As we near the end of the year, and the end of eight years of Bush economic policy, I think it’s useful to look back. The White House has recently tangled with the NYT regarding what got us into the current economic crisis [0] (see also [1]). This comes on the heels of the Paulson argument that he would not have done anything different, had he known the full extent of the looming crisis. This leads me to wonder how we should view the Bush Administration’s stewardship of the economy.

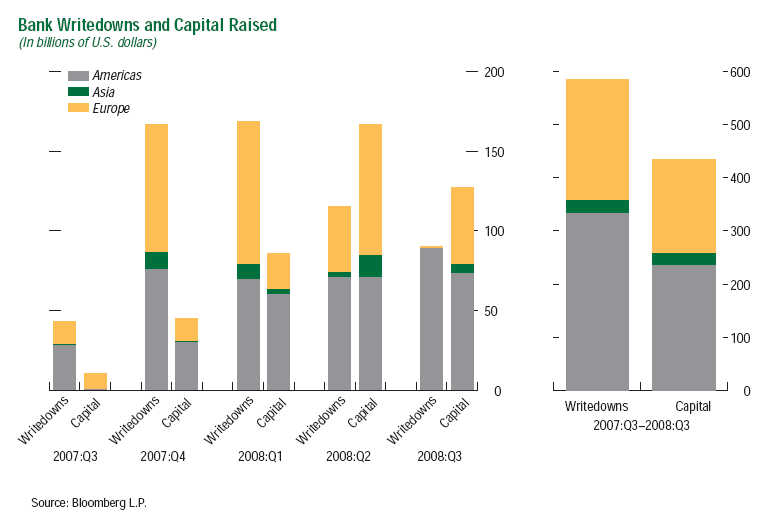

Figure 1: IMF, Global Financial Stability Report (Oct. 2008), Box 1.3.

Candidate Explanations

In particular, when one examines the mixture of policies and events that have led us to the brink of possibly the deepest and most persistent downturn since the Great Depression, one can see several suspects listed.

- Fannie and Freddie

- Community Reinvestment Act

- CDO’s and CDS’s

- Global saving glut

- Monetary policy

- Deregulation

- Criminal activity and regulatory disarmament

- Tax cuts and fiscal profligacy

- Tax policy

Red Herrings

I’ve already dealt with the first two “betes noire” — favorite villains in the fevered commentary of certain noneconomists — in this post, so we can dispense with these as key drivers (Jim attributes some blame, here, although I don’t think he attributes central blame here either). I don’t think CDO’s and CDS’s in and of themselves caused the crisis, although they certainly obscured the primary problem of overleveraging (CDO’s) and lack of transparency (CDS’s). And the saving glut — well, the saving glut was a worldwide phenomenon, but I think it safe to say the countries that did and didn’t borrow from the Chinese have suffered in the current crisis (here is my critique from 2005; CFR report [pdf]).

Synergy

So what I want to think about is the toxic mixture of the last five items, which interacted in a synergistic manner to place us in the situation we are now in.

First, monetary policy. While there seems to be a widespread consensus that it was too lax in 2002-04, this is a viewpoint made with the benefit of hindsight. As Orphanides and Wieland (2007) [pdf] have pointed out, according to the Greenbook forecasts, monetary policy was not — according to a Taylor rule framework — overly lax.

Second, deregulation. On this front, I think it’s important to not indict all deregulation (eliminating the Glass-Steagall barriers makes sense to me, while the Phil Gramm-sponsored Commodity Futures Modernization Act exemption of regulation of CDS’s does not). I outline some empirical research on what factors were important in this crisis in this post.

Third, regulatory disarmament/nonenforcement and “criminal activity”. I would have discounted this item in the absence of clear evidence, but now that we know about how the OTS “helped out” IndyMac [2] [3], I think we can be reasonably confident that we’ll hear a lot more about how deregulatory zeal [4] [5] metastatized over into criminal activities on the part of regulators and the regulated.

Fourth, fiscal profligacy via tax cuts. I think it’s important to focus on profligacy (because it pushed the economy more into a boom exactly at a time when not needed) and on tax cuts (because it made people feel like they had more discretionary income than reasonable), thereby pushing the asset boom.

Fifth, tax policy. In particular, I have been thinking about the tax deductibility on second homes, a provision dating back to 1997 [6] [7] [8]. (I’ve been thinking about this in part because mortgage deductibility on a second home never made sense to me, let alone on a first home). Capital Games and Gains has pointed out this provision, citing a NYT article. But even this last article doesn’t locate primary blame here; rather it’s cited as a contributing factor. I suspect that on its own, this provision wouldn’t had a big impact, but in combination, it might have. My caveat here is that I haven’t found much empirical work backing a big role for this factor.

Typically, in my academic work, I would think of these factors adding up in a linear fashion, so that each of the impulses would sum to the total effect. But (departing from a model, and with no econometric work to back up the hypothesis interactive effects), I think it’s worthwhile to think about lax monetary policy, deregulatory zeal and criminal activity/regulatory disarmament, and tax cuts and tax policy changes, all combining to lead to the “bubble” (in a nontechnical sense) we’ve witnessed, the deflation of which has been associated with the ongoing financial crisis.

Consider one example of a pernicious synergy: the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts were aimed at higher income households, while the second home mortgage deductibility benefited mostly higher income households [9]; with regulatory oversight absent, and low interest rates, well the stage was set.

Prescient, or Not

I won’t claim to have foreseen the full enormity of the crisis we’re now undergoing. As I indicated when I posted my first blogpost some three years ago, I thought the sheer irresponsibility of the fiscal policy being pursued, against a backdrop of overconfidence in largely nontraded derivatives, would lead to grief in the form of a “sudden stop” of net capital flows to the US. In this respect, I was wrong — what we’ve achieved instead is a sort of “global sudden stop” where the process of deleveraging proceeded in a discrete (and “disorderly”) fashion. So, unlike some, I was only partially — not completely — blindsided. (And, I’m sure Akerlof and Romer were completely aware of what was coming…)

I believe history will look critically on the Bush Administration’s economic stewardship, in particular how the policies propelled an unsustainable bubble, and tied our hands in the use of fiscal policy tools. In sum, I think Kevin (Dow 36,000) Hassett’s view “Bush’s Legacy May End Up Better Than You Think” will not prove true.

Technorati Tags: financial crisis, recession,

subprime, regulation, Bush Administration, Office of Thrift Supervision, Fannie Mae,

and Freddie Mac.

Given your inveterate disdain for Bush, this particular attack was fairly well-reasoned. However, I think profligate better applied to Bush as regards his reckless spending than his taxing (we still pay a hellova lot of tax).

History should “look critically on the Bush Administration’s economic stewardship” without a doubt. But the crux of our collapsing credit bubble is a lot bigger than Bush. It was generated by the Fed & other central banks (aka, so-called global savings glut), exacerbated by financial innovations that were miles ahead of regulators.

Many, many things contributed in small ways such as the rating agencies being converted by federal regulations into an oligopoly paid perversely by lenders rather than borrowers (as they would be in a free market). Fannie, Freddie, CRA may have been minor but still lubricant for the direction of the credit bubble.

Sure Bush is as feckless as Hoover & Roosevelt, but he didn’t cause the credit bubble that is the quintessence of our economic crisis.

it looks more like an engineered, rather than a natural boom/bust cycle bubble.

take the SEC for example. a muppet was put to run it. he has no experience or knowledge in the financial regulation field.

add to this the overall lack of desire for regulatory intervention during the boom phase and compare with the hysterical screams for more regulation during the bust phase, and anyone can easily see the problem is in the regulatory enforcement body rather than the regulatory framework.

so this looks alot like a failure by design: meant to enable more powers to the regulatory body so it can distort market forces further, while justifying its own parasitical existence.

Leverage is a pretty normal toxin.

Unique to some degree is the lowering of barriers and the super-sizing of the players involved. Network systems with few bottlenecks tend to be very hard to damage with the loss of a single node, but when they have problem, they tend to be catastrophic.

Partial discussion:

http://chaos1.la.asu.edu/~yclai/papers/PRE_02_ML_3.pdf

Algernon, consider your options should you decide to domicile in a country that collects less tax: in the OECD, only Japan (barely), Korea, Turkey and Mexico. Nowhere else — not even “low-tax” Switzerland — qualifies. Nuff sed, I hope.

And please, the CRA? Fannie and especially Freddie’s actions contributed. I was short FRE futures for a reason. But the CRA had as little to do with the crisis as the ADA. Perhaps less.

On-topic, with Bush I prefer to focus on his obvious executive malpractice. His fiscal policy, including especially those giveaway tax cuts to your Paris Hiltons, Walton heirs and Koch brothers, was abysmal — but it didn’t much contribute to the ‘global sudden stop.’ His and his party’s approach to regulation (as best I can tell: delete completely wherever politically viable, emasculate silently wherever not) probably did, but that approach is shameful even if nothing untowards occurs (see Reagan, Saint Ronald).

I hate sounding even a little like I am defending Bush, but while ‘history’ may well tie him to this crisis, it isn’t strictly his fault. The ‘sudden stop’ comes from a lot of different places in classic network-cascade fashion. I prefer to tie him to his abysmal stewardship of the executive branch, his catastrophic policies overall and his rather amazing ability to wipe out sixty years of American mythology in a half-decade stroke of war crimes and torture.

Minzie, is it time for you to start your own political blog and leave the economics to econbrowser?

I have to admit there is always the partisan in me that wants to label one proximate cause as the root of what has happened. There is no one action that Bush undertook that is to blame, but a great many actions and inactions that added up.

However, I place primary blame on Greenspan for this. Monetary policy should never have been anywhere near as lax as it was during the 2002-2004 period. The threat posed by the 2001 recession was not great enough to warrant that level of action. Granted, economic indicators in 2002 were on the verge of tipping negative again, but the threat of economic disaster was not present. It certainly did not warrant leaving interest rates at 1% throughout 2003 and a good portion of 2004. There had been no signs of a housing bubble prior to 2002, but then housing indicators began to accelerate rapidly. What’s more is that when a housing bubble began to become apparent, the Federal Reserve should have reined it in not only through higher rates but also by applying significant pressure to banks to tighten up what they were doing in creating new mortgage products that made housing credit far too loose. However, Greenspan specifically lauded the new products specifically because they did so greatly expand the availability of credit.

Bush’s role is one of being far too permissive. Despite all of the popular attacks on excessive spending or tax cuts that caused this, that really doesn’t make sense. Economic growth never got particularly overheated. Bush’s GDP growth rates exceeded 3% only in one year(2004). Only in the financial services and export sectors was growth ever that strong. His economic growth record even excluding his two recessions is quite weak. What’s more is that large deficits should have raised interest rates on long term treasuries and made credit marginally less available. What his sin in this episode has been was creating a regulatory environment that encouraged the formation of extremely large pools of trillions in unregulated capital in the investment banks and hedge funds that sloshed rapidly from asset class to asset class and caused two significant bubbles in housing and commodities. I would also maintain before all is said and done we will recognize many emerging markets were also bubbles fueled by excess investment and debt. It is all too clear now that commodities prices were fueled by speculative excess. The significant inflation caused by those price increases did have negative effects on aggregate demand in developed economies.

The SEC’s default policy was to simply let the shadow banking system do whatever it wanted. They could have enforced tighter margin requirements and try to reduce the extreme over-leverage in the system. However, they did not. Bush never warned for a moment about impending disaster. Instead, he always tried to take credit for surging home ownership rates and the fact that real estate was appreciating at great rates. He maintained his policies were responsible for whatever economic growth we experienced, however weak that may have been. As such it is entirely fair to saddle him with the blame.

I will add, with a nod to Menzie, that Bush’s deficits do make it difficult to respond properly to the crisis now. We are in a pattern of serious structural deficits for the next few decades without radical changes. Once revenue forecasts for next year are properly updated, we will likely see a deficit that would have been pushing $600 billion before additional fiscal stimulus. Individual income, corporate income, and capital gains taxes will all be plunging while unemployment compensation claims are surging. The only thing cutting in our favor is that debt interest costs will be down significantly. If the government wanted to lock in cheap money for the next decade, it could easily do so now.

With this size of a deficit, which is $230 billion larger when you take into account we are borrowing that much from Social Security to finance current expenditures, it is harder to respond than if we had been in balance going in. I suppose if you measure our public debt as a percent of GDP, our national indebtedness is not that disasterous. We could borrow another four-six trillion by that measure before we approach calamitous levels. However, if we count the Social Security debt that is owed by the General Fund, then our margin for error is much narrower.

An interesting post and though I voted for Bush twice (with no regrets), I agree with most of it. However, I would suggest that elections and politics are merely reflections of ourselves. This last election came down to a profligate airhead (who won) and an economic illeterate. It’s not like we’ve got much improvement in store for us.

Whether it’s enormous swaths of black men being thrown in prison after growing up without fathers or it’s a Federal debt of over $10T, it’s pretty evident that we didn’t want to earn what we got, whether that was sex or goods and services.

The party is almost over. Clean up is going to be a real pain. Let’s take one last, huge swig from the Keynesian champagne bottle before we reach for the aspirin and the brooms.

Brian, why do you call them “bush’s deficits”? I blame congressional republican’s (ie Tom Delay) inability to rein in democrat spending the way Newt Gingrich did in the 90’s. It was Gingrich who first balanced the budget and overrode cut capital gains taxes in ’95 (overriding a clinton veto), leading to a bull stock market, increased investment and higher productivity growth.

My point is, the legislative branch has a much greater influence on the economy. A mistake Bush made was to vow to work with congress and not use his veto power. Little did he realize that congressional republicans would do him in.

So exactly what does Obama plan to do to chart a better course? Or is the ‘we inherited this mess’ excuse going to be the only strategy?

What very few people realize is that the Gingrich congress turned into an overspending congress, despite Republican control….

Brian Quinn: A reasoned perspective; I concur on the issue of the Fed, in particular the regulatory initiatives it could have undertaken. Regarding the reason why long term rates did not rise with the deficits, see this paper interpreting the saving glut.

For a picture of projected debt/gdp ratios pre-crisis, see the graph in this post.

MikeR: Thank you for your constructive and insightful suggestion. I also thank you for your very interesting interpretation of how our structural budget deficit arose.

I think I will predict that the US economy will be sluggish for much of the next decade, even if we are technically out of a recession. The unemployment rate will not go below 5% at any point before 2017.

Most baby boomers are going past their earnings/consumption peak, and are retiring over the next decade. This spells disaster for housing, and to a lesser extent, stocks.

US real wages will not rise until China’s per-capita GDP becomes more than half of the OECD average, given how much more work will be globalized. This, too, will take until 2017. US wages will not rise until 2017.

Any disagreements here?

You make some great points here, but I think you underestimate how leverage is always going to be present. What happened here that was so unusual is not so much the leverage, but the open spigot to allow people who had no business being so leveraged to get so leveraged. We obviously will be paying for this for a long time. I urge you to check out this post on a somewhat related use of leverage involving Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Thinking more about this, your post seems a little misdirected. The choice was not between Bush and an economic giant, it was between Bush and Gore and then Bush and Kerry. It’s kind of hard to claim that either Gore or Kerry would have been much better given the Democrats’ steadfast defense of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the face of attempts to regulate them.

Also, you’d have to make the case that overspending would have been less with Kerry or Gore. Given the rhetoric coming out of the Democrats right now and during the 2000 and 2004 campaigns, that’s a really hard sell.

We’re about to see just what the Democrats can do.

(Hint: it involves spending lots of money.)

Fundamental assumptions seldom get discussed. That is especially true of the assumption that the financial system controls the level of the current account. The competing hypothesis, which makes more sense to me, is that the size of the trade deficit controls the current account – and that the size of the trade deficit (trade balance) is an exogenous variable in the equation that estimates GDP (GDP= Consumption + Investment + Trade Balance.

This reverses the assumptions used both by Bernanke in his 2005 paper and Chinn in his 2008 paper.

Neither author gives a defense of his decision. Bernanke does highlight the difference between the two assumptions. Bernnake says which perspective one takes depends upon the problem at hand. This assumes the two hypotheses are equally valid – a logical impossibility. Bernanke does note that the finance controls hypothesis is widely used by economists.

The original equation is equal to GDP-C = I +TD.

Both sides of this equation equal National Savings. National Savings is an endogenous variable in this equation. This is the main reason I prefer to assume that causation flows from the trade deficit to the current account and that all the financial implications of the current account are ultimately controlled by the size of the trade deficit, which is a causal variable in the original equation.

I realize a point as important as this should be discussed by an audience that read refereed papers. I apologize to those who do not want to consider fundamental assumptions.

I agree with those who argue that the seeds of the current disaster were sown in the i1980’s long before Bush came to power. All during that decade, the Republican Party was urging greater deregulation AND THE DEMOCRATS HAD NO EFFECTIVE RESPONSE – largely because Reagan had convinced most voters that the government was the source of any unease or dissatisfaction they faced. The Democratic party consoled itself with trying to increase home ownership among those who had been left out – due to race or poverty.

Both parties contributed to the climate of opinion that was unable to see clearly what was happening to us.

Bush not only believed in deregulation by legal means he believed in deregulation by illegal means – neutering enforcement agencies.

Yes, we all will pay for decades of stupidity and overreaching and overconfidence.

It seems to me that a pretty good case can be made that this entire mess is due to one man’s vanity. Greenspan held interest rates down in the early part of the decade because he didn’t want to retire as the man who caused the dotcom bubble and collapse. So he retired on a high note but now is universally regarded as the man who caused two bubbles. This in itself is a pretty good argument for eliminating the Fed and having the politically accountable Treasury absorb its functions. But this raises another possible motivation for Greenspan’s minimalist monetary policy in the first Bush administration. A more stringent monetary policy might have indeed caused a second recession in 2004 and doomed Bush’s re-election. It is not likely that this would have very troubling to the FED. However, it might very well have prompted more critical demeanor from Republicans toward the FED. So the low interest rate policy was insurance against political accountability. Now the FED will be compelled to keep interest rates low, probably for decades. Any effort to raise rates will prompt political criticism which is the one thing the FED cannot tolerate. The conclusion is that FED has ceased to exist as a true central bank in the modern sense. And in some sense one has to wonder if that wasn’t Greenspan’s game all along. The old libertarian and gold bug has proved that central bank monetarism is a myth.

Ray, what portion of the blame for our financial mess goes to “deregulation”? Regulation is not nearly as important to well functioning capital markets as is rational expectations and self interest. The profit motive of individuals is more powerful than regulation. Menzie talks about the problem of asymetric information, so I support regulation encouraging full disclosure and transpearncy.

Regulators are always fighting the last war. Tight regulations on the banking industry lead to the creation of the “shadow banking” system, starting with money market accounts which eventually lead to the Savings and Loan scandal. Sarbanes Oxley did not prevent Freddie from issuing false accounting statements in 2005, nor did it prevent the options backdating scandal. Regulation of the ratings agencies gave them a defacto government mandate. One should never trust another person’s opinion when it is your money on the line. But the government accredation of “statistical rating agency” gave them abnormal market power. Eliot Spitzer forced out Hank Greenberg, Greenberg’s replacement encouraged the growth of the financial products division at AIG which required a government bailout. Spitzer completely missed the Madoff scandal.

When it comes to regulators, the buck stops with congress. To bad Barney Frank is not up to the task:

House Financial Services Committee hearing, Sept. 25, 2003:

Rep. Frank: I do think I do not want the same kind of focus on safety and soundness that we have in OCC [Office of the Comptroller of the Currency] and OTS [Office of Thrift Supervision]. I want to roll the dice a little bit more in this situation towards subsidized housing.

I agree with Barney Frank… roll the dice, but buyer beware!

History is hard on conservatives. Time after time reality impinges on ideology and proves them wrong

One of the best examples of this is Bill Clinton’s first budget. It is the budget that raised taxes and it passed without a single Republican vote, not a one. The conservatives said that voting for a tax increase, and passing one, would lead to slower economic growth. The real world however does not behave like conservatives believe it does. In actual fact the higher taxes led to lower government borrowing with led to lower interest rates which led to lower costs for corporate borrowing which led to higher capital expenditures which led to higher growth which led to higher tax revenue which led to lower government borrowing …. a virtuous cycle was established, as predicted, and the economy boomed.

Clinton proved that tax increases actually acually have a beneficial effect when reduced government borrowing is the result.

The current economic mess is another example of failed conservative ideology. In the real world government oversight and regulation, done properly, is required for a smoothly functioning economy with profits and benefits honestly earned.

Is it possible that costs of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars might have something to do with the massive U.S. debts and resulting financial chaos?

MIKE SAYS: “The profit motive of individuals is more powerful than regulation”.

Regulation including laws, are intended to define the channels within which the profit motive can operate to serve the interests of the wider society – theoretically. Such laws were passed under the Roosevelt administration. And they did succeed in directing the profits making opportunities – and closing off some profit making opportunities. The classic example of refusing to close off profit making opportunities is the Commodities Future Modernizations Act of 2000. The act prohibited regulation as well as public information from being required for certain specified financial activities. Said activities are the “instruments” that have put numerous firms out of business. That act was essential for the extremes of what happened to exist. The act also required the U.S. courts to enforce all these private contracts that were not to to be made public.

The profit motive is fine. However, the people who are interested in doing things that enrich themselves at the expense of the rest of us should not be allowed to write the laws that deal with their activities.

ken, the fly in the ointment is the assumption of regulation ‘done properly’ as you say. That is the problem socialists have been dealing with since time began. They believe they can gain or already have the knowledge required to regulate properly when, imo, that is the fatal error that has doomed every planned economy in history. Give me unequal liberty over equal misery anytime. What most people call conservative or liberal ideology is nothing of the sort but, simply competing political parties. The real issue is freedom or lack of it. The conservative tends to favor freedom while the liberal believes people must be constrained from doing ‘bad’ things.

Personally, I find socialists in every form reprehensible for many reasons. Every motivation that drives them from conceit in one’s ability to regulate to the desire to prevent others from gaining too much comes from evils. The seven deadly sins if you will. Pride. Greed. Yes, I know liberals believe conservatives are the greedy ones but, reality is different. Envy is what compels the desire to take from those that earned too much and spread it around. Robin Hood is considered a hero instead of the common thief he was. All science, whether economic or atmospheric is twisted and abused by politicians and others for their own ends. Both political parties pander to the lowest common denominator, the basest of emotions, or the seven sins if you will.

True conservative believe as our founding fathers that all government is tyrannical. All politicians will succumb to corruptness in time and government should be bound by chains to prevent its usurpation of the liberty of the people. It takes an incredible hubris to believe that increasing taxes is good. Morphine is good also but, see what happens when you have too much goodness.

Just more unpatriotic negativity from liberals who question America, and the troops.

Much thanks to all the winger commenters for proving that the conservatives are incorrigible…

Several issues –

As to what is exogenous or endogenous, China engaged in substantial purchases of dollars, and currencies are not perfect substitutes for each other, so it is not clear that this practice did not ‘force’ more current account deficit onto the U.S. than would have resulted if Chinese saving had been market determined.

Your work in 2005 on the twin deficits is not a ringing endorsement for fiscal stimulus and should be read by anyone inclined to ignore the effect of the stimulus on the external deficit – i.e. the amount of ‘leakage’ is not exogenous.

As to where to assign blame for the present situation, I am reminded of the question of whether misbehaving kids or ‘enabling’ parent are primarily at fault. The saving ‘glut’ is in no small part due to currency policies that distort relative prices, including not only China’s explicit intervention, but the yen carry trade which was encouraged greatly by the widely (and I believe correctly) held view that the Japanese authorities would step in to prevent too much yen appreciation.

The leveraging issue can misdirect saving, but it does not increase the total amount loaned.

allis wrote: Is it possible that costs of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars might have something to do with the massive U.S. debts and resulting financial chaos?

——–

Add agricultural subsidies and the ethanol program.

US support over the past several decades for the violent acquisition of religious monuments and arid farm land in the Mid-East lead to the economic and technological blockades of 3 important sources of light sweet crude oil (Libya, Iraq and Iran), another contributing factor to record high oil prices in 2008.

Putting all the blame on the Bush II administration for the Middle East morass and the current economic mess is not just misleading but inaccurate, and not conducive to finding constructive solutions going forward. American liberal economists are also to blame for the blow back and failures resulting from aggressive colonial policies in the Mid-East.

There is one bubble/bust that bears some resemblance to the current one, that which occurred in the early 1980s. In both that and the present situation, the Fed had intentionally held policy rates negative in real terms for an extended period of time. In both cases, both inflation and reckless real estate lending followed.

When rates became positive later on, the money started flowing out of speculative real estate and it crashed.

Suppose that there had been excess money and also tight regulation of United States lenders. Wouldn’t that money have gone into other countries’ banks and other investment classes, creating a bubble and crash anyway? Well, a good portion of it did, if one is to believe recent reports of European banks making huge dollar-based loans in emerging commodity-based economies. Reckless lending collateralized with inflating tangible assets seems like a sign of a loose money bubble, whether the collateral is real estate or copper ore. The outcome, loans gone bust and bank insolvencies, is the same no matter who the bad borrower is or what speculative asset collateralized the loan.

The most recent annual report of the Bank of International Settlements argues for the loose money hypothesis. It pointed out that bubbles existed across a wide range of assets including stamps and fine wines.

There was no change in the regulations associated with markets for stamps or wine. Furthermore, home prices rose rapidly across a wide swath of countries with differing lending standards. In fact they rose 78% in Canada from 2002 to 2007 without a corresponding rise in incomes, faster than our home prices (http://www.financialpost.com/money/family-finance/story.html?id=981668).

If a broad set of asset classes rise rapidly during the a time period, in spite of completely different regulatory regimes, it seems problematic to isolate regulatory changes or even a toxic brew of regulatory and monetary issues as the cause of the rise in one asset class. This goes whether you are pointing the finger at Bush or at Barney Frank.

Here is the quote: http://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2008e1.pdf

It is perhaps best to begin by noting that policy interest rates in the advanced industrial countries have latterly been unusually low by postwar standards, due to the absence of any strong inflationary pressures. This outcome reflected the building-up of central bank credibility over many years, but was also facilitated by a combination of positive supply side shocks, largely related to globalisation, and weak investment demand in a number of countries (including Germany and Japan) in the aftermath of earlier periods of excessively rapid expansion.

This policy stance might have been expected to cause a general depreciation of the currencies of the advanced industrial countries, particularly the US dollar, relative to emerging market currencies. However, in many emerging economies, upward pressure on the currency was met over an extended period by an equivalent easing of monetary policy and massive foreign exchange intervention. The former is likely to have contributed to higher asset prices and increased spending in the emerging markets. The latter, via the investment of official foreign exchange reserves, is likely to have further eased financial conditions in the advanced industrial countries. In this way, the monetary stimulus to credit growth became increasingly global.

This is not to deny that changes in the financial system over the years have also contributed in an important way to unfolding events. In particular, the various innovations associated with the extension of the originate-to-distribute model have had a major impact. Recent innovations such as structured finance products were originally thought likely to produce a welcome spreading of risk-bearing. Instead, the way in which they were introduced materially reduced the quality of credit assessments in many markets and also led to a marked increase in opacity. The result was the eventual generation of enormous uncertainty about both the size of losses and their distribution. In effect, through innovative repackaging and redistribution, risks were transformed into higher-cost but, for a while at least, lower-probability events. In practice, this meant that the risks inherent in new loans seemed effectively to disappear, buoying ratings as well, until they suddenly reappeared in response to the trigger of some realised loss that was wholly unexpected.

It is also a fact that, prior to the recent turbulence, the prices of many financial assets were unusually high for an extended period. The rate of interest on long-term US Treasuries (the inverse of the price) was so low for so long as to be dubbed a conundrum by the previous Chairman of the Federal Reserve. Moreover, the risk spreads on other sovereign debt, high-yield corporate bonds and other risky assets also fell to record low levels. Equity prices in the advanced industrial countries continued to be well (if not clearly over-) valued, and those in many emerging markets rose spectacularly.

Residential property prices hit record highs in virtually all countries with the exception of Germany, Japan and Switzerland, where property markets were still recovering from the excesses of the 1980s and early 1990s. Even the prices of fine wines, antiques and postage stamps soared. Similarly, the cost of insurance against market price movements (approximated by implied volatility) was sustained at unusually low levels for many years. Admittedly, arguments about fundamentals can be adduced to support independently each of the above trends. However, in the spirit of Occams razor, it is particularly notable that all of these patterns are also consistent with credit being freely available and having a low price.

Finally, it is also a fact that spending patterns in a number of countries have deviated markedly from what had been longer-term trends. In the United States and a number of other major economies, household saving rates trended downwards to record low levels and were often associated with mounting current account deficits. By contrast, in China there has, equally unusually, been a massive increase in fixed investment. As with high asset prices, these patterns are consistent with a plentiful supply of cheap credit.

Taken together, the above facts suggest that the difficulties in the subprime market were a trigger for, rather than a cause of, all the disruptive events that have followed. Moreover, these facts also suggest that the magnitude of the problems yet to be faced could be much greater than many now perceive. Finally, the dominant role played by rapid monetary and credit expansion in this explanation of events is also consistent with the recent rise of global inflation and, potentially, higher inflation expectations.

“Putting all the blame on the Bush II administration for the Middle East morass and the current economic mess is not just misleading but inaccurate, and not conducive to finding constructive solutions going forward. American liberal economists are also to blame for the blow back and failures resulting from aggressive colonial policies in the Mid-East”

Incorrect. The Bush admin caused alot of the problems because they wouldn’t follow the rules and instigated a meaningless war for the war profiters because they thought it could stimulate some growth.

The bubble was set when all the hot money from the post-Asian crisis era flew into the US. The Bush admin’s reaction was pathetic. Not upping interest rates above which the market wished and then taking all the capital rules off set the stage. Forget about the tax cuts, they are pretty meaningless to this discussion. The former, however gets to the heart of it.

The fact is, that cash was used for a big speculative bubble that as all bubbles do, blow up, whether it be 1836, 1873, 1892, 1929, 1973…..get the picture?

The middle east was not a problemtic area like you seem to suggest. It was a war profiter created trouble because the Bush Admin would not leave them alone. The Neo-cons were so desperate for growth, they tried about anything to get it.

I think being jealous that the tech boom happened under Clinton’s watch made it worse. Instead of being a little unhinged, they went outright nuts.

KTcat: “Democrats’ steadfast defense of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the face of attempts to regulate them “.

How many times does this need to be refuted ? Our current economic morass is a bi-partisan mess. Other than SB 190 there were no attempts to regulate F/F. and SB190 dealt with accounting scandals. It’s solution was to securitize then sell their remaining portfolios, throwing even more MBS into the mix.I believe this is why it failed, would have made things even worse. and there was a Republican majority at the time. It really is time for folks to get off their respective party soapboxes and think for themselves.

Actually, the fault is Keynesian policy. We learn that when we have economic contraction, we use monetary policy stimulus to create another credit creation and we also use fiscal policy to create spending. Those cause over consumption and production not only in US but globally.

Now US and global have too much debt in private and public. We have real estate and stock bubbles that have already been crashed.

We are wrong to think that short term optimal policy is best for long term now Keynesian policy prove us it is wrong. We have to think the right policy for long term. Keynesian taught us with short term policy but he never taught us what will happen in the long run when all tools are struggled with huge debt.

Growth model taught us the old and new generation and how to be the optimal path. But we look only our generation to be prospered and create debt for next generation and we can see the huge debt meaning huge taxing for the next generation. Is that good policy to use new generation money for our prosperity?

Can anything constructive come out of this conversation? I would like to establish one point on which all should be able to agree.

Keynes 1936 book described how to get out of a depression. But it did say that the stimulus should be reversed after the depression was passed and that taxes should exceed revenue during normal times to pay off the debt incurred to overcome the depression.

Anyone disagree with this? The U.S. policy of CONTINUEING with a fiscal deficit during “normal” times is not Keynes’ policy.

Don’t blame Keynes for U.S. actions.

MIKE SAYS : “Tight regulations on the banking industry lead to the creation of the “shadow banking” system, starting with money market accounts which eventually lead to the Savings and Loan scandal”.

Bankers were making plenty of money in the regulated banking system. The urge to escape regulation is always present. The failure was the lack of regulatory zeal which allowed the “shadow banking” system to come into existence. No law of nature says the the finance sector should continually increase its share of GDP during the 25 years after 1980.

The lack of regulatory zeal is due to the influence of Ronald Reagan, who showed how to change the climate of opinion in the U.S. to oppose regulation of the “shadow” banking system.l

I am responsible for the above post under Anonymous at 5:19PM.

Great wonk discussions here. But what will America produce or innovate (other than perverted financial instruments) for export to other countries in the future? Or will the rest of the world continue to gladly throw money at us for ever and ever because Treasuries are so wonderfully safe? All i keep hearing is “Reagan proved deficits dont matter”, blah, blah, blah. Or “Everyone will always but T-bills so we can borrow money to but their stuff” I get the feeling this infantile consummtion has its limits.

We should not blame Keynes but we should blame the way we use Keynesian tool. We focus short run never look at long run or the next generation. We use monetary and fiscal stimulus to support economy in the short run to move back to normal path but we never take about how to bring down debt created by loosening monetary policy and public debt created by fiscal policy and now we, US and world, are in debt bubble. Japan have 200 % of public debt and US next year will have 80-90% public debt. How can we reduce those det? Noone say about it. Everyone say about how to sustain economy back to grow but everyone knows that we cannot sustain economy with overconsumption, overproduction and overdebt.

The U.S exported 1.1 trillion dollars worth of goods last year. Our problem is infantile consumerism, to quote AlexR.

When the voting public becomes’ convinced that the U.S. should stop consuming more than we produce, a way will be found to restrict the level of imports to the level of exports.

Oso, you’re absolutely right that the Republicans had the majority, although I’m not sure if the Democrats in the Senate would have filibustered attempts at reigning in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. My point was not to assign blame, but instead to suggest that it’s not clear things would have been any better under a Kerry or Gore administration.

The ignorant ‘Samual Jackson’ wrote :

“The middle east was not a problemtic area like you seem to suggest. ”

I can’t believe that there are actually people who think the ME was a wonderful, peaceful place before 2001. How wilfully dumb does a person have to be?

Hitchhiker says: “True conservative believe as our founding fathers that all government is tyrannical”. True conservatives believe a lot of things that I would call extreme.

It is true that the founding fathers revolted against the tyrannical government of Britain. It is also true that they gathered in Philadelphia because the separate states were weak. If the founding fathers were interested ONLY in restraining the power of government they would never have written the U.S. constitution.

The founding fathers had a vision of the kind of nation the U.S. could become if the various states were united into one nation. The government they established had sufficient national power to control the nation but also means to distribute power to avoid tyranny. This balancing act has been modified with time.

Regionalism or nullification was the issue faced by both Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln. In both cases, regionalism lost.

Extending the power of “the people” over the power of the elites was the second issue, faced by Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Roosevelt and now by Barack Obama. In all cases thus far, the elites lost. I am confident the elites will lose in the current contest.

The conservative movement has had its day. The willingness of the elites to allow the U.S. financial system to self-destruct because profit making was not reigned in, forced to serve the general public, is the lesson of the past two years.

Obama will not assume that all governments must be tyrannical. He is willing to use the power residing in the federal government. My question is whether he is intelligent enough to break out of the stereotypes of the day and curb imports so that the manufacturing sector can recover.

Unbalanced trade has played a large role in the excesses observed in the global economy in the last decade.

The dollars possessed by developing countries, part of what Bernanake calls “savings glut”, was created because these developing nations created a trade surplus after the Asian credit crisis of 1998. These dollars, plus Greenspans low interest rates, created excess liquidity. This excess liquidity did not lead to inflation because Chinese imports into the U.S. were becoming cheaper all the time, preventing U.S. firms from raising prices.

The threat of outsourcing destroyed the pricing power of labor unions. The cash in the pocket of voters in the U.S. (and peasants in China) created public support for the ruling elites.

The trade deficit in the U.S. is at the center of events.

Explanations that focus on financial issues confuse consequence with cause.

Is there a way to display this blog without Menzie’s posts? His quaint political rants are ruining was what a great economics blog.

MichaelB: Thank you for your constructive and insightful (albeit syntactically confused) comment. The short answer to your question, to the best of my knowledge, is “no”. JDH may have a more comprehensive answer.

Menzie, I am not the only person in your audience becoming alienated by political opinions but also still enjoy your data analysis. I re-read your post and found your use of the word “stewardship” interesting. It just reinforces to me the keynesian belief that there is a role for central planning.

Ken, should we really credit Clinton’s tax increase in ’93 with the budget surplus in the late 90s? You are using a one factor model. Lets propose some other factors. Correct me if I am wrong, but Reagen cut the top marginal tax rate down from 70% when he took office. In 97, congress cut cap gains taxes. So overall, taxes were cut, not increased over the time span from the ’70s to 2000. After the fall of the soviet union military spending could safely be reduced without fear of nuclear war. High inflation following vietnam era deficits, Johnson’s failed great soceity, Nixon’s price controls and opec lead to stock price declines in the 70’s. Inflation and inflation volatility steadily declined under volker and greenspan. Worker productivity soared thanks to globalization and information technology. The equity risk premium fell and capital gains went up. All this because of Clinton’s ’93 tax increase?

The UK telegraph has an article about how George W. Bush has been a superb statesman, doing he greatest job of liberation since Churchill and FDR.

MichaelB, MikeR,

If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.

There are plenty of blogs to participate in and you are free to use them at no cost.

“Is it possible that costs of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars might have something to do with the massive U.S. debts and resulting financial chaos?”

Sure, the same way driving with my windows rolled down in the summer has something to do with my paying more to keep my car fueled up.

“Much thanks to all the winger commenters for proving that the conservatives are incorrigible…”

And much thanks to all the leftie commenters for proving that lefties are every bit as blindered, deluded and willing to forego true intellectual thought in favor of partisanship as the “wingers” on which they love to blame quite literally every problem under the sun.

“Great wonk discussions here. But what will America produce or innovate (other than perverted financial instruments) for export to other countries in the future? Or will the rest of the world continue to gladly throw money at us for ever and ever because Treasuries are so wonderfully safe? All i keep hearing is “Reagan proved deficits dont matter”, blah, blah, blah. Or “Everyone will always but T-bills so we can borrow money to but their stuff” I get the feeling this infantile consummtion has its limits.”

Then you’re only listening to a very thin slice of the discussion that’s been going on since the late 90s. The idea that the U.S. does not produce or innovate is laughably ignorant and has been so thoroughly debunked in so many locations that it’s not worth getting into. And any time the issue of t-bill purchases has been brought up for the better part of 8 years it’s precisely the OPPOSITE of what you describe – people have been predicting the collapse of buyership year after year after year, and the argument is always that if it hasn’t come yet it’s going to. Sounds to me like you’ve set up and ingrained a set of straw men for yourself.

And, Menzie, your frequent sardonic “thank you” responses to posters would carry a little more of their intended weight if you weren’t increasingly egging this sort of thing on with your posts in the first place. You’re getting responses in kind.

MikeR: Well, looks like two and counting. Plenty of readers have problems with my views, but they are able to verbalize why they find the analysis wrong. If I took out every reference to “Bush” in the post, would that make the post more palatable to you?

In any case, your statement that central planning = Keynesianism suggests to me that you have bigger problems than with my political views. I wish you the best in your endeavors in finding a non-alienating source of information.

If you count MM, there are three of us. Some of the others seem to post less frequently, such as DickF.

Menzie, some of your posts contain analysis, this one has little, if any, analysis, so there is no need for me to verbalize a rebuttal.

Your post has little to do with your title – “Stuff (sh%t) Happens”: the Bush Administration’s Economic Stewardship. All you do in your post is lump together a series of events that the executive branch has little control over and suggest that his “stewardship” caused the financial meltdown. You suggest that the bush tax cuts were aimed at the rich (interesting since low income earners got the highest percentage reduction in marginal tax rates), made people feel richer leading to an asset price bubble. As already pointed out, the housing bubble occurred in other countries, even ones where Bush was not president. Having graduated from Wisconsin, I know that this is the sort of normative economics they teach there.

Bush also gets the blame for criminal activity from regulators for which you provide no evidence. Meanwhile, Congress is off the hook on Fan and Fred since you see Fan and Fred as blameless simply because they reduced the size of their subprime portfolio in 2006, but still underwrote half of the entire mortgage market and were big political donors to democrats such as Obama. Hmm, shouldn’t it be criminal to give political donations to your ultimate regulator?

Colonelmoore, excellent & insightful post. Thanks.

MikeR: Ah, much better. I much prefer actual discourse rather than mere condemnation. Regarding unsubstantiated allegations, I wonder who made this comment: “I don’t have much confidence in the ability of the government to wisely invest the money. Perhaps Charely Rangel’s son works for a good investment firm or we can get Rod Blagojevich cut some deals.”

I do question, however, the charge that there is no substance. There are a multitude of links to other posts and newsarticles in the post; in those referenced posts, there are hyperlinks to many sources.

By the way, DickF is exemplary in laying out explicitly the reasons for his disagreement, something utterly lacking in your first comment, and hence differentiates his comments from yours, MM, and MichaelB.

MikeR: Expanding on my previous comment, (i) is it really true that the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts had little to do with the Executive branch? That would be surprising to me, as I had some recollection that President Bush proposed them. (ii) Yes, housing prices rose in other countries, but the decline seemed exacerbated in the US by several factors specific to the US (in a post linked to in the post); (iii) I did not leave F&F blameless (which you would see if you had followed this link to this post), but unlike some, I have not laid the financial crisis almost entirely at the feet of those entities.

I am curious what (and how many) economics classes you took in the economics department, public affairs, agricultural and applied economics departments (i.e., outside of the business school). Otherwise, I believe you should re-think your wholesale categorization of economics at UW-Madison. I’d also be curious what departments you think are “pure” in their instruction of positive — as opposed to normative — economics.

By the way, I prefer the original Rumsfeldian quote “Stuff Happens”, as it retains the blitheful nature of the statement, and conveys more fully the worldview I was critiquing.

Although monetary inflation has been going on for a long time, it accelerated under Bush, as did deficit spending. A suitable tax structure is a good thing..if politicians are forced to pay as they go, they will cut spending instead of borrowing more as Bush did. The Iraq “war” was unnecessary and contributed at least 1 trillion dollars worth of malinvestment to the mess. Add in lax regulation stemming from the Bush ideology and the Fed committed to creating money and lending it out below the rate of inflation and presto… various bubbles based on cheap credit.

End of the year and end of an era (one hopes, even die-hard GOPs) and time to thank Menzie and James for educating us…yes, even Mike and others…who might have a narrower view of “education”, of “economics”, of “learning” and “listening”.

Oh well.

Our hosts are not doin this because their pension funds are drying up and they need the consultin fees (not following BR’s “Premium” @ Big Picture) …nor because they feel obliged to further the Communist Manifesto (the inevitability of History needing that extra little push…it could happen. It Will.), or some lesser version –perceived by those responding to the least bit of criticism of GWB…that innocent bystander who merely inherited all the difficulties from Clinton and none of the benefits.

I am indebted to both these gentlemen and scholars for giving us their time and talents, that make us better students of the economy.

Such a bargain.

But not compared to that service of engaging us, making us think, reconsider and question the mainstream views/values that were adopted with much less care …and much more marketing.

We non-economists Salute!

We citizens Salute!

Menzie, Menzie, Menzie!

Don’t you know that Bush had nothing to do with events that occurred when he was in office? He was simply the hapless victim of Bill Clinton, the minority party in Congress, and the one-third of judges appointed by Democrats?

Bush was done in by wily poor people, coached by ACORN, whose canny lies on mortgage applications eluded the diligent examiners at Countrywide, as overseen by the conscientious regulators at the SEC. And by Barney Frank, whose gay ray prevented the majority Republicans from working more than three days a week.

Any footage of George Bush pushing home ownership by poor people or photos of John McCain giving the keynote address to ACORN must be Democrat forgeries because we know Bush and McCain are Republicans, so they wouldn’t do things like that.

In short, George Bush was just unlucky, faced with foes of overwhelming power and craft. And that’s why people should elect Democrats, because they’re just not so g-d–n unlucky as to get us into the worst crisis since the Great Depression.

Which the Democrats were also responsible for.

Somehow.

Orwellian. Amazing that guys with guns forcing people to pay for what they think is better (or simply what they want) is called “stewardship”. Obama isn’t any better.

I would like to second algernon and bring more attention (and kudos) to colonelmoore’s post.

Menzie – any chance you could expand your analysis of the ‘twin deficits’ to include an estimate for how much of the proposed stimulus will leak out through the external sector (expansion of the trade deficit)?

Amazing (12/29/08 11:39AM): people calling the democratic workings of a free people “guys with guns forcing people to pay.” Because of course anarchy works so much better.

don: I don’t have an estimate, but you can see the relevant calculations outlined in this post.

calmo: Thanks for the comment — glad to see the work is appreciated.

8 years later and I still don’t understand this pathological hatred for Bush. (“war profiteers” – someone open a window and let some fresh air into the cellar).

FRE/FNM had a significant role that can’t be denied. They bought and insured the mortgage market. They were pushed to lend more and to more risky customers and they did so. They were a giant part of the market and the main reference point for all brokers.

Do they deserve 100% of the blame? 10%? I don’t think anyone knows that, but you can’t deny that they were significant players in this market.

Blaming deregulation? The financial industry is the most highly regulated industry in the world. there’s some kind of left-wing dream out there that there is some all-powerful regulator who could have prevented this.

The irony is, at least 80% of Obama’s actions will identical to Bush’s. Only in judicial appointments will there be a major difference. On economic and national security matters, the difference will be minimal or none.

People want to see certain things happen because they believe that those can make the world a better place. They believe that politicians can either facilitate or hinder progress toward those goals. As such, they tend to defend those politicians that support their goals and attack those that try to hinder them.

This is what I consider two-pointed reasoning. It doesn’t take into account a third point, which is the degree to which the world will actually be a better place if the goal is achieved.

Bush is seen as having hindered regulation of financial institutions and Obama is seen as pushing for more regulation. The assumption is that hindering regulation led to the current financial crisis and more regulation will help ameliorate future crises.

When people present me the notion that regulation or lack thereof is the primary reason we are in this crisis, I try to find data showing major differences in the behavior of markets between countries with high levels of regulation and those with low levels of regulation. So far all I have seen is that there was a generalized asset bubble, especially when priced in dollars, that followed a period of negative real policy rates. I see that this looks a lot like what happened after the last such episode, during the Nixon Administration.

If loose money itself were not the primary cause of our problems, then why were both good borrowers and bad borrowers able to freely obtain credit at low rates? If money had been properly rationed by the Fed, banks would have to willfully prefer lending to bad borrowers over good borrowers no matter how hands off their regulators were.

It isn’t clear to me how regulation could stopped bad loans from being made in the face of overly loose money. Traditionally the Fed made extra reserves available with the expectation that the banks would use them to make loans. So if we are now seeing defaults on loans that were imprudent, and if prudent borrowers were not denied credit, then the Fed’s creation of reserves must also have been imprudent.

This is why I wonder if the Fed’s loose money policies aren’t the core issue. It is what makes me think that regulation might have modified the shape but not the magnitude of the bad lending binge.

In our earnest desire to achieve our political goals, we risk missing both cause and cure. This time everyone thought that the financial models were sufficient to suspend risk; the next crisis could be precipitated by overconfidence in regulation. In the absence of proper accounting of past policies. the Fed could once again fool around with negative policy rates during a recovery. Partisans of all stripes should be able to agree that this would be harmful.

The next crisis will be unanticipated just like this one. No analysis of this one can protect us.

Colonelmoore is also a partisan looking at only part if the picture. The Commodities Future Modernization Act of 2000 is evidence that lack of regulation played a role in creating bad practices. This act said that the kind of instruments that became the “shadow banking system” would be off limits to Federal regulators, the contracts between private parties would not be registered or known by federal regulators BUT the provisions would be enforced in U.S. courts. This act was sponsored by the members of Congress who believed the no-regulation religion.

The crisis was due to several factors, among them explicit non-regulation plus loose money and wealth created in the stock market and currency speculation. Loose money alone would not have produced the results.

Menzie, if I’m reading the Orphanides/Wieland paper correctly, are you not letting the FOMC off the hook way too easily?

“The last episode is 2002-03, when the forecast-based rule correctly tracked the further

policy easing at the early stages of the recovery from the recession, while the outcome-based

rule suggested that policy should have been considerably tighter…

…we find that the rule with FOMC projections tracks the federal funds rate target quite well through the first half of 2004, and that the only noticeable deviation is that it would have already called for much more aggressive tightening starting in the second half of 2004 than actually took place.”

Assuming monetary policy acts with a lag, that economic agents make forward looking decisions based on backward looking recent experience, that ‘bubbles’ are a natural and innately human feature of financial markets, etc — can we really dismiss the impact of negative real ST rates? Note that (1) until this decade we hadn’t seen them from the FOMC since the 1970s and (2) despite the deflationary feel of the past several months, long term trends show that we are in a period of receding inflation rather than outright deflation.

Without the benefit of formal empirical analysis, I think the most solid explanation for the crisis would amalgamate ReformerRay and colonelmoore’s last posts with the SEC’s 2005 rules on capital and leverage (plus similarly loose capital rules overseas). Interest rate spreads show clearly that this is a private sector credit crisis. Public fiscal profligacy will certainly tie policymakers’ hands in the future, and could very well play a role in future crises, but I don’t see how it could have contributed significantly to this one.

Negative real rates were amplified by insanely high leverage. Professionally, I was a witness to the process. What was happening in non-OCC and similar channels — investment banks, broker-dealers, hedge funds, private equity, etc — was extraordinary. And the idea that a ‘perfect hedge book’ could be levered infinitely became the prevailing “rule-of-thumb” in finance. The CDS market became probably the least regulated financial market relative to its size and potential impact EVER, and was the reason AIG became a potential ‘node failure’ that scared the bejeezus out of so many people.

Finally, I would add that the US corporate tax code has been a source of widening competitive disadvantage for decades now, and that’s been compounded by the well intended but poorly designed and extremely costly elements of Sarbox (excessive monetary easing when real economic prospects are more attractive overseas was a key feature of the late 1960s-1970s). Rising pessimism over tax and regulatory direction since the Congressional elections of 2006 may have played a role as well. Lest I be accused of partisanship, I also agree with Menzie’s argument that the long term process of GDP-per-capita-narrowing (e.g., between US and China) is an inevitable feature of global integration, and is responsible for some of its less pleasant effects in developed countries. Question is, what are the tradeoffs of reversing such a process, as folks like Dani Rodrik think could happen? I shudder to think.

JoshK: Absolutely, parts of the financial industry are among the most heavily regulated in the world. There’s a reason for that, as any money&banking textbook explains. The question is whether that regulation was sufficient, appropriate, and comprehensive enough. After all, there is a reason for the term “shadow financial system”.

ap: Well, it’s a matter of degree. I did put monetary policy in my list of interactive factors. I suspect in the absence of the other factors (deregulation, overleveraging), we’d be doing some adjusting, but not as much as we’re seeing now. The point I was making was that given the forecasts, the policy was not as implausible as it now seems with the information we have on actual GDP, etc.

Menzie, fair enough on the synergies; and the Fed’s forecasts would have predated known outcomes. A couple of quibbles~

(1) As I wrote in my second post (as anonymous, accidentally), all of that leverage was amplifying what was effectively a negative cost of money. That shouldn’t have been allowed to happen of course. But applying the tactic you just used, how bad would it have been in the in the absence of negative real rates? We might arrive at a similar answer to yours. No one is innocent, as they say.

(2) The term “deregulation” is being thrown around too loosely. For the most part, important players in the crisis never were regulated; mortgages were, technically, but OTC derivatives were not, even though the alarms were being sounded by enough people to take notice, and they represented (notionally anyways) the most significant component of systemic leverage (that and USDs abroad – remember the eurodollar ‘crises’ of the 1960s and 70s?). I think “ineffective” or “insufficiently adaptive” regulation might be more descriptive. That said, shouldn’t we aim for something broad (i.e., comprehensive), that is also reasonably shallow, effective, and responsive/adaptive? Like an optimal tax system?

On that last one, I think those SEC capital rules in 2005 were a huge culprit, and I’ve been struggling to get my head around them. Where’d they come from, and why’d they come about? This just occurred to me, and it’s pure speculation, but could they have been related to the push for hedge fund advisor registration, e.g., in exchage for closer scrutiny of managing partners, we’ll let your primer brokers go crazy? Anyone have any insights?

ReformerRay, I am happy to learn from the insights of others on any matter as long as I can be convinced that X is a major cause of Y rather than a minor cause or just correlated.

First I should clarify that I agree with the BIS that the abandonment of regulatory zeal, whether through lack of will or legislative fiat, intensified the problems. But the BIS was pretty clear – and I agree with them – that easy money was sufficient to cause the problem, although imprudent regulation shaped it and provided the actual trigger.

To see causation in the particular example you gave, I need to be shown a difference between the US and countries that passed laws similar to the Commodities Future Modernizations Act of 2000 and those that didn’t. I also need to see that there was a difference in different kinds of hard assets that can be attributed to differences in regulation.

It isn’t enough to point to law X and say that a particular kind of investment vehicle would have been illegal. The sainted Canadian banks are in financial hot water now for having lent billions for Teck Cominco to buy Fording Coal mostly with cash. (Thank you, RBC, CIBC and Bank of Montreal; I owned shares in Fording.) They did so assuming that commodities keep rising, a common mistake during a long bubble. How about all of the European banks that are now holding billions in bad Latin American loans to commodity exporters? Were each of those countries’ banks under similar disclosure rules? Would full disclosure have made a bit of difference when the general consensus was that high commodity prices were here to stay?

My logic is simple, and perhaps too simple. You seem to be holding that the Fed could have had a loose money policy, and if only the regulators had not fallen down on the job, all of that money would have found good homes and returned principal and interest to the banks. But taking that reasoning to its logical end ends up with reductio ad absurdem.

If loose money plus regulation can produce high returns with little risk of default, is there no point at which loose money starts to meet bad investments? What if the Commodities Future Modernizations Act of 2000 had not been passed but the Fed had held the interest rate at 1.0% through 2006, veritably flooding the world with dollars? Would vintage 2006 lending be sound on the whole?

If you agree that there is some point at which loose money does matter, how do you know for certain that the Fed didn’t reach that point?

Anonymous, you said, “Negative real rates were amplified by insanely high leverage.”

I do not disagree with that idea, but there are many different ways to lose almost everything when a bubble crashes that don’t require starting off with leverage.

The one-year return for Teck Cominco shareholders is -82.829%. Teck’s bank borrowings were not leveraged. They borrowed money and paid that money to Fording shareholders, dollar for dollar. Then their cash flow to finance the loans dried up.

I don’t disagree that certain ways of losing almost everything were made possible by regulatory failures. All I was saying was that with all of that loose change sloshing around, if not those vehicles it would have been something else, leveraged or not leveraged. Teck shares could have gone twice as high at their height as they did, which would have made its 1-year share price return over -95%.

And I suspect that or something similar is precisely what would have happened. Remember NASDAQ 5,000, before Bush? Remember how eyeballs replaced earnings as a valuation metric? Remember 4 Internet pet food companies with multi-billion dollar valuations each? How insane was all that?

The key to my way of thinking is that there are only so many sound businesses in the world that need to borrow only so much money. When the supply of available money exceeds their needs, the remainder gets squandered – always. The details of how that happens are merely footnotes.

Menzie, may I assume you don’t respond to colonelmoore because he is irrefutable?

bryce: Hardly. But I don’t respond to all posts (I don’t have time to address them all, and also skip those that represent a paradigm so far removed from mine that constructive argument is not possible, e.g., with Marxists, or those who dismiss empirical methods), and in addition I was otherwise occupied on New Year’s Eve.

But for what it’s worth, regarding colonelmoore‘s argument that “blame it on the Fed” is the right way to think, take a look at chart 1.15 in this post, and consider which economies had the lowest real interest rates — it ain’t the one with monetary policy conducted by the Fed.

In addition, I didn’t say the Fed was blameless; rather that given forecasts, policy did not look overly loose, especially given the worries about the hangover from the dot.com bust. Still, I think overleveraging/deregulation/nonregulation had some role — otherwise lax monetary policy should have shown up in inflation, as it has in other instances where negative policy rates were present.

Hence, I think Akerlof and Romer’s view has as much or more plausibility than the “blame it all on monetary policy” perspective.

Menzie,

The chart of real long term interest rates is not very strong evidence in 2 respects: (1) The global credit bubble is a global phenomenon contributed to by most central banks, not just the Fed. (2)Long term rates are the least controlled by central banks & therefore a poor indicator of central bank policy. When the Feds fund rate was 1%, there aren’t too many people who didn’t know it was squirrelly.

Yes I understand the motivation to moderate the Dotcom recession, but it was a mistake. The Dotcom bubble was created by credit expansion; it was like giving the hungover drunk another drink only bigger this time. And here we go with more of the same as we speak…a natural result of fiat or faith-based money rather than market produced money.

There was inflation. It would behoove economist to pay attention to where it was concentrated: things for which people borrow money: commodities, houses, investment assets.

bryce: You’re trying to say the ECB was as expansionary in its policy as the Fed?

Menzie,

No, I’m not saying that. No central bank has tried particularly hard to mimic an interest rate that would reflect the interplay of supply of savings & demand to borrow. My naive impression is that the ECB has tried a little more than the rest of the world.

What I was alluding to is that the PBoC, the Japanese Central Bank, the Korean Central Bank, the Saudi’s, & others have in concerted way bought US & European LONG-TERM debt in the process of preventing appreciation of their currencies. They have distorted long-term interest rates, esp in the US & Europe with their vendor financing. They have thereby distorted their own & our economies in the process of contributing to a global credit bubble.

This is in line with colonelmoore’s penetrating thoughts I believe.

bryce: Oh, I see. The saving glut/conundrum interplay. Well, that’s a plausible argument, although the attribution of depressed interest rates to various factors usually is in the sense of some sort of “residual” in a bond-pricing equation. See [1] [2] [3]. But this view does not preclude the Akerlof-Romer thesis being relevant.

Thank you Menzie for responding to my comments. I always modify my opinions on the basis of data that contradicts them as soon as I understand it. I think that discussions like this are a search for the truth, not a vehicle for grinding a particular political axe. I don’t care who is elected or what credit they get as long as we diagnose the ills correctly. I want to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. I believe firmly that this is your goal as well, and so in that respect we are on the same team.

I believe that someone with only common sense to guide him might be able to see the forest, whereas sometimes economic theories with lots of equations and subscripts can cloud the issues. At the same time, those of us who lack specialized knowledge must be humble enough to learn from those with it.

With that little homily out of the way, I would like to better understand the graph that you showed me. It talks about real long interest rates. This is different from the policy rates referred to in the BIS report. I was also relying on the graph from page 2 of this report http://www.northerntrust.com/library/econ_research/daily/us/dd120705.pdf which shows real policy rates for the US over the decades. Those differ from long rates. It was my understanding that policy rates are a reflection of money creation by the Fed, as it lowers rates as a means of injecting lendable reserves. As such this would be the operative interest rate, not long-term rates. Long-term rates are clouded with such factors as market perceptions of the risk of inflation or deflation for repayment of principal.

I understand that you and others are not holding the Fed blameless. But I am taking a more stringent position. My idea is that had the Fed not flooded markets with too much money the banks would have had to choose their customers more carefully and that they might have preferred solid, Warren Buffett-type borrowers to highly leveraged, speculative investments. It is clear that during the late Greenspan era everyone that wanted credit got it, so clearly there was too much money.

Your other comment that consumer-price inflation would have risen without the role of deregulation and overleveraging is an interesting one that I would like more information on. It is my understanding reinforced by the BIS report that the unique circumstances resulting from influences of the global economy tended to suppress CPI inflation in the beginning even as assets roared ahead. Specifically since wages are 70% of the US economy, such things as NAFTA allowing US manufacturers to set up shop in low-wage Mexico and imports from low-wage countries such as China with fixed exchange rates held down wages. Walmart, a heavy importer from China, became an important part of the economy, placing brutal pressure on other retailers to contain price increases.

Finally, CPI measured only part of what in retrospect was budding inflation. Raw material prices were skyrocketing. (That was attributed to the influence of China, but China was experiencing massive inflation due in part to its fixed exchange rate that made it effectively a dollarized economy.)

I would like everyone to read again the BIS report excerpt in my first post. It states that Occam’s razor says that the current situation can best be explained by too many dollars rather than a miasma of causative factors.