As I noted in a previous post, monetary policy works through various channels, one of which is the “bank lending channel”. Lower policy rates, as witnessed in the past few months and shown below, should induce greater lending.

Figure 1: Nominal effective Fed Funds rate (blue), and real (red). NBER-defined recession dates shaded gray. Real Fed Funds rate calculated by subtracting lagged CPI-All 12 month change. Sources: Federal Reserve Board via St. Louis Fed FREDII, and author’s calculations. Note: sample period used in Cetorelli and Goldberg is 1980Q1-2005Q4.

According to a new paper by Nicola Cetorelli and Linda Goldberg, presented at a recent Bundesbank conference, the magnitude of the impact depends on the degree to which the banking system is internationalized.

While the usual tendency to associate financial globalization with the increasing internationalization of bond and equity markets, recent events have brought home the reality of the increasing internationalization of banks. From the introduction to Cetorelli and Goldberg:

Monetary policy transmission through banks has long been noted as one of the

key channels for policy effectiveness. Seminal work by Kashyap and Stein (1994, 1995,

2000) shows that this lending channel differs across players within the financial system

of the United States. While lending of small banks appear to be highly responsive to

monetary policy shocks, the same is not true for larger banks. The main reason for the

difference within the population — the authors argue — stems from the presumed greater

ability of large banks to substitute reservable deposits with other external sources of

funds, so that the shock to the liability side of their balance sheet from monetary policy is

not transmitted to the asset side.…

…We conjecture and

show that this process of “globalization” of U.S. banking has had a deep and pervasive

impact on the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. Barring truly global events, banks with activities in multiple countries can reallocate funds in the event of a liquidity

shock occurring either domestically or abroad. Our argument thus presumes that banking

organizations actively operate internal capital markets, in which the global banks move

liquid funds between domestic and foreign operations on the basis of relative needs.

Hence, according to this conjecture the shock to reservable deposits caused by a change

in monetary policy would be absorbed through internal sources of funding rather than

exclusively through an attempt to access external capital markets.

…

Our results also show that the total lending channel consequences of U.S.

monetary policy are underestimated by a focus purely on U.S. markets. We look at the

response of lending of the foreign offices of U.S. global banks to a change in domestic

monetary policy and find evidence consistent with this the existence of an international

mechanism of transmission of monetary policy. Hence, monetary policy through the

lending channel may not be losing its effectiveness overall but rather it may be

increasingly felt outside of the traditional field of observation. In this sense, our work

directly compliments the Peek and Rosengren (1997, 2000) findings that banks are

specifically involved in the international transmission of shocks. In our case, results based on bank-specific data demonstrate a direct mechanism underlying the type of

monetary policy transmission across countries documented in analyses of

macroeconomic data, as in Kim (2001), Neumeyer and Perri (2005), Canova (2005) and

Goldberg (2005).

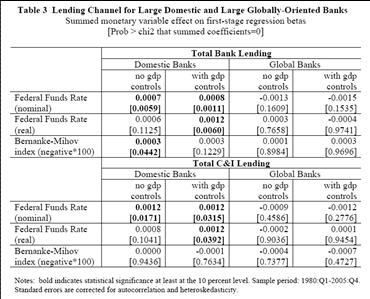

The differential between the impact of monetary policy shocks to bank lending in domestic versus international banks is highlighted in Table 3 from the paper.

Table 3 from Nicola Cetorelli and Linda Goldberg, “Banking Globalization, Monetary Transmission, and the Lending Channel,” mimeo, May 19, 2008.

[The results of this table are interpreted in the last paragraph of the empirics section:

…consider the counterfactual of an increase in the share of global banks by

another 10 percentage points, to 75 percent of total domestic lending.

For a lower bound on this impact, we assume that total lending issued by nonglobal

banks, large or small, has the sensitivity to monetary policy estimated for the large

banks, at 0.13 percent, as in the numerical exercise described after Table 3. Total lending

by non-global banks was about $1.8 trillion in the fourth quarter of 2005. Assuming a

median loan growth rate of 1.9 percent, an increase in the Federal Funds rate of 100 basis

points would reduce loan growth by about 7 percent, “shaving” loan growth by about

$2.3 billion over eight quarters. If the share of total lending issued by global banks were

instead 75 percent of the current $4.8 trillion, monetary tightening would have instead

reduced lending by about $1.56 billion. While this is still the same 7 percent reduction in

loan growth, it amounts to a 33 percent reduction in the amount of new lending that is

affected by monetary policy through the lending channel.

section added 5/27]

In terms of the current situation, my interpretation of these results is that the loosening of monetary policy, at least as measured by the real Fed Funds rate, will have a smaller effect on domestic macro activity than otherwise, as global banks shift around funds between the parent firm and affiliates.

Note that while the expansionary impact of monetary policy on domestic activity is attenuated by this effect for international banks, the contractionary effect of monetary policy is also reduced, should the Fed raise interest rates to reduce inflationary pressures.

The results of this paper are consistent with the view that while loosening of US monetary policy might induce greater lending overseas by branches of US banks, thereby tending to support rest-of-world economic activity, they also imply that negative shocks to the assets of US banks will also tend to reduce lending abroad. Hence, deleveraging by domestic banks has global (or at least rest-of-OECD) implications. That means both negative and positive shocks will be propagated abroad. In this sense, I think decoupling of the major developed economies is even less likely to occur.

Technorati Tags: recession,

credit view,

monetary policy,

bank lending, international banks.

I think we mean that the finance industry operate globally like other sectors, including semi-monopoly effects.

Irrespective of money variation, the automobile industry would react to technology shocks much the same way.

Menzie wrote:

In terms of the current situation, my interpretation of these results is that the loosening of monetary policy, at least as measured by the real Fed Funds rate, will have a smaller effect on domestic macro activity than otherwise, as global banks shift around funds between the parent firm and affiliates.

This perpetuates the myth that lower interest rates are a loosening of monetary policy. This is only true at the extremes of interest rates. The myth grows from a misinterpretation of Wicksell by mostly Keynesian economists. In truth the FFR does very little to the monetary situation because the FED has to still supply the market with all the money it demands to defend their rate. The general effect on monetary policy by the FFR is nil, but it does have a fiscal effect.

May 27, 2008

Menzie Chinn of Econbrowser posted a good piece over the weekend, How Effective Will Monetary Easing Be? The Bank Lending Channel and the Implications of Increasingly Internationalized Banks, reviewing a paper presented at a recent Bundesbank conferenc…

Commercial banks create new money when they make loans-deposits, etc. The volume of the loans they make is determined by monetary policy, not some international banking syndicate. These outside banks are not therefore “sources” of loan-funds. I.e., CBs do not loan out deposits. In fact CBs are custodians of stagnant money. And if there were any adjustment in monetary policy resulting from Euro-dollar influences, it would likely be sterilized.

Anyway, the money supply can never be managed by any attempt to control the cost of credit. This analysis derives from the Keynesian inspired concept that interest is the price of money, not the price of loan-funds. Therefore the FOMC decided it could manage the money supply through interest rates, specifically the FFR. Keynes was wrong on many important economic ideas.

flow5 wrote:

Commercial banks create new money when they make loans-deposits, etc.

flow5,

This is a falacy that is a misunderstanding of Austrian economics. Money can only be created by Central Banks. To see this create an imaginary economy with, say, $100 total. Using T-accounts attempt to increase the money supply without some exogenous interference with the supply.

You will see that debits equal credits and so there is no increase in the money supply, but introduce a Central Bank that can print more money and you will have an increase in the money supply.

‘flow5’ has it mostly right regarding money creation.

To see this, just take a step back from the theory and consider the difference between long and short term.

Commercial bank lending *does* inflate the money supply temporarily, where ‘temporarily’ means until the loan is repaid in full with interest. But until repaid, the effect is the same as pure monetary creation.

Now consider the effect of bad loans (where the loans were created from credit not from deposits being recycled): if not repaid, whether monetized by central banks (such as the Fed’s ‘term auction facilities’) or not, they become a permanent increase in the money supply.

Welcome to the wonders of fractional reserve lending. Central banks are losing much control over the expansion of the money supply. The inflation we now have in the system is the result of excess credit finding a home in malinvestment worldwide, where the credit creation is made permanent when the borrower defaults.