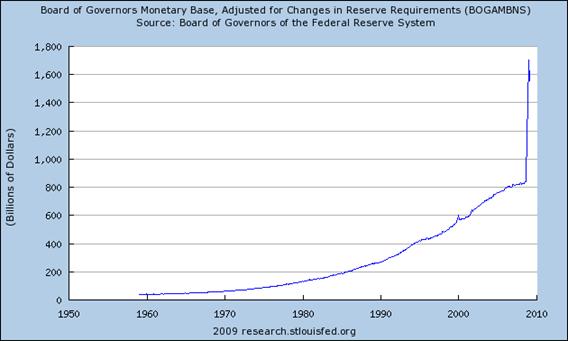

A lot of people have seen this picture of the recent behavior of the monetary base and wondered what it means.

|

To understand the explosion in the monetary base since September, let’s begin with a little background. The Federal Reserve has the ability to purchase assets or make loans with funds (money) that are created by the Fed itself. To buy a billion dollars worth of assets, the Fed doesn’t show up with new cash in a wheelbarrow. Instead the Fed pays for any assets it purchases or loans it extends by crediting the funds that the recipient bank has in an account with the Fed, known as reserve deposits. A bank can later withdraw those deposits in the form of green currency, if it chooses, and that’s the point at which an armored truck from the Fed would be involved with physical delivery of cash.

The monetary base is essentially the sum of (1) the currency that’s been withdrawn from private banks and is being held by the public, (2) the currency that’s sitting in the vaults of private banks that could potentially be withdrawn by the banks’ customers if they wanted, and (3) banks’ reserve deposits, which you could think of as electronic credits for currency that the banks could ask for from the Fed any time the banks choose.

Historically, newly created reserve deposits have usually shown up pretty quickly as currency withdrawn by banks and then by the public. Choosing a pace at which to allow that supply of currency to grow so as to accommodate the increased currency demands from a growing economy without cultivating excessive inflation is one of the main responsibilities of the Fed.

Figure 2 below plots the assorted “factors absorbing reserve funds” from the Fed’s H41 release during the halcyon period from 2003 to the middle of 2007. At that time, currency held by the public was by far the biggest component in the liabilities side of the Fed’s balance sheet, with the currency supply increasing 20% over these 5 years and with temporary seasonal bumps to accommodate the annual Christmas surge in currency demand. Reserve deposits (the sum of the “reserves” and “service” components in Figure 2) were quite minor relative to total quantity of currency in circulation.

|

With this increase in newly created money, the Fed was over this period acquiring assets primarily in the form of short-term Treasury securities, which holdings grew 25% over this 5-year period. The Fed at that time used short-term repurchase agreements as a device for adjusting the supply of reserves on a temporary basis. Note that for each date the height of the components in Figure 3 below (essentially the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet) is exactly equal, by definition, to the height of the liabilities portrayed in the previous Figure 2.

|

Beginning in September 2007, the Fed began a process of systematically changing the nature of its asset holdings. Over the course of the next year, the Fed sold off over $300 billion in Treasury securities (about 40% of its holdings of Treasury securities), and replaced them with $150 billion in direct bank lending in the form of term auction credit, $60 billion in loans to foreign central banks in the form of liquidity swaps, and $100 billion in repurchase agreements, used now not for temporary adjustments but instead as a device to create a market for MBS by accepting alternative assets as collateral.

|

Because the Fed funded those measures through August 2008 by selling off its holdings of Treasuries, there was little effect on either currency in circulation or the monetary base through that time.

|

Beginning in September of 2008, the Fed embarked on a huge expansion in its lending efforts and holdings of alternative assets. The biggest items among assets currently held are $469 billion in term auction credit, $328 billion in currency swaps, $241 billion leant through the CPLF, and $236 billion in mortgage-backed securities now held outright.

|

Where did the Fed get the resources to do all this? In part, it asked the Treasury to borrow on its behalf, represented by the pale yellow region in Figure 7 below, and a sum that last week amounted to a quarter trillion dollars. Note that magnitude is not part of the monetary base drawn in Figure 1. Some of the Fed expansion has shown up as additional currency held by the public, which made a modest contribution to the explosion of the monetary base seen in Figure 1. But by far the biggest factor was a 100-fold increase in excess reserves, the green region in Figure 7. These excess reserves mean that for the most part, banks are just sitting on the newly created reserve deposits, holding these funds idle at the end of each day rather than trying to invest them anywhere.

|

That idleness, as I read the situation, was something the Fed initially actually wanted, and deliberately cultivated by choosing to pay an interest rate on excess reserves that is equal to what banks could expect to obtain by lending them overnight. As long as banks do just sit on these excess reserves, the Fed has found close to a trillion dollars it can use for the various targeted programs.

But what would happen if those electronic credits start to be redeemed for actual cash? Then we would have a concern, and the Fed would need to call the reserves back in by selling assets or failing to renew loans. But that presents a potential problem, as noted by Charles Plosser, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia:

It is true that a number of the Fed’s new programs will unwind naturally and fairly quickly as they are terminated because they involve primarily short-term assets. Yet we must anticipate that special interests and political pressures may make it harder to terminate these programs in a timely manner, thus making it difficult to shrink our balance sheet when the time comes. Moreover, some of these programs involve longer-term assets– like the agency MBS. Such assets may prove difficult to sell for an extended period of time if markets are viewed as “fragile” or specific interest groups are strongly opposed, which could prove very damaging to our longer-term objective of price stability.

Last Monday’s joint statement by the Treasury and the Fed indicated that the plan is for the worst of the Fed’s assets (reported as “Maiden Lane” and part of the “AIG” sums in Figure 4) to be taken over by the Treasury, and Plosser for one wants the Treasury to take all the non-Treasury assets off the Fed’s balance sheet. But as the Fed has declared its intention to raise its MBS holdings to $1.25 trillion it seems the current plan calls for more, not less of non-Treasury assets. And the following clause in the joint Fed-Treasury statement suggests that perhaps the Fed intends this, like most of the previous balance sheet changes, to not be allowed to impact total currency in circulation:

the Treasury and the Federal Reserve are seeking legislative action to provide additional tools the Federal Reserve can use to sterilize the effects of its lending or securities purchases on the supply of bank reserves.

John Jansen (hat tip: Tim Duy) construes that clause to mean that the Fed is going to request the ability to borrow directly as well as for exemption of any borrowing done by the Treasury on behalf of the Fed from the congressional debt ceiling. Also via Tim, FRB San Francisco President Janet Yellen offers this elaboration:

As the economy recovers, the Fed will eventually have to reduce the quantity of excess reserves. To some extent, this will occur naturally as markets heal and some programs consequently shrink. It can also be accomplished, in part, through outright asset sales. And finally, several exit strategies may be available that would allow the Fed to tighten monetary policy even as it maintains a large balance sheet to support credit markets. Indeed, the joint Treasury-Fed statement indicated that legislation will be sought to provide such tools. One possibility is that Congress could give the Fed the authority to issue interest-bearing debt in addition to currency and bank reserves. Issuing such debt would reduce the volume of reserves in the financial system and push up the funds rate without shrinking the total size of our balance sheet.

In other words, if the Fed decides that, as a result of inflationary pressures, it needs to undo some of the expansion in its liabilities at a time when it is not prepared to unwind its asset positions, Plan B is for the Fed to borrow directly from the public.

Which brings me back to the original question. Does the explosive growth of the monetary base in Figure 1 imply uncontrollable inflationary pressures? My answer: not yet, but stay tuned.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

economics,

Federal Reserve,

term auction facility,

deflation,

inflation,

credit crunch

“uncontrollable inflationary pressures”? as in 3% inflation per annum, 30% inflation per annum, 300% inflation per annum,…?

A very useful summary!

“But what would happen if those electronic credits start to be redeemed for actual cash?”

How relevant is the above question? In my opinion the answer is the key factor separating people worried about inflation when they see Figure 1 from those only worried about deflation. The latter group tends to believe the opportunities to profitably use that cash (loans, investments, etc) will be scarce until a LOT more deleveraging and balance sheet healing is complete, and that the odds are this will take a while.

The various methods to sterilize the effects of the Fed’s balance sheet expansion have some tradeoffs but are not completely different:

1. Paying interest on reserves is a bit like issuing ultra-short-duration bonds to a “private” group of investors, i.e., only banks.

2. Borrowing from the public would offer the Fed flexible durations and a wider set of investors. #1 essentially segregates the new currency and the sterilization “bonds” from the rest of the market, while #2 pools them together and has the banks bidding for the “sterilization bonds” within the broader market.

3. Having the Treasury issue the bonds (e.g., Treasury Supplemental Financing program) is very like #2 but requires the Fed to work with the treasury rather than be in total control, which probably explains why they gave it up?

So the mix of methods seems to offer more flexibility but not radically change the situation. Correct me if I’m wrong.

cbe: Figure 1 portrays an instantaneous doubling in the monetary base, suggesting that we are talking here about something on the order of a doubling in the price level or 100% inflation rate.

hbl: I take the question on the table to be whether the remix and expansion on the asset side is the best policy.

You mean, Can Ben bubble down as well as he bubbles up?

Excellent post Dr. Hamilton. I have a couple of questions however. You mention this: But what would happen if those electronic credits start to be redeemed for actual cash? Then we would have a concern, and the Fed would need to call the reserves back in by selling assets or failing to renew loans…

Would not this represent banks beginning to actually lend money, which is something that has been encouraged for some time? Is it really the *rate* at which these credits are being redeemed that is of concern? Even if banks begin to lend and people are spending the newly created money, wouldn’t there still be an overall lag in the velocity of money accelerating? I’m thinking that you would need to actually see empirical inflation occurring before you would want to do something about it. Also, if the Fed wanted to put a brake on lending, couldn’t it just charge a much higher interest rate for reserve deposits to accomplish that goal?

The excess reserves trouble me and I would appreciate it if someone could answer these questions:

How did the banks get the reserves – through the purchase by the Fed of various assets on the bank’s balance sheets?

Why aren’t the banks lending this money? Is it because of a lack of credit-worthy borrowers? We constantly hear that credit markets are frozen. Is it a case they simply don’t exist at reasonable prices for the risk?

I know from earlier study that the Fed would force a ‘haircut’ on borrowers. I assume they have done this for the ‘toxic’ assets they have acquired. Still, will their balance sheet suffer when they have to unwind these or accept defaults?

Otherwise, thank you for a clear explanation of a someone opaque topic for a civilian.

Correction:

Also, if the Fed wanted to put a brake on lending, couldn’t it just pay a much higher interest rate for reserve deposits to accomplish that goal?

The fed is not a government agency. How plausible us it to fund itself through debt issuance? Does it really make any difference if it borrows in the name of the treasury or its own when repayment of this debt is only possible through money printing?

This is just kicking the can down the road.

The Fed will not be able to put on the brakes to avoid significant inflation because the level of indebtedness–whose proper liquidation the Fed & Treasury are presently preventing–is so high (350% GDP!) that market interest rates would be brutally punishing.

Instead of bankruptcies, the debt is being shifted onto taxpayers. (The inflation tax will catch the many who don’t pay any Federal tax.) Yet to be bailed are FDIC, Pension Guarantee, Medicare & others.

We are governed by people who don’t believe bankrupt companies should be allowed to go bankrupt. If you don’t believe bankrupt companies should experience the truth, you don’t believe in truth or freedom. You think you know better.

Dr. Hamilton, do you think that the Fed’s initiatives will pull us out, or do you think that the government response is doomed to failure as expressed by the recent president of the IMF, found here

http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200905/imf-advice

This is a crap blog. Stop posting and leave the web for those who try. You add nothing but a blurb and links to competent bloggers.

Eternal sunshine has melted your brains. You are a disgrace to the profession.

The dollar is certainly being destroyed here and I agree with Ron Paul that the Feds need to be audited since they are causing the US dollar to weaken tremendously (and the world agrees)

15 year depression

Nice explanation. Might be useful to see how the money supply reacted to the increase in the base; Fred database has a chart here

If the fed had the power to issue interest bearing debt to soak up excess liquidity in the system, how would that debt be any different from treasury debt (in practical function)? Looks to be the same thing in the end. No magic bullet.

Imagine the Fed holding long assets at average 4% coupon, and needing to sell debt to the public market to get things under control. In a high inflation scenario, the market might demand much higher interest: ie 7%+. Suddenly the Fed is trapped.

Couldn’t the Fed just raise the banks’ required reserve ratio from 10% to 20% if necessary to slow down lending?

Isn’t the solution simple?

1. The Fed should sell its crappy assets to the Treasury, receiving as payment newly issued Treasury securities.

2 The Fed should then start selling its replenished supply of Treasury securities to drain reserves.

If that doesn’t do the trick, the Fed can raise reserve requirements, raise interest rates on its loan programs, and sell off its commercial paper portfolio. And the Treasury should raise taxes on private wealth, high incomes, and corporate profits to compensate for any loss incurred on the crappy assets it acquires from the Fed.

Wonderful post! Thank you very much.

Good post and speculation about the Fed exit strategy. But several nagging questions remain. With $.8tn in excess reserves, commercial bank lending should be exploding but hasn’t. The interest the Fed pays on the excess reserves is too low to explain this. Of course, the reserves may be–and probably will be–used subsequently to buy up the incoming new Treasuries for deficit finance, expanding M2 and reducing potential crowding-out (emphasis on “potential”–right now there’s little reason for business investment to expand to prior levels). But why wouldn’t the excess reserves already be gone from new lending before the Treasury financing needs arrive?

Very interesting, thank you.

I think the reason banks are not lending is:

1.as some one pointed out earlier…there are not many credit worthy companies/consumers seeking loans, its almost shocking switch from the way these things were working just 1-2 years back.

everyone was getting loan for anything they wanted….but now the velocity of money has died.

2.If i am not wrong, consumers and companies balance sheets are in pretty bad shape…and it will take some wage inflation and-or price inflation before they will have any borrowing capacity

unless banks balance sheets are cleaned up by subsidising with the unspoken clause being that they have to take risk and lend to credit risk consumers/companies…with the sole purpose of restaring the debt driven part of the economy to help the stimulus spending/empployment creation part of the economy.

The back of the TIPs implied inflation curve is already around 2% – the Fed’s target. Will the Fed choose to ignore this indicator now that it is inconvenient? probably.

Congratulations Professor + thanks, you did a good job.

Guess you are a good teacher …

Can you please help explain the role of the velocity of money and the money multiplier, what they are now, how they might change, and what the impact would be?

Econobrowser…”Choosing a pace at which to allow that supply of currency to grow so as to accommodate the increased currency demands from a growing economy without cultivating excessive inflation is one of the main responsibilities of the Fed.”

Unfortunately, the Fed does not distribute the newly created money evenly among all consumers. The Fed distributes the new money to a few, which winds up concentrating wealth mainly in the financial sector. This is the biggest flaw of the current system. The consumer does not get a seat at the open market table, only financial institutions et al do. Financial sector leverage builds up to unstable levels, and consumers lose purchasing power over time.

Why aren’t the banks lending this money? Is it because of a lack of credit-worthy borrowers?

seconding techy and others, i think the reason is that few in their right mind would increase their debt load at this juncture. loan demand is brutal — C&I, CRE, consumer all, with a bounceback in mortgage thanks to the ongoing refi craze, which of course is not significant debt creation. loans to households are actually contracting QoQ for the first time since ww2. and that means excess reserves have no path out of the banks — excepting, of course, the fed or the treasury.

i’m sure the fed did want to puff up their balance sheet by paying interest on excess reserves, but the banks would surely be making loans at the much higher spreads on offer if they had (in aggregate) decent loan prospects.

this is a hell of a problem for the fed. there is no monetary policy without aggregate loan demand.

Suppose the Fed decides to buy assets from depository institutions (eg commercial banks).

The Fed buys the asset (let us say worth $1000) from the bank and then makes a payment to the bank crediting the bank’s reserve account by the same amount of the purchase.

What are the balance sheet entries? We can use T-accounts to reflect these changes.

First, for the Fed. The Fed increases its assets holdings by $1000 and at the same time its liabilities are increased by $1000.

Now, for the commercial bank. In the first step the bank sells the asset to the Fed in exchange for reserves. The Fed exchanges non- or low interest-bearing assets (which we might simply think of as reserve balances in the commercial banks) for higher yielding and longer term assets (securities or any other asset).

The commercial banks get a new deposit (central bank funds) and they reduce their holdings of the asset they sell.

(Recall that the government spends by creating deposits in the private banking system).

This is what happened during the financial crisis when the Fed decided to buy assets from the banking system. Banks started to have non-interest bearing excess reserves. They tried to lend them on the interbank market. This put a downward pressure on the overnight interest rate. Note that the Fed has to keep the overnight interest rate close to the target. To accomplish this, they started to sell bonds to drain reserves from the banking system and hit the ffr target. At some point they ran out of bonds to drain these reserves. What did the Fed do? They asked the Treasury to issue more T-bills to, basically, help the Fed drain the excess reserves.

Later on, they recognized that if they started paying interest on reserves that would put a ‘floor’ for the overnight interest rate.

This means that the overnight interest rate can not go any lower than the rate the Fed pays on them because banks will not lend reserves on the interbank market and accept a rate lower than the one that the Fed pays.

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the banks capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves. Bank lending is not reserve constrained. The reason why commercial banks are currently not lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers.

Check also Warren Mosler’ blog http://www.moslereconomics.com/

Comment to Joseph:

The Fed could do this but it would have no immediate effect other than to transfer reserves from the excess to the required category.

As to “slow down lending”, isn’t the opposite the problem? The authorities are trying to encourage lending.

Fed issuing debt reminds me of the Argentina’s central bank in the hyperinflationary episode in the late 1980’s. The bank issued debt and got itself trapped in a situation where it had to print to pay interest on it’s debt. I worry that the current situation could go the same way if fiscal pressures keep the treasury from supporting the Fed. (I doubt we would get hyperinflation but we might get very high inflation before necessary fiscal reforms were made)

This is a spectacularly good exposition, with unmatched graphs. Blogging everywhere should declare a holiday and study it.

Some minor quibbles:

“But what would happen if those electronic credits start to be redeemed for actual cash?”

Why would you plausibly expect the public to want to change the trajectory for holding currency in such an abruptly disproportionate fashion?

And

“The following clause in the joint Fed-Treasury statement suggests that perhaps the Fed intends this, like most of the previous balance sheet changes, to not be allowed to impact total currency in circulation”

What direct control does the Fed have over the public demand for currency? None. Not directly.

Sterilization alternatives are a requirement given the likelihood for expansion. They are not an alternative to currency issuance, because the Fed doesn’t control the demand for currency.

JKH makes a great point worthy of further study. At what rate do we expect the banks to start lending again. This involves two considerations: 1) When can we expect asset deflation to cease; and 2) when can investors begin to expect satisfactory returns on borrowed money. The answer to 1) IMHO is now. The fiscal stimulus, low energy prices and low mortgage rates seem to have placed a floor on prices for now. But regarding 2), IMHO investors will not see satisfactory returns because personal income is not rising, i.e. too many people entering the work force and too little income to spread around. The reason IMHO is the consumer is still working off debt; also production has travelled overseas. We can only sell only so much pizza to each other (an over-used simile, sorry).

I have a friend who is always saying,”…you can’t solve a debt problem with debt.” The same is true with a liquidity problem. You can’t solve a liquidity problem with more liquidity.

Another excellent post, Professor!

JDH wrote:

b”…by far the biggest factor was a 100-fold increase in excess reserves, the green region in Figure 7. These excess reserves mean that for the most part, banks are just sitting on the newly created reserve deposits, holding these funds idle at the end of each day rather than trying to invest them anywhere.

That idleness, as I read the situation, was something the Fed initially actually wanted, and deliberately cultivated by choosing to pay an interest rate on excess reserves that is equal to what banks could expect to obtain by lending them overnight. As long as banks do just sit on these excess reserves, the Fed has found close to a trillion dollars it can use for the various targeted programs.

Professor,

Why? If the desire of the FED is to stimulate the economy doesn’t this actually have the effect of hoarding the new currency? Where is the stimulus? What good do $trillions do the FED if it is locked up in the banks?

Foreigners, not Americans, hold most of the US dollar hard cash. The chart spike mostly reflects freightened foreigners rushing to their banks to withdraw dollars to stuff under their mattresses.

Professor,

Quite honestly, the only reason I am not scared to death by looking at the unprecedented expansion of Fed balance sheet is that Ben Bernanke is in charge of the fed, and I feel quite confident that he is thinking ahead of how to drain all this expansion from the balance sheet.

That said, I have three questions:

* What is the probability that the Fed will end up issuing Fed Bonds and make the banks buy those?

* What about other countries where Central bankers have expanded balance sheets rapidly? What is the chance that they will be able to escape rapid escalation in inflation as the economy begins to recover, when it does indeed recover?

* Even though we may not be facing a hyper-inflationary scenario, should we still not be stoking up on TIPS, considering that even now they are factoring in a very low inflation for a decade?

The Fed needs to start slowly increasing the FF rate back up to about 2%. That is still pretty low, but the present 0-.25% is ridiculous, and should only be sustained for a couple of months in the case of extreme crisis. I think the fear has moderated, and it is time to get back to about 2%.

Whenever there is a chart like that (Nasdaq in March 2000, China’s stock market in 2007, oil prices), we know what happens next.

So we either have hyperinflation, or the Fed contracts the money supply enough to not cause assets to crash down too sharply.

It is a tightrope act if there ever was one.

deficit spending adds net financial assets to the private/non govt. sectors that are equal to the size of the deficit.

Govt deficit= tsy secs outstanding+reserves at the Fed+ cash in circulation

The Fed controls the mix, but not the total quantity which always equals the cumulative deficits.

The mix of tsy secs, reserves, and cash is of no economic consequence beyond that of the resulting term structure of rates which are determined by the Fed as it manipulates the mix.

For the Fed,it’s about ‘price’ (interest rates) and not ‘quantity’

http://www.moslereconomics.com http://www.mosler2012.com

Doc at the Radar Station and perhaps also JKH: Yes, one scenario is indeed the gradual improvement picture, and I agree that this scenario is one in which the Fed could ease out of its current positions. But another more troubling scenario could come through a sudden shift in expectations, manifest as a currency run and commodity price spike.

Ian Nunn: Any time the Fed buys an asset or makes a loan it creates reserve deposits. That is how the funds get delivered. As for why banks don’t lend, the rate on fed funds leant is practically zero and by policy is no higher than the rate paid to banks by the Fed for not lending those funds. That is one of the reasons I think we’d be better off with a situation of 3% inflation, a modest but nonzero fed funds rate, and zero interest paid on excess reserves. See also useful perspectives on your questions from many of the other commenters.

Dumb Joe 6-P: I do not know the answer to your question, but would point out there are possibilities in between the extremes you pose, such as, we may have averted a disaster (with or without the Fed measures), but recovery will be slow and painful.

Michael Krause: Yes, Fed debt is like Treasury debt, but like Treasury debt, adding more raises questions about how it’s going to be repaid. I do not think we want to cultivate even more concerns that the Fed will be forced to inflate its way out of the current situation.

Steve: Velocity refers to the ratio of a number like GDP to a monetary aggregate. Thus if the base behaves as in Figure 1 and GDP does nothing, velocity is plunging. Money multipliers refer to the ratio of a broader aggregate like M2 to the monetary base. Again, since M2 is not growing like Figure 1, these multipliers are also plunging. Some people think of either velocity or multipliers as fairly stable parameters but they’re clearly not in the current situation.

Felipe: I don’t see that the observed timing fits your story. Check Figures 4 and 5. The Fed had sold off most of their Treasuries before September 2008, and there was no bulge in excess reserves before that date.

DickF: My position is that paying an interest rate on excess reserves equal to the target fed funds rate was a policy mistake. I believe what the Fed may have been thinking was that they could fund an arbitrarily large amount of lending themselves if they had the flexibility to create new reserve deposits without limit. But if anyone has a better explanation for why the Fed should pay interest on reserves, I’d be interested to hear it.

John Booke: No, the spike in the monetary base specifically refers to cash that nobody has withdrawn and nobody has stuffed in a mattress. It represents credits for cash that the banks don’t withdraw and leave in their accounts at the end of the day without trying to lend them out.

Why should the Fed pay interest on reserves?

Scott T. Fullwiler sheds light on this point:

“…the more direct and more efficient method of interest rate support would be for the Fed to simply pay interest on reserve balances. With interest-bearing reserve balances (IBRBs), absent offsetting Treasury or Fed operations to drain excess balances created by a deficit, the federal funds rate would simply settle at the rate paid on reserve balances. The nature of Treasury bond sales as offsetting, interest-rate support rather than finance would be obvious. While the private sector is offered an interest-bearing liability of the government in the presence of a deficit to support a non-zero interest rate target, this does not necessitate that the Treasury sells bonds.

Such actions are sometimes feared to undermine the independence of monetary policy by creating excess balances, though with IBRBs replacing bond sales the Fed’s independence and ability to exogenously adjust the federal funds rate target would be uncompromised and would simply require increasing or decreasing the rate paid on IBRBs. Regardless of the quantity of excess balances, the federal funds rate would not fall below this rate and would continue to influence other rates in the economy via arbitrage since banks use reserve balances to settle their customers’ tax liabilities (Fullwiler 2004). Holders of deposits so desiring could convert to short-term, private liabilities -just as they can now-the rates for which would be set primarily via arbitrage with the Fed’s target. Long-term rates-just as now-would be largely dependent upon the current and expected future paths of short term rates. Those desiring fixed- instead of flexible-rate investments-perhaps banks holding IBRBs-could do so through swaps that would be priced similarly. Without Treasuries, government agency securities and swaps could emerge as benchmarks for pricing of private assets, as is increasingly the case already and for which they are better suited than Treasuries anyway. In sum, with a deficit the transmission of monetary policy via IBRBs is identical to that with non-interest bearing reserve balances (NIBRBs) and bond sales to drain excess balances.

With IBRBs, all Treasury securities could eventually be replaced; the interest rate on the national debt would then be the rate paid on IBRBs. Treasury securities themselves are simply fixed-rate liabilities and from the private sector’s perspective not functionally different from IBRBs aside from the flexible-rate nature of the latter. Note that consideration of IBRBs demonstrates how interest on Treasury debt is determined: with IBRBs and no securities issued, the interest rate is the rate paid on IBRBs; where short-term securities are issued, as above these rates are set via arbitrage with the Fed’s target; as longer maturities are issued, again as above these rates are set largely via arbitrage with the expected path of the Fed’s target. The ‘crowding out’ view of the loanable funds market is irrelevant; the rates on various types of Treasury debt are set by the current and expected paths of monetary policy and according to liquidity premia on fixed-rate debt of increasing maturity. Since long-term rates are normally higher than short-term rates, total interest on the national debt would be significantly reduced if IBRBs eventually replaced Treasuries. Those-like the Treasury-fearful that IBRBs would reduce seigniorage income neglect that this would be far outweighed by the reduction in total interest paid on a national debt increasingly held as IBRBs. Indeed, there is no inherent reason for Treasury liabilities to exist across the entire term structure except as support operations for longer-term rates (Mitchell and Mosler 2002).”

Fullwiler, Scott T. “Paying Interest on Reserve Balances: It’s More Significant Than You Think.” Journal of Economic Issues 39 (2) (June): 543-550.

Available at http://www.cfeps.org/pubs/wp/wp38.html

Hoover in his day also had the printing presses going, however the banks then would not lend either. He saw it was not stimulating the economy and then he stopped printing. Did he just need to keep the printing presses going for a little longer?

Felipe quotes Scott Fullwiler as saying, “With interest-bearing reserve balances (IBRBs), absent offsetting Treasury or Fed operations to drain excess balances created by a deficit, the federal funds rate would simply settle at the rate paid on reserve balances.” But this is not correct. Holding excess reserves is risk free, lending them on the fed funds market is not. Why would a bank choose to make a risky loan at the same rate it could earn from a risk-free alternative to the funds? Moreover, insofar as the procedure is being implemented by having the interest paid on excess reserves be the same as the target rate for the fed funds rate, it intentionally in my mind takes away any incentive for banks to lend those available overnight funds.

Professor – GREAT explanation, thank you!

And – your explanation of the Fed’s interest-paying policy makes good sense. Their intention appears to have been to:

1) Take on a load of ‘less liquid’ assets from banks (and failed companies – Bear, AIG!)

2) Limit the short-term inflationary effects of these actions by providing incentive for the banks to keep cash in Reserve.

Early on, it appears that the Fed mistook what is actually a crisis of insolvency, for one of illiquidity. Anna Schwartz put this forth in her October opinion piece in the WSJ.

A question on Federal Reserve Bonds – what is the point? A Federal Reserve Note is a claim, which gives the bearer the right to bring it in to a Federal Reserve bank and exchange it for… another Federal Reserve Note. A Fed Bond would be the same kind of liability (albiet also paying interest… in Federal Reserve Notes!). Really, it’s just interest-paying M0, no?

What would distinguish Fed Bonds, in practice, from currency?

Is this simply for the purpose of achieving greater independence from Treasury?

The Fed should STOP paying interest on reserves. What we are going through is a direct result of this policy – of their deliberate refusal to reflate. They did this in 1936 and are doing it again. It is an utter and gross failure – as it was with Andrew Mellon. What we are going through is not due to some big market or debt failure. It is due to the direct refusal of the Fed to expand the currency base sufficiently – a direct desire on their part to have deflation. As this blog post makes completely clear. By the Taylor rule interest rates are now 6 full percent too high – and what is the Fed doing about this? Nothing whatever. It is a gross failure.

The deflationists are running the show. We are our own Andrew Mellon now – and it is totally insane.

For a contrary point of view – see here:

http://blogsandwikis.bentley.edu/themoneyillusion/?p=753

or here:

http://www.americanthinker.com/2009/03/what_president_obama_should_kn.html

JimP – respectfully – the opposite is true. Bernanke is terrified of deflation, he sees it in every shadow, and so he has lowered interest rates to zero and is now pursuing direct monetization of debt to achieve the same result as the necessary additional reductions (because he can’t lower nominal short-term rates to negative territory).

At some point the Fed did realize the danger of deflation and is doing everything they can to fight it. The smart-money sees this as well – otherwise, Treasurys would not be selling at zero-yield.

Unfortunately, the scale of the debt unwind (private debt is 300% of GDP, some $25 TRILLION more than what would be the historic mean of 150%) is such that even Ben does not have a big enough helicopter to counteract the deflationary forces.

We may (probably) have inflation in our future, but, it is a longer way off than many might think.

Please forgive the self-promotion:

http://macrobuddies.blogspot.com/2008/12/deflation-blues.html

http://macrobuddies.blogspot.com/2009/03/keynesianism-is-tired.html

Murph –

I certainly do agree with your blog on the profound danger of deflation. But I do not agree that Bernanke is doing much of anything to counter it.

Paying interest on reserves is a radical new policy by the Fed, and in the Hall paper where that policy is first described it is clearly explained that this is a deflationary policy.

He has failed to anchor inflationary expectations, which he could do – by announcing a price level target – and then committing to get it. That is the whole point of all the posts on this blog:

http://blogsandwikis.bentley.edu/themoneyillusion/?p=411

Take a look at this post. I would be interested in your reaction.

Your blog clearly does recognize the deep danger of deflation. I am sure Bernanke does too. But he is not doing the most effective things he could do to counter it.

JDH: The observed timing does fits the story. Your Figures 4 and 5 are not updated.

Even the chairman of the Fed recognized that!

According to Bernanke,

“…our liquidity provision had begun to run ahead of our ability to absorb excess reserves

held by the banking system, leading the effective funds rate, on many days, to fall below the target set by the Federal Open Market Committee…the Federal Reserve [will start]to pay interest on balances that depository institutions hold in their accounts at the Federal Reserve Banks.

Paying interest on reserves should allow us to better control the federal funds rate, as banks are unlikely to lend overnight balances at a rate lower than they can receive from the Fed;

thus, the payment of interest on reserves should set a floor for the funds rate over the day. With this step, our lending facilities may be more easily expanded as necessary.” (Bernankes comments on October 7)

How does the Fed absorbs excess reserves held by the banking system? One way is by selling bonds! Bonds sales drain reserves and help the Fed hit the FFR close to the target.

The point of paying interest on reserves is quite clear from Bernanke’s comment.

JDH wrote:

DickF: My position is that paying an interest rate on excess reserves equal to the target fed funds rate was a policy mistake. I believe what the Fed may have been thinking was that they could fund an arbitrarily large amount of lending themselves if they had the flexibility to create new reserve deposits without limit. But if anyone has a better explanation for why the Fed should pay interest on reserves, I’d be interested to hear it.

Excellent answer Professor. You have addressed my point directly and I agree with you.

You may not want to specualte on this but do you believe that Bernanke understands that this was a policy mistake?

“I believe what the Fed may have been thinking was that they could fund an arbitrarily large amount of lending themselves if they had the flexibility to create new reserve deposits without limit. But if anyone has a better explanation for why the Fed should pay interest on reserves, I’d be interested to hear it.”

That’s the correct explanation for why they’re doing it in my view.

And it works.

But it doesn’t explain why you think it’s a mistake.

“But this is not correct. Holding excess reserves is risk free, lending them on the fed funds market is not. Why would a bank choose to make a risky loan at the same rate it could earn from a risk-free alternative to the funds? Moreover, insofar as the procedure is being implemented by having the interest paid on excess reserves be the same as the target rate for the fed funds rate, it intentionally in my mind takes away any incentive for banks to lend those available overnight funds.”

Not true. The Fed can easily adjust the interest rate on reserves to create a spread against the target Fed funds rate, making the funds rate marginally more attractive for lending as necessary. The Fed has made it clear it will be flexible on the required spread as monetary conditions change.

Glad you are on the job, Professor, watching the Fed’s moves for the potential to crank up consumer prices.

Tell us hoi polloi when it is time to riot, please!

Me, I’m concerned now, hence, my long-term portfolio is 100% gold/silver stocks/bullion.

Jim,

Back in November a prominent monetary economist whom I shall not name here went through the Fed balance sheet and the changes in the previous two months. This person argued that a substantial portion of the currency swap with the ECB was directed at helping them deal with the collapse of SIVs in Europe, which amounted to something like $600 billion, which looks about like the size of that increase in currency swaps. Do you have any information on this matter?

It would appear that the scale of the currency swaps have been wound down somewhat, although it is my understanding they were extended in early February, with some observers grumbling that these swaps were interfering with forex markets, presumably putting downward pressure on the dollar and thus adding potentially to inflationary pressure in the US.

My opinion, is that the FED’s doubling of reserve deposits, has improved the banking industry’s ability to weather the inevitable losses in ABS, private equity, and consumer loans. It should be viewed as a direct subsidy to banks, not as an economic stimulous measure. Because US equity and RE market losses are approaching $17 Trillion, the injection of $1T in the FED’s balance sheet, doesn’t come close to filling in the hole. The 350% Total credit debt/GDP ratio, also indicates that there is little or no ability to expand liquidity via securitization.

I see little or no ability for the FED or Treasury to inflate the dollar until something close to real market clearing prices are placed on bank held securities. This is sure to be a long drawn-out affair, due to the yet to be realized losses of ARMs, commercial property, and private equity leverage; as well as delayed bank mark-to-market accounting protocols.

The leverage in the system has to be reduced, before the economy has a chance to grow. That can either occur by taxing the economy to cover non-performing debts until they are retired, or by realizing losses quickly and liquidating the debt… It looks like we will be taking the hybrid approach- throwing enough subsidies out there to delay the demise of the incumbants for few more months (GM & Chrysler), or for a year or two (Citi, BOA, etc.), rather than facing the music now.

The more interesting story, will be the pressure by the European Commission, Geithner, progressives, and dissaffected conservatives towards controlling and regulating the derivative markets and shadow banking system. That issue expedited the rampant fraud and asset bubbles over the last 20 years, and will define whether there will be corrective action or “business as usual” in banking and finance. My bias is that “confidence” will not return to the financial system, and significant investments will not be made until governmental action is taken to prevent looting.

While it may seem as though there is little difference between having the Treasury issue interest bearing notes and having the Fed do it, there is a huge difference as far as checks and balances.

The Federal Reserve is supposed to be responsible for monetary policy, and monetary policy only. The ability to issue money is an extraordinary power, which requires clear limits in order to prevent it’s abuse. The clear limit here has always been that they can issue as much currency as they like, but they can’t decide what to spend it on. The Fed should always be limited to spending that currency on repurchasing Federal debts already issued or guaranteed by the US Treasury. Only the Congress and the Executive Branch should have the power to obligate US taxpayers for their debts.

This is also why the Fed should not be allowed to pay interest on reserve deposits, if doing so is indeed similar to issuing Treasuries. The key difference here is that Treasuries are in fact issued by Treasury, not by representatives of bankers deciding when and how much to pay themselves.

It may well be that it is necessary for taxpayers to provide some direct support for banks at this time, in order to avert a greater crisis. And it may well be that this is a difficult sell amongst democratically elected representatives, who will have to explain this to voters. But this is what democracy requires. The crisis of the moment is a poor excuse for the subversion of democratic governance and important checks and balances against corruption and the abuse of power.

Execellent post!

I agree with anon that your explanation is pretty good.

“I believe what the Fed may have been thinking was that they could fund an arbitrarily large amount of lending themselves if they had the flexibility to create new reserve deposits without limit. But if anyone has a better explanation for why the Fed should pay interest on reserves, I’d be interested to hear it.”

Not trying to give a different explanation, here is the timeline: the New York Fed could not keep the fed funds rate at target the effective rate was under the target considerably — fed got the approval to pay interest on excess reserve, presumeably created a floor for the fed funds rate — they first set the interest rate 25-75(?) bps below the target rate, but (here came the most puzzling part) the fed funds rate fell under the interest rate on excess reserve almost everyday — so they changed (here came the crazy part) the rate to something like “average effective fed funds rate for the maintainous period”, basically not only defined the puzzle away (and deprived researchers a clue to see what was wrong with the funding markets), but also made it impossible for the interest payment on excess reserve to act as a floor for the fed funds rate, which they worked so hard to get. They then just quickly sent the target rate to under 25 bps, so everything are pacted at zero so none of this matters.

A separate point: can all of these just simply counter-productive? I heard all of these excess reserve are creating headaches for banks because they make banks capital ratios look worse. Further, as FDIC fees are based on assets, the idle excess reserves are costly to banks. Similarly, low interest rates significantly reduce the interest income for retirees, which put downward pressure on consumption. And few people are enjoying this low interest rate — spreads are wide.

Another crazy thought: the reason banks continue to lend less may be because there are fewer credit-worthy borrowers around? Investment grade corporate have no problem getting funding: first quarter issuance of non-financial company bonds was more than triple that of the same peiord last year. The average yields was only 6.9, compared with 6.2 average for the 10-year through Jly 2007.

When the Federal Reserve increases the monetary base, interest rates go down, which has been the strategy of the Fed during the current global economic downturn. The interest rates go down when the Fed increases the monetary base because the price of money goes down, therefore there is more money available. When the interest rate goes down, there is less demand then for U.S. dollars, so the dollar then depreciates. Having the current Fed interest in the U.S. be close to zero, this helps spur investment in the country because businesses can finance new equipment at a lower interest rate. With the increase in the monetary base, people then have more funds to pay for goods and services; and to meet this higher demand, producers hire more workers, and wages rise to attract more workers or compensate workers for overtime. In the short run, prices are sticky and there is no change. But in the long run, prices of outputs will then eventually rise to compensate for these higher costs and this money supply would then decrease due to the adjustment of the economy.