Various individuals have argued for drilling in the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) as a means to affect the price of oil. This is true despite this recent assessment by the Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration, the Federal Government’s nonpartisan analytical group on energy issues. From Annual Energy Outlook related analyses (June 2007):

The OCS is estimated to contain substantial resources of crude oil and natural gas; however, some areas of the OCS are subject to drilling restrictions. With energy prices rising over the past several years, there has been increased interest in the development of more domestic oil and natural gas supply, including OCS resources. In the past, Federal efforts to encourage exploration and development activities in the deep waters of the OCS have been limited primarily to regulations that would reduce royalty payments by lease holders. More recently, the States of Alaska and Virginia have asked the Federal Government to consider leasing in areas off their coastlines that are off limits as a result of actions by the President or Congress. In response, the Minerals Management Service (MMS) of the U.S. Department of the Interior has included in its proposed 5-year leasing plan for 2007-2012 sales of one lease in the Mid-Atlantic area off the coastline of Virginia and two leases in the North Aleutian Basin area of Alaska. Development in both areas still would require lifting of the current ban on drilling.

For AEO2007, an OCS access case was prepared to examine the potential impacts of the lifting of Federal restrictions on access to the OCS in the Pacific, the Atlantic, and the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Currently, except for a relatively small tract in the eastern Gulf, resources in those areas are legally off limits to exploration and development. Mean estimates from the MMS indicate that technically recoverable resources currently off limits in the lower 48 OCS total 18 billion barrels of crude oil and 77 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (Table 10).

Although existing moratoria on leasing in the OCS will expire in 2012, the AEO2007 reference case assumes that they will be reinstated, as they have in the past. Current restrictions are therefore assumed to prevail for the remainder of the projection period, with no exploration or development allowed in areas currently unavailable to leasing. The OCS access case assumes that the current moratoria will not be reinstated, and that exploration and development of resources in those areas will begin in 2012.

Assumptions about exploration, development, and production of economical fields (drilling schedules, costs, platform selection, reserves-to-production ratios, etc.) in the OCS access case are based on data for fields in the western Gulf of Mexico that are of similar water depth and size. Exploration and development on the OCS in the Pacific, the Atlantic, and the eastern Gulf are assumed to proceed at rates similar to those seen in the early development of the Gulf region. In addition, it is assumed that local infrastructure issues and other potential non-Federal impediments will be resolved after Federal access restrictions have been lifted. With these assumptions, technically recoverable undiscovered resources in the lower 48 OCS increase to 59 billion barrels of oil and 288 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, as compared with the reference case levels of 41 billion barrels and 210 trillion cubic feet.

The projections in the OCS access case indicate that access to the Pacific, Atlantic, and eastern Gulf regions would not have a significant impact on domestic crude oil and natural gas production or prices before 2030. Leasing would begin no sooner than 2012, and production would not be expected to start before 2017. Total domestic production of crude oil from 2012 through 2030 in the OCS access case is projected to be 1.6 percent higher than in the reference case, and 3 percent higher in 2030 alone, at 5.6 million barrels per day. For the lower 48 OCS, annual crude oil production in 2030 is projected to be 7 percent higher — 2.4 million barrels per day in the OCS access case compared with 2.2 million barrels per day in the reference case (Figure 20). Because oil prices are determined on the international market, however, any impact on average wellhead prices is expected to be insignificant.

Similarly, lower 48 natural gas production is not projected to increase substantially by 2030 as a result of increased access to the OCS. Cumulatively, lower 48 natural gas production from 2012 through 2030 is projected to be 1.8 percent higher in the OCS access case than in the reference case. Production levels in the OCS access case are projected at 19.0 trillion cubic feet in 2030, a 3-percent increase over the reference case projection of 18.4 trillion cubic feet. However, natural gas production from the lower 48 offshore in 2030 is projected to be 18 percent (590 billion cubic feet) higher in the OCS access case (Figure 21). In 2030, the OCS access case projects a decrease of $0.13 in the average wellhead price of natural gas (2005 dollars per thousand cubic feet), a decrease of 250 billion cubic feet in imports of liquefied natural gas, and an increase of 360 billion cubic feet in natural gas consumption relative to the reference case projections. In addition, despite the increase in production from previously restricted areas after 2012, total natural gas production from the lower 48 OCS is projected generally to decline after 2020.

Although a significant volume of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil and natural gas resources is added in the OCS access case, conversion of those resources to production would require both time and money. In addition, the average field size in the Pacific and Atlantic regions tends to be smaller than the average in the Gulf of Mexico, implying that a significant portion of the additional resource would not be economically attractive to develop at the reference case prices. [Emphasis added — mdc]

Here is Figure 20 from the report, showing the impact on lower-48 production in the baseline and the alternative.

Figure 20 from Annual Energy Outlook related analyses (June 2007).

What exactly is “insignificant”? One can get an idea by doing a back of an envelope calculation. The 3% increase by 2030 cited by the 2007 Annual Energy Outlook analysis works out to 0.163 millon barrels per day (mbpd) incremental production. Projected world output of conventional oil in 2030 is 99.30 mbpd. This means access to the OCS would result in a 0.164% increase in output.

Let’s appeal to a supply-demand framework, assuming log-linearity:

qs = a1 + a2ps + a3X

qd = b1 + b2pd + b3Z

Where q is log quantity, p is log price, X and Z are other shift variables, assumed to be exogenously determined. ai and bi are parameters, a2 > 0 and b2 < 0. Z could be income, for instance.

Solving the simultaneous system of equations for the equilibrium price leads to:

p = (a1-b1)/(b2-a2) + (a3X-b3Z)/(b2-a2)

Taking the total differential and holding constant the shift variables X and Z leads to the following expression:

Δp = (Δa1–Δb1)/ (b2-a2)

Substituting in some parameter values, taking Δa1 as the percentage increase in supply, namely 0.164% (0.00164), and setting the price elasticity of demand equal to -0.4, and and price elasticity of supply to 0.3 (Perloff and Whaples has cited these figures; plausible alternative parameter values would not alter the results in a qualitative fashion) yields the following: The resulting change from baseline in 2030 is -0.00234 (-0.23%). Taking the AEO 2008 baseline estimate of 70.45 2006$/barrel in 2030, the implied reduction in price is 0.165 2006$.

Now let’s conduct some sensitivity analyses/robustness checks.

Intertemporal Considerations

There have been some assertions that driving down prices in the future will have an impact today (see e.g., EconLog). Since petroleum is durable, there is no doubt that this must be true; the question, as always, revolves around the quantitative magnitudes. Take the 2030 impact on today; one can calculate the present value of the innovation: (1+r)22. Take r = .027 (which is the average ten year constant maturity yield minus the lagged one year inflation rate over the 1976-2008 period), one finds that the 0.165 2006$ decline in 2030 results in a 0.106 2006$ decrease today.

Alternative Estimates of Reserves

As pointed out in several venues [1], there is some debate over the amount of technically recoverable oil in the OCS that currently not accessible; the CS Monitor editorial argues that there’s been a big revision in estimation technologies. That may be, but here is a quote from the February 2006 report to Congress from the MMS of the Department of Interior (page xii):

Many proponents of domestic energy security consider gaining increased access to Federal resources to be one of the biggest challenges. Part or all of nine OCS planning areas, which include waters off 20 coastal states, have been subject to longstanding leasing moratoria enacted annually as part of the Interior and related agencies appropriations legislation, or are withdrawn from leasing until after June 30, 2012, as the result of presidential withdrawal (under section 12 of the OCSLA). Some of these areas contain large amounts of technically recoverable oil and natural gas resources. The MMS estimates that conventional oil and gas resources (i.e., UTRR) in OCS areas currently off limits to leasing and development total 19.1 Bbo and 83.9 Tcfg (mean estimates). There remains today, considerable uncertainty concerning the resource potential of many of these OCS areas. The availability of additional modern G&G data could reduce this uncertainty. It is instructive to note that perceptions concerning the resource potential of the Central, Western and portions of the Eastern GOM, areas experiencing robust levels of exploration and production effort, have continued to evolve for the better over the years. Critical to the changing perception is the fact that the MMS has acquired approximately 1.75 million line-miles of two-dimensional (2-D) common depth point (CDP) seismic data and nearly 300,000 square miles of 3-D seismic data. However, the additional G&G data and information that become available to assessors between assessments is frequently mixed in terms of having a positive or negative effect on the perception of the overall hydrocarbon potential of the OCS.

This implies that the EIA’s base assumptions do not appear unreasonable, on the face of it.

Alternative Elasticities

The calculations rely upon long run elasticities, and a constant elasticity along the curves (Note: linear demand and supply curves do not exhibit constant elasticities.) If the supply curve in log-price/log-quantity space was still backward L-shaped, and the supply enhancement occurred with demand intersecting along the near-vertical portion, then the price change would be larger.

What about short run effects (in 2030 say)? When new suppy comes on line, the resulting deviation in price from baseline will be commensurately larger in the short run. But by definition, over the longer horizon, prices will gravitate toward those indicated by the long run analysis.

Alternative timing

The calculations I presented focus on 2030. One could examine the effects of earlier changes in future prices. But as shown in Figure 20 (reproduced above), production does not even begin until 2017 assuming leasing begins in 2012 (less than four years from now!). Even assuming the 2030 effect is achieved in 2020, that would mean the resulting change in today’s prices would only be 0.12 2006$ per barrel.

Strategic Interactions

Reader Anon (in commments to this post) argues against my critique of offshore drilling arguments using a game-theoretic framework:

You are wrong. Opening up more acreage to exploration will affect psychology and markets. let me explain.

A credible threat of increased supply – even ten years away – certainly does have immediate impact to the ruminations of energy policy makers from Russia to Saudi to Mexico.

If you have a large control over marginal supply (Mideast/Russia/Mexico could all do a lot more if they choose to) and you see the glimmer of another North Sea or another ANS then you rightly might adjust your policies. Strategically speaking, if you dominate global oil supply then at some price point you rightly begin to fear Competitive Entrants.

…

In the case of Oil (by no means a free market), governments control access to resources (sell it like real estate and demand whatever they like or in many cases simply make everything off limits to private capital). However, if you push oil importing nation governments too far with overly high prices then you just might trigger competition.

I hope this makes it clear that the main reason we pay such high oil prices today is the government RESTRICTED ACCESS to reserves (a global phenomenon) that has tended to dominate the oil industry landscape for so long. The secure knowledge that the US Government is EXTREMELY UNLIKELY to open up new reserves for exploitation is enough to keep exporting nations confident that they can safely continue to extract higher rent for their commodity.

So just the credible threat of a surge in new competition (a la Bush statement) may be enough to open the taps a bit more or cause a flurry of counter-competitive increased supply activity to quickly try to KILL the new threat or frighten off competitive capital investment in new supply..

…

Think Strategically. BTW – I condemn Bush for many things and I sympathize with your attitude towards this administration, however, for once, Bush is actually right this time!

…

Anon admonishes me to read Barry Nalebuff’s book Thinking Strategically (actually it’s Dixit and Nalebuff); I confess I have not yet done so. But having endured some amount of game theory over the years, I’m going to wade ahead nonetheless.

First, consider this exchange from April 2004, where Nalebuff suggests investing $5 billion to enable Iraq’s oil industry to export a million extra barrels of oil a day, thereby negating OPEC’s monopoly power. One interesting aspect of Nalebuff’s argument is that he doesn’t propose something like exploiting US offshore reserves. I think the reason is quite simple, and is rooted in game theory — Iraq in principle can be a low cost producer (after security is established). Supply from offshore sources in the US would be (and is known to be) a relatively high cost (per unit production) venture relative to, say, Saudi oil production. Hence, it’s not clear increasing US production can have the strategic effect often suggested. (Example, see: [2])

I do agree with Anon that a lot of world production is undertaken by state owned enterprises, which lack proper incentives for responding to price signals. But I’m unconvinced that foreign state owned enterprises would be privatized simply because the US removed its moratorium on OCS exploitation.

So, opening up production in the currently inaccessible areas of the OCS might have substantial effects (perhaps on trade balance, or oil company profitability, Federal leasing revenue), but in my view is unlikely to have a substantial impact on oil prices (just as in the case of opening up ANWR).

As an aside, John McCain is still supporting a gasoline tax holiday [3], so on this count, I remain puzzled.

[Update, 17 August 9:30pm] Regarding potential costs.

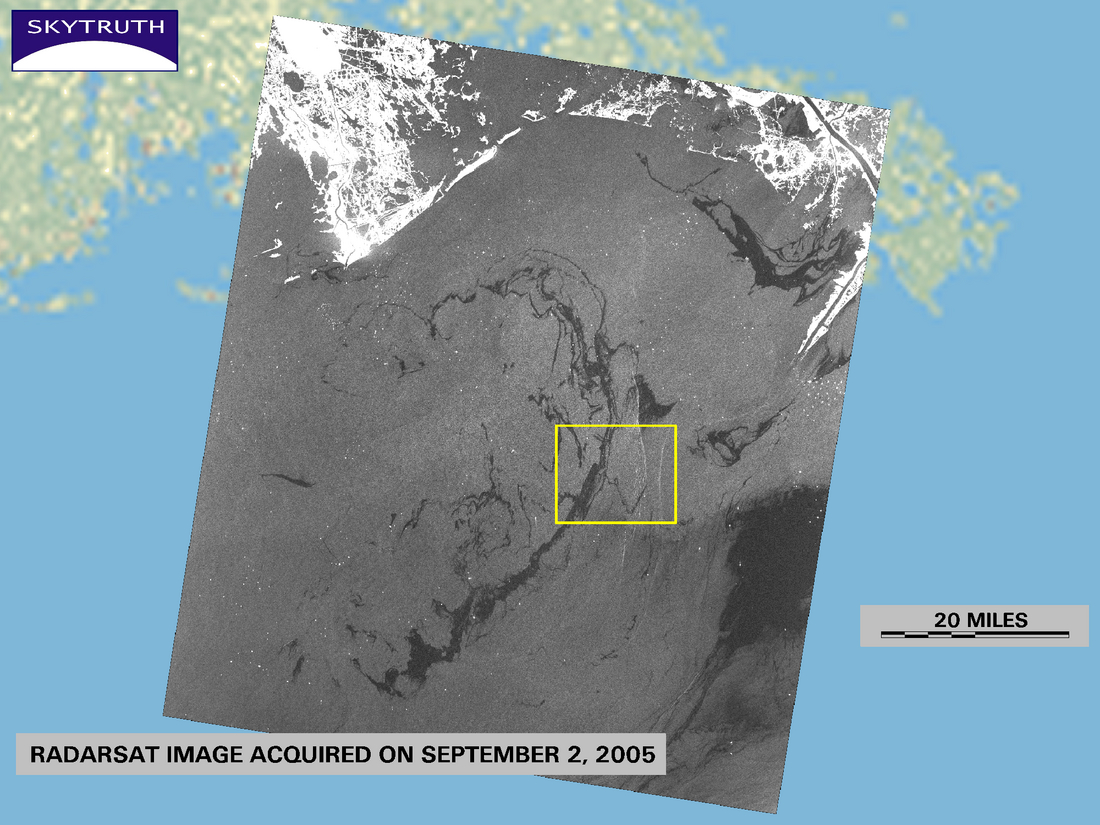

Source: Skytruth.

Radarsat-1 satellite radar image acquired on September 2, 2005, that shows extensive oil slicks in the Gulf of Mexico following Hurricane Katrina. Approximately 2,144 platforms and 15,366 miles of seafloor pipeline experienced hurricane-force winds; an additional 2600 platforms and 12,470 miles of seafloor pipeline were exposed to tropical storm-force winds. Yellow box shows location of area covered by a separate graphic showing details of leaking platforms. Oil slicks are dark patches; oil platforms are visible as bright dots. Land areas are also very bright. Original TIFF file is 200dpi @ 10″x7.5″.

Caption:

Satellite Image of Oil Slicks With Location of Detail – Leaking Platforms, 9/2/2005

DNV’s report to MMS estimates total spillage from Katrina and Rita from rigs and pipelines was 17,652.2 barrels, equivalent to about 1/14 of the quantity from the Exxon Valdez spill.

Technorati Tags: href=”http://www.technorati.com/tags/oil+prices”>oil prices,

outer continental shelf, offshore drilling,

oil reserves, elasticities.

I think people resist the logic of this because it doesn’t make common sense. More supply, a lot more supply should have some impact some time. Maybe the point is that it is not a lot of supply, it is almost no supply.

You could also apply this logic to raising taxes. We have, what, $59 trillion in debt, trillions more in unfunded government pension liabilities, medicare, social security…what good would it do to raise income taxes on the wealthy to 39.5%? You could calculate out the difference over thirty years and come up with, say, it will reduce .00023% of government obligations, therefore there is no point in raising taxes.

My fear is that if we don’t do something we are going to end up with $12 a gallon gas and a severe depression. We are going to need oil, and lots of it, for a long time. It is going to take a miracle to stop that now, I guess.

Doesn’t assuming influence of the “threat” of our producing more oil ignore the “demand” aspect of the argument? Overwhelming.

Is anyone here naive enough to think oil produced here won’t be sent to the market and sold to the highest bidder?

Is anybody here even acknowledging the effects of the speculators in our wide-open and largely unprotected commodities market? The Congressional action to halt the damage that resembles a slow motion video?

The continuing attacks on the golden goose may yet kill the attackers.

It would be great if we gave serious tax advantages to electric and other alternative cars. We cannot, as T Boone says, drill our way out of the demand acceleration long term.

But as long as oil men control government and foreign policy, little will be done to wean the USA off her petroleum addiction.

I view these oil men as being unpatriotic and primarily engaged in the greed of selling their product no matter what effect it has on the future economy of the United States.

Since when is the purpose of producing things to lower prices of said things?

If there was a $100 bill on the ground in front of you would you not stop to pick it up because it wouldn’t lower oil prices?

The question ought to be “What is the best use of this scarce resource for our society?”

The oil is worth billions of dollars, Said another way, it will meet billions of dollars of human needs. If we bend over to pick it up, that is.

There are some costs to our society to producing it. People might have to see oil platforms. There might be an occasional spill. Is avoiding these costs worth more than the value of the oil? Well, are people willing to pay billions of dollars to avoid them?

I doubt it.

But we are.

The first question that comes to mind is why should it take 4 years to BEGIN leasing?

We should also note that Congress has blocked new collection of data and refinement of resource estimates for many years now. Exploration is one area where substantial technical progress has been made and, based on past performance, the resource base can be expected to increase with better and increased data.

However, I would agree that the expected effect on retail prices has been overstated for reasons of political puffery. Still, it is time to open this national territory for the benefit of all citizens. Even discounting price savings, the revenues to the Treasury should be adequate reason.

congrats to Gary Anderson for furthering the narrow-minded “oil people are bad,” and “green energy/alternative promoters,” are good rhetoric.

Joseph:

does your last argument mean that you will vote for the democratic candidat?

Because I remember reading that the last leases made by the republican administration were not bringing so much money into uncle Sam’s vault.

“does your last argument mean that you will vote for the democratic candidat?”

When pigs fly.

I was just pointing out that offshore leasing will produce revenue for the Treasury for all US citizens. During the Clinton Administration, the rules on lease terms were modified to encourage riskier deepwater exploration. If those rules carried over, and the drillers were not particularly lucky, then more recent leases might not have been as good revenue harvesters as earlier ones.

The terms for new leases can be revisited. However, the goal for new offshore and ANWR leases should not be revenue maximization but some balance of lease revenue and physical production.

This sounds very much like the same arguments that were made 10 years ago against more domestic drilling…its not enough, and it will have an almost negligible impact on price. Love him or hate him, oil prices took a nosedive shortly after Bush started making noise about drilling offshore…and have remained down even after the Russians overran Georgia. Stale, esoteric economic models notwithstanding, it appears that noise from W has more impact on oil prices than Russian tanks.

Like diz said, we shouldn’t be looking at more drilling through the “will it lower prices?” lens. It most likely won’t, for better or for worse, so we can shelve that question and move on.

Reasons to drill: more tax revenue; bigger economy; better domestic energy capacity in case of war; now is the best time to sell a valuable resource.

Reasons not to drill: environmental damage, both local and global.

Totally stupid reasons, regardless of the side: it will/won’t change prices significantly; it will/won’t signal that we’re serious about alternative energy; it will/won’t give money to people I think are icky; let’s wait “until it gets more valuable.”

Actually, the issue is beyond offshore drilling. Congress has refused to clear the way for regulations related to shale oil production which has a vastly greater potential to impact oil supply.

The argument that a course of action has no value because it has no immediate results is specious and deceptive. Using that simplistic thinking… AIDS research is of little value because it may be 25 years before there is a cure and all we are doing is driving up medical costs for society [driving up environmental risks for society].

Either increased supply reduces prices by meeting demand or increased supply reduces the level of price increases by partially meeting demand. If you don’t believe in the dynamics of supply, demand, and prices, you should be reading RealClimate instead of Econbrowser… or writing there.

Diz and Dan Weber: Believe me when I say that the decision whether to drill should not hinge upon the price effect — that was something others have brought up. As always, I say a benefit-cost approach to the question is appropriate. Not that that is a simple task, since there is uncertainty regarding many of the key parameters, and apparently there is some dispersion in the weights attributable to environmental degradation (which is why I disagree with Joseph Somsel‘s assertion:

He surely must be more certain about the critical parameters than I am (or has near zero weight on costs or probabilities of environmental degradation).

I do not know what the impact on Federal revenue would be (for sure, given the 2001/03 tax cuts, we need as much of those revenues as possible). However, using the mid-point estimates for OCS oil production cited in the 2007 EIA analysis, the reduction in the US trade deficit would be around 59 million barrels per year times whatever price prevailing at that time, assuming one-for-one displacement of imports.

Mr. K: If your argument is your example of an “event analysis”, don’t try to publish it in an academic journal. By the way, when is game theory esoteric — it’s been around since at least since the 1950’s (I hope you’re not referring to supply and demand)?

Menzie – I am also aware that the sun rose on the same day tha W called for more drilling. You have just posted a prediction of sorts on the impact of drilling now in 2030; however, your pseudo-intellectual ecocrap cannot seem to explain the recent rise to near $150/bbl and now its drop to $113 in one month in the here and now! Do you predict climate change as well, perfesser?

Professor Chin,

Sorry, I didn’t mean to imply that your analysis was misplaced or unneeded. We definitely need economists to figure out what the price effect will be of more drilling.

Now that we have your answers, though, we can apply them to the policy question. 🙂

The argument seems to be that since we cannot totally reduce the price of oil with a change in US policy we should do nothing.

First, there is a difference between the affect of increased supply directly on the price of oil and the impact to speculation. Speculators go where the return is. If they expect their return to decrease they will move to better investments. Increased supplies especially when they are unknown will drive down the price of oil. No one can logically question this. As Menzie says it is a question of how much not if.

Then realize that other countries are pushing ahead with exploration at a huge pace. Brazil is buying all the oil drilling equipment they can and many of the machine manufacturers cannot keep up with Brazil’s demand. Increased US production is simply one part of a world strategy including solar, wind, nuclear, and every other viable production of energy.

While some want to put more into unproven speculation in alternative energy what we do know is that oil does supply energy. The risk of putting resources into unproven, economically questionable technology while restricting known technology is foolish on its face.

Menzie, what are the differences in costs and probabilities of environmental degradation by U.S. oil companies under U.S. regulations compared to those of other nations? In other words, will there be more or less environmental degradation by producing oil here or simply relying on others to supply it.

It is also quite obvious that demand elasticity increases at some price point. I suspect the elasticity would increase at an increasing rate at higher and higher prices so a linear demand curve is relatively pointless. What about supply?

As already pointed out, the benevolent department of energy’s forecasts do not impress me after watching recent fluctuations. If we give them even the modest laughter they deserve, how do you explain the recent decline in prices?

Anon is right. Psychology is a much better predictor then your economic forecast which cannot explain much even if the assumptions hold true which they don’t.

Dan Weber: Thanks for the clarification; no offense taken. I wanted to agree with your points that there are costs and benefits, and some asserted costs and benefits are besides the point.

Mr. K: I didn’t provide a forecast; I provided an implied change in price relative to baseline, based on standard supply and demand and present value calculations. If supply and demand, or present value calculations, constitute in your mind “pseudo-intellectual ecocrap”, then, with respect,I think your time is better spent reading posts besides mine.

Mr K. I was watching the oil market the day Bush made his statement. The market was not reacting to his speech. By the time he made his speech the market was already down sharply because EIA had reported that oil inventories were much large than thought.

I agree with Menzie that your analysis does not go far among people who know what they are talking about.

I totally agree with Menzie Chinn on this issue, great posting. He’s totally right that expectations about future oil production have no effect on the price today, that affects our everyday lives. People need to understand that that’s just an unproven theory, like evolution. Well, actually, evolution’s a pretty good theory 😉

I wonder whether any of the usual suspects will have the decency to acknowledge the graphic of oil slicks following Katrina. We have been hearing this horse manure about there having been no oil spills due to Katrina; the last time the calliope went around, I posted news reports of millions of gallons spilled just in southeastern Louisiana to rebut this zombie lie… and, of course, the usual suspects greeted facts with silence.

Here’s an easy game for the great theorist anon: I have bread. You are hungry. You are purpotedly building a big bakery. I think I’ll still charge you a lot of money for bread today, let tomorrow take care of itself. I don’t really think you’ll ever get the bakery up to much, anyway, and I have really good reason to believe that.

A serious gas tax upgrade schedule in hands with a hard-nosed CAFE implementation will do everything to the price of oil and more than offshore drilling.

But I bet even the thought of that will give diz, Somesel and the rest of the Business-As-Usual (because they have no imagination beyond kissing corporate butt even harder) posters the vapors.

Stop kicking the damn can down the road. We drilled in Alaska in the 70s. Didn’t bring nirvana, not even for a generation.*

Way past time to think of something different. The kids are counting on us.

*”Is anyone here naive enough to think oil produced here won’t be sent to the market and sold to the highest bidder?” — Clinton permitted the selling Alaskan oil to Japan when oil prices had crashed, despite promises to never do that. Wouldn’t it be nice to still have that oil in the ground now?

I agree with Anon’s points but, in the current situation, not his conclusion. How I define the current situation: 3.5 years of zero growth in global crude oil production. And, 3.5 years of falling production in NON-Opec. For Anon’s points to be true, the current situation needs to be defined almost exclusively by Scarcity Rent, and the Hotelling Rule. What’s truer is that both of these are in play (in support of Anon’s point) but so is geology. Also at play is the rising cost level of the marginal barrel, and, last but certainly not least, declining EROEI on oil production. (Declining energy return on energy invested).

Again, Anon’s points are excellent and I agree with them. They are not to be rejected. Rather they need to be augmented. The crude oil futures curve would only respond per Anon’s point, were scarcity rent and “above ground factors” the only thing at play. In that case, robust OCS drilling might yield a sustained repsonse in the long-dated futures. But I am confident that will not happen. The first OCS flows of oil, in meaningful quantities, are years away. By that time, geology, declining EROEI, soaring costs of the marginal barrel, consumption growth among oil producers themselves (declining exports) and geology will all have combined to chew through supply, and oil prices will be much higher.

The purpose, therefore, of OCS drilling is to create capital, not supply. Flows from OCS drilling will simply mean we can buy more of our own oil–rather than “more” of someone else’s oil. With the capital, we can build utility grade solar, and expand mass transit. i.e. boost the transition away from liquid fossil fuel (which will be less available to us).

Bottom line: OCS production will be a monetization of the resource. And that’s fine. I won’t lower long-dated oil prices, and won’t bring down the spot price either.

Menzie, if I follow your calcs, you are assuming delta b1 is zero. Economically, I believe this says there is no shift of the demand curve during the period. If, however, the demand curve were to shift + more than the supply curve shifts +, then the equilibrium price outcome will be reversed in sign, and by an amount proportional to the demand shift. Given real trends, a demand shift is likely to totally overwhelm the supply shift.

But I like your approach, which in any reasonable case suggests to me that drilling as a solution is whistling past the graveyard from a policy standpoint, making explicit that which is implicit in your analysis.

So, I propose the intelligent set of readers here focus on what can truly make a difference from a policy standpoint… taking carbon TOTALLY off the energy table. It can be done. But only if we set it as a national goal and invest accordingly to reap both the national (including economic) security and environmental benefits possible.

I note that sum of the current sustainable replacements is not yet sufficient to reach this goal, so we always fall back on carbon energy to plug the gap.

I propose we focus instead on scientific breakthroughs BEYOND current technologies to eliminate carbon energy. I believe there is evidence that these breakthroughs are there, and that it’s just a matter of will at this point to implement them. If I am even close, then we would be foolish not to invest.

Neither carbon nor current alternative energy sources are sufficient or sustainable. With what is around the corner in new science, neither is more than a temporary necessity.

I realize this is vague…but not knowing the posters here very well, I don’t want to be labeled as more of a crackpot than I actually am at the outset, so for now, I’ll leave it vague.

I do strongly discount the risk of significant environmental consequences of additional drilling. I base this on the vastly improved technology which is well proven. In addition, the consequences of oil spills are largely overplayed. While a spill can be a short-term mess, the petroleum is bio-degradable and the biosphere adapts. Oil spills are certainly disphotogenic (ie ugly) and the sight of oil-covered birds can be heart-rendering but in the bigger scheme of things they aren’t THAT bad.

One point that needs further explanation is that the resources of the offshore environment belong to all Americans yet the local coastal states want to control beyond the 3 mile limit. There is certainly some merit in their argument that they face consequences that the interior states won’t suffer but certainly a rebalancing of interests should be considered.

I’m on-board with oil shale too although I am skeptical of its EROEI. However, I’m willing to let private investors give it a shot under reasonable environmental impact regulation. Congress has not been willing to allow any oil shale development in Colorado where the main deposits are.

Steve Bannister: Δb1 is set to zero because in this thought experiment, I am assuming ceteris paribus. That’s to better isolate the partial effect. If one wanted to wish Δb1 = f(Δa1), that would be simple enough to incorporate, although offhand I don’t see why a supply shift for oil should induce a demand shift for oil.

Menzie. I understand and agree. I suppose I was motivated by the very big picture. So for price estimation ceteris paribus, I could argue that delta b1 and delta a1 are NOT correlated.

And my main thought on price equilibrium is that since the probable delta b1 effect in the real world is going to overwhelm the probable delta a1 effect in a carbon regime, we should look very seriously way beyond carbon for affordable energy.

And your analysis led me to think about all this somewhat differently. So not being critical, just extending.

All of the economic models that I have seen, regarding the impact of opening up the OCS for drilling, seem to be missing variables that account for the quality of oil found. Not oil is created equal, as poorer quality crude oil requires higher costs for refining. Recent DOE reports show that the quality of oil, which is highly uncertain, could dramatically affect the net benefits of opening up drilling in places like ANWR. A close friend of mine was also spearheading Sun Oil Co.’s (SUNOCO) Alaskan pipeline effort several decades ago in untapped areas, and he said that most of the oil was basically “vaseline-quality” petroleum.

I was wondering if the authors of this blog or any of its readers could explain how the quality of oil could affect the supply-demand model for the global price of oil (especially in the case that not all types of oil are perfect substitutes).

diz asked: If there was a $100 bill on the ground in front of you would you not stop to pick it up because it wouldn’t lower oil prices?

That’s not the right analogy. Suppose you saw a $100 bill on the ground and concluded that since you found a $100 here, there must be plenty more up ahead. So instead of a onetime windfall you misinterpreted the find and treated it as a permanent change in income. Then you decided to spend that $100 plus all those expected $100 bills that you just know are waiting for you up ahead. In that case it would have been better if you had never picked up that $100 bill. That’s what’s going on here. Listen to how passionate people are when it comes to opening up ANWR and offshore drilling. A surprisingly large number of people believe that $2 gallon gasoline is right around the corner if only Congress will approved offshore drilling. Do you really think that they would be this passionate about ANWR if they actually understood that the benefits would be years away and would only amount to a few cents a gallon? Diz would have a point if people actually recognized just how limited the benefits of ANWR and offshore drilling are likely to be; but people don’t recognize that. But people aren’t that smart. They are myopic and inclined to believe what they want to believe rather than the objective facts. And this all gets reinformced with McCain is out there promising voters that cheap gasoline is only months away. This risk is that opening up ANWR and offshore drilling is likely to give people a false sense of security about future energy supplies and as a result consumers might revert to their bad old habits.

“Disphotogenic:” the latest Orwellianism for dead birds and sea mammals, destroyed fisheries and livelihoods, and swimming beaches coated with black tar.

I suppose the term could also be extended to war zones, epidemic disease areas, and countries afflicted with famine.

I’ll have to remember that.

Perhaps the message is too difficult. Let’s see if it can be broken down into tiny bites of information that are easily digestible.

1. Offshore drilling is a possible source of increasing domestic oil, but not the only one.

2. There may be 1,000,000,000,000 barrels of oil in northcentral U.S. that can be economically recovered

3. There are methods for extracting that oil that are environmentally sound

4. Congress is the obstacle, not cost or technology

http://alfin2100.blogspot.com/2008/07/1-trillion-barrels-pelosi-and-boxer.html

If that is still too difficult, I’ll try to break it down further. And yes, it will take more than one year to affect gasoline prices at the pump, but in 10 years we won’t have certain politicians saying it will be another 10 years.

The reference case assumes that the world will produce 99 mbd of conventional oil in 2030, and that these barrels will sell for $70. Does anyone else think these assumptions are unlikely to be realized?

I’m with Gregor: Drilling won’t bring down prices significantly, but it’s worth doing for balance-of-trade and gov’t revenue reasons while we transition to non-oil transportation. Plus the possibility that oil might stop being fungible if the world really goes to hell in a political/war sense.

peace,

lilnev

Charles,

Please admit that some images have greater propoganda potential than their intrinsic effects merit. Worst than gooey birds are the baby seals. Some images touch emotional, hardwired points in the human nervous system.

The ability to view visuals with emotional detachment is one every adult should cultivate.

BTW, my career decision to become a nuclear engineer was triggered by my helping on an oil spill cleanup as a freshman college student. Since then, I’ve been able to put such things in a more mature prospective although it was a good decision.

Joseph,

You comments about the relative problems with oil spills versus other environmental problems is spot on. As a matter of fact environmentalists have probably caused more serious economic disasters than business, because if business does this they have liability while environmentalists simply shrug their shoulders and move on to create their next disaster.

Consider:

mercury filled light bulbs that need a haz-met team for disposal.

Ethanol that is burning up the worlds food supply.

Applaud them for facilitating the number 1 killer in the world by banning DDT in 1972. The 20th Century was the bloodiest in history and yet environmentalists have killed more than all the wars of the 20th Century, environmentalist have caused almost 100 million deaths.

I was wondering if the authors of this blog or any of its readers could explain how the quality of oil could affect the supply-demand model for the global price of oil (especially in the case that not all types of oil are perfect substitutes).

Old news. Back in the day, each individual refinery was built for a specific type of crude (for example, BP’s Cherry Hill refinery in Washington State was built to refine Alaskan Crude, exclusively). Crudes from different fields ARE different, and have different characteristics that can require special processes, metallurgy, etc.

But these days, pretty much every refinery out there refines crudes from different sources. And most of the big refineries are gearing up to be able to refine the heavier crudes, espcially the heaviest crude out there: Canadian tar sands.

Interesting fact: heavier crudes require a lot more natural gas to process (for furnaces) than lighter crude. In a sense, you’re turning natural gas into gasoline.

What does T Boone Pickens think about that?

New refineries in China and India are able to refine just about anything. The Reliance expansion in Jamnagar, India is so big that it will supposedly cause the price differential between light and heavy crude to close.

This is good news, it means we should be able to capture pretty much the full current value of the oil we have rather than some lower amount. We don’t increase the downside risk by putting our oil on the market.

Keeping oil in the ground is a fools game since we can’t borrow on the expected future value of that oil. By pumping now we limit down side risk and also benefit from the compounding effect of the new income and wealth generated from the oil. If we leave it in the ground, we limit upside risk but forgoe the income earned on the wealth generated by the use of the oil.

dick said:

“As a matter of fact environmentalists have probably caused more serious economic disasters than business, because if business does this they have liability…”

…with the exception of our current economic “disaster”, for which the taxpayer is liable.

Buzzcut touches on a point of interest – the role of hydrogen in alternative petroleum supplies. The “refining” of heavy oils, tars, and kerogens really resolves to adding hydrogen to improve the carbon/hydrogen ratios. Currently, we use methane (natural gas) as the source of that hydrogen.

Wonder why the “hydrogen economy” bandwagon got derailed so quickly? It was the realization that the most effective way to make hydrogen for fuel was via nuclear reactors using water as the input. Likewise, I think oil shale development will only come into its own with nuclear reactors to provide process heat for extraction of the kerogen and hydrogen for its upgrading into transport fuels.

Nice post Menzie. The rebuttal to Anon is excellent.

You make it clear that it will take more than an opening of exploration rights in the US alone to counter the cartel of government owned/controlled sources of production (around 80% of the market). After all, North Sea AND Alaska AND significant demand destruction/over capacity are what really helped keep prices of oil down in the mid 80’s and 90’s.

Clearly China, Europe, India and other big consumers must play a more active role too. Together, consumers may be able to achieve something if the problem is attacked on many fronts, however, divided we stand conquered by an oligopoly of nationally controlled supply with a limited incentive to dramatically raise production. Furthermore, these extensions of the state need to draw on oil profits for state uses (rather than a private company that tends to redeploy profits back into the same industry). Of course, there is nothing inherently wrong with these state enterprises – it seems to work in favor of exporters much in the same way farm subsidies work in the West – however the reality of their different drivers must be recognized by consuming nations who would obviously like to get the oil at a lower price.

Private Oil Co’s are enjoying huge profits at the moment and may be seen as the public enemy #1 but they are actually starved for options to deploy capital to increase production (many are buying back shares…which only helps Wall Street not consumers).

One point I will add to counter Menzie’s thought that high cost production is unhelpful to keeping prices down. This may be counter intuitive but it is precisely the high cost of production that keeps production high. The high infrastucture cost of Alaska and North Sea and Deepwater mean that companies (like large manufacturers) tend to maintain production – even in low price environments. This is partly what helps keep prices depressed during a supply glut – no one will cut back because overheads/running costs are too high to stomach it. Conversely, Swing producers gain by cutting back production and hopefully increasing the price on their substantial remaining production – and they have the kind of low overheads (lifting costs) that allow them to do so whilst remaining highly profitable.

Wonderful thread – lots of great comments too. Thanks again James and Menzie for your highly informative and insightful musings.

When his troops reached Vicksburg, U.S. Grant ordered an assault on the Confederate fortifications. He doubted it would succeed, but felt he had something to gain even from an unsuccessful assault: “The troops believed they could carry the works in their front, and would not have worked so patiently in the trenches if they had not been allowed to try.”

To me, this is the only compelling reason to drill the OCS. As a society, we will not fully commit to finding alternatives until we do so. We desire for our lives to stay more or less the same, and that desire makes us listen to those who claim that our behavior is in no need of change. That desire makes us listen when they invoke the shibboleth of environmentalism, when they tell us that the only problem is that we aren’t allowed to drill enough. Only when that drilling fails to significantly lower prices – and Prof. Chinn’s analysis is persuasive – will people roll up their sleeves and seriously address the difficult task of building a new energy future.

Of course, this is a Machiavellian and environmentally irresponsible argument, but I fear it reflects our situation’s psychological and political reality.

After all, North Sea AND Alaska AND significant demand destruction/over capacity are what really helped keep prices of oil down in the mid 80’s and 90’s.

Is that true? I always thought that prices broke in ’86 because the Saudis couldn’t afford to keep their oil off the market. They were the OPEC producer giving up all the production, thus raising prices (all the other OPEC producers were cheating).

Once the Saudis started pumping again, OPEC was broken, and prices plunged.

“Once the Saudis started pumping again, OPEC was broken, and prices plunged.”

The Chicken or the Egg? It all depends if you think OPEC would have broken if demand remained strong and non-Opec supply continued to dwindle (no Alaska no North Sea)?

There is no definitive answer, however, game theory suggests that “cheating” is the best strategy for those who are small producers in an oversupplied market. The logic is that “my limited incremental cheating” will not affect overall market price that much. Of course, collectively, a lot of cheats does just that! Also non-opec producers were inclined to maximize production anyay – due to higher infrastructure costs.

Another observation in Game Theory is that almost universally there has been observed a human “social” tendency to “punish” cheats, when playing successive rounds in a game.

Did the Saudi’s punish the “cheats” – it might appear so from some perspectives…

The key to strategic thinking is trying to figure out behaviour. For example, if importing nations (consumers) had thought carefully about things, they might have realized that Russia’s best interest might be served by limiting production growth rather than what consumers wanted/expected. Remember that 10 years ago, Russia was regarded as a cornerstone of future increased supply but today production is actually declining…

All this goes to show that Oil is very far from a “free-market” when it comes to supply.

“Keeping oil in the ground is a fools game since we can’t borrow on the expected future value of that oil. By pumping now we limit down side risk and also benefit from the compounding effect of the new income and wealth generated from the oil. If we leave it in the ground, we limit upside risk but forgoe the income earned on the wealth generated by the use of the oil.”

This is a variation of an argument Aaron has made over at Angrybear – to which I suggested he think of this in terms of a Hotteling dynamic optimization model. I guess his argument makes sense if one thinks the future price of oil will be no greater than today’s price. But Jeff Frankel recently criticized this view. I guess Jeff’s priors are that future oil prices will likely be higher than today’s prices.

The MMS estimates are based on extremely conservative leasing, development, and production

schedules… And of course, the relatively low prices that prevailed from 1980 to 2005/2006.

A more agressive approach could and probably would yield far more oil much more quickly. Too

give you some idea of what is possible, Brazil expects to add 1 MBD by 2015 (see

http://www.bnamericas.com/news/oilandgas/Petrobras_CEO:_2,8Mb_d_by_2015,_not_including_Tupi) not

including the subsalt Tupi field.

To put this in U.S. perspective, the MMS is suggesting that an incremental 200 KBD might be

produced in 2030 via additional leasing. However, a single U.S. OCS field, Thunder Horse is

projected to reach 250 KBD in the next few years.

Note that MMS is only covering the lower-48 OCS. Offshore Alaska is estimated to have more oil

than all of the other (currently closed) areas combined. See

http://www.flickr.com/photos/peter_schaeffer/2680989377/in/set-798097/ and

http://www.flickr.com/photos/peter_schaeffer/2681809002/in/set-798097/.

Of course, the onshore ANWR is generally thought to be capable of producing 1 MBD by itself.

At some level, the debate about OCS and ANWR development has an absurd element to it. OCS and ANWR development are deemed to be irrelevant if they can’t plausibly eliminate the need for oil imports and/or drive down world oil prices. However, none of the proposed alternatives have any prospect for achieving the same goals either.

Will windmills, conservation, or biofuels make the U.S. energy independent? None of them has any prospect of doing so. Could a combination of wind energy, conservation, biofuels, OCS/ANWR drilling, etc. eliminate the need for oil imports? Considerably more likely.

The U.S. needs to do everything it can to develop domestic energy. The OCS and ANWR should be part of the overall solution.

Peter Schaeffer: I was merely assessing the proposition that has been made that drilling in OCS would drive down prices in a noticeable manner — no more, no less. The assessment for whether to exploit these resources now, and in what fashion, necessarily requires a much longer post, or preferably a full-fledged analytical study, wherein one tabulated risks and probabilities, and was straightforward about the weights attributed to consumers, producers, etc. By the way, I have not argued for the need to eliminate oil imports; perhaps that is in your objective function — but that merely highlights the fact that any given policy prescription is driven in large part by objectives.

Peter Schaeffer: By the way, your 1mbd figure for ANWR production is above the mean estimate recently released by EIA (May 2008), and halfway between the mean and high forecast. See this post for the references.

Menzie Chinn,

Sorry about the awful formatting in my first post. Please delete the duplicate version of this post.

I agree that OCS development will not have any immediate impact on oil prices. However, the combined output from aggressive development of lower-48 OCS oil / gas, offshore Alaskan oil / gas, and the ANWR could be material with respect to U.S. imports and oil prices over the next few decades. ANWR/OCS development could also raise GDP to a measurable extent.

Let me try to provide some hopefully germane statistics. A U.S. MMS report “Assessment of Undiscovered Technically Recoverable Oil and Gas Resources of the Nation’s Outer Continental Shelf, 2006” (http://www.mms.gov/revaldiv/PDFs/2006NationalAssessmentBrochure.pdf) provides all sorts of data on OCS reserves, resources, etc. The mean estimate of UTRR (Undiscovered Technically Recoverable Resources) on the OCS is 85.88 billion barrels. Of this, 41.04 billion barrels is in areas that are open for development, including the Western and Central Gulf of Mexico (GOM). Another 44.84 billion barrels are in areas currently closed to development, including the Atlantic OCS, Pacific OCS, Eastern GOM, and Alaskan OCS.

The situation in Alaska is actually more complex because some portions of the Alaskan OCS are not formally closed to development. However, they have not been leased, much less authorized for development to date. Indeed, the only portion of the Alaskan OCS clearly open for development is the Beaufort Sea. For purposes of this post, I will treat the Alaskan OCS as a closed area.

The closed OCS areas have total UTRR’s that are larger than the Western and Central GOM. The W/C GOM produced 1.34 MBD of oil (plus large quantities of natural gas) in 2007 (see http://www.mms.gov/stats/PDFs/AnnualProductionChartsFederalOCSOilandCondensate06-08.pdf for the data). This gives you some idea of the potential output of the currently closed OCS areas. Based on these numbers, future production of 1 MBD from the closed portions of the OCS (including Alaska) does not appear to be unrealistic.

Note that to some extent this is an apples and oranges comparison / model. The total GOM endowment (original oil resources before any production) is estimated at 71.91 billion barrels out of a total of 115.43 billion barrels for the entire OCS. It could be argued that the original endowment ratios should be used to estimate future potential production. This approach produces estimated future production of 0.8 MBD from the closed areas of the OCS.

Conversely, the GOM is already somewhat depleted (and the closed areas “fresher”). This implies that original endowment ratios may understate future production from the closed portions of the OCS.

A 2004 report on the ANWR (see http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/servicerpt/ogp/results.html) gives a mean estimate of peak production of 0.876 MBD (not 1 MBD as I stated). The high estimate is 1.595 MBD. Averaging the mean and high estimates gives 1.2355 MBD. For reasons that are not stated a 2008 ANWR report gives mean peak production of 0.780 MBD.

An important note is that these numbers could well be serious underestimates. The same report states that the estimated oil price in 2025 is $27 barrel in 2002 dollars. Obviously, a higher future projected oil price would raise low/mean/high estimates of future ANWR oil production considerably and further increase

Based on the above numbers the combination of the ANWR and the closed areas of the OCS could produce 2 MBD in the future. Using your estimates of the elasticity of oil supply and demand, that appears to convert to a 3.3% reduction in future prices (assuming flat world oil production going forwards…). If world oil production declines over the next 2-3 decades, then 2 MBD will be a greater fraction of total world oil production and the impact on prices commensurately greater. Of course, in a declining world oil production scenario oil prices are likely to be higher, making production above 2 MBD from the closed OCS/ANWR more likely and the price impact greater still.

Of course, the future benefits of 2 MBD of incremental oil production are not limited to lower prices. 2 MBD would raise GDP (by how much depends on future prices) and back out a material fraction of projected future U.S. oil imports. To provide some perspective, current total oil consumption is roughly 20 MBD.

Peter Schaeffer: Point of clarification: Are you using a long run supply elasticity of 3 or 0.3?

Peter Schaeffer,

Current US consumption is ~20 MBD. What counts is world consumption, which is more than four times that rate and climbing fast.

The 2 MBD increase that you are talking about is a peak, and a rather short-lived one at that. All of the data I’ve seen (e.g., Prof Kaufman’s charts) show a slow build-up that takes about 10-15 years to reach peak production, a few years of high production and then a very sharp drop-off.

2slugbaits,

You are correct in suggesting that world consumption is 4x the U.S. However, the rising fast part is wrong. World oil demand rose by 2.7 MBD from 2003 to 2004. By contrast, demand growth from 2006 to 2007 was only 0.84 MBD. So far demand growth in 2008 (versus 2007) has been negative. See http://www.eia.doe.gov/ipm/demand.html for the source data.

Note that in my earlier post I used world oil supply / demand to estimate the potential price impact of an incremental 2 MBD of OCS / ANWR production. Hopefully I was successful in applying the formulas provided by Menzie Chinn in other posts.

The suggestion that ANWR / closed OCS production will peak and fall off may or may not be correct. Note that the MMS is projecting considerable production growth from the Western / Central GOM even though these regions have been exploited for more than 50 years.

Given that the (UTRR + known reserves) / current production ratio for the W/C GOM is over 100, that is not entirely surprising. See http://www.flickr.com/photos/peter_schaeffer/2791215307/ for a chart from the MMS.

Given that the closed OCS (including offshore Alaska) has 44.84 billion barrels of UTRR, a 1 MBD production rate is less than 1% per year. At that level of exploitation, production might be sustained for a long time (as it has been in the W/C GOM).

Once again I would emphasize that all of these numbers are estimates and are dependent on unknown geology and future prices. If energy prices rise in the future, then the OCS / ANWR production numbers may be prove to be underestimates which would increase the economic gains from OCS / ANWR development.

Menzie Chinn,

I have tried to use the same long run supply / demand elasticities that you applied above. In your original post you wrote

“Substituting in some parameter values, taking Δa1 as the percentage increase in supply, namely 0.164% (0.00164), and setting the price elasticity of demand equal to -0.4, and and price elasticity of supply to 0.3 (Perloff and Whaples has cited these figures; plausible alternative parameter values would not alter the results in a qualitative fashion) yields the following: The resulting change from baseline in 2030 is -0.00234 (-0.23%). Taking the AEO 2008 baseline estimate of 70.45 2006$/barrel in 2030, the implied reduction in price is 0.165 2006$.”

I have assumed an incremental 2 MBD and production of 84 MBD. This gives a percentage increase in supply of 2.38%. Applying the ratio of 0.00234 / 0.00164 to a 2.38% increase in production gives a price impact of 3.39% (assumming I have applied the formulas correctly).