U.S. Government securities with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. On behalf of the Federal Reserve System, the New York Fed’s Open Market Desk engages in the trades in order to implement monetary policy. The purchase of Government securities in the secondary market by the Open Market Desk adds reserves to the banking system; the sale of securities drains reserves.

The primary dealer system was established by the New York Fed in 1960 and began with 18 primary dealers. In 1988, the number of dealers grew to a peak of 46. From the mid 1990s to 2007, it declined to 20. The most important reason for the decreasing number of dealers is consolidation, as Government securities trading firms have merged or refocused their core lines of business.

List of the Primary Government Securities Dealers as of 11/30/07:

BNP Paribas Securities Corp.

Banc of America Securities LLC

Barclays Capital Inc.

Bear, Stearns & Co.

Cantor Fitzgerald & Co.

Citigroup Global Markets Inc.

Countrywide Securities Corporation

Credit Suisse Securities (USA) LLC

Daiwa Securities America Inc.

Deutsche Bank Securities Inc.

Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein Securities LLC.

Goldman, Sachs & Co.

Greenwich Capital Markets, Inc.

HSBC Securities (USA) Inc.

J. P. Morgan Securities Inc.

Lehman Brothers Inc.

Merrill Lynch Government Securities Inc.

Mizuho Securities USA Inc.

Morgan Stanley & Co. Incorporated

UBS Securities LLC.

======================================

If Bear had collapsed, sorting out that mountain of 13.4T$ of contracts would have been a nightmare. The Fed would have been paralyzed in implementing monetary policy while the damage was being sorted out. It was not a risk that the Fed wanted to take. If Charles Schwab goes under that will be Chuck’s problem. The Fed will not be involved, unless his name is on that list.

===========================

The following is from the Fed press release announcing the March 16 moves to deal with the crisis:

First, the Federal Reserve Board voted unanimously to authorize the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to create a lending facility to improve the ability of primary dealers to provide financing to participants in securitization markets. This facility will be available for business on Monday, March 17. It will be in place for at least six months and may be extended as conditions warrant. Credit extended to primary dealers under this facility may be collateralized by a broad range of investment-grade debt securities. …

Emphasis added. See: Its all about the primary dealers.

The Fed will not bail out your ner-do-well uncle Moe, who financed three houses with liar’s loans, no money down, and a smile. Moe spent all last summer explaining how he was going to make a fortune after he slapped a fresh coat of latex on them and flipped them this April. And you, you ingrate, didn’t have the heart to tell him that latex will not stick to oil paint.

What if you turn the question around a bit.

Is it a bailout of JP Morgan?

esr,

JPM guaranteed all BSC positions and took the risks of derivatives. Fed loaned 30B with COLLATERALs. While these collaterals may be illiquid MBSs, they certainly are not derivatives/CDS.

TCO:I t is the firm’s owners and managers, not its creditors, that make the decisions of what the firm does.

mortfin: I don’t understand your analogy. If creditors want to lend but the firm goes out of business if it borrows, why is that the same incentive structure as providing a capital injection so that the firm can continue? And I don’t understand how you can survey the situation at the moment and conclude that the #1 problem is an excessive willingness to lend to firms like Bear.

Fatman: You have it exactly backwards. These firms are dealers because they are important to the financial system, not important to the Fed because they are dealers.

JDH wrote:

“It is the firm’s owners and managers, not its creditors, that make the decisions of what the firm does.”

So why didn’t Bear’s owners and managers decide not to go bankrupt over the weekend? Why did they need the Fed’s help?

I’d say that during the last week, the creditors decided, as a market, to bankrupt Bear, but the Fed decided against bankruptcy. I don’t see as the owners had much of a say in the matter at this late date (although they certainly made decisions over a longer time frame that created the problem)

ErikR, it’s precisely the incentive structure for those longer time frame decisions that I believe is the issue here.

JDH:

That is only part of the issue. Certainly a message is being sent that owners (shareholders) will receive little, if any, help from the Fed.

But simultaneously, a very strong message is being sent that the creditors will saved. Now everyone knows that the failure of certain corporations strikes fear into the hearts of the Fed governors, and therefore the Fed will not allow the possibility of default for these corporations.

The incentives to investors are clear: favor lending to Fed-protected institutions over unprotected ones. Favor investing in bonds and non-exchange-traded derivative contracts over stock.

Although I don’t like it, I’m not too worried about the first incentive. But the latter incentive worries me a great deal.

Funny how economists spend so much time writing about how the free-market is a better way to run a system than government control. And when the rubber hits the road they do the opposite of what they say.

Suggestion: we all agree to correct anyone using the phrase “$30 billion bailout.”

– The FRB did not spend $30B, it loaned it (with interest.)

– The FRB received extensive collateral on the loan. According to press reports, they obtained loan covenants to protect the value of these instruments (although I’ve yet to read details.)

– While the market value of this collateral is well below the notional value of the loan (but still a considerable fraction), the market value incorporates a considerable liquidity discount. The Fed (and the government) faces no such liquidity squeeze, and so values these assets at a premium to the market. Transfer of such assets to the Fed is Pareto-improving.

– The Fed faces a further gain in accepting illiquid assets as collateral as doing so provides a public good: liquidity to the banking system. This reduces the net cost (or increases the net profit) to the public further still.

– Finally, the loan was not provided to BSC, so anyone who suggests that is the value of aid provided to BSC gets rapped on the knuckles twice.

The Bear Stearns New york building is thought to be worth $1.5 billion. Did they have a subprime mortgage on it?

SvN:

So, how big a bailout is it, if not $30B?

Or do you claim it is 100% certain the loan will be repaid in full?

I think it was a bailout. As I said in a letter that I’ve submitted to the WSJ, the bailout took the form of the Feds assistance to J.P. Morgan. Relatively little is known about the terms of this assistance, but an indication of its value can be gleaned from J.P. Morgans stock price.

On Monday, following the weekend deal announcement, J.P. Morgans stock price shot up 10%, resulting in a $12.8 billion increase in its market capitalization. Since the shares of other money center banks fell Monday, this increase must largely reflectand indeed, may understatethe value of the Bear Stearns acquisition to J.P. Morgans shareholders. This $12.8 billion figure works out to a gain of $108.50 per share of Bear Stearns stock, and together with the $2 acquisition price, implies a total valuation to J.P. Morgans shareholders of $110.50 per Bear Stearns share.

Bear Stearns shares last traded as high as $110 in early August, before the turmoil that has since gripped U.S. credit markets. It is virtually inconceivable that in the current environment Bear Stearns shares would be worth anything close to this amount without a substantial injection of value from the Fed. Even the assumption that the company was worth $70 per shareBear Stearns stock price before the onset of its collapseimplies a Fed subsidy to J.P. Morgans shareholders of over $4 billion. Quite likely the subsidy was much larger than that.

It is difficult not to conclude that the Fed panicked, there was no plan B, and J.P. Morgan took full advantage of the situation. It reinforces the impression that the Fed has been chronically behind the curve and almost certainly remains so even as it now assumes a virtually unlimited role in U.S. financial markets. The Feds actions do not inspire confidence in it or in a happy ending to the current financial crisis.

It’s bail out for all investment banks and their less-than-honest assessment of the value of their portfolios. The Fed by intervening the bankruptcy of BSC in effect put a floor on the price of these assets from their equilibrium point. The next bailing policy, I am almost certain, the Feds will pursue is to internalize bad mortgages. Another bailout is coming, count on it.

Bottom line, Bear didn’t have a choice. JPM and other banks carefully orchestrated Bear’s margin calls and subsequent fall. The Fed, being very much in-bed with JPM, handed the fallen Bear to them for pennies on the dollar.

This was a classic case of the JPM using its relationship with the Fed to crush Bear so that it could buy it. The Fed, acting in lock-step with JPM wishes, not only gave Bear to JPM, but gave JPM protection, using our tax dollars, from loss.

Never ever bet against JP Morgan. This deal will go through. If by some miracle it doesn’t, JPM can buy 20% of Bear stock at $2 per share and it can also buy their NYC headquarters for roughly 30% less than it’s worth. No matter what, JPM comes out ahead, thanks to the Fed and our tax dollars.

No, this wasn’t a bail-out, it was an orchestrated robbery of the American taxpayer, and a slaughter of Bear employees.

Jim says that what happened looks like a classical bank run, and ErikR used the phrase “shadow banking system” — I think you both are exactly right on this key issue of the current financial crisis. Basically, we are experiencing a bank run outside the banking system and we don’t have the institutional arrangement to stop it. It was a classical bank run with the ABCP market: we have long-term assets (houses) backed by short term financing: commecial paper. It was a classical bank run with the municipal bond market: long-term projects such as hospitals are backed by these tender option bonds, which are basically short-term funds. More generally, the entire MBS market has this maturity mismatch of assets and means of financing. So it feels like we are back to the days of early 20th century: how do we stop a wide spread bank run before the existence of FDIC? The fed is trying, but …

Bear Stearns Bailout: It’s Not Who You Think

The quick read from the press is that the purchase of Bear Stearns by JPMorgan Chase was a bailout. Jim Hamilton over at EconBrowser doesn’t buy that story. He says, $2 a share is no bailout, but instead represents a

30 billion dollar loan that no sane private sector lender would have/could have given JPM? Sounds like a taxpayer financed bailout of Wall Street to me. The fed is loaning massive sums of money at below market rates on dodgy collateral. If not a bailout it’s at least a massive subsidy to Wall Street

Do Not Listen to Cramer… Ever.

See Also: Von Hoffmann Award Nominee, $2 per share is not a “bailout.” It’s a fire sale., What These Market Conditions Could Mean For You The Individual., Evening Thread: The Economy, An Example of Bear Sterns’s Conduct?, Ins…

“These firms are dealers because they are important to the financial system, not important to the Fed because they are dealers.”

I mostly quoted the Fed on this subject. I note that in order to be on the list of Primary Dealers, a firm must apply to the Fed for that listing, and must meet standards for capitalization and regulatory status.2

As noted above the number of primary dealers has changed overtime, ranging from 18 in the beginning almost 50 years ago to a high of 46 to the current number of 18 (with the collapse of Countrywide and Bear, during the last few months).

Of that 18 only 5 are broker dealers that are not part of a domestic or foreign BHC: Cantor Fitzgerald, Goldman, Lehman, Merrill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley. The 3 largest domestic BHCs

(BA, Citi, and JPM) are on the list, but number 4 Wachovia, which has a B/D subsidary, is not on the list.

The other 10 operations are foreign owned — 3 British, 2 Swiss, 2 German, 2 Japanese, and 1 French.

As for which came first, logically it is the Fed, which organized and regulates the system. Factually, it may not be that neat. But then chickens and eggs have a curious relationship.

It strikes me that the fundamental problem with the Bear Sterns situation and for many of these recently introduced investment vehicles is leverage. By using so much leverage, they are playing with explosives that may blow up in their faces at any moment and all the Fed has done is rush in and defuse one of these financial bombs right before it was about to go off, potentially starting a chain reaction with JP Morgan and all the other financial bombardiers going off in turn, and slapped Bear on the wrist by selling their shares for $2. JDH looks at the wrist-slapping and says it’s not a bailout, I and others believe that this intervention invites more future risk-taking. If the government and the Fed really believe that these explosives are so dangerous, regulate them and stop people from using them. If not, let people blow some fingers and arms off and learn from their mistakes.

Of course, the standard counter-argument given is that innocent bystanders will be killed and there will be collateral damage. I say you cannot avoid collateral damage by letting dimwit bankers juggle live investment grenades in crowded subways while the Fed constantly steps in right before a Bear or LTCM is about to go off. Either regulate them below certain levels of leverage or away from certain protected investments like mortgages. or let them blow limbs off and kill civilians, allowing the markets to learn in the process. Continuing to let them lay elaborate webs of land mines while the Fed steps in only when idiot financiers are right about to step on and trigger one of their own mines is an invitation to a much larger future disaster. As a libertarian and with no skin in the game, I would rather let the bombs go off and let people and the markets learn from the ensuing carnage.

So, is it a bailout at $10 a share?

Well, you can say it’s not a bailout if you want to, but this sounds a lot like “I don’t want it to be called a bailout, so I’ll just call it something else”. Fact is that had our taxpayers money not been used (bailout), there would have been no reason for JPMorgan to even offer $2 per share. Without taxpayer money, the shares would have been worth $0 each. On top of that, CEO Cayne would not have got the $61 million from his stock without taxpayer money (bailout). Therefore, you can call it by any name you wish, but a bailout is a bailout.