The OECD has just released its forecasts. This follows the recent updated IMF forecasts. Growth is evaporating the industrial countries. What is to be done?

Figure 1: From visualization of OECD Economic Outlook 84 [link]. Blue is negative growth (for 2009), darkest blue is -9.335%; orange is positive growth, most orange is +9.335%. White is zero; gray is “no forecast”.

Table from press conference for the release of OECD Economic Outlook 84 (25 November 2008).

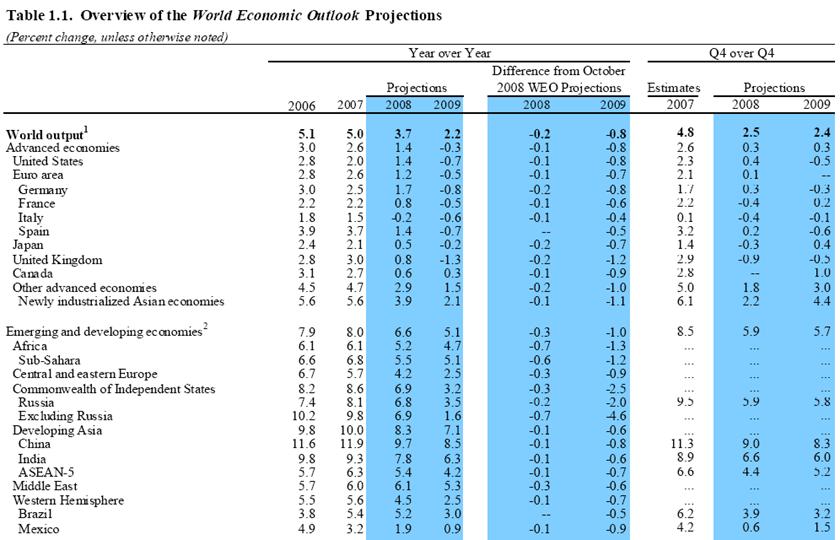

Table from IMF WEO Update (November 6, 2008).

With the industrial economies, representing a very large chunk of world GDP, all colored varying shades of blue and entering a period of slowdown, it seems like we need to think not only about macro policy in the US, but also abroad (and what those policies mean for the US).

There is a distinct advantage to the United States advocating expansionary fiscal policy in our trading partners. The way to think about this is to contrast the closed economy multiplier with the open economy multiplier. Consider the closed economy multiplier first:

ΔY/ΔG = 1/(1-c(1-t))

where c is the marginal propensity to consume, t is the marginal tax rate. I assume no transactions or portfolio crowding out of investment and hence output.

As I’ve noted before, when there are slack resources available in the economy, a dollar’s worth of government expenditure is “multiplied” by repeated rounds of income-spending-income-spending, so that the end impact is greater than that initial dollar’s worth of government spending.

However in an open economy, that multiplier effect is diminished by the fact that some spending “leaks out” in the form of imports. That is, some of the incremental spending is on imports, which then become income for our trading partners since their exports rise. There is some repercussion effect since then our trading partners income will rise pulling along their imports — our exports to a certain extent. So now consider the open economy multiplier in a small economy:

ΔY/ΔG = 1/(1-c(1-t)+m)

Where m is the marginal propensity to import. A naive regression tells me this number is around 0.2. Allowing a repercussion effect (as discussed in this post — so assuming a large economy) pulls up the multiplier a bit:

ΔY/ΔG = 1/(1-c(1-t)+[(m*m)/(1-c*(1-t*))])

Where m*, c*, t* are the corresponding foreign country parameters, if one can think of the economies as symmetric (e.g., US vs. euro area).

The OECD multipliers I discussed in this post assume this repercussion effect.

Table A1: “Government Spending” from Thomas Dalsgaard, Christophe Andre and Pete Richardson, “Standard Shocks in the OECD Interlink Model,” OECD Economics Dept. Working Paper No. 306.

Table A4: “Tax Cut” from Thomas Dalsgaard, Christophe Andre and Pete Richardson, “Standard Shocks in the OECD Interlink Model,” OECD Economics Dept. Working Paper No. 306.

In the OECD’s Interlink model, they don’t look altogether that large. However, recall that while the multiplier is 1.1 in the 1st year out for a fiscal impulse of 1 ppt of GDP, it’s 1 in the first year and still positive in the 3rd and 4th years out. So the sum effect is substantially greater than unity.

Now, if all the countries (or all the relevant countries) were to stimulate simultaneously, then the aggregate world economy would look a lot more like a closed economy, and the multiplier would be larger yet again.

I suspect that policymakers do not need to much additional encouragement. After all, stimulus packages have been announced in Europe [1], UK [2], Japan as well as China (summary see [3]). On the other hand, there might be some anxiety about expanding government debt given long term entitlement/pension/health care funding issues in Europe and Japan, as well as in the US. I think there’s good reason to worry, but those are longer term concerns, and as long as we can anchor expectations about long term deficit reduction, then deficit spending now is less problematic (although, as I mentioned in my discussion on MPR today, we are more constrained exactly because of the profligacy of the Bush ’01 and ’03 tax cuts). We are aided in a sense by the likelihood that all the industrial countries are likely to engage in substantial deficit spending, thereby mitigating the negative portfolio balance effects I’ve outlined before.

Hence, to the extent that these are “real” stimulus packages (for instance, there is substantial discussion that the fiscal element in China’s package is not anywhere as big as appears from first reading [4]), the impact of a synchronized fiscal expansion will be bigger than the one would expect from the standard estimates.

What about expansionary monetary policy? Here I have two observations. The first is that as we (in the US) have come to effectively zero policy rates, we have the odd situation that many of the recently estimated multipliers are no longer applicable. As a consequence, I’ve started looking at old-style monetary policy multipliers that relate output changes to changes in money stock (these are the kind that we used to teach in intermediate macro, but have been out of favor since at least the first sighting of the “Taylor rule”. Those interested in some open economy monetary policy multipliers can see this insightful article from Frankel and Rockett (1986). The second observation is that expansionary monetary policy (in usual times) would tend to depreciate currencies, but has ambiguous impacts on the current account. Hence, I would not make too big of an issue about competitive devaluations as a means toward expenditure switching.

By the way, conceptually, protectionism is a way to increase the size of the multipliers, if one focuses on the single-country open economy multipliers — just think about how protectionism could reduce the parameter m. But once one thinks about retaliation — in the context of the two-country multiplier, one can see this is a truly counter-productive policy.

What does the foregoing imply for policy? First, assume the forecasters from the Wall Street Journal survey are (on average) correct, then the US output gap in 09Q4 will be about 5.5% in log terms.

Figure 2: Log real GDP, from 26 Sep 08 final release (red), and from 30 Oct 08 advance release (blue), potential GDP (black), WSJ mean forecast from October survey (pink circle), from November survey (teal triangle). Source: BEA NIPA releases [link], CBO estimates of 9 Sep 08 [xls], WSJ survey of forecasters from October and November [link].

Second, assume the multipliers are somewhere between those in Table A1 and Economy.com’s infrastructure multipliers shown in this post (say about 1.35 one year out).

Then a stimulus of about 4 ppts of GDP — roughly $580 billion — will bring output up to about potential. The bigger the tax cut element skewed toward higher income deciles, the larger the required stimulus. (However, I’m optimistic that with the new economic team of Summers, Orszag, Romer and Geithner that’s been selected, the package will indeed hew to the idea of maximizing the stimulative impact, which is consistent with targeting the lowest and middle income groups for tax cuts/rebates [5], [6].)

And if stimulus across countries can be synchronized, then so much the better (especially since it would be hard to spend at $580 billion in one year).

By the way, the reason why I don’t say “coordinated fiscal policy” is because, in the lexicon of academic economists, this would mean commitment to some sort of rules so that Nash outcomes can be avoided. See Frankel and Rockett (1986). In this discussion, I have in mind a more modest, one-shot, event, since I’m not sure a coordination is feasible over the longer term.

On a side note, I’ve just been watching Nancy Pfotenhauer on Larry King characterizing the new Obama economic team as “not change” because they are centrists. I think she misses the point entirely (not surprising). The “change” is not a matter of the economic ideology of the new team members — rather the “change” is bringing in people who value expertise and evidence-based policymaking over ideology and dogma. That is, the end of PoMo Macro policymaking.

Technorati Tags: multipliers, fiscal stimulus,

fiscal policy, recession, infrastructure, tax cuts, output gap,

and portfolio balance.

I assume no transactions or portfolio crowding out of investment and hence output.

Please note the fine print, readers. It’s really important sometimes. In Japan’s experience, spending beyond a point is a net detriment to output. I strongly suspect that for some of the economies in the survey, like the U.S., this will be operative. I strongly suspect that for others, like India and China, where debt-to-GDP is closer to 60% and savings rates are much higher, Keynesian stimulus is precisely the right choice.

Menzie, are you not concerned about the quality of the consolidated balance sheet of the central banks, particularly the ECB? Is that simply a problem to be considered later?

Also, let’s imagine we are successful in reigniting inflation through this fiscal stimulus. How would you slow it down once it’s started? We would normally sell treasury bonds from the Fed’s balance sheet, but it doesn’t have very many of those anymore. We could stop repos, but that would destroy the bank on the receiving end.

Iceland is definitely in a deep blue funk. And at first glance I thought Finland had joined Team Blue but a second look reveals a very light shade of orange.

Menzie,

I understand how govt debt could be a problem under a gold standard, but what is the difference under our current floating rate policy? The interest paid on the debt is just a circular flow from taxpayer to bondholder and leaves the total money in the private sector unchanged. The interest also consumes no REAL resources (labor or materials). And I believe the principle can be rolled over forever so it will never be a burden on future taxpayers.

The real economy is about the production of goods and services and the distribution and consumption of those goods and services. Future generations will produce and consume what they are capable of. How do present govt deficits effect future production? How future generation decide to divide up production between workers and retired people is up to them. Today’s govt deficits should not have any bearing on that decision. If anything, stimulating economic activity with deficit spending will lead to increased productivity making it easier for future generations to cope with supplying the health care, pension, entitlement spending. I am not saying “damn the deficit, full speed ahead”, but I do think sustained deficit spending in the area of 3-4% of gdp per year will lead to a smoothing of the business cycle which can only benefit future generations.

Dear All,

Defecit spending will do nothing to soften the blow. In fact, it will greatly enhance our difficulties. Markq is correct. Interest rates do not consume real resources like labor and capital. But this ignores the importance of the crowding out effect. With such massive outlays coordinated with a dearth of investment grade assets, the destruction of our credit generation machine and drying up of liquidity investors are piling into treasuries. Note the 30 year approaching 120 with an implied rate of 3.62 pct. Demand is enormous at this point in time. Without a doubt this is pulling funding away from bank credit lines as the flight to “safety” has begun.

But fear is growing as the amount of government is borrowing is greatly expanding. I’ve seen assumptions that interest payments alone may consume 25pct of the US govt outlays by 2012. Investors are beggining to look at bond assumptions models on their interest payments and getting spooked. Look at the CDS rates of 10yr treasuries approaching 56bps.

Am I implying that that some point the US government will default? No, but at some point investors will no longer purchase these notes at such low implied interest rates. Especially with an essentially naked credit default protection market. Increasing government rates will drive productive businesses to match them through their credit lines. With an unprecedented rf bond vs. junk bond spread already facing a number of businesses, how much will this blow out with government rates being pushed up? At what point do we see a serious decline (even nore than now) in business lending by banks (and thus increased fear of counterparty risk between businesses too, further halting business flows).

Without a doubt this will cause availible capital to businesses to fall even more substantially then it already has. Banks are taking, and will take, their capital injections and buy riskless assets. All types of delveraging investors are too. This is styming business lending. This will grow more as the government sucks in more private capital. Further exasperating of this will occur when treasury auction interest rates climb to reflect the new risk of its cash flows and its growing balance sheet. Thank God we didn’t start buying the illiquid CDOs, CDS and real estate backed garbage. Massive stimilus is terrifying. It would be deleterious to business financing and it must be avoided at all costs.

“With the industrial economies, representing a very large chunk of world GDP, all colored varying shades of blue and entering a period of slowdown, …”

Not Canada! (Well….not yet.)

RPB,

I’m in agreement with your scenario. Doesn’t this put cash-rich companies like MSFT in the driver’s seat?

“There is a distinct advantage to the United States advocating expansionary fiscal policy in our trading partners.”

ROTFL!

There is an even larger advantage in the rest of the world to advocating that the US undertake the expansionary policy. So let’s consider the implications of different assumptions for how other economies are likely to behave….

1) Other Governments are rational.

1A) If this is a one-shot game, everyone plays Nash. This leaves the largest economy with the choice of stimulating their economy and tolerating the resulting demand leakage and future tax burdens, or accepting the status quo ante. (Note that from a bargaining position, the aggressive commitment of US authorities to unilateral fiscal expansion have very effectively foreclosed any potential threats to forego deficit spending unless other countries co-operated.)

1B) Propose a repeated game in which the US Congress agrees to abide by multilateral rules for fiscal policy under which….(no point in finishing that sentence; it’s never going to happen.)

2) Foreign Governments are irrational.

This means that US diplomats would have to deal with the legacy of recent US unilateralism on a variety of issues (which could make US requests on this issue seem opportunistic), as well as possible recriminations portraying past US policies as the cause of the current problem. Neither would be conducive to success.

I am uncomfortable with the assumption that multipliers based on data showing past reality apply to tjhe U.S. economy today. If we really are in a totally new enviornment, we should be suspicious of rules derived from previous reality.

It is possible for stimuli not have the anticipated multiplier effect because the money provided in the past 3 months has gone to pay off old debts or is horded to improve the balance sheet. When these multipliers were calculated, more of the stimusli went to consumption. Can we reasonably assume that the multipliers apply to the the U.S. today?

Analogous argument applied to the assumption that protectionism will create retailation. Import restriction on individual products, such as sugar or steel, has created retailation in the past.

But if import restrictions are applied to all products from selected countries, based on the acceptance of equal trade as the legitimate goal for all trade policy for all nations, then we have a new intellectual framework and no justification for retailation.

Those of us who think the stimuli applied in the last few months and the next few months will not significantly change the downward spirial of the world economy are obligated to identify an alternative course of action.

Concentrate on reducing foreclosures, where such actions can benefit both investors and house occupants, without heavy governmental investment.

Reduction of monthly mortgage payments to 70% of current expenditures for a limited time – say three years – for a limited segment of the house occupants – would benefit both investors and those house occupants – if the house occupants could resume payments at the end of the three year period at the payment schedule specificed in the mortgage. Likely few house occupants could meet the requirements but it would be worth the trouble of seeking out these people and giving them the option of temporarily reduced payments.

The above suggestions rests on the assumption that house prices must stablize before the economy will cease declining and that reduction in foreclosuress is the fastest way to stabilize house prices (absent government purchases of houses, which is too much governmental intervention).

Those of us who think the stimuli applied in the last few months and the next few months will not significantly change the downward spirial of the world economy are obligated to identify an alternative course of action.

Concentrate on reducing foreclosures, where such actions can benefit both investors and house occupants, without heavy governmental investment.

Reduction of monthly mortgage payments to 70% of current expenditures for a limited time – say three years – for a limited segment of the house occupants – would benefit both investors and those house occupants – if the house occupants could resume payments at the end of the three year period at the payment schedule specificed in the mortgage. Likely few house occupants could meet the requirements but it would be worth the trouble of seeking out these people and giving them the option of temporarily reduced payments.

The above suggestions rests on the assumption that house prices must stablize before the economy will cease declining and that reduction in foreclosuress is the fastest way to stabilize house prices (absent government purchases of houses, which is too much governmental intervention).

If this is a one-shot game, everyone plays Nash.

The premise of capitalism is that the game is not one-shot nor zero-sum. I think that premise has a damn fine track record.

I am uncomfortable with the assumption that multipliers based on data showing past reality apply to tjhe U.S. economy today. If we really are in a totally new enviornment, we should be suspicious of rules derived from previous reality.

Me too. I think you have a lot of good points, ReformerRay. I just disagree that reduction of monthly mortgages payments is enough. We really do need principle reduction. Yes, it’s unfair, but someone has to get screwed at some point, because we’ve promised too much to ourselves.

I’d rather that not be the homeowner, and rents and pricing will adjust themselves to match in the event of downward adjustment of principle. Our entire point as housing bears is that fundamentals had been decoupled from pricing due to market insanity. Decoupling in the other direction would be just as bad.

ReformerRay has a great point with the multiplier assumption. I’m under the impression that the multiplier will be drastically lower for RR’s reasons, but also because the propensity to save increases if people face recession. I’ve seen good empirical evidence of it, but nothing really solid. Also remember that the driver of our growth, the consumer, is tapped out and the credit machine that enabled her has been largely eradicated.

KT Cat. If my scenario is correct than I beleve that would be the case. Either way, with the coming deflation-inflation cycle (infl coming from lack of reinvestment in all types of production and transportation capital) any company with solid cash could pick up assets at fire-sale prices. You’ll see evidence of this first in large dry bulk vessel sales from shipping company bankruptcies. Long term capital destruction is already occuring in oil, livestock and other commodities.

I know of one CEO, who I’ve personally worked for, that is poised to do this and has done it before in the past. His name is Nassef Sawiris and he runs Orascom Construction Industries in Egypt. Construction is just the title. He’ll take a look at any opportunity involving industrial assets like ports, ships, basic chemicals and steel production. Check out his background and you’ll understand why is tripled his wealth (to 11.9bn) this year.

I think RR is on to something. As far as solving the crisis, the solution is over my head. However, the system has a lot of implicit assumptions. But two are of paramount importance to banks: transparency and proper asset pricing. I do not know very much about the Crisis of 1907, but JP Morgan essentially had all the banks show him what was under their skirts and he then decided who would live and who would die. Unfortunately I do not believe that this is possible with the insane complexity of the system. Our current solutions are just treating the symptoms and making things worse.

Thanks for the “side note” at the end, Menzie, and esp the PoMo Macro link…somewhat inspiring.

ndk: I regarding your first comment, I don’t see how the transactions/portfolio crowding out assumption I made links to the Japanese case. I think the Japanese malaise has much more to do with the reluctance to let nonfinancial firms fail, and failure to inject sufficient capital, than overspending (speaking as a non-Japan expert, but somebody who participated in the research for the dialog between CEA and our Japanese counterparts).

Markg: You ask a big question, and I’ll direct you to the macroeconomics textbooks for the answer — but you can think about full-employment models wherein the government consumption reduces resources available to investment, and hence capital accumulation. Of course, once you depart from full employment, and have slack in the economy, then this “cost” disappears — as you indicate in your comment.

ReformerRay: Multipliers are estimated over sample periods encompassing recessions.

As one who does applied econometrics for a living, I share your skepticism, but what’s better?

Regarding homeowner relief, I believe this can be a useful adjunct to fiscal policy, but it won’t be sufficient. We have a credit crunch, a capital crunch, and a medium term process of deleveraging, all ongoing. Homeowner relief and rising housing prices will help along the first two dimensions, but not the last.

SvN: Still time before the stimulus program is passed. There are lots of estimates floating around, and the higher numbers are not a done deal. Remember, most discussions talk about spending distributed over two years. Hence, the US still has leverage. In addition, there can be leverage across issue-areas — trade (i.e., access to US markets) seems like one that will likely be exploited. Believe me, I think American policymakers can be clever enough to provide additional incentives to act…

Assuming the multipliers used by Menzie will be more accurate when the stimuli applied are not diverted to paying old debts or building up balance sheets, I still have not answered the question of how we get from here to there.

Suppose the government does exactly the opposite of Obama’s proposal – just humkers down and waits until things gets worse? Do we arrive at the point where so much wealth and capacity to produce goods and services is destroyed that resurgence is not possible? I hope not.

Maybe we need to study the question of who is profiting from the deleverage. As some become poorer, are some others becoming richer? Will the newly rich be able to start the economy again?

How can capacity to produce goods and services be preserved during the deleverage? If it cannot, perhaps those who argue for immediate action have the better of the argument.

I don’t see how the transactions/portfolio crowding out assumption I made links to the Japanese case.

Sorry, I think this is my terminology being bad. Let me try referring to Friedman as quoted by Werner, who said it better:

“The quantity theory implies that the effect of government deficits or surpluses depends critically on how they are financed. If a deficit is financed by borrowing from the public without an increase in the quantity of money, the direct expansionary effect of the excess of government spending over receipts will be offset to some extent, and possibly to a very great extent, by the indirect contractionary effect of the transfer of funds to the government through borrowing.”

Werner then goes on an extensive discussion of how to apply this in situations where velocity has declined. His empirical analysis of this model in part B matched against Japan’s ’90’s is more successful than Keynesian models.

I think the Japanese malaise has much more to do with the reluctance to let nonfinancial firms fail

The largest non-financial firm to fail in 2008 was Circuit City. We’ve propped up a large number of corporations from GE to GM. I don’t think we’re doing any better there.

Werner in the paper I linked: “What all these formulations (classical, Keynesian and post-Keynesian) have in common is that the ineffectiveness of fiscal policy is the result of increased interest rates…. The main problem with these interest-rate based arguments for fiscal policy ineffectiveness is that there is no empirical evidence in their support…. we find that short-term real interest rates fell from 4.2% on average in 1991 to 0.11% on average in 2000, while long-term real interest rates fell from 3.0% on average in 1991 to 0.7% in 1998.”

They may have fallen in Japan, but Japan had a very large current account surplus. We have a very large current account deficit. They’re definitely only rising here, thus far.

RPB, thanks for the reply.

ndk: The point is that Japan did not have well developed bankruptcy laws, and the availability of debtor-in-possession lending was constrained. That is different in the US case (in fact some have argued the US Chapter 11 reorganization laws are too easy). Now, with the financial system as stuck as it is now, I’m not sure how available DIP lending is now, especially for firms as large as GM, but at least the institution has been around for a long time.

I now understand the point you’re making re: portfolio crowding out. I think portfolio crowding out is possible, but not too likely in the next couple years, the international demand for Treasuries being larger than for JGBs during the 1990’s.

I now understand the point you’re making re: portfolio crowding out. I think portfolio crowding out is possible, but not too likely in the next couple years, the international demand for Treasuries being larger than for JGBs during the 1990’s.

Great, I’m thrilled it’s clear now, and sorry for my lack of formal training. Thanks for your patience, Menzie.

Re: international demand for treasuries, though, can that really take over? I don’t think it can, and neither does Michael Pettis. We would by definition have to begin running an even larger trade deficit, and that’s already huge relative to GDP…

Menzie;

It will be hard for US officials to make credible the claim that the size and nature of the stimulus program depends critically on international co-operation. Given the way that national legislatures work, this claim would be a tough sell in *any* G20 country (think of the French, to take just one example) but especially tough given the particularly “independent” streak of the US Congress.

If there is to be some other incentive, what would work? Do you think Congress would be willing to compromise on defense issues? Do you think they can be credibly less protectionist in a major recession under Democratic control? (Recall the flap during the Ohio primaries when Obama’s campaign had its credibility attacked on promises to “renegotiate” NAFTA.) I don’t think that there is any doubt that the US *could* find a way to motivate other industrial economies; I think the doubt about whether the US has the political will to do so.

SvN

Smells like hyperinflation.

ndk: Believe me when I say few people have worried about the implications of US budget deficits run over the past few years as much as I (see my 2005 CFR report for a whole 30 odd pages on the subject), but for the next couple years, I do not see portfolio crowding out as a problem, in part because of simultaneous borrowing needs of governments around the world, and because cyclically, demand for borrowing will be low by firms given investment prospects.

SvN: We’ll just have to wait and see how independent Congress is. I think the incoming administration has a lot of capital, and may prove more effective than you believe.

W.C. Varones: By hyperinflation, do you mean inflation in excess of 50% per month (a conventional economist’s definition)? If so, well, I can’t see it.

Believe me when I say few people have worried about the implications of US budget deficits run over the past few years as much as I

Yes, I’ve been a long-time follower and fan of the blog. 😀 I’m glad you were banging the drum, and very much regret it wasn’t heard. We’d have a lot more flexibility in policy now if we had been prudent then. We were in an extremely different credit and macro environment, and I strongly believe crowding out is actually a much greater threat now than it was during our credit creation heyday.

I do not see portfolio crowding out as a problem, in part because of simultaneous borrowing needs of governments around the world…

I disagree with this. To the extent they’re borrowing and spending on Keynesian stimulus, it would hopefully increase their domestic demand for goods and services to address some of their overcapacity issues. If it does, that should reduce their trade surplus, and hence their re-investable proceeds.

Also, there are also many countries(Russia, Korea, etc.) who have switched from net purchasers to net sellers of dollars as they defend their currencies.

… because cyclically, demand for borrowing will be low by firms given investment prospects.

Lower than it would have been, perhaps. But there are acute funding pressures and strains already. Real interest rates for corporations have spiked hard. IBM at T+388, AmEx becoming a bank for TARP, companies from Textron to Nissan to AEP to GE needing the Feds to buy their CP, and so on.

In a deflationary environment, even if they are on net paying off debt in nominal terms, their real burden could be growing. And, if that were the case, that’s deflationary too.

I think this is a severe issue that undermines any net benefits of fiscal stimulus entirely.

To the extent that crowding out is ameliorated by international debt sales, isn’t the effect of the stimulus lost to an increase in the CA deficit?

As for the effectiveness of the stimulus, isn’t it possible that cooperation in fiscal stimulus can be negated by uncooperative monetary policy behavior? For example, Japan and China may introduce fiscal stimulus, while at the same time China suppresses the renminbi with currency purchases and Japan encourages the yen carry trade with implicit promises to intervene in currency markets should the yen appreciate too abruptly. Isn’t it also possible that such policies would respond perversely to fiscal stimuluses that appear to ameliorate the downturn abroad?

On another note, could the failure of fiscal stimulus in Japan come from Ricardian neutrality? If so, such responses in the U.S. may be more muted, as income is distributed less evenly here, although U.S. lower-income taxpayers may end up bearing more of the future tax burden than they anticipate, because the high future burdens are likely to give rise to a U.S. consumption tax.

As for the effectiveness of the stimulus, isn’t it possible that cooperation in fiscal stimulus can be negated by uncooperative monetary policy behavior?

That’s one of Werner’s points, don, but monetary policy can’t be cooperative in the U.S. It’s impotent. The Fed’s balance sheet is already ruined, and both quantitative easing ($600B of excess reserves?) and Fed Funds Rates below the rate the Fed pays out on deposits.

On another note, could the failure of fiscal stimulus in Japan come from Ricardian neutrality?

Probably not. Personal savings rates have only fallen in Japan while these policies have been in place.

“As for the effectiveness of the stimulus, isn’t it possible that cooperation in fiscal stimulus can be negated by uncooperative monetary policy behavior?”

My point is a bit different from Werner’s, I think. I am concerned that Chinese monetary actions (currency interventions) can offset substantial fiscal stimulus by other countries. Brad Setser thinks China may accumulate $500 billion in foreign reserves in 2009, enough to offest fiscal stimulus of that amount in its trading partners.

Re: Ricardian neutrality – of course we would need to know the path of saving rates without the increased defcits: they might have declined by more.

My point is a bit different from Werner’s, I think. I am concerned that Chinese monetary actions (currency interventions) can offset substantial fiscal stimulus by other countries. Brad Setser thinks China may accumulate $500 billion in foreign reserves in 2009, enough to offest fiscal stimulus of that amount in its trading partners.

Oh. I thought you were referring to the U.S., because I’m bad at reading comprehension that early in the morning. Apparently, I’m bad at grammar too.

Domestic fiscal stimulus and continued downward monetary intervention seems to be a great way to boost domestic investment and suppress domestic consumption. Export markets appear more lucrative, and the government is eager to buy and improve commerce through further infrastructure development.

As to the effect on its trading partners, I don’t know. It funds the Treasury’s intervention and it puts more currency in the system, which would lessen the financial crisis. However, it makes NX worse. My guess is that it would tilt any resulting growth further towards government and consumption and away from investment.

It’s an interesting question, though. I need to think about it some more. What do you think the influence would be?

Re: Ricardian neutrality – of course we would need to know the path of saving rates without the increased defcits: they might have declined by more.

True that. At least in a lifecycle model, with Japan’s shrinking workforce, the savings rate would’ve probably declined anyway.

Oh Gadzooks. Between Setser and here, I think I see your point. Even if our domestic stimulus works, to the extent that China goes back to its familiar exports watering hole for growth, it’s counterproductive and only makes the external imbalances worse.

So, even if I’m wrong and this stimulus/Fed rescue plan does work, the most likely outcome by far is that our trade deficit gets worse, our consumption grows, and our investment decreases, while Chinese investment and holdings of our debt increase. In effect, we’ve done nothing but buy a little bit more time by significantly increasing our debt loads, particularly that of the Fed and Treasury.

Well, that’s another reason this stimulus idea sucks, and we have to focus on revaluation of the yuan, which brings its own set of calamities. Great.

If this is the conclusion you reached too, I’d urge you to spread the word.

Expanding on my last point, there are two immediate calamities for China that come with the revaluation of the yuan. The first is an immediate and dramatic decrease in export competitiveness, at a time when there are riots in toy factories and widespread closures of export firms. The second is the immediate write-down of the assets on the PBoC’s balance sheet by, say, 30%, which bankrupts it overnight. It would need to be recapitalized through a direct injection from the government on the order of 25-30% of GDP. Imagine, as an American, being told by Hank Paulson or Tim Geithner that your income taxes would be increased by 5% to pay off bad investments in Russia or China, at the same time that you just lost your job.

My hunch was always that they would revalue quietly through inflation, and make up the loss on seigniorage. Now it’s a virtual lock. So, here’s hoping that I’m wrong and portfolio crowding out is not an issue.

I’m a little bit confused by your post. As you reach the point in the post which shows the GDP potential graph, and you begin to talk about the assumptions one could make to get GDP back to normal, what is missing is the timeframe.

I liked the post, but if you read it through, you might want to flesh it out just a bit more.

Gregor: 4 ppts of GDP for one year would get US GDP up to potential in one year, given the multipliers cited. If that amount is distributed over two years, one would not hit potential. However, if there were a synchronized fiscal expansion — either intentionally or accidentally — then the one might get substantially closer to potential than would be guessed looking at open economy multipliers assuming no expansion abroad (i.e., the cited multipliers hold constant rest-of-world policies).

ndk: I understand your argument that combined portfolio and transactions crowding out could negate the fiscal impulse — see here. But transactions crowding out looks unlikely, and on the portfolio side, one needs to look at likely demand.