The Federal Open Market Committee’s next meeting is scheduled for April 29/30, which the May fed funds futures contract currently anticipates will result in another 25-basis-point reduction in the target fed funds rate down to 2.0%. Here’s why I hope the Fed doesn’t do that.

|

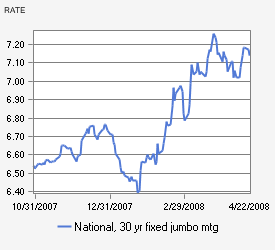

No matter how dire your outlook for the real economy may be, the first question that must be asked is, How much benefit could another 1/4-point cut provide? For home purchases, for example, the expected change in house prices and income over the next 12 months is likely to be a more important factor than the interest rate in the current environment. And even if the interest rate were the most important variable, it’s not clear how much a 1/4-point reduction in the fed funds rate would actually matter for the cost of borrowing. For example, over the last six months, the Fed has cut the target by 250 basis points, while the cost of a 30-year jumbo mortgage rose 60 basis points. That’s if you can still get the jumbo loan, which you may well not.

By contrast, there is a compelling case that by rapidly bringing the yield on short-term Treasury bills well below the prevailing inflation rate, the Fed has played a role in the significant depreciation of the dollar and increase in the dollar price of virtually every storable commodity that we’ve seen since the beginning of January. A USA Today/Gallup survey this week found that 80% of Americans are worried about rising gasoline prices and 73% about rising food prices, with about half of respondents claiming that these price increases had created hardships for them. Would lurching further down that road really stimulate consumer spending?

Markets are assuming that Bernanke will go to 2.0, and that expectation is built into the current price of storable commodities and the dollar. If the Fed instead surprises the market with a little restraint next week, I predict that we’d see immediate adjustments in those prices.

In part those effects would result from changing the fundamentals, surprising speculators with a higher real interest rate and firmer inflation-fighting commitment from the Fed than the market is currently assuming. But it’s possible in my mind that there also is a psychological component to the current commodity speculation as well, in which case the Fed has a rare opportunity right now to get some extra benefits on the inflation front by breaking that psychology. However, if the Fed waits and lets the present perceptions become more entrenched, that same psychology could turn out to be a factor that later proves to work against the Fed and make anything it tries to do more difficult.

The Fed’s credibility as an institution that will not tolerate a resurgence of inflation is absolutely critical for its ability to achieve its dual mandate. If the Fed loses that credibility, monetary expansion brings inflation but little output improvement, and monetary contraction brings a recession but little relief on inflation. When consumers report in the latest Michigan/Reuters survey that they expect 4.8% inflation over the next year, the Fed has a real problem in that department. If the Fed waits to pause until the June 24/25 meeting, it may find itself swimming against that credibility current for many years to come. I believe that the Fed has a unique opportunity to signal its true commitment at next week’s meeting that may not come again any time soon.

Furthermore, if I am reading this correctly, we will not have to wait around to ponder what the outcome means. If the Fed surprises the market with a pause, we should have unambiguous confirmation or refutation of the hypothesis that the Fed has been contributing to the commodity price run-up within 48 hours of the FOMC’s announcement. That knowledge in itself would also be extremely valuable– valuable to the Fed in calculating how to chart its course from here, and valuable in terms of making clear to the public why sometimes higher interest rates are the better choice for public policy.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

economics,

Federal Reserve,

interest rates,

credit crunch,

Bernanke,

inflation

The Fed will lower rates, because $120 oil is just a side effect of putting a nominal floor under house prices sooner than we’d get with a sound dollar.

They will risk inflation to counteract a deflation/liqudity trap.

If $120 oil bothered them, they could’ve already reacted and raised rates .25 to make their point clear, particularly when it probably also would’ve had no impact on actual lending rates. The silence speaks volumes.

If we’re lucky, we’ll only have a 1970s experience.

I, for one, will be greatly surprised if Ben surprises the markets on the downside. To my mind, the fed has consistently demonstrated willful ignorance on inflation – from the focus on ‘core inflation,’ to the published forecast of $70 per barrel oil. Its policies seem to be run on the basis of short-term popularity. I think we are in a lull now; the storm is not over, it is gathering strength. Ben is much more afraid of a downturn than he is of inflation.

There were two dissenters last time, maybe that indicates there’s a reasonable chance of the Fed staying put.

Clear and logical, Professor.

I say that if he displays continued pigheadedness next week, that you professorial types vote him out of the AEA.

It would be a nice tactical move, but the fact is they have to be prepared for the possibility of the worst case for housing, however remote, which would means an eventual 0 funds rate. So they can stay put next week, but they won’t be able to say its necessarily the end. They’d effectively have to lie in the statement in order to get a sustained dollar reaction. But they’re not in a position to call the end because they simply don’t know. I’m guessing Bernanke will insist on intellectual honesty in the statement. The dollar may revert back to weakness after a week or so.

When you say “The Fed’s credibility as an institution…” and

“If the Fed loses that credibility…” you are joking, right? The Fed lost its credibility when it bailed out Bear Stearns and allowed the banks to borrow government gobs of money at below market rates.

For JH, a very real question here is whether the Fed drove the TBill rate down or just reacted to the market’s rush to TBills away from other short term instruments. The spiking of the spread between TBills and CPR that occured in the fall/winter was not a Fed-induced event. However, there is a point where concerns about the liquidity crisis may have to yield to concerns about inflation.

For commentators, “bailout” of Bear Stearns? Facilitating the liquidation of a company at 1/10 is value from 2 weeks earlier and 1/20 its value from a year earlier is hardly a bailout. If you were a BS shareholder, I doubt you would feel bailed-out.

For the Fed/Bernanke bashers, do you really have no concept of what a financial meltdown would do and why avoiding is critical? Read William Poole’s article in STL Fed Review last month. The Fed bashing is a bit like a guy complaining about someone breaking into his house who just diffused a nuclear bomb.

Three month libor is 2.91%, the last TAF auction stopped at 2.87%, and this with expectation of 2% fed funds next week. The financial system is still under incredible duress, and not cutting next week most certainly won’t bring down mortgage rates. I suspect the current optimism about recovery of the financial system will prove extremely premature and short-lived.

The $120 oil isn’t the problem.

The food riots that result from rising fertilizer prices and commodities speculation are.

The credibility at issue here is not affected by the Bear Stearns deal. Bear Stearns is a moral hazard issue. The issue at hand is inflation. Those who think the Fed’s inflation fighting credibility is already lost were probably not around in the 1970s need a trip to the library. This is nothing, kids.

Fed funds futures are overwhelmingly pointing to a 25 bp ease. The usual Fed press mouthpieces have come out for a 25 bp ease. Surveys of economists all find that 25 bps is the most likely cut. Given this consensus, the Fed would lose another form of credibility were it to do anything else. Market participants would come to doubt the Fed’s ability to communicate. This has been a big issue for Bernanke, and I doubt he would put it in jeopardy over 25 bps.

One point about the argument our host offers. It is mostly a conventional hawkish-side argument. The dollar is a transmission mechanism for monetary policy. It is a feature, not a bug (in most cases), that the dollar falls in response to easier policy. To point out that it has fallen, and that a weaker dollar has consequences, does not address the balance of risks, but rather just points out one set of risks. There is always a inflationary implication to easing, just as there is a dollar implication. Pointing it out is not the same as showing that the inflation risk is too large to tolerate. It is always possible to argue (and very frequently is argued) that since 25 bps won’t make a big difference, the Fed can just skip doing it. This is the argument of those opposed to whatever move is contemplated. The fact is that a 300 bp move is just 12 increments of 25 bps, and I don’t think anybody would argue that 300 bps doesn’t matter. A 25 bp cut does as much good as a 25 bp cut does. Pointing out that the impact is likely to be small is not an argument against doing it. Identifying the broken sector (housing) while ignoring the health sector (exports) and the virtuous implications for trade and the current account and savings misses the way that the Fed does its job. The Fed tries to balance risks, to balance costs and benefits. Identifying one set of risks, citing only the costs and not the benefits, from a particular policy option doesn’t really help us.

When cab drivers, doormen, hairdressers (or barbers) and escorts are talking about prices, then the credibility of a central bank is already gone.

Guess what,

they all are.

The only “community” that does not quite get it yet is the “community of university-based economists,”

and even some of those “academic papers” types are starting to toss and turn.

I’m a radical hawk or conservative when it comes to monetary policy, so I more than agree with your recommentation James Hamilton and fear your argument smacks of ‘hyper reasonableness’.

esb: You are so wrong. I would guess that the vast majority of freemarket academic economists who work or dabble in macro policy support some version of inflation targeting/average price targeting. The problem is the current dual mandate of the US federal reserve bank and the well known time or dynamic inconsistency problem it creates with the creation of significant short-term rent-seeking opportunities for influential economic agents.

Ironically enough, American academic economists have been largely responsible for advancing the literature behind central bank reforms implemented in a number of rich western countries–New Zealand, Canada, the UK, EU, etc.–but not yet the USA.

My concerns

Beyond the immediate circumstances, monetary policy is the wrong instrument for much of what currently ails the US economy. Appropriate fiscal, natural resource, and energy policies should address these high commodity prices and improve US trade balances. With the appropriate domestic measures in place, the USA would be placed to maintain the status quo in the Middle East and to continue to help Israel consolidate territory taken in 1967, which, if I understand correctly, is an important non-partisan social goal that most Americans strongly support.

My immediate concern is that the option of ‘standing pat’ has not been sufficiently signalled/communicated/discussed, and the negative shock will be much greater than strictly necessary to get the job of stabilizing the inflation rate done. But if was up to me I would gladly take that risk as US fed credibility is at stake and that hard-to-earn, easy-to-lose capital is critical for the welfare of all Americans.

James, I think the markets have already priced in 2 1/4. We’ve seen a turnaround on dollar/euro. This should propagate through to oil, which has been range-bound this week.

Prof. Hamilton:

I have no points of contention. I’m curious though: Why did you choose to display the rates on jumbo mortgages over the past 6 months in the beginning of your post? You could have shown the opposite effect with conventional mortgages – rates declining over the past 6 months.

10/04/2007, 6.37

04/17/2008, 5.88

It seems like you were data-mining.

I, for one, doubt there is much that can be done to avoid a repeat of the 70s. Commodity production moves slowly in large cycles. It takes large swings in price to move markets and years to respond. A severe prolonged recession or very slow growth for a long time may be the only cure.

This sometime Post Keynesian is in full agreement with your position, Jim. This is a time when the more hawkish stance looks the best, for a lot of reasons.

And, yes, food prices are more important than oil prices, but the two are connected. Need to bring them both down, although the food ones will take a longer time.

JDH,

The monetary base has been stagnant since the Fed began cutting rates. Broarder money aggregates have grown, but the likely driver for that is flight to safety in money market funds.

So basically, you are saying that the Fed should abandon its objective of growth in the monetary base.

Who said that was the Fed’s objective? No one really. However, we have Bernanke’s speeches and writing to fall back on for guidance. The Chairman has argued that the 1930’s Fed and 1990’s BOJ can be fairly blamed for their countries deflation — because they allowed the monetary base to stagnate or shrink. They should have resorted to “unconventional measures”, if necessary, to reverse that trend.

So at this juncture, an influential economist is advising the Fed to hold its fire in order to defend the currency. Yet Bernanke has criticized the 1930’s Fed’s preoccupation with the dollar over the monetary base.

In the Bernanke play book, Fed Funds rate cuts are merely a step down the path towards monetary base growth. If they don’t accomplish the objective, then rate-targeting should be abandoned in favor of quantitative easing. Where does your advice for a pause fit in that play book?

BTW, I think Bernanke was wrong to begin with (on the BOJ and the 1930’s Fed); but surely, he doesn’t think so.

An addendum to my earlier comment.

1) We may not be able to seriously bring down oil prices for the longer term, but there does appear to be a speculative element in the short run that could be punctured by puncturing the expectations lying behind the market behavior. This would do a lot to puncture similar phenomena in several other commodity markets.

2) Food is indeed more serious, and my feeling is that while it may come down more slowly in the short run, it may do better in the longer run. The problems in the Saudi oil industry are serious and do indicate the likely impending global peak oil point, even if we might not quite be there yet. But, oil production is not going to seriously rise.

The food sector is more flexible, and good weather in Australia and some other places could lead to a very different scenario. OTOH, although few remember it, the last time we had a price spike in food (due to a weird deal between Nixon and Brezhnev never publicized in 1972, plus some bad weather), the prices stayed up until the spring of 1975, when they rather suddenly crashed back to what they remained until recently (basic grain prices that is).

3) While I outed myself as a “sometime Post Keynesian,” that has usually been modified by the term “complexity,” which some of the panjandrums of the PK school (notably Paul Davidson, editor of the JPKE), do not consider to be proper PK economics, although that is a matter regarding which there has been a long debate, and on which I disagree with him. But, there are broader and narrower interpretations, :-).

David Pearson,

With the advent of the bank sweep program in the early 1990s, the monetary base lost all of its significance as a money indicator.

Furthermore, as the dollar has been losing value, international demand for the physical currency has diminished significantly. Third world citizens are no longer holding physical dollars as inflation protection against their own currencies.

fed cuts ==> weaker dollar

Weak dollar ==> commodities speculation

Rising cost of necessities (a fcn of oil) increase the likelihood of global recession

All of which exerts negative pressure on US exports.

The idea that fed policy will provide a long-term improvement to the current account deficit seems silly.

We’d be better off if the fed engineers a collapse in home prices and then socializes the debt. It’s going to happen anyway, and would allow consumers to continue what they do best.

To Charles who wrote:

I’m curious though: Why did you choose to display the rates on jumbo mortgages over the past 6 months in the beginning of your post? You could have shown the opposite effect with conventional mortgages – rates declining over the past 6 months.

The conventional rates have been fluctuating over the last six months, but they really haven’t gone down. Instead of choosing a high and a low point, it would be more honest to look at a chart covering that period. See, for example:

http://www.marketwatch.com/tools/pftools/rates/RateChart.asp?sid=159412

and

http://www.marketwatch.com/tools/pftools/rates/RateChart.asp?sid=159413

My last comment should have been addressed to ‘matt.’ My apologies to Charles.

I am getting the feeling the market is already discounting the FED pause. Gold is off considerable from its highs as are the Ags.

Jodie,

Both valid points. However, they obscure a simple truth: the best measure of the effectiveness of Fed actions is growth in bank reserves. The stagnating base and the high LIBOR spread to Treasuries are two sides of the same coin: at 2.25% FF there is no incremental demand for injections by the system. The reason, of course, is that banks are delevering and reluctant to lend to one another.

My basic point is that the Fed has made strides in curing the illiquidity “symptoms”, but he disease of insolvency/develevering remains. It is this disease that the Fed (Bernanke/Mishkin/Kohn) believes can be treated (not cured) through money growth. The objective of the treatment is to prevent the flu (a credit crunch) from turning into pneumonia (a deflationary recession/depression).

So if you were at the Fed, how would you measure the effectiveness of the treatment? Bank reserve growth is a logical place to start, as is a decline in the TED spread. For reserves to grow, we need either 1) lower Fed Funds; or 2) quantitative easing (force feeding).

I am sure you realize this but bank reserves and monetary base aren’t exactly the same thing even though they are related. Because of sweeps, banks can effectively convert most reservable type accounts into accounts that do not have reserve requirements. Thats why reserve data don’t tell us anything. We need to look elsewhere. Looking at a broader spectrum of money like instruments its hard to make the argument that money isn’t growing rapidly. We can argue about the reasons, whether flight to quality or FED engendered, but money and credit are growing rather briskly right now. YTD bank credit has expanded 6.7%. MZM is growing fast as are other, broader monetary aggregates.

Also looking at economy wide macro data it is hard to see the effect of contracting money. Whether commodity prices, foreign exchange rates or current account deficits, the tell tale signs of contracting money supply are just not there. One could argue these are not symptoms of an expanding supply of money. They could very well be an indication that demand for money is weakening. Nevertheless, in either case, “force feeding” more money into the system would be a disaster for the Dollar.

In fact, what concerns me is the extent to which the private credit markets are getting guarantees from the Treasury and financing from the FED. Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, FHLB, TAF, TSLF etc., are all slippery steps to socializing credit. These measures are obviously helping the credit markets (2yr treasury yields are up to 2.4% from 1.25% before BSC), but the cost is that the Dollar’s purchasing power keeps eroding. It is time for the FED to halt its easing cycle.

Finally a note regarding TED spreads. There have been some doubts raised about the accuracy of cash Libor rates from banks which has led to some disengagement from this market. Other credit spreads have been narrowing markedly (ie. Munis, MBS, Corporates).

Jodie,

Bernanke is unlikely to have changed his view of history. It is precisely the dollar/deflation trade off that Bernanke has made a career out of promoting. I think its highly likely that an academic like Bernanke would now say “never mind” about his life’s work. Neither would Mishkin go back on what he has written more recently. Finally, Kohn has also argued that the dollar is less of a concern.

As you say, Bank reserves are corrupted by sweep accounts. However, broad money aggregates are not a good measure for the effectiveness of monetary policy since they grow as securitized credit contracts, and as velocity falls. If credit is growing we should see growth in the monetary base, a rise in non-borrowed reserves, and a fall in the LIBOR spread.

I admit this is all very “squishy” in the sense that the numbers paint a cloudy picture. But the issue is not how we interpret it, but how the Fed does. I believe they should defend the dollar, but I’m not talking about they “should” do, I’m talking about what they (likely) “will” do. The bottom line question is whether the Fed will abandon the rate targeting regime in the next six months. In the absence of narrow money growth, I believe the answer is yes.

As far as credit spreads are concerned, they are still elevated — hardly a sign of impending credit growth.

What do you think the Fed will (as opposed to should) do?

Sign me up as a disciple of James Hamilton and E. Poole. I believe the risk to the credibility of the Fed as an inflation fighter is too high at this point for any other action but that recommended by Mr. Hamilton. Hyper reasonableness indeed.

A non-economist here. I would like to know why if 1) a key attribute of the commodities whose prices have inflated is that they are storable and 2) the people, e.g. Krugman, who’ve looked at inventories have concluded that these commodities are not being stored, why is that not considered in the reasoning in this post?

Is there some other evidence that the commodities are in fact being stored? Lots of tankers sitting out on the high seas? Where’s the rice?

Russell, some answers to your questions can be found here and here

Thanks JDH for the pointers. If I parse those two posts carefully, and superpose onto them this one, I am unable to avoid inferring that neither you nor anybody else knows for sure. (That’s not intended to be negative in any sense at all)

This is just fascinating to follow as it unfolds.

Might be a good time to be a PhD student in economics.

The FED’s powers are limited. And it looks like the FED has already eased. But, I would vote with Hamilton.

The FED’s power over the current account deficit is confined to short-term interest rate differentials. Long-term the FED is completely powerless over exchange rates. Long-term the dollar is doomed.

The FED’s primary mandate is to control inflation and serve as a lender of last resort where there are liquidity & solvency problems with banks. The other mandates cited by monetary authorities (Mishkin) are ridiculous because they are impossible.

Before the turn in the seasonals, the FED has followed an extremely “easy” monetary policy, hence the rise in most commodity prices, including the “administered” price of oil.

E.Poole has it really right.

NOTE: Friedman’s “high powered money” otherwise know as the monetary base, is not a base for the expansion of the money supply. An increase in the base resulting from an increase in currency held by the non-bank public is deflationary, other things being equal. Anyway the publics desire for currency is at the espense of other bank deposits. As currency grows, bank deposits shrink, on a one-for-one basis (thus there is no change in the money supply).

Also, bank reserves are no longer binding/constraining. In 2002 70% of the member commercial banks didn’t have any required reserves. We are on a boat without a rudder or an anchor. I.e., the Fed can’t control the money supply with bank reserves nor interest rates.

Flow5,

the output and unemployment mandate is not “ridiculous” because it is a legal requirement enacted by the Congress whose laws the Fed governors swore to uphold in carrying out their duties. You may not care about it but that does not mean that the Fed can the law.

Yeah, I’m dogmatic:

It isn’t within the power or responsibility of the Federal Reserve to hold unemployment or even Gross Domestic Product to “tolerable” levels.

In fact, to assume that the Federal Reserve can solve our unemployment problems is to assume the problem is so simple that its solution requires only that the Manager of the Open Market Account buy a sufficient quantity of U.S. obligations for the accounts of the 12 Federal Reserve District banks. This is utter naivete.

You want real-gdp growth? Get the member commercial banks out of the savings business. What would this do? The banks would be much more profitable, interest rates lower, the supply of loan-funds higher, etc., etc.

Commercial banks do not loan out existing deposits saved or otherwise. Money flowing “to” the intermediaries (intermediary between savers & borrowers) never leaves the MCB system as anyone who has applied double-entry booking on a national scale should know.

.0.64…………0.20…………0.51..Jan

.0.23………..-0.41………..-0.49..Feb

.0.05………..-0.18………..-0.15..Mar

-0.03………..-0.09………..-0.13..Apr

-0.11………..-0.08………..-0.12..May

Now if I can get this to read right, then you will see that we have had negative rates-of-change for real-gdp the beginning of this year. May is the bottom. All rates-of-change after May are positive.

That is, interest rates must have bottomed. And coinciding with the change in direction associated with practicing the real-bills-doctrine, commodities turn c. sometime between the FOMC meeting & May 5th.