In which I join the ongoing debate on how much we should expect fiscal and monetary stimulus to accomplish.

Arnold Kling has proposed a “recalculation” theory of macroeconomics:

My claim (which is not original with me– it is recognizably Austrian) is that a recession can be thought of as a recalculation. Imagine a central planner who decides to radically change plans. He has a huge recalculation to make in order to figure out where to allocate labor and capital. He says to some people, “Wait a minute. I am thinking. Some of you just have to stand idle while I figure this out.”

The market economy is like that central planner. We are undergoing a Great Recalculation….

In conventional, hydraulic macro, we think in terms of this one good called GDP, and the output gap is the difference between how much of this GDP stuff we could produce if everybody were working and how much we are actually producing with all the unemployment over and above “normal.” We assume that “normal” unemployment, which is structural and frictional, is some roughly constant fraction of the labor force.

The way I look at things, we have a huge amount of structural and frictional unemployment these days. There is very little cyclical unemployment–limited to autos and household durable goods. If you measure the output gap using my definition of cyclical unemployment, then the output gap is tiny.

Paul Krugman finds this unconvincing:

the whole notion falls apart when you ask why, say, a housing boom– which requires shifting resources into housing– doesn’t produce the same kind of unemployment as a housing bust that shifts resources out of housing.

It is not clear whether Paul is intending his observation as a refutation of all models that attribute a fall in potential output to sectoral imbalances, though Tyler Cowen seems to read his statement that way. To their discussion I’d like to add a paper I published in 1988. There I presented a model in which unemployment arises from a drop in the demand for the output of a particular sector. The unemployed workers could consider trying to retrain or relocate, or might instead decide to wait it out in hopes that the demand for their specialized skills will come back.

If instead of a drop in the demand for sector A there was a boom in the demand for sector B, it is true that some workers in sector A might choose to retrain or relocate, and be temporarily unemployed as a result. But the key kind of unemployment that I think this sort of model describes– waiting for an opening in the particular area in which you’ve specialized– is caused by drops in demand, not increases.

Insofar as the frictions in that model are of a physical, technological nature, increasing the money supply would simply cause inflation and not do anything to get people back to work. I should emphasize that I built that monetary neutrality into the model not because I think it is the best description of reality, but in order to illustrate more clearly that there is a type of cyclical unemployment that stimulating nominal aggregate nominal demand is useless for preventing.

My personal view is that real-world unemployment arises from the interaction of sectoral imbalances with frictions in the wage and price structure of the sort documented by Truman Bewley and Alan Blinder. The key empirical test, in my opinion, is at what point inflationary pressures begin to pick up. If Krugman is correct, we could have much bigger monetary and fiscal stimulus without seeing any increase in inflation. If the sectoral imbalances story is correct, it would be possible for inflation to accelerate even while unemployment remains quite high.

I would also emphasize that even with a sectoral-imbalance interpretation, there is a clear potential for fiscal policy to have made a positive contribution by preventing job losses caused by state and local government spending cuts. Under the “hydraulic macro” view, as long as the federal government increases spending by the same amount that state and local governments decrease spending, we’d be OK. Under the “sectoral imbalances” view, a $1 increase in federal spending combined with a $1 decrease in state spending is on balance contractionary, and that downturn would have been preventable by a simple fiscal transfer from the federal to the state level. I note that

one-fifth of the seasonally adjusted job losses in September came from a decrease of 47,000 in the number of state and local government employees. I am still persuaded that the nation would have been better served with the stimulus bill I proposed in January in place of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Whatever your position on that, I’m presuming we could all agree that things have not developed so far in the way that we would have hoped.

|

You can find more discussion from Arnold Kling ([1],

[2]),

Ryan Avent,

Robert Waldmann, and

Matthew Yglesias.

I think Krugman’s problem is that he seems unaware of the importance debt is playing. The reason we didn’t experience a rise in unemployment as investment was shifted from the technology sector to housing/finance is that the capacity and willingness to take on debt was all but bottomless.

Now we need to rebalance from real estate and housing and both the capacity to take on debt, and the willingness to do so are in the toilet. We need to shift resources to manufacturing at a time of historic levels of global over-capacity.

Krugman is very good at the glib, facile explanation. But if you look back at his writing in 2002-2003, when, for instance, he called for a housing bubble, he looks pretty myopic. His piece in the NYT’s magazine was self-serving drivel.

It’s the deleveraging, stupid.

Bob_in_MA: Krugman … called for a housing bubble.

When did he call for a housing bubble? I recall him saying that we would probably have a housing bubble and he was right. I don’t recall him saying that he thought that this was a good idea. Perhaps you are confusing the descriptive with the prescriptive.

So, if I read your stimulus proposal correctly, you are in favor of the Federal government to effectively pay people not to work.

Or do you think the Feds giving cash to State governments would result in State based industrial policy initiatives to promote the creation of new industries and jobs on a State by State basis?

Personally, I can’t identify an “sectoral shift” In American history that hasn’t been a government promoted shift with lots of government funding. Roads and canals in the earliest years; railroads post civil war with lots of cash and land fueling that. The beginning of RFD and Parcel Post, commercial air service, big dam construction and water projects, rural electrification, repair of the land redistribution policies with the CCC. The automation of manufacturing, development of computers, et al, micro electronics, internet, aerospace, et al as part of WWII and the subsequent cold war. The massive road building to support the rise of the auto industry and trucking, shifting from rail. Promotion of health care from the first days of the nation, public hospitals, water and sewer projects, disease control and prevention, the war on cancer.

For good or ill, major growth in new sectors has occurred as a result of government policy in every case I can think of.

Some excellent points. I particularly agree that transfers to the states would have been more effective than the federal stimulus spending, though there might be some political problems in effecting the transfers efficiently.

I think that, although the structural shifts can give the unemployment a hard core, the bulk of the unemployment today is of the ordinary kind, caused by deficient overall aggregate demand. I also think that the problem is more one of the misallocation of consumption over time (people over-borrowed and over-spent because they were misled about the true value of their assets) than of a misallocation of consumption between sectors, though there was also some of the latter.

Some random comments:

Yes, we can have inflation without economic growth. See, for example, Argentina, Zimbabwe and the 1970’s US. Does the rebound in housing prices and the price of gold foreshadow inflation? I sure hope not, but if I were a pessimist…

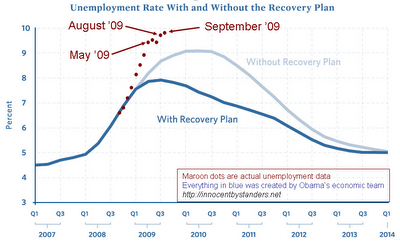

I still feel like we don’t really understand what a recession really is (and it may be more than one thing). It’s clearly related to incomes rising faster than fixed assets (it’s a variable cost-fixed cost thing, I think). But boy, what a credibility-killing graph Mankiw’s is. I mean, within months, the forecast proved to be entirely off-track. What confidence does it give us that the government understands the mechanics of the stimulus any better?

Doesn’t the last chart prove that nothing the Obama administration says should be taken seriously?

If they can be so far off in predicting the value of the stimulus package, how can we risk having them transform healthcare?

The bedrock tussle between local and federal government played a crucial role in the GD, and is likely to play a role today. The two split responsibility for transportation.

We see conflicts between state and local government on big transportation issues, Boston and its state during the GD could not get agreement about getting traffic through Boston; NYC and Albany just had a very similar fight about congestion pricing.

In 1925, downtown Boston was gridlock, and so is Manhattan today. Transportation gridlock reverses the retail demand slope, it is a sector imbalance.

Paul Krugman, 2001:

To fight this recession the Fed needs more than a snapback; it needs soaring household spending to offset moribund business investment. And to do that, as Paul McCulley of Pimco put it, Alan Greenspan needs to create a housing bubble to replace the Nasdaq bubble.

Throughout 2001, Krugman repeatedly called on the fed to lower interest rates further, with the intention of creating a housing ‘boom’ to replace the collapsed tech bubble.

I agree with Dr. Hamilton’s comments, but would like to ask which if any of those references consider the issue of how well displaced workers are able to quantitatively assess their actual prospects for various re-training options. If workers are uncertain of future demand in almost all industries they can think of (pace the daily spam I get in my inbox claiming booming opportunities for Radiology technicians), they may not be able to formulate a rational plan for re-training.

Here’s the link to the quote Dan H. provides (August 2, 2002):

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/02/opinion/dubya-s-double-dip.html

Krugman was saying the same thing he’s saying now–just do whatever it takes to ease the pain. Others warned there would be consequences, but to Krugman, they were inferiors and Cassandras.

Now, Krugman is again saying we must avoid any consequences and hat it’s impossible to throw too much money at the problem, and again ridiculing anyone who questions his logic.

I’m not a right-wing crank. I agree completely with Professor Hamilton’s prescription. Allowing the state spending to contract is absurd in this situation. But if we assume the debt-carrying capability of the next generation is unlimited, we are probably in for an unpleasant surprise.

Krugman’s credibility is somewhere near Greenspan’s. It’s time to put some of our old economic minds out to pasture. We should be trying to reason out why listening to them got us into this mess, not looking to them to give us roadmap out of this.

The last recession was clearly a sector recession, the boom being in telecom, IT, dot-coms and the related supply chain supporting these end users.

This recession is more broad based. Even tho housing is the epicenter, its tentacles reach more broadly into the financial sector(and visa versa). Also, everyone had their home acting as the 3rd wage earner in the household.

So the last recession had corporate IT investment hitting the wall, same for equity investment into dot-coms and tech in general. But still most of the country didn’t really notice we were having a recession, outside of stocks taking a hit. Then Bush started talking Iraq and Wall Street really went into a swoon.

But luckily we had a simple solution proposed by both Greenspan and Krugman (unlikely partners in agreement as that may be), which was to create the housing bubble, using the well known economic restructuring tool….low interest rates.

So unemployed computer programmers and engineers worked on losing their American and H1B Indian accents and learned a Mexican accent in order to get a construction job building houses.(I know JDH tells it different)

So far so good, but then the plan started going awry. The rest of the economy started responding and we got a massive amount of real estate agents, loan brokers, the shadow banking system securitizing loans, MEW running at $600B-$700B/year so the little people could spend on Chinese products and graduate China to economic superpower status, keep Detroit on life support building tariff protected SUVs, and the sum of these things creating huge demand driven pricing power for oil exporters. And also the tax break for the rich so they could help out and buy McMansions.

Those are a few of the highlights, and I didn’t make any of it up.

So JDH asks, “Will stimulating nominal aggregate demand solve our problems?”

I would be happy with the L shaped recovery, because who knows what could happen if they try anything else. But if forced to make a choice between monetary and fiscal stimulus, I’d say lets give fiscal target shooting a try, and rein in monetary carpet bombing.

Both the Dotcom & Housing bubbles were credit bubbles, which misallocated resources. They directed resources to produce the wrong types of goods under the influence of the artificially low interest rates manipulatively created by the central banks of the world.

For example, when you can borrow money that no one has ever saved, the US may demand 16 million cars/yr. If you get anywhere near a market interest rate, the demand would be half that. It isn’t that complicated.

Dan H.: thanks for the memory of Krugman’ previous brilliance.

I think that graph of unemployment should be corrected. That line that shows unemployment without recovery plan would be even higher than the red dots if we had taken the Hooverite action of liquidating the banks, workers, farmers and businesses.

The limit of the vertical axis would have to go to 25 – 30%.

Problem remains what poorly educated US men will do to earn a living without adequate demand for US construction labor or factory labor for the foreseeable future. How will they find a way to contribute to the economy? Federal stimulus to the banking system does not necessarily translate into US jobs. GS has asked the Fed for permission to invest its capital in Chinese manufacturers. Hard to imagine its request being denied, but that capital will not create US manufacturing jobs.

JDH,

Thanks for a clear-eyed, non-ideological examination of the subject. I hope people at the Fed are reading…they seem to put an inordinate amount of trust in their output gap thesis. Maybe they think they have no choice but to do so.

A notion cannot be made to ‘fall apart’ simply by asking a question, but rather, only by providing an adequete answer to the question posed. Krugman fails to do this.

JDH: “I am still persuaded that the nation would have been better served with the stimulus bill I proposed in January in place of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. ”

I would phrase it slightly differently.

1. Many states (Delaware, where I live, among them) have balanced budget requirements, and

2. their revenues were known at the time to be on shrinking trajectory because of the pro-cyclicality of their income taxes, and

3. their outlays were known at the time to be on an increasing trajectory because of the pro-cyclicality of programs to support people in bad times, and

4. the demand for most of the functions of state government (e.g. road maintenance, prisons, education, etc) don’t really depend much on the business cycle

I.e. what you are proposing makes perfect sense irrespective of the 2009 ARRA, so I would drop the “instead of” and say it’s a good idea, end of story.

OK, I should start by noting that my current rhetorical hobby-horse is one person’s declaration that another person missed a point, misunderstands, doesn’t get some idea, simply because the other person has not given the same attention to that point or idea as, in this case, Bob_in_MA things it deserves.

There is absolutely no chance that the guy who has been running around saying “liquidity trap”, first about Japan and more recently about the US and the UK, has somehow left debt out of his thinking. This is the guy who identified zombie banks as critical problem in Japan’s lost decade. Zombie banks are the result of bad debt being held on bank books.

It is quite unlikely that Krugman has misunderstood the role of debt in this recession. What he is doing is urging that a shortage in private sector spending – the result of high levels of debt and a sharp drop in net worth and bad debt on bank books, among other things – be made up by government spending, financed through the issuance of sovereign debt. When, underneath it all, Krugman is urging that one form of debt financed spending fill the gap left by another form of debt financed spending, it is hard to believe he has ignored the role of debt.

There are plenty of ways to get other ideas into a debate than to declare that some other person’s thinking is deficient. One advantage to doing in with “as regards Krugman’s comments, I would like to put greater emphasis on the role of debt” is that you don’t need to pretend to know what is in the other guy’s head, to pretend to have read and absorbed everything the other guy has written, said or thought on an issue. ‘Cause when you get right down to it, declaring that the other guy is deficient in his thinking on some point does require that you know everything he has written, said or thought on the issue.

If you believe in Say’s Law, Krugman is right. Excess demands must sum to zero, so the boom is Sector A must be matched by a decline in other sectors.

In an economy with money, you can have an excess demand in sector A without excess supply in some other real sector if and only if you have an excess supply of money. That’s not a bad summary of what a lot of people think actually did happen.

Jeff: I think of Say’s Law as the necessary implication resulting from aggregate summation of private budget constraints. All of these hold and all markets clear in the model I reference, and yet it is the case that a drop in the demand for sector A output results in a drop in the aggregate quantity of goods and services produced. There is no “excess supply” in sector A– employment there falls until the marginal product of labor in sector A equals the unemployment compensation rate.

@Bob_in_MA,

Krugman’s 2002 column was just one example of his trademark gloomy sarcasm. (People who have trouble discerning this seem to be notably deficient in the sense of black humor department.) Here’s what Arnold Kling said about the matter:

“Krugman was mainly expressing pessimism. He was not cheerfully advocating a housing bubble, but instead he was glumly saying that the only way he could see to get out of the recession would be for such a bubble to occur. … In the event, we had a housing bubble and we got out of the recession. To me, this raises the question of whether a distorted recovery is better than an undistorted recession.”

http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2009/06/defending_what.html

And that’s the way I remember reading it while glumly chuckling at the time. The phrase “asset bubble” has no positive connotations to Krugman or anybody else who is remotely sane. In the original column Krugman referred to Paul McCulley’s statement that Greenspan would need to create another bubble (the last one having been so much fun). Krugman revisited McCulley’s predictions in 2005:

“In July 2001, Paul McCulley, an economist at Pimco, the giant bond fund, predicted that the Federal Reserve would simply replace one bubble with another. ”There is room,” he wrote, ”for the Fed to create a bubble in housing prices, if necessary, to sustain American hedonism. And I think the Fed has the will to do so, even though political correctness would demand that Mr. Greenspan deny any such thing.”

As Mr. McCulley predicted, interest rate cuts led to soaring home prices, which led in turn not just to a construction boom but to high consumer spending, because homeowners used mortgage refinancing to go deeper into debt. All of this created jobs to make up for those lost when the stock bubble burst.

Now the question is what can replace the housing bubble.

Nobody thought the economy could rely forever on home buying and refinancing. But the hope was that by the time the housing boom petered out, it would no longer be needed.

But although the housing boom has lasted longer than anyone could have imagined, the economy would still be in big trouble if it came to an end. That is, if the hectic pace of home construction were to cool, and consumers were to stop borrowing against their houses, the economy would slow down sharply. If housing prices actually started falling, we’d be looking at a very nasty scene, in which both construction and consumer spending would plunge, pushing the economy right back into recession.

That’s why it’s so ominous to see signs that America’s housing market, like the stock market at the end of the last decade, is approaching the final, feverish stages of a speculative bubble.”

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9507E4D61039F934A15756C0A9639C8B63

Now I personally don’t believe that the low fed funds rate was the major cause nor even a major factor in the housing bubble. But to read Krugman’s columns and think he was cheerfully calling for more asset bubbles to drive the economy is, to put it politely, a little dense.

I am just curious. Do we still have any private industry left in the US or is all employment government employment?

Bill Clinton taught us how to how to defeat unemployment. He signed welfare reform slashing the welfare rolls and increasing productive employment. Suddenly these people sitting at home watching Dr. Judy discovered that they were actually happier working, earning money, and being productive citizens. Amazing! But Clinton was so ashamed of solving the problem that he signed it in the dead of night.

Bob in MA and Dan H. – if you’d bother to read the very *next* paragraph, it would be obvious that Krugman was saying the Fed would have to engineer a housing bubble to pull us out of the early naughts recession – a feat Krugman didn’t think the Fed would be able to pull off. As he puts it in the last paragraph, “But wishful thinking aside, I just don’t understand the grounds for optimism. Who, exactly, is about to start spending a lot more?”

The only thing Krugman got wrong there was being overly pessimistic about the Fed’s ability to blow up a housing bubble. But don’t let the facts get in the way of your personal bias!

Great post, and many great comments.

It seems intuitively obvious to me that there is a lot less friction involved in pulling people into relatively high-paying jobs in sunny climates, as opposed to pushing them out of those jobs and into a confusing and uncertain market. One big lubricant is the simple narrative that reduces information costs – anyone can understand that the construction industry is hiring in Arizona and Florida, and if that happens to be true most of the time, the results will be powerful. There is no such narrative operating now.

KJMClark

“But wishful thinking aside, I just don’t understand the grounds for optimism. Who, exactly, is about to start spending a lot more?”

Greenspan didn’t explicitly say he was out to create a housing bubble….in fact he was denying there was one up to his very retirement day.

But early on he did make comments which indicated where his head was at, like “the consumer is in pretty good shape(meaning consumer credit levels) and “our housing stock is old”.

The problem of the day was corporate debt was at very high levels after the corporate “investment” boom of the 90s. So I think Greenspan thought the consumer could take up the debt growth slack from corporate debt growth.

Today of course everyone, including Krugman, think the USG will be new engine of debt growth.

I know debt growth is not an official economic word. I think the correct substitution is aggregate demand.

I think where Krugman goes wrong is saying capital was poured into housing. It wasn’t. The housing bubble created resources, at least on paper, and banks were willing to lend on that created capital helping consumers ‘feel’ more wealthy and helping drive other consumer spending. To the extent that capital was reallocated from other sectors to housing, it was negligible. Do rising stock prices draw capital from other sectors of the economy? No, it draws it from other investments or from under the mattress but, not from auto production or coffee sales. How many houses were actually built during this time. How many would have been built without the bubble. That is the only resources diverted to housing.

Jim,

Let’s cut to the chase. The consumption share of U.S. GDP no longer will be 71% of GDP and may fall back to levels in the 67% range. The change in U.S. consumption will have major impacts domestically and internationally.

Focusing more specifically on the U.S. economy, it’s clear that changes in U.S. consumer consumption patterns will impact a multitude of domestic economic considerations including available taxation revenues from sales of goods and services to employment levels.

We will hear all sorts of ideas and chatter to counteract the reduced spending levels of consumers, but none are likely to have any major impact on returning consumer purchases to previous levels. And we’re going to hear all sorts of employment ideas including incentives for creating job growth in businesses. So, we’ll spend money pursuing some of those ideas, but very little will change on the consumption front.

This is where we are and where we are headed unless there is a major positive change in the structure of the U.S. economy. Don’t expect that to happen any more than we should expect major changes in U.S. trade policy.

What will fill the U.S. GDP loss due to reduced consumption? It could easily be a 4% hit. This is the question which deserves serious attention.

“How many houses were actually built during this time. How many would have been built without the bubble. That is the only resources diverted to housing.”

Its not just houses. Its the things people put in those houses. Its the things people bought on credit with home equity loans. The finance jobs created by the boom and all of the tertiary jobs they created. Its the private equity boom created by cheap funding costs. Etc. Etc. If you can’t see the extent to which the housing bubble affected the entire supply chain I think your a little crazy.

As for Krugman does he ever come out and advocate to just taking ones medicine? No. Its always stimulate this and print that. He never met a recession or crisis he didn’t want to throw money at (you can add the ’98 Asian financial crisis too). Thus he can’t sit back and complain when what he’s advocating goes wrong. He acts as if government planners, if they were as smart as him, would get the stimulus just right and we wouldn’t have a business cycle. Luckily, he is smart enough never to run for office and implement his ideas lest he be judged rather then Monday morning quarterback the Fed chairmen.

Just as corporations taking on too much debt and consumers taking on too much debt ends badly, the same will be true of government. Shifting the debt burden from private to public doesn’t get rid of it. Japan has been doing that for 20 years and they haven’t fixed a damn thing.

There is only on ending to this, and its painful debt deflation. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but I doubt we get through the baby boomers retiring without it. Its not a policy choice, its simply inevitable.

It is a hunch, but I doubt that economists have math models for recent and on-going events because they are so rare. The best mental models come from the corporate sector from the experience of balance sheet driven bankruptcies – as opposed to other flavors. Lehman was profitable until the day it failed from balance sheet failure. The time spans in economies stretch out longer, but similar things can be said – like housing was booming until it crashed, banks were liquid until they weren’t, consumers bought from debt until they stopped,etc. All these are balance sheet driven, and not driven by inventory cycles, profit margins, or revenue changes – the operating stuff of normal economics.

In well run corporate bankruptcies, the first step is to get control of cash flow. We’ve been through the national economic analogue – Paulson and Bernanke stopped the run on the banks. The second step is to close or sell assets that consume cash. The US has not started this step in a serious way. Large zombie banks still operate with almost no changes. Large zombie corporations still operate with little change. Public funding continues to go into them in various complex subsidies. Later, the third phase of well run corporate bankruptcies is to invest the scarce liquid assets in a few businesses that are competitively strong. The US is not even close to this step. Loans (liquid assets) are not available to most companies. Consumers do not have their own balance sheets repaired to an extent that they can buy from growth companies.

When economists, politicians, and the influential public recognize that we have a balance sheet national bankruptcy to repair, we may get some effective action. Effective action will be painful and fought by politically powerful groups, e.g., bank holding companies, subsidized companies, some union driven corporations. Re-use of historical tactics from business cycle recessions is unlikely to be effective. Take a look at Japan’s decade of bridge building to nowhere and see where it got them.

Mike Laird

We have had one small step towards “investing the scarce liquid assets in a few businesses that are competitively strong”. Delphi just emerged from bankruptcy with the help of a few billion dollar cash injection from GM. Zombies helping Zombies. That is soooo sweet it wants to make me cry…as a 61% captive shareholder. Watch out Hyundai, here we come.

Krugman made the comment in a flip way, as he does most things. But to voice doubts about whether Greenspan could pull it off, doesn’t really change the gist of the original comment. The piece is attacking Greenspan’s capabilities, not his intentions. If you read that as a warning about the dangers of a housing bubble, you’re being pretty generous.

“Nobody thought the economy could rely forever on home buying and refinancing. But the hope was that by the time the housing boom petered out, it would no longer be needed.”

That comment from the latter column, makes it sure sound like he didn’t see an artificial boom as problem, until it went on too far. So, three years later, at the bubble peak, he sees the monster it became. bravo.

My point isn’t that Krugman is the Antichrist. It’s that he doesn’t see increasing debt levels as being much of a problem now. He’s had several pieces on the subject, comparing public debt levels to WWII, etc. Usually in the same flip manner.

But he didn’t see the problem then until the fat lady had sung. So maybe this is something he really doesn’t have a handle on?

I have no idea how things will turn out, but I don’t have any faith that Krugman does either.

If workers are uncertain of future demand in almost all industries they can think of (pace the daily spam I get in my inbox claiming booming opportunities for Radiology technicians), they may not be able to formulate a rational plan for re-training.

Well, there are “lagging bubbles”, such as health care and education, IMO. “Re-training” (generically) designed to land people jobs who were formerly in manufacturing and to transfer them into medical related jobs is a good example. The problem with this is that we are over-treated with exotically expensive medications that often don’t work and scanned by overpriced machinery that isn’t often necessary. When the plug gets pulled (soon) on this, the demand for all those technicians and the people needed to train them is going to go negative despite the demographics. Bottom line: Until we have a fairly (much lower valued) dollar and start producing a lot more of the own ordinary stuff we consume every day, we are going to be in a world of serious hurt.

James,

I think the picture (and the idea to create it) belongs to a guy called Michal at Innocent Bystanders, and not from Greg.

http://michaelscomments.wordpress.com/2009/10/02/september-unemployment-the-job-loss-accelerates/

Bob_in_MA

bon dit

Movie guy –

Good comments. Too bad about trade. The current international imbalances (which have not been cured – they are just growing more slowly) are due in no small part to currency policies abroad. It is simply too bad that we seem to be of a mind that nothing can or should be done about them. They are protectionist in the extreme – equivalent to monster export subsidies combined with huge import barriers. How’s come its OK for them guys, but not OK for us to push back?

@kharris

Say’s Law only holds in certain, specific situations. In situations where I falls out with S (as happened earlier in the decade), Say’s Law no longer applies. You can, for a time, have your cake and eat it, too.

In nearly all discussions of debt, and the problems facing future generations in dealing with the debt, the debt being referenced is the public debt. But I would argue that all debt, economically speaking, is the same. All debt, whether public or private, must be paid with the production, either past (savings) or present (current consumption), of goods and services since the goods and services produced are the only real wealth an economy can know. The economy cannot tell, and doesn’t care, who does the borrowing. We should quit separating the federal debt as if it is the only debt that matters and instead focus on the total debt of the non-financial sectors which in June of this year was over 2.4 times GDP. The federal debt, in real terms, per capita, or as a percent of GDP, is not at record levels. The same cannot be said of the total debt.

They are protectionist in the extreme – equivalent to monster export subsidies combined with huge import barriers. How’s come its OK for them guys, but not OK for us to push back?

‘Cuz free free free trade is sacred.

National government supplementing state government, state government supplementing local government… terrible.

Skip the waste and skimming. Collect money at the level it is needed.

Free or equal, pick one.

Did anyone notice that jobs were cut across almost all industries at once? That’s pretty strong evidence for “cyclical”.