One measure that is being used to summarize the strain in financial markets is the TED spread. This is calculated as the gap between 3-month LIBOR (an average of interest rates offered in the London interbank market for 3-month dollar-denominated loans) and the 3-month Treasury bill rate. The size of this gap presumably reflects some sort of risk or liquidity premium. I was interested to break the TED spread down into identifiable components to try to get a better understanding of what may be responsible for its recent behavior.

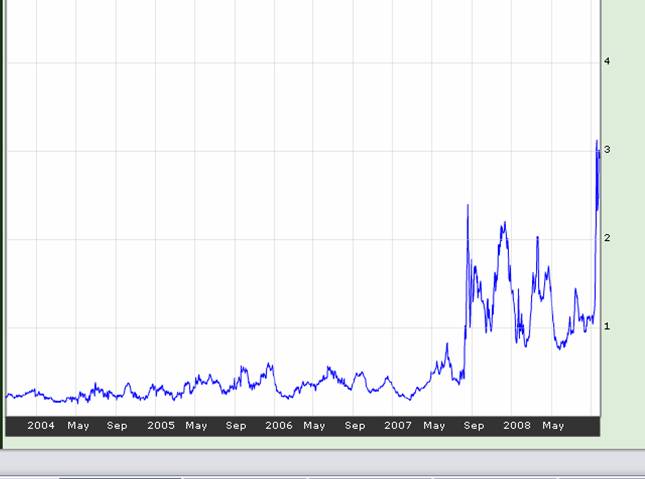

The TED spread over the last 5 years is plotted below; for a longer time series see Bespoke Investment Group. Historically the spread typically stayed under 50 basis points. However, it’s usually been above 100 basis points since the credit events of August 2007, and reached 300 several times during the last two weeks.

|

The overnight interest rate on loans between banks in the U.S. money market is the fed funds rate, whose average value is set as the primary target of U.S. monetary policy. There is also an overnight LIBOR rate, whose borrowers and lenders include some of the same banks that participate in the U.S. federal funds market, albeit a little earlier in the day. As a first step to understanding the LIBOR-TBILL spread, I was curious to look at the difference between the overnight LIBOR rate and the fed funds target. This had a rather impressive spike September 16-17.

|

Why would a bank want to borrow overnight dollars for 5-6% in London when it could be assured of obtaining those same funds for 2% later that day in New York? For one thing, the situation was sufficiently chaotic two weeks ago that many banks in fact were unable to borrow in New York at 2%. The effective fed funds rate (a volume-weighted average of all the known U.S. trades on a given day) was 2.64% on Sept 15 and 2.80% on Sept 17, despite the Fed’s intention to keep these numbers around 2.0. Somebody who was worried about how these days were going to unfold may have quite rationally bid quite a bit to secure the funds early. Or perhaps the U.S. banks dropped out of the London market altogether. In any case, a one- or two-day spike in this overnight rate is not that big a deal, since even a few hundred basis points (at an annual rate) is not that much money on a one-day loan. Following that impressive but brief spike, overnight LIBOR is now back to 2.31%, a modest 31 basis points over the Fed’s target.

One can break the TED spread down into separate components using the following accounting identity. Let LIBOR3 denote the 3-month LIBOR rate, LIBOR0 the overnight rate, TARGET the fed funds target, and TBILL the 3-month Treasury bill rate. The TED spread is defined as

TED = (LIBOR3 – TBILL)

which can be rewritten as

(LIBOR3 – TBILL) = (LIBOR3 – LIBOR0) + (LIBOR0 – TARGET) + (TARGET – TBILL)

As just discussed, the middle term above, LIBOR0 – TARGET, is at the time of this writing back to usual values, so the bloated value for the TED spread must be coming from a combination of the first and last terms. Indeed on Friday, the spread between the 3-month and overnight LIBOR rate stood at 145 basis points:

(LIBOR3 – LIBOR0) = 1.45

Why is the 3-month rate so much higher than the overnight rate? It certainly can’t be an expectation that the Fed’s target for the overnight fed funds rate is about to increase. If the Fed makes a move over the next 3 months (and it very well could), it would be for a decrease, not an increase, in the target. The LIBOR term spread must therefore be interpreted as some sort of a liquidity or risk premium. If I lend you funds overnight, I should have a pretty good idea of whether there’s some news coming within the next 24 hours that would prevent you from repaying. I may correctly judge that risk to be small. But over the next 3 months, who knows what might happen? If I were a risk-neutral lender, and I thought there was a 0.36% chance that a currently sound bank may go completely bankrupt over the next 90 days, I’d want a 145-basis point (annual rate) premium on the 3-month loan as compensation. If I were risk averse, I would require that 145-basis-point compensation even with a much lower probability of default.

Or, it may be that I’m afraid I myself might be exposed to some severe credit event over the next 3 months, and would be better off keeping any extra cash in Treasuries rather than lending them 3 months unsecured. I would describe this consideration as a “liquidity premium” as opposed to a “risk premium”.

If leading financial institutions are making these sorts of assessments of the probabilities of risk or liquidity needs, it bespeaks a very unsettled financial market that is apt to function poorly at channeling funds to any of the other inherently risky economic investments whose funding is vital for a functioning economy.

But this risk/liquidity premium only accounts for half of the TED spread. The remainder is due to the gap between the fed funds target (currently 2.0%) and the yield on 3-month Treasuries (now under 1%). This is the other part of the “flight to quality” just discussed. But on the other hand, the (TARGET – TBILL) gap is also a deliberate choice of policy. The Fed could simply lower its target for the fed funds rate, and chase the T-bill rate down to zero, if it wanted.

What’s the downside to that? Here’s the next shoe that could drop: the financial dislocations could lead to a perception by global investors that the U.S. is no longer a safe place to be putting their capital, which could add a currency crisis component to the present financial turmoil. Greg Mankiw notes this report:

China’s government moved to calm financial markets Thursday and denied a report that it had ordered mainland banks to curb lending to U.S. banks, a day after rumors of financial stability led to a run on a Hong Kong institution.

Calm again for the time being, I guess. But if a cut in the fed funds rate leads to rapid dollar depreciation and commodity inflation, it could be pulling the trigger on something even scarier than what we’ve seen so far.

Not an attractive set of options on the menu for the FOMC.

Bailout: The Final Bill

Bailout: The Final Bill I don’t think our Congress has faced a more important decision than whether or not to pass the bailout bill in decades, perhaps longer. (Summary here; CBO analysis here.) To state what is beyond obvious: it…

“There is also an overnight LIBOR rate, whose borrowers and lenders include some of the same banks that participate in the U.S. federal funds market, albeit a little earlier in the day.”

It is 8:40 am here in the Eastern Time zone. I doubt that the trading desks are open yet. It is 1:40 pm in London. Wouldn’t the sequence be the other way round?

I have been calculating the TED spread using the rate on Eurodollar deposits, since it is readily available on the Federal Reserve website. Would anyone happen to know where daily LIBOR historical rates can be found?

Thanks

excellent points

Nice analysis. Have a look at John Taylor and John Williams April 08 paper, “A Black Swan in the Money Market” (SF FRB working paper). Similar conclusion, and a pretty clever analysis. They found that counter party risk appears to be the most significant factor behind the blowout of spreads.

@GWG:

http://www.economagic.com/libor.htm

In the link to a longer view, going back to 1986, what stands out is that the TED spread is not a useful leading indicator of recession. It was not wide before the 2001 recession, for example, but it was very wide in September 1987, December 1994 and now.

When the spread widens because T-bills drop to near-zero, as is the case today, that does not mean the other end of the spread is high enough to cause trouble for the real economy. Interest rates alone predict well, but spreads apparently do not. Which is to say that financial strains like October 19, 1987 are not necessarily the same as real strains (contrary to many bankers).

In general, quality spreads are concurrent not leading indicators.

It’s 3.5 now

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/quote?ticker=.TEDSP:IND

I interpret this differently. It’s true that banks are fearful of lending to each other for the reasons you mention. However, the Federal Reserve’s daily commercial paper releases at

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/cp/default.htm

show pretty clearly that nonfinancial companies are able to borrow at low rates.

As Felix Salmon and others have pointed out, the huge expansion of Federal Reserve lending of both cash and Treasuries at various maturities means that a lot of banks’ funding needs are being met that way, rather than by interbank borrowing. When there’s little or no interbank borrowing, LIBOR doesn’t really indicate much of anything, as it’s merely an average of what banks say they would lend at, even when they’re not actually doing so.

I have read in various places that many contracts are specified in terms of a spread over (or under) LIBOR, so it may have some effect there. But it would seem that, if LIBOR behaves in such as way as to make those contracts no longer a good representation of the intent of the parties, the contracts will be changed to some other spread. In the age of word processors, it’s not that hard to do.

“it could be pulling the trigger on something even scarier than what we’ve seen so far.”

James,

This is too vague a statement – What do you mean ? People/politicians desperately need to be informed what the severity of the situation really is!

In the last week, America has been paralysed by debate about a baliout – meanwhile a fire was raging on Wall Street! This morning a couple more major institutions are gone and a watered down bailout goes to a vote – a baliout that might have been adequate over a week ago when it was desperately proposed but now even more buildings are on fire. This bailout may not be even enough to stem the worsening conflagration (can it still realistically be called a bailout anymore or is it now a token offering, “well, at least we belatedly tried to save eveyone”, as the whole city burns down.

Thank you for insights – but what do you mean by “even scarier” and have you, as an expert, made it clear to your elected officials what you think could happen? Are we making a serious effort to put out this fire – or is this baliout a copout?

Please academics – don’t watch and analyze and call plays from the sidelines – get out there in centre field – make a call (as hard as that can be without all the facts) and give Team America some help!!!

GWG asked: “I have been calculating the TED spread using the rate on Eurodollar deposits, since it is readily available on the Federal Reserve website. Would anyone happen to know where daily LIBOR historical rates can be found?”

http://mortgage-x.com/general/indexes/wsj_libor_history.asp?y=2008

Sebastian

James,

What I mean is this you trusted folks should inform the people everywhere who say “to hell with those greedy bankers – forget any kind of bailout!” of the possible or probable consequences.

The kind of people who don’t live on Main Street and think this fire is just what those Banker B%$tards deserve.”

The kind of ordinary rubber-necking gawking folks watching the entire main street on fire but who haven’t yet realized that once the fire department is ovewhelmed then the whole city (and their home too) will be threatened.

Forgive the hyperbole but I think ordinary folks really do not yet realize the seriousness of the situation – or why else would Amercia waste a week just to allow pompous politicians to “grandstand” while there is a huge fire gaining momentum.

There’s a simple way to solve the money market crisis: Admit that the market is collapsing and deal with that fact rather than trying to stop a force of nature. Let the money markets go. Recognize that the commercial paper ends up as a bank liability — financial paper for obvious reasons and non-financial paper because of bank backstops.

All Congress needs to do is extend FDIC insurance to all bank deposits that are in the bank as of close of business on Friday October 3. Support for money market funds should be withdrawn. The flow of money to the banks will avert the current crisis. Either the Fed, the Treasury or the banks will have to provide 3 months of collateralized loans to the money market funds to assist them in closing down.

In short, the government should be accelerating the movement of the money market funds into bank accounts to solve the crisis. This huge flow of liquidity will reopen interbank markets. After this process is completed, the FDIC can handle bank failures by shafting shareholders and bondholders, before taking losses.

I hereby declare a very attractive entry point for stocks. S&P500 at 1110. I stand by it.

I would go long on IWN and XLF, at this time.

JDH, thanks for an insightful analysis.

“something even scarier than what we’ve seen so far.”

The “pulling the trigger” decision for the FOMC seems to have the barrel pointed in two directions. A drop in the funds rate has the risk of adding a currency dimension to the crisis. Leaving the Fed funds rate constant currently tends to generate a high LIBOR, per your analysis. Many variable mortgages are linked to LIBOR and will reset to much higher mortgage rates, so the default problems continue/increase.

This is a very good article. However, I question whether the (LIBOR3 – LIBOR0) spread is a risk premium. Say that a given borrower has an equal probability of failing each day for the next 90 days. As a lender, I need (roughly) equal compensation for the default risk, for each day. In other words, the interest rate risk premium should be the same for 1 night versus 90. Why? Because over 90 days the risk is 90 times greater but so is my incremental return.

This is not quite right. But the point should be clear. As long as the implied per-night default risk does not rise sharply over time, the risk premium should not rise sharply either.

Very good decomposition.

One point:

“Why would a bank want to borrow overnight dollars for 5-6% in London when it could be assured of obtaining those same funds for 2% later that day in New York?”

I don’t think London branches of US banks can borrow directly in the Fed funds market, and I think their New York operations may have regulatory constraints on the amount they can downstream.

Fat Man: I intended the clause “earlier in the day” to apply to LIBOR, though I can see that the wording was ambiguous.

Anon at September 29, 2008 08:47 AM: By “something scarier” I refer to the scenario I sketch of a panic flight from the dollar, which I am worried might be precipitated by a sharp cut in the fed funds target. But the same could happen anyway without a cut in the target, just as the financial disaster many of us are worried about could happen whether or not Congress passes the $700 billion bailout plan. Without the plan, the financial disaster is more likely. Without the rate cut, the financial disaster is more likely but the currency crisis is less likely. I’m not offering more strongly worded advice to policy makers because it looks like a pretty tough spot we’ve gotten ourselves into. If I saw something I was sure would or wouldn’t work, I’d certainly say so.

Peter Schaeffer: Note these overnight rates are quoted at an annual rate, so they already include the cumulative risk of rolling over 24-hour loans. But you’re exposed to less total risk when you roll over 24-hour loans for 90 days than if you lend outright for 90 days, because in the former case you always have the option of stopping the rollover as news of your counterparty’s weakness arrives. These failures don’t happen out of the blue overnight.

“These failures don’t happen out of the blue overnight.”

JDH, your (and Menzie’s) economics blog is a favorite, but I read many others including Calculated Risk, Greg Mankiw, ect.

The statement ‘these failures don’t happen over night’ is appealing, but why was I not reading about the immediacy of the need (treasury secretary’s want) for nearly a trillion dollar emergency plan until a week before it was ‘needed’?

Most recent articles seemed to support or deny the occurrence of recession in 2008, debate its starting point, project its length, and so on. How low will housing fall, how far will the dollar value shrink.

Could it be that nobody knew such a large action would be ‘needed’ so fast, or was it known but hidden, or is it a political beast hatched from smaller need? Were there shocking discoveries in the secret books of Fereddie and Fannie? I do not understand how the treasury secretary could demand so much with so little notice.

What’s the Next Move?

Following yesterday's bipartisan defeat (subscription req'd) of the Emergency Economic Stability

“As I tell many audiences, the FOMC targets the federal funds rate, nominally the rate banks charge each other on overnight loans of deposits at the Fed. In fact, what the NY Open market Desk sets each day is the one-day repo rate on Treasuries, that is, the one-day cost-of-carry on government bonds. This is the true policy instrument — and it affects huge amounts of money (essentially, the one-day return on all government securities), while fed funds transactions daily, in comparison, are a trivial amount. Folks who actually deal in money markets know this; others usually do not.”

rga

Richard G Anderson

Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

Since John Maynard Keynes General Theory, economists have allowed bankers to buy their liquidity, whereas historically bankers stored their liquidity. And it’s hypocritical, as the bankers (as a system)are paying for deposits they already own. Thus the LIBOR rate is a pseudo-economic anomaly. The proper public policy is to get the commercial banks out of the savings business (but not the non-banks).

I heard this on the radio (NPR) a few days ago:

‘the amount of money in the world doubled in the last six years, but the availability of worthwhile investments did not increase’

Is it true? Where is it coming from? And how?

Is this like the old joke, ‘Gentlemen, somewhere in the world, every three seconds, a woman has a baby — our task is to find this woman and stop her!”?

“If I lend you funds overnight, I should have a pretty good idea of whether there’s some news coming within the next 24 hours that would prevent you from repaying. I may correctly judge that risk to be small. But over the next 3 months, who knows what might happen? If I were a risk-neutral lender, and I thought there was a 0.36% chance that a currently sound bank may go completely bankrupt over the next 90 days, I’d want a 145-basis point (annual rate) premium on the 3-month loan as compensation. If I were risk averse, I would require that 145-basis-point compensation

even with a much lower probability of default.”

I tried to check this in Excel and I believe this assumes a recovery rate on the lending of zero. My understanding is that most CDS have a recovery rate of 40% built into them. That suggests that the probability of default was more like .6% which is even higher. This implies a default rate worse than a single B credit rating. Wow.

Me the quote:

‘the amount of money in the world doubled in the last six years, but the availability of worthwhile investments did not increase’

Is information from the IMF that stated that all the worlds savings have doubled since 2000 to over 70 trillion.

The interview was conducted as part of a joint story for This American Life and NPR news. The TAL episode is called “Giant Pool of Money” and the basic premise is that as wealth increased and Greenspan and other Central banks kept interest rates low longer than they should have it drove investment to higher yielding supposedly AAA securities i.e. MBS’s.

At the time people thought that these WERE the worthwhile investments that could meet the demands of all this money. Most people were wrond and now have alot of toxic trash.

I thought about the T-Bill rate and that you possibly take in a liquidity premium (it can be bought and sold at all times) and at current maybe a supply-side premium into the equation. Hence, when using a repo rate (which has minimized credit risk due to collateralization -if it can be found-) the counterparty risk premium can possibly be extrapolated more accurate.

With the repo rate, the last term (Target-Repo) transforms from a “flight to quality” into a proxy for the expectation or term structure effect (since if the spread is positive, an easing is expected). Using that, one can possibly better get an idea about the actual liquidity effect from default over time or a fund squeeze from the (LIBOR3-LIBOR0).

Why isn’t the spike in this spread being reflected in overall commercial bank lending flow activity, based on Fed data? See http://www.cato.org/pub_display.php?pub_id=9685 .

GWG — The best source for LIBOR rates is the British Bankers Association, which has Excel files available for download: http://www.bba.org.uk/bba/jsp/polopoly.jsp?d=141&a=627

As Mike mentioned, it seems like one of the larger issues with LIBOR, regardless of its role as in indicator, per se, is the fact that so many loans in the US are tied to LIBOR rates. These loans seem to have frequent reset rates as well. Given the role foreclosures, etc. have played in the current market crises around the world, high and fluctuating LIBOR rates have ripple effects throughout the economy.

I am curious, however, to know how reliable the LIBOR is based on a few articles that noted the possibility of banks understating their overnight rates. What would the benefit be to the bank in the long run, and doesn’t this undermine the point of the rate?

Hey, GK, you’re the man! Got any other great pontifications for us to short?

>I hereby declare a very attractive entry point for stocks. S&P500 at 1110. I stand by it.

>I would go long on IWN and XLF, at this time.

>Posted by: GK at September 29, 2008 02:29 PM

LIBOR OIS & TED spreads ended the week down 21% and 27%

CP Yields on 90day paper increased to 4.9% on Firday, posting a 14% decrease for the week

5 year spreads on A-rated corporate bond increasing 4.9% and B-rated bonds increased 3.7% for the week.