Often after a sharp economic downturn we observe an equally dramatic recovery. But nobody can claim to be seeing that so far in the currently available data.

Since the beginning of April, we’ve been discussing one potentially favorable indicator in the form of new claims for unemployment insurance. In each of the last 6 recessions, the 4-week average of this series reached a peak less than 8 weeks before the economic recovery began. None of the readings over the last 8 weeks exceeded the value reached April 9, consistent with the hypothesis that we are past the peak in new claims for this cycle.

|

On the other hand, the most recent values for initial unemployment claims have not shown further improvements. Although the number released on Thursday was widely reported in the press as a drop in the number of new claims, it actually resulted in a slight increase in the 4-week average, putting the latter pretty much back where it was 4 weeks ago. If we were really beginning a recovery similar to that experienced in previous episodes, we should be seeing sharper drops in this number at this point.

|

And if an economic recovery had begun at this point, we should be seeing confirmation in a number of other indicators. The downturn in business fixed investment gained momentum late in this cycle, leading me to expect the recovery to begin with growth in personal consumption and housing.

|

One indicator I’m watching in particular is new car sales, since current sales are unsustainably low given scrappage of old vehicles. But I see little sunshine in the May auto sales numbers. Total light vehicles sold in the U.S. had been down 34% between April 2008 and April 2009, and were down that same 34% between May 2008 and May 2009.

|

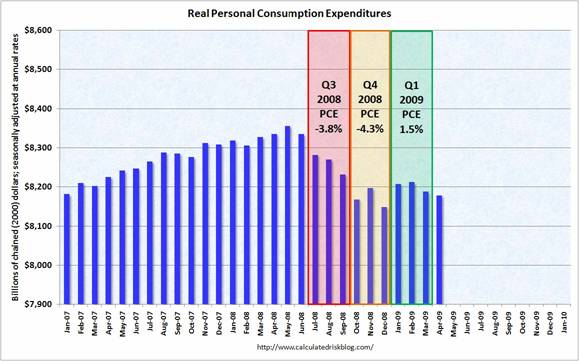

We did now get two consecutive monthly increases in disposable personal income, and that’s certainly good news. But it’s interesting and important that real personal consumption expenditures actually fell across those months, leaving some doubt about whether PCE growth will make a positive contribution to the 2009:Q2 GDP numbers.

|

Consumer sentiment has lifted, but has not apparently brought spending up with it.

|

The reason for that, I believe, is that the recent consumption slowdown is not an “animal spirits” kind of move, but instead is at least in part a response to a previous profound imbalance in the ratio of household debt to GDP. Capital markets were seriously malfunctioning over 2004-2006, with many loans made that we can see today were in the interests of neither borrowers nor lenders. Deleveraging is going to be an unavoidable part of the correction process, no matter how consumers feel.

|

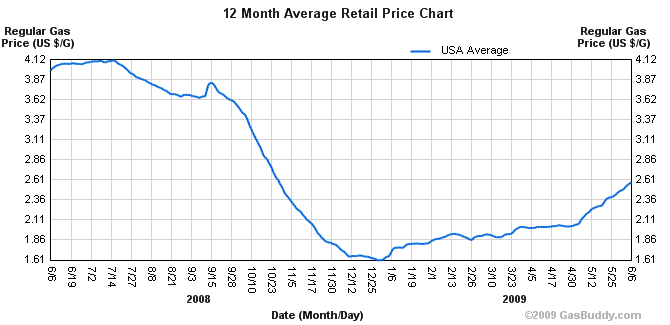

The drop in oil prices since last summer was certainly helpful for that goal of strengthening household finances. But that also makes the significant move in oil prices back up since December a troubling development.

|

The 16% increase in gasoline prices between December and February resulted in an additional $37 billion spending by consumers at an annual rate on gasoline and fuel oil, increasing the share of energy purchases in consumer budgets from 4.85% in December to 5.17% in February. The additional 40% increase we’ve seen in the retail price of gasoline since February has likely brought that expenditure share back up above 6%.

|

A robust recovery? How and where?

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

autos,

auto sales,

economics,

recession

“One indicator I’m watching in particular is new car sales, since current sales are unsustainably low …”

Although I rate most of this post as excellent, on this point I think you’re making the same

kind of mistake that was made by Bernanke and so many others when they opined that housing prices couldn’t fall nationwide, and at worst would stagnate. There’s been a phase change in the economy, and in many sectors it’s just not going to behave the same going forward.

How many times did we hear “industry experts” and famous economists confidently declare that “the demographics” guaranteed housing demand would keep pace with, even outpace, production — that there was no possibility the pace of sales would fall. But they were completely wrong; the bubble caused the number of people per household to decline as it artificially inflated demand, especially by pulling demand forward among the younger age cohorts. Now that trend has reversed as people who bought homes they couldn’t afford end up having to move in with friends and relatives. It’s manifestly clear that the US population can be adequately housed in a much smaller number of housing units than we have today.

I’ll wager that we’ll see going forward that the US population can also be adequately transported in far fewer vehicles than we have today, even when employment starts to recover, but especially over the next few years as ever-fewer people even have jobs to go to.

Moreover, improvements in vehicle quality, especially in rust resistance, have been such that if people decide to start keeping cars longer they’ll be able to keep them for a very long time.

maybe u missed an important indicator:

the orders-to-inventories ratio. It jumped lately…at least a little kind of hope from this fact. In any case, domestically…the US economy is far from “robust”.

Very good summation. The recent jump in mortgage rates may have a similar effect to the housing market as the jump in gas prices to consumer spending.

There was a big jump in Treasury yields in 1931 when the Fed had a diametrically opposite policy–they raised rates to minimize gold outflows. Now the Fed seems to be in a bind. If they buy bonds to lower rates, they increase chances of inflation later and the risks of owning long-term bonds. The law of unintended consequences would seem to make it unlikely the Fed can thread the needle with the perfect policy for a painless recovery.

Morely’s paper, like so much written comparing this to previous post-war recessions, seems to minimize the fact that this recession is really of a completely different nature than all the others. For instance, if they are going to use 1974 recession as comparison (as many have), they should explain why the very different nature of the event isn’t relevant. At that time both household and business debt were much smaller, and assets of both increased in value during the recession.

I think most of the recession numbers after Lehman is a fad- a fashion- information exchange phenomena- current fad is “we can not trust the banks” and fads have a property to disappear almost as fast as they start, with en exponential tail- since they are immaterial, in a sense-have no inertia.

So I think economy will return to pre Lehman levels sharply, as fad of recession disappears.That us what intial claims graphs suggest every time- firing people is a fad. From there on, it will slowly work out the fundamentals.

edo the orders-to-inventories ratio. It jumped lately..

I’m not sure about that. Apr 08 to Apr 09, inventories are down 5.6%, new orders down 23%. The inventory/shipment ratio, the one commonly used, has been stuck around 1.45 since January.

http://www.census.gov/indicator/www/m3/prel/pdf/s-i-o.pdf

I would agree with jm about autos. When I was in high school, the kids who had cars had complete clunkers. Go by a school parking lot now and you won’t be able to tell the students’ cars from those of the faculty. And in the semi-rural area where I live, many couples have a third vehicle, a p/u truck, motorcycle, etc. I think there is an awful lot of slack there.

One thing that will cause another recession in the next 5-7 years is the currency appreciation of China.

This will make oil prices surge (due to Chinese purchasing power of oil rising, as the CY buys more dollars). At the same time, US trade deficit with China will improve and even vanish.

But it will take a recession to sort all that out.

Car purchasing may be unsustainably low under traditional assuptions, but what if one takes into account that :

1) Some people might just permanently choose to carpool more, given that gasoline will permanently be above $3 over the medium term.

2) People who might have bought $50,000 cars may just buy $25,000 cars, particularly since the biggest difference between the two price tiers is electronics, which plunges in cost over just a few years anyway.

In terms of electronics :

2009 BMW 5 > 2009 Honda Accord > 2001 BMW 5 > 2001 Honda Accord.

3) Low cost cars like the Tata Nano will sell in the US by 2012. They won’t displace much of the US market, but it could easily eat up 5% of the market, dragging down the ASP of cars sold.

I would like to see the charts on GDP with, and without MEW (Mortgage Equity Withdrawl) this alone is proof of SGM (Slow Growth Mode) for years to come. Most of those big ticket items were paid with home equity withdrawls not wages, or savings.

We are at the beginning of a huge change in resource utilization. There’s is over capacity everywhere.

It will take a decade, at minimum, to effect the changes necessary.

The key is not statistical analysis but political intrusion. The elephants in the room are still cap-and-trade and nationalized health care.

The Obama Economic team, through the leadership of Christina Roomer – who has become perhaps the most dangerous person in government – has given us an analysis of health care rationing under the Obama administration. Betsy McCaughey states it correctly in her Wall Street Journal article: “Telling all Americans they have to cut back on health care because Medicare is fiscally unsound is like ordering all Americans to go on diets because the food stamp program is in trouble.”

Note that “risk profiles,” mentioned below, are used in most nationalized health care systems with gruesome results for the elderly. For example both the Canadian and British health care systems refuse certain care for the elderly at any cost unless the patient moves outside the nationalized system, in Canada that means out of the country. It appears that our government is setting the stage to save nationalized health care by euthanizing the Baby Boom Generation.

Most of the paper is an analysis of how much the government will save through the reduction in health care services through the Obama administration’s nationalized health care proposal, but most telling is the comment that the analysts do not even know if the reductions in health care services would actually give them the savings they spend pages and pages projecting.

THE ECONOMIC CASE FOR HEALTH CARE REFORM

JUNE 2009

EMBARGOED UNTIL TUESDAY, JUNE 2

THE ECONOMIC CASE FOR HEALTH CARE REFORM

Excerpts:

A DIRECT CALL FOR RATIONING

P. 18 – Systems should reward providers who deliver care that adheres to evidence-based guidelines and should not pay for preventable medical errors. Examples may include bundling payments for certain types of outpatient care or procedures, using blended payments when there are multiple treatments that are mutually effective, and denying payments for certain health care associated infections and never events. Given the extensive variation in utilization and spending, other reforms might include directly targeting individual providers or geographic regions that are high-end outliers.

TAKING HEALTH CARE DECISION OUT OF THE HANDS OF PATIENTS

P. 19 – For many types of medical conditions, a patient may have a choice of several methods or treatments, each having different benefits or risks. Systematic examinations of the merits of different treatments and dissemination of the results of those examinations to patients and providers is one mechanism for promoting high-value care. Health information technology may play an important role in increasing the rate at which new information broadly diffuses to providers and is incorporated into practice behavior.

LIMITS ON HEALTH CARE CHOICE THROUGH GOVERNMENT RISK PROFILES

P. 19 – Additionally, new efforts could be made to generate risk-adjusted provider performance profiles to encourage quality improvement and to inform consumer decision-making around quality.

REDUCED HELATH CARE CHOICE THROUGH ONE-SIZE-FITS-ALL BUNDLING OF HEALTH CARE

P 19 – Some have advocated strategies that promote reduced fragmentation and greater coordination through the use of financial incentives such as bundled payments for specific episodes of care. Another type of fragmentation is administrative. The unique systems of payers lead to greater administrative costs for hospitals and physicians. One proposed strategy would be to create a standardized electronic billing, benefit determination, preauthorization, and patient payment determination method that could be used by all providers and payers and lead to administrative simplification.

FINANCIAL INCENTIVES MEANS FINANCIAL PENALTY FOR LIVESTYLE CHOICES

PP. 19-20 – Engaging patients in medical decision-making can lead both to better alignment of treatment strategies with patient preferences and to lower costs: well informed patients are more likely to be comfortable with less invasive, extensive, and expensive treatment options. Another strategy involves creating financial incentives for patients needing complex surgeries to use high quality, lower total cost centers of excellence. It will also be important to encourage individuals through education and incentives to make healthier lifestyle choices, such as exercising and healthy eating.

CHANGING THE FOCUS OF RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FROM CARING FOR ILLNESS TO COST REDUCTION

P. 20 – Rewarding high-value technology creation that reduces morbidity, mortality, and total spending over the lifetime.

REMOVING HEALTH CARE CHOICE THROUGH BUNDLING CARE INTO AN EXCHANGE

P. 20 – An exchange could perform several functions, including coordinating health plan participation; negotiating premiums with insurers; creating and disseminating consumer information about benefit designs, premiums, and plan quality; facilitating enrollment; and coordinating risk adjustment to reduce insurers risk in the event of adverse selection within the exchange. By adopting an exchange, it is possible to reduce the cost to individuals and small employers that is associated with shopping for coverage and to generate greater efficiencies in the marketing.

THE AUTHORS ADMIT THEY DO NOT KNOW IF THIS RATIONING WILL ACTUALLY WORK.

P. 21 – Though we describe them separately, it is important to note that there may be interactions between expanding access to coverage and slowing cost growth. Thus, the distinction between cost growth containment and coverage expansion may be a somewhat arbitrary one.

THE GOAL IS REDUCED COST TO GOVERNMENT BY REDUCED CARE TO PATIENTS

P. 24 – In this analysis, we assume that all of the savings to the Federal government take the form of deficit reduction

Beezer..it will take a decade…..

I concurn completely. The entire world economy is changing and we only at the beginning of the cycle. It does not mean we will not do well, it means we will do well with less!

Prof. Hamilton,

I would echo some of the comments regarding vehicle sales. This topic comes up from time to time on Calculated Risk and he holds essentially the same opinion as you. While the sales rate is low, if you look at something like the ratio of vehicles per licensed driver and how that has changed over the years there might be more to consider. E.g. 3 car family becoming 2 car, current vehicles to driver is >1, etc.

The data can be found in the following links:

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/ohim/hs06/index.htm

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics/2007/

http://www.bts.gov/publications/transportation_statistics_annual_report/

http://www.bts.gov/publications/national_transportation_statistics/html/table_01_11.html

I started to do a bit of analysis but never got as far into it as I would have liked.

I have been in the health care industry for ten years. Part of the overhead (like so much of health care today), unfortunately, but part of it nonetheless. I am also an early babyboomer. In addition,I am also a primary care giver for my mom who is in a nursing home here in the Twin Cities. I have have been watching her consume in excess of $1000/mo in pills (Medicare), $3500/mo in benefits (Medicaid, in additon to her SS check)along with frequent treatments for pneumonia and problems associated with her stroke (more Medicare). Oddly, she’s in better shape than many of the folks here – you ever notice how many geezeers walk around with oxygen tanks? In any event, this is just one nursing home in one state. I love my mom and glad she’s doing okay but it doesn’t take an astrophysicist (or an economist) to figure out that this is not sustainable.

It sounds great that everybody’s mom and dad can have the greatest care in the world including hip replacements, heart bypass and dialysis but it is simply not sustainable at least the way it’s going. The country cannot afford this even now and definitely cannot afford it for us babyboomers.

I happen to believe that healthcare is a right and not a luxury but it doesn’t really matter. One way or the other some sort of rationing is going to happen even if we can figure out how to get rid of the huge amount of overhead like me that’s in the system now.

Fine overview, Professor.

I share your skepticism.

Fascinating analysis of the analogs between the ’29-’33 Great Depression and today:

http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/3421

We are in the early stages of a depression, and the accelerator is about to be floored, if states and cities implement the cuts — e.g., stopping CalWORKS — that they have been threatening:

http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/lanow/2009/05/schwarzenegger-make-massive-cuts-to-welfare-health-care-student-aid-.html

It is going to be a very interesting summer and fall here in California and the U.S.

@ Mr. S:

“I happen to believe that healthcare is a right and not a luxury…”

I hear this argument often, usually pertaining to issues like education and health care. It seems that for some, emotional appeals to the supposed inviolable nature of universal accessibility to goods like health or eduction trump logical appeals to the sheer impractibility of the universal allocation their advocates demand. But scarcity – and the economic principles it imposes – is universal. Regardless of whether something is considered a “right” or a “luxury,” economic laws govern its allocation. To the extent that this something – be it healthcare, education, or something altogether different – is a right, economic analysis becomes more, not less, important. Such analysis is uniquely qualified to ensure that goods are distributed to as many as possible, with the highest level of quality possible.

In short, if you’re of the opinion that some good (in this case, healthcare) is a right, you should also be willing to embrace any mechanism by which it can be delivered to largest amount of people without compromising some baseline measure of quality.

Footwedge wrote:

I happen to believe that healthcare is a right and not a luxury but it doesn’t really matter. One way or the other some sort of rationing is going to happen…

It absolutely amazes me how logic simply no longer exists in debate and words just mean what ever the speaker wants them to mean, which means nothing at all.

If something is a right logically how can it be rationed? Are rights really rationed? Are we to ration the right to free speech?

It is amazing how poor education is today and it is amazing how intelligent people can be so illogical. But then again I guess if illogical thought wasn’t the case we wouldn’t have central planning.

“A robust recovery? How and where?”

At the risk of having a 1929 Irving Fisher moment, let me play the devil’s advocate and take a “big picture” approach to answering these questions with some optimism. Specifically, despite the serious challenges presented by household deleveraging, I think there are good economic reasons to think that a robust recovery is, at the very least, possible.

Consider the production side of GDP. Like Professor Hamilton, I believe that recessions can correspond to permanently lower potential (aka Ybar). However, I’m pretty sure that output has fallen further than potential in at least the past two quarters (i.e., Y-Ybar is negative). Thus, the re-employment of productive labour and capital could lead to a high growth recovery. For labour, productivity has been growing throughout the recession, meaning that an increase in hours and/or a decrease in unemployment could produce a lot more output. Also, capacity utilization is at historically low rates and a reversal would allow output to grow at a fast rate.

On the other hand, I believe that Professor Hamilton’s concerns about a robust recovery relate more to the expenditure side of GDP than the production side. So, even if potential output is higher than current output, there is a reasonable question of why firms would choose to re-employ labour and capital in H2 of 2009.

To address this, let’s start with the expenditure identity: Y=C+I+G+NX.

First, “G” is clearly going to contribute to growth in the near term as the stimulus spend-outs start to come on-line.

Second, “I” could increase rapidly if firms choose to restock some of their inventories. Even though I suspect that the historical relationship between inventories and output has changed somewhat since the mid-1980s, a large and quick restocking of inventories is still quite possible and would produce above-average growth in the near term. Also, some firms may be attracted by low costs of capital to make large investment expenditures. As an example, I noted a WSJ article last week about United Airlines contemplating a major purchase to update its fleet. While they are waiting to see what deal Boeing or Airbus offers, the example illustrates the potential for a large upswing in “I” once forward-looking firms see light at the end of the recessionary tunnel.

Third, “NX” could be helped out by a weak dollar and a recovery of the world economy (aka Y*). While Europe remains a question mark in my mind, the BRIC countries, Canada, Australia, and now Japan (see latest IP) all appear to have reasonable economic prospects in the near term (i.e., Y* may be a positive contributor to growth, rather than a drag).

Last, but alas not least, we come to “C”, which is the source of our greatest worries given its large share of total expenditures and the compelling stories for its ongoing weakness. I doubt that a recovery will be led by the household sector, but I’m not convinced that things will necessarily get worse. Drags on consumption due to poor consumer credit market conditions and a large wallop to household wealth have eased somewhat in recent months. To be sure, they are still drags (housing wealth certainly hasn’t recovered yet). But given that household balance sheets have stopped deteriorating, consumers may be done adjusting their savings rate. They may keep it at a higher level for the foreseeable future. But keeping the savings rate constant has very different (i.e., less negative) implications for near-term growth than increasing it further.

Before everyone in the econ blogosphere starts yelling at me for being too Pollyanna-ish, let me reiterate that I recognize there are serious downside risks to the US economy and I am mostly addressing whether a robust recovery is possible, not whether it will 100%-absolutely-for-certain happen. Also, I am deliberately trying to avoid the group-think and risk aversion that characterizes much of the econ blogosphere at this moment (although Professor Hamilton stands out as an exceptionally independent and clear-headed thinker in this realm, so I pay particular attention to his concerns about the recovery). My simple point is that a robust recovery (in the form of a few quarters of well-above 3% annualized real GDP growth after the trough of the recession) cannot be completely ruled out.

Kris, the very fact that healthcare, as a universal right to all citizens, suffers from supposed “impractibility” is why the government should provide it and not for-profit companies. Take it out of the equation for buisnesses to decide if they should provide healthcare to someone who needs it but may not be able to afford it. If you’re sick, you go to the hospital and get better. No questions asked. Surely this is a utopian-type aspiration and, as you concluded, I will surely embrace any mechanism that strives to deliver that aspiration, with the goal that such a mechanism can and will improve as often as possible to get ever closer to universality.

Maybe we shouldn’t invest in so many guns?

“If something is a right logically how can it be rationed? Are rights really rationed? Are we to ration the right to free speech?”

Rights are rationed all the time. Free speech is rationed. The government can put limits on the “time, place, and manner” of free speech and ban certain types of speech altogether such inciting people to riot. Everyone can’t go on TV for fifteen minutes each day, that is rationed and not just by the marketplace. But free speech is still a right.

There is a distinction between basic care and something like hip replacements for the elderly. A health care system can determine that the young have better claim on health care than the elderly, or vice versa.

Ryan and Ed, your posts are a joke, right? Just reacting to DickF’s observation that smart people can be illogical, right? Right?!?

@Kris – I wasn’t the one making the comment regarding the healthcare being a right. Mine was the comment with the links on vehicle ownership per licensed driver in the US and wondering if the near future might hold a return to 1 car per driver.

Why do we focus on new claims, or new jobs added for that matter, in absolutes over time. Population and productivity are not fixed. The flow as a percentage of workers would be more informative, no?

kris says :

>It absolutely amazes .me how logic simply no longer exists in debate and words just mean what ever the speaker wants them to mean, which means nothing at all. .. If something is a right logically how can it be rationed? Are rights really rationed?

Hmm.

I’m here with 3 other people in a life boat in the middle of the Atlantic.

We have one bottle of water between us.

We may be here some time.

We all could be said to have a ‘right’ to water.

Does that mean I have the ‘right’to drink the whole bottle because I’m very thirsty ?

Let’s say I DO drink the whole bottle.

The other people presumably still have the ‘right’ to water.

Trouble is, unfortunately as of now, there’s no water to have any rights to.

Same with medicine.

If it would bankrupt the country to give everyone the best possible medical care, then everybody just isn’t going to get the best possible medical care, no matter how much they may shout about their ‘right’ to it.

People here in London during the Blitz presumably had the ‘right’ to life.

Didn’t stop large numbers of them being blown to smithereens by the Luftwaffe.

Seems to me a ‘right’ is an expression of an ideal state of affairs which may or may not be attainable in practice.

I have followed this blog for some time and I respect (and agree with) most of Dick F’s comments and do not wish to be on the wrong end of them. Nonetheless, I will stand by my assertion that access to healthcare should be a right, at least at some level. (Perhaps the basic care that Ed mentions?) I understand the conceptual difficulty of thinking of them as a right especially, as Dick alludes to, other REAL rights, which I assume are only those spelled out in the constitution. I also have no misconception about the difficulty of even attempting to treat it as a right. Even though every country in the developed world (except us and South Africa) has some kind of single payer system none of them are apparently very good or, God help us, efficient, economically or otherwise.

And I am in total agreement – often with Dick – that Americans consider far too many things a right.

Yet the facts are indisputable: among them, our health care is by far the most expensive, we rank 41st in longevity and we have 45 million fellow citizens that have no health care at all (obviously a Darwinian rationing of some sort). Rationally, any system that tells someone that doesn’t have money for insurance or treatment that they should just suffer or die (or go to the ER so the GOVERNMENT will end up paying anyway) is not only immoral it is economically stupid. It also occurs to me that if this is the best that an alleged free market system can do then perhaps, as with a lot of our other “institutions”, some re-thinking of this is in order as well.

But then I look at our banking system and Chrysler and GM and shudder – maybe Dick is right after all. . .

First there are not 45 million people without healthcare. They show up at the emergency room, and that is part of the high cost paid by the rest of us. The reason they show up at the emergency room varies from true destitution to, in the case of several I know who can afford the 40.00 fee at the after hours clinic, to the understanding that the hospital HAS to treat them, not matter how often they don’t pay. These folks are cheaters, plain and simple. Many people could pay, but they prefer to spend their money on beer, or Six Flags tickets. Because it is the law, most of these people manage to have car insurance. We need to remove health care from anything to do with employment, which is a stupid but convienient money source for the government mandate, and simply make it the law that individuals carry some universal minimum liability health care, with the cost based like car insurance, on your use or abuse of it. Subsidise a payment to the really indigent, and most of the problem is taken away. If we took paying for eyeglasses, and oil changes (routine medical visits) out of insurance, and put it back into the consumers pocketbook where it belongs, there would be billions available for true catastrophic care for virtually everyone. We have distorted the marketplace by making people think they are entitled to routine medical care paid for by someone else. People want freebies, remember the outcry and quick repeal of the catastrophic coverage bill back in the 80’s. Think of it as a food stamp program, just as no one starves in the US, if you want steak you may have to pay more and work harder, and take better care of yourself, by not smoking, or getting thin. While I agree it is unfair from the point of view of feckless foolish irresponsible leeches, that Bill Gates can afford the Rolls Royce health care vehicle, and lazy good for nothings can only get by for free in the emergency room clown car, short of making Bill Gates go to charity hospitals, and Prestigious Doctors who worked hard to get a Six figure paycheck work for the same wage as a couch potato there is no way to bring “fairness” which is really what we’re talking about here, not rights, to the system. There is no “right” to anything, if it is given by your fellow man out of his pocketbook, and it ought to be appreciated, and not treated as if it weren’t enough. I have never never heard a thank you for anything from the food stamp user, and there won’t be one from the health care sucubi either.

As a last thought if you think somehow our multi-tier system is going to be made into a “fair” single tier system, you’re an idiot. There will be a 2 tier system, a nasty miserable British style level for us proles, and of course the much better level for the truly important. All the bleeding hearts are going to accomplish is ruining the middle level that is keeping footwedges mom in some comfort that thanks to her irrational guilt footwedge won’t have when her time comes. The world is grotesquely unfair, and making EVERYONE more miserable doen’t make a kid dying at 5 from cancer feel any better at all. Research, free markets, personal incentive, and drive have made huge advances in the mitigation of human suffering. Bill Gates and his software, have given us 3-D sonograms people are putting in baby books, MRI, and CT scans that show in exquisite detail the inner workings of the human body. What have most of the great unwashed contributed to these miracles, or the wellfare of even themselves, let alone others, that I should worry about them beyond making sure they’re fed, and don’t die in the street.

Rationing done by the government, or rationing by personal choice of lifestyle which would you rather have? We have fundraisers here for worthy folks who have excessive medical bills, but it is a small town, and so we also don’t have fundraisers for folks who got drunk and drove into trees, or beat their children, and now need heart transplants.

It occurs to me that people need food to live, too, certainly as much as or more than they need medical care. And certainly, there are as many or more people without guaranteed provision of food than there are of medical care, given the existence of hospital emergency rooms.

So why, I wonder, is it that we aren’t having to deal with a crisis of the effect of the rising cost of food in potentially bankrupting the government’s entitlement systems? Why is it that we aren’t having to figure out how to provide government subsidized food to everyone?

What is it in this country about the provision of one vital good — medical care — in contrast to another — food — that causes one to be a problem, but not the other?

Hmm.

Perhaps some supposedly bright people need to step back and rethink the source of the problem. Could it be related in some way to a lack of competitive markets in one versus the other? If so, wouldn’t the solution be to guide the provision of medical care toward that of food?

Given what we know after decades of failed experimentation with central planning in dozens of countries, do you people really think you or anyone else is smart enough to “solve” this problem by controlling the provision of such a vital good — any vital good, medical or otherwise?

I’m well enought off and can go wherever I want to get what I need — I’m not bound to any country. You’re not going to effect me or people like me with your hubris, at least not in my lifetime. All you’re going to end up doing is to drive this thing into the ground, and hard. And the people it’s going to hurt most are the people you’re claiming you most want to help.

Government planning has never worked, and it never will work. You’re just not smart enough to see that.

The biggest risk is uncontrollable rising US bong yield. The rising US bond yield comes from the rising budget deficit and the rising US government debt problem in the long run. Some may think the rising bond is the normal situation due to the improving economic outlook; however, the main reason is the government budget deficit and rising government debt. Another main catalyst (not major reason) is the quantitative easing program that creates the increasing inflation expectation and liquidity. We could see the inflation data and UofMichigan report this month show the jump in inflation and inflation expectation; and these events could push the 10 year bond yield up to 4.5% by the end of this month and US do not stop the large budget deficit, rising debt and QE program we could see US 10 year yield at 8-10% by end of this year.

Some may think rising bond yield is good sign for the higher growth but the growth could falter from rising cost of borrowing. The biggest concern is the rising bond yield could persist to attract money to move back to invest in US dollar and cause the rising US dollar. This could be the best trade for this year: Short bond yield and long US dollar.

If the rising US bond yield and rising US dollar value occur together, it will cause the tale of two worst: the bond and stock are worst.

Some may think this could be the deflation in the future and at some point bond yield should move down; however, the bond yield is totally expected by the behavior of US government on the budget policy and the inflation expectation by FEDs QE. If we have the declining economy, we know the government and FED will use larger budget deficit and more QE and it will cause the higher bond yield.

Now we are facing unusual environment. The equities should drop sharply from here from the false expectation on growth from ring bond yield because it comes from the fiscal and monetary policies not from the growth expectation.

I am not sure if the bond yield and US dollar are moving higher and how the economy looks like? It should be the depression with the volatile expectation on price and growth. I still believe the only long term policy can tackle this problem. The government must ensure the long term government debt by spending from taxing the rich and FED must ensure the low inflation and inflation expectation.

Footwedge,

I appreciate your kind words.

Health care is not a right. Health care is a good and/or service. The confusion is a creation of politicians to rhetorically increase the strength of their logically weak arguments.

Is there a right to food? Is their a right to a car? Is there a right to tickets to the Lakers/Magic basketball games? This whole line of argument is foolish and takes us down a road of irrationality.

Rationing can only apply to goods and services, a scarce commodity. A right is not a scarce commodity, but a universal truth. For this reasons your assumption, “…other REAL rights, which I assume are only those spelled out in the constitution…” is not correct. Madison did not want a bill of rights just because of this. He did not want to enumerate rights because he knew politicians would then use the document to supress rights enumerated.

The whole argument has been intentionally shifted to say that only government can protect rights and so since health care is a right only government can solve the problems. But if you understand that health care is a good then you understand that government will destroy supply. Only the market can provide more and better service at a lower price. Government will ration health care at a higher price.

Just look at how health care costs have boomed when the government began to pay for services through social security and medicare. This is what makes Betsy McCaughey’s statement in the Wall Street Journal article: “Telling all Americans they have to cut back on health care because Medicare is fiscally unsound is like ordering all Americans to go on diets because the food stamp program is in trouble,” so profound.

-@ Mr. S:

Sorry, I’m new to the Econbrowser comments section and got confused on comment attribution.

-Ryan said: “Kris, the very fact that healthcare, as a universal right to all citizens, suffers from supposed “impractibility” is why the government should provide it and not for-profit companies.”

Ryan, with all due respect, you’re engaging in stage one thinking by treating the symptoms instead of the disease. WHY has it become increasingly impractical and unwieldy for the private provision of health care? WHY has it become increasingly unprofitable to provide healthcare?

Advocating government provision of healthcare because it’s increasingly unprofitable is like advocating for increasing the minimum wage because wages are stagnating.

-@jamtommorrow: I didn’t write that comment. You have attributed to me something I didn’t say.

Please don’t conflate my defense of privately provided healthcare with a defense of the status quo. I, like most here, recognize that there are huge problems with the current state of healthcare in this country and would like to see it radically changed. But I’m of the opinion that we’re moving in the opposite direction of where we should be headed, that universal healthcare will compound (rather than solve) the problems of healthcare.

I for one welcome the rising bong yield.

Is it a coincidence that the bong yield was written about by a “young economist”?

😉

We need a little levity on this blog.

What do you think of this compromise (hat tip to Arnold Kling):

Get rid of all private health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid. Go to a single payer, government provided system, mandatory for all.

Premiums would be paid for with after tax dollars. It would be a high deductible plan, catastrophic insurance. Routine care would be paid for 100% out of pocket. Even after hitting your deductible, you would be responsible for the cost of, say, 50% of your care.

This, of course, would cause a revolution in this country, especially amongst the elderly, who have come to expect to pay nothing for health care. And paying so much out of pocket would be a revelation to most people. Doctors would hate it.

But does anyone doubt that it would completely eliminate health care inflation? And is there any doubt that actual health would be no worse?

Ouch! Painful but thoughtfully excellent rebuttals to my contention that healthcare is a “right”. It is apparent, however, that I neither thought through nor expressed my supposed solution very well. Kris really expressed it much better; we have huge problems that need to be addressed but the government should not be the solution. I am am concerned, though, that we spend so much time worrying about the latter that we forget about the former.

I will reluctantly back away from my statement that health care is a right but I suggest that it is fundementally not just another conusmer product that is easily managed by the laws of economics either. I work for one of the largest health care companies in the US. Like others, we have been offering so called “consumer driven” products for several years. These are exactly the way we need to go because clearly people need to have skin in the game in order to make smarter decisions about their health. Nonetheless, we have noted in our data that the actual decision of when to use health care and who to see is still not driven by economics but by emotion – it is the rare patient that wants to see a doctor who finished last (cheapest) in his/her class and clearly someone did. We all want the best (and most expensive) provider when it comes to our health and why wouldn’t we? My point here is not to say that we shouldn’t have choices but simply that unlike most choices in the marketplace, decisons about health are not purely supply/ demand, most efficient, least expensive. Aside from the enormous overhead in our business, this is another large part drivng the costs of healthcare in this country and why it takes 15% of our GDP to support it. (Not to mention malpractice insurance and all the baggage that goes with that.) I don’t wish to be pummeled again for suggesting a solution and I don’t have one anyway but I will be foolish enough to say again that what we are doing is not working and is killing us financially and literally. We need to address this now and not later.

Footwedge wrote:

My point here is not to say that we shouldn’t have choices but simply that unlike most choices in the marketplace, decisons about health are not purely supply/ demand, most efficient, least expensive.

Footwedge,

This is not an attack on you but I would like to use your comment as a spring board. There is a serious distortion of what free market economics is all about from those who wish to expand central planning. They imply that economics is all about cost or efficiency and they say that is wrong. Then they support central planning by appealing to arguments of cost and efficiency.

The free market is about free exchange not cost and efficiency. The free market is not about making one product as efficiently and inexpensive as possible, that is the central planning approach.

The free market is about allowing you to choose to allocate your own resources as you want. If you choose to be inefficient then so be it just as long as you and your trading partner both consider yourselves better off.

I may consider baked potato chips more efficient and satisfying than sour cream potato ships. Shouldn’t I have the right to choose? But shouldn’t you have just as much right to choose sour cream? But the government would say that we are more efficient if we only manufacture one type of potato chip. The miracle of the free market is not so much its effeciency but the fact that it will satisfy the wants and needs of even minority consumers.

The bottom line is that government is awful at satisfying wants and needs, but is very good at enforcement. We should not attempt to force government do what it cannot do.

This is a great post that touched on a lot of issues. I enjoyed the note from James Morley. In his comment above, he says:

“But given that household balance sheets have stopped deteriorating, consumers may be done adjusting their savings rate. They may keep it at a higher level for the foreseeable future. But keeping the savings rate constant has very different (i.e., less negative) implications for near-term growth than increasing it further. ”

-If consumer keep their savings rate steady going forward, wouldn’t that suggest lower consumption growth and lower GDP growth relative to the last 15 years, in which the savings rate was declining. So perhaps the new potential growth is 2% and not 3%… something like the “L” you describe in your paper?

“My simple point is that a robust recovery (in the form of a few quarters of well-above 3% annualized real GDP growth after the trough of the recession) cannot be completely ruled out.”

-Certainly the stock market seems to have priced in a quick recovery.

Kris,

Until for-profit companies aren’t the conduit between health and citizens, there won’t be a change in the status quo. Trying to dress up the current health care system and call it something else won’t change anything. We need radical change and that means socialized medicine. And that’s not a four-letter word in my opinion. We have socialized education, mail delivery, police protection, fire protection, military protection, border protection, transportation… why not socialized medicine?

Good post, Jim.

One of the few fully honest presentations on where we are that I have read.

In regard to the healthcare debate. Most doctors would welcome universal catastrophic coverage and not having to hire one fulltime biller per physician. Also the fact the medical bills are a major contributor to personal bankruptcies should moot the point of continuing the current system.

@ Footwedge:

1.) I wasn’t trying to say that healthcare isn’t a right; just that whether one considers it a right or a privilege doesn’t resolve fundamental issues like scarcity.

2.) I think this is the first time in internet history that someone has conceeded a point. Kudos for being open-minded. The internet needs more like you.

@ Ryan:

Ryan said: “…We have socialized education, mail delivery, police protection, fire protection, military protection, border protection, transportation… why not socialized medicine?”

I mean…really? That you consider the relative condition of those industries to be convincing evidence of the efficacy of government solutions to economic problems is rather instructive.

Your lack of a rebuttal is “rather instructive” as well, Kris. If you’re trying to imply that those government services are lacking and therefore creating a government service for the health industry whose current “relative condition” is arguably worse than the services I mentioned (I quite appreciate being able to mail packages for less than two bits, as do I appreciate that, you know, guys with guns out there keep me safe), than I wholeheartedly disagree.

I mean… really? (sorry, no point concession here. I don’t like Kudos anyway)

There exists one robust link between the rate of real GDP growth and S&P 500 return, Rp(t) (12- month cumulative return). The predicted returns can be obtained from GDP using the following relationship

Rp(t) = 15.0*dln(GDPpc(t)) – 0.32

where GDPpc(t)) is represented by the mean (annualized) growth rate during four previous quarters. Both series are contemporary. This relationship accurately predicts S&P 500 during the past 20 years.

When reversed, it predicts GDP from S&P 500. Because S&P 500 has increased from 735 (close) in February to 919 in May, one can expect a rise in real GDP of +5% or even more. This is the start of recovery as S&P 500 indicates.

http://mechonomic.blogspot.com/2009/06/mechanical-model-of-pid-introduction.html

Health care is a right for those that have earned it. For those that can’t pay for it, they have a right to force us to earn it for them.

Right?