On Monday the Federal Reserve proposed a new term deposit facility that would allow the Fed to borrow directly from private institutions. Here I offer some thoughts on how this fits into the Fed’s long-term plans and what its implications for the rest of us might be.

Let’s begin with some background on how we got here. The Fed’s conception has been that the core problem we have been going through was a credit crisis– banks stopped lending and institutions stopped buying mortgage-backed securities, as a result of which businesses and consumers could not borrow adequate amounts. The Fed’s goal was to step in where private lenders would not, with the Fed initially lending directly to private banks through a new term auction facility and to foreign central banks through currency swaps, supporting issuers of commercial paper through the commercial paper funding facility, and lending broadly through a number of other new facilities. During 2009, these new programs were largely phased out and replaced by outright purchases of mortgage-backed securities and agency debt. The graph below details the asset holdings of the Federal Reserve over the last three years. Fed assets more than doubled in the fall of 2008 and remain at those elevated levels to this day.

|

Where did the Fed get the funds to do all this? At one level, the answer is simple– the Fed simply created the funds, unilaterally declaring that the seller of the asset or recipient of the loan now had a corresponding increase in that institution’s balance with the Federal Reserve. Those balances ultimately represent claims on green U.S. dollars, which the banks holding the credits could at any time request the Federal Reserve to deliver to the banks in armored vans. It is an accounting identity that any purchases or loans by the Fed necessarily have the consequence that the dollars thereby created must end up somewhere. One can therefore equivalently summarize the actions of the Fed in terms of the liability side of its balance sheet, which consists primarily of the credits created or dollars delivered. The graph below summarizes Fed liabilities over the last three years. The height of the graph for each week is by definition the same as that of the previous graph. Whereas the first graph summarizes what the Fed is holding, the second summarizes who is holding the stuff the Fed has created.

|

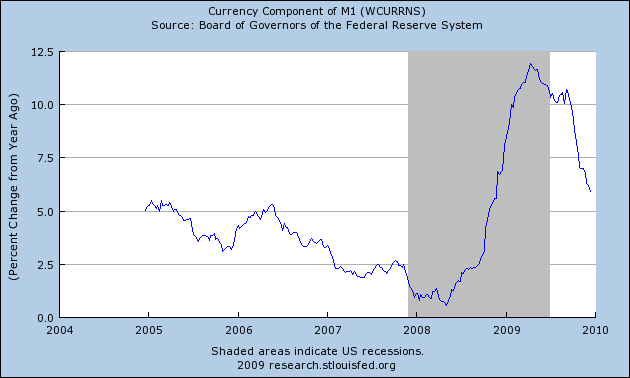

In normal times, the credits created by the Fed would not be held passively by banks at the end of the day, but would be actively lent out in a process that ultimately would result in the credits ending up as cash held by the public. However, so far there has been only a modest boost to currency, with the vast majority of the funds created by the Fed sitting idle at banks, represented by the green area in the graph above.

|

If banks were to return to the historical patterns of managing reserves, the trillion in excess reserves would end up as circulating currency with dramatically inflationary consequences. So there has been considerable discussion within the Federal Reserve of an exit strategy, or how to undo the doubling of the Fed’s balance sheet. Plan A is that the problem will take care of itself. As the economy improves, the need for the Fed to hold on to these loans and assets diminishes, and the Fed would stop rolling over loans and sell off assets to destroy the reserves it had previously created.

But there’s always been a serious question as to whether the Fed would risk sabotaging a fragile recovery by removing its support too quickly. For this reason, Fed officials have a number of backup plans in mind. The Fed set the stage for one of these by introducing the policy of paying interest on reserves in the fall of 2008. One of the reasons banks are content at the moment to let the reserves created by the Fed stand idle overnight is that, unlike the earlier rules, banks now earn interest on those idle balances. If banks become less willing to hold those surplus funds, the Fed could simply raise the interest rate it paid on deposits to whatever it took to persuade the banks to keep the reserves in their account with the Fed. In effect, reserves held in account with the Fed today function just like treasury bills. But whereas bills are used by the U.S. Treasury to borrow from the public, reserves are used by the Fed to borrow from banks, the proceeds of which borrowing the Fed has used to purchase MBS.

The problem with raising the interest rate as an exit strategy is the same as the problem with Plan A– the Fed is unlikely to want to raise interest rates as long as significant risk of a double downturn remains. Last summer Bernanke also detailed two other possible tactics, both of which again amount in effect to direct borrowing by the Fed. Initial steps to implement both of these have subsequently been announced by the Fed.

The first strategy would use reverse repos, which are essentially collateralized short-term loans from private institutions to the Fed. These are currently at around $60 billion, though the Fed has conducted preliminary steps for implementing these on a much bigger scale if need be.

The second strategy is Monday’s proposal for a term deposit facility:

Under the proposal, the Federal Reserve Banks would offer interest-bearing term deposits to eligible institutions through an auction mechanism. Term deposits would be one of several tools that the Federal Reserve could employ to drain reserves to support the effective implementation of monetary policy.

This proposal is one component of a process of prudent planning on the part of the Federal Reserve and has no implications for monetary policy decisions in the near term.

Like the expanded reverse repos, currently this still appears to be in the nature of contingency planning, getting the apparatus in place if needed. But it is the most direct implementation of the essence of the other two devices, namely, the proposal is for the Fed to borrow directly from the public in order to be able to support the prices of mortgage-backed securities and agency debt.

We sometimes describe fiscal policy as determining the overall level of the public debt, while monetary policy determines the composition of that debt between money and interest-bearing federal obligations. By that definition, the Fed has clearly now entered the realm of implementing fiscal policy, by issuing debt directly in the form of interest-bearing reserves, reverse repos, and now term deposits.

The Fed would no doubt argue that it is doing so wisely, and that the decision to absorb Fannie and Freddie’s debt and mortgage guarantees into the fiscal liabilities of the U.S. government has already been made by Congress and the President. The Fed is simply taking that reality as given and trying to minimize collateral damage.

Or one might see it this way: political pressures had been the cause of the quasi-nationalization and then de facto nationalization of mortgage debt in the first place, and the Fed found itself inextricably drawn into the mess. There is now political pressure to inflate the debt away, from which pressure the Fed nevertheless sees itself as immune.

But I fear that as this marriage between fiscal and monetary policy becomes consummated, an amicable divorce is not the most likely outcome.

My advice would be the sooner the Fed can return to plain vanilla central banking, the better.

So I think understand the options in a mechanical sense, but I don’t understand how they would be meaningfully different. The collateral for reverse repos would be the Fed’s stash of Treasuries, or other assets (e.g. MBS) that it holds? Does it matter? In a sense, I can’t see the Fed ever defaulting on it’s debts (it can decree money into existence), so I don’t see the difference between a reverse repo, a term deposit, or simply paying interest on excess reserves. Maybe the first two allow somewhat longer-term planning, whereas the third would require inelegant tweaking of the rate paid to maintain a fixed volume of borrowing. But all of them represent the Fed owing money to banks.

The option that looks different to me is the Treasury special funding account — there the Fed owes the Treasury money, which owes the bond-holding public in the form of additional T-bills. But it seems that the decision has been made to wind down this mechanism, and the Fed will borrow exclusively from banks.

And the option that’s not even on the table would be to get the Fed out of the MBS-holding business altogether. Presumably the powers-that-be believe someone needs to do that, and setting up a TARP-like entity to do it, funded by bonds, would require legislation that’s politically impossible. The Fed is the only non-legislative mechanism available for a trillion-dollar intervention in the MBS market.

I think I share Dr. Hamilton’s unease — the Fed’s actions may be necessary, and they may be the only institution capable of taking those actions, but some separation-of-powers arrangements are being seriously breached. (Or, “have been”, past tense seems appropriate).

Very informative. I wonder, if this is indeed fiscal policy, might Congress at least fein veto? … I’m not excited for the inevitable sword-rattling of the Rand-clutching anti-Bernankeists. On the other hand, there’s a definite difference between independent quasi-governmental and independent quasi-monarchal.

Also who is the “public” exactly here? I see the deposits will be available to Eligible institutions including banks, savings associations, savings banks and credit unions that are federally insured or eligible to apply for federal insurance,

trust companies, Edge and agreement corporations, and U.S. agencies and branches of

foreign banks. Does that mean grandma’s going to start giving me TDF’s on my birthday ?!

You wrote “reserves are used by the Fed to borrow from banks, the proceeds of which borrowing the Fed has used to purchase MBS”.

I believe you have this backwards. The so-called excess reserves are the byproduct of the Fed’s purchase of MBS from the banks.

philip mckee

I agree with your version. Buying MBS was part of QE. The way I think QE works is the Fed “prints money” (but we all know that’s done with computers nowadays), then buys MBS on the open market, from banks or anyone else, and that’s how new money was injected into the economy and banking system. Then much of it found its way back to the Fed because the Fed is paying interest on reserves.

The way JDH describes it, if the Fed was borrowing from banks, then buying MBS, this would be neutral on money supply.

But if JDH can prove us incorrect on this point, I would be happy to hear it.

Altogether an interesting article, if one understands it as a description of the Fed’s and mainstream economist’s perception of the problem. I would like to raise one point, though. You write:

“If banks were to return to the historical patterns of managing reserves, the trillion in excess reserves would end up as circulating currency with dramatically inflationary consequences.”

There is criticism out there with respect to this widespread excess-reserves-could-create-(hyper)inflation meme. For instance, one critic is the Australian economist Steve Keen.[1] He argues that this fear was founded in a false believe in the money-multiplier model, according to which bank lending was a function of available reserves (the fractional reserve system), but the money-multiplier model had already been falsified by empirical research in 1990 (with respect to the first point below). The empirical data showed that 1. debt creation happens first and then the reserves are adjusted with a time lag of about one year as needed and 2. the amount of debt created by banks way exceeds the amount of fiat money, in total contradiction how it is supposed to work according to the fractional reserve system.

If this criticism is right then the fear regarding the “excess reserves” as future source of (hyper)inflation isn’t justified. Banks will expand their lending or they won’t depending on the economic conditions, depending on whether they find enough borrowers who will load on more debt and who will be expected to pay off their debt and interest. If there aren’t enough borrowers the excess reserves won’t do anything, if there are enough borrowers a withdrawal of the excess reserves won’t help.

Please could you comment on this criticism?

[1] see http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2009/01/31/therovingcavaliersofcredit/

rc

Banks don’t acquire risky assets unless they have the capital to support the risk/return trade off.

Excess reserves are a risk free asset that are irrelevant to that type of decision.

Paying interest for fixed terms won’t change those capital allocation decisions.

It’s more of a warranted yield curve subsidy for the banking system, which has had the excess reserve position forced on it (as a Fed liability) for an extended period.

Amazingly, this is the correct explanation, from the Economist of all places. It has nothing to do with lending out reserves or creating more currency:

http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2009/12/the_truth_about_all_those_exce

I’m excited to see how “economists” are still in entranced by the monetary reserves–wondering: when the fateful day of bank lending will descend upon us.

If the Fed wanted the banks to lend, they would simply make them lend by charging them fees for holding the monetary reserves. Not only has getting the “credit rolling” not worked, for various reasons, but the Fed doesn’t want it to work–at least not for now.

The Fed will manage to create inflation, but the way they have chosen to do it right now is through monetizing the US debt; one has to wonder how the US managed to borrow $1.8 trillion over the fiscal year, or $1.4 trillion calender. Where did all the money come from? Treasury reports account for the amount, but not the exact source; and that goes for the flow of funds report as well. Is there even enough money in the world to fund these massive US deficits while many others countries are on a borrowing spree? I certainly doubt whether there’s enough capital.

Inflation will take effect through two process: massive government “borrowing”, and the indefinite suspension of the financial institutions to have to recognize losses on their balance sheets (which will possibly prevent deflationary forces from credit and asset depreciation)–and now that Freddie and Fannie have a blank check, watch as they buy mortgages up at over valued prices to attempt to reinflate housing prices.

However, the false beliefs underlying all of this are two fold: (1) market equilibrium, and (2) the shattered remains of Bretton Woods will continue to hold, that is, the dollar will act as a poor anchor in a financial and economic disaster (imbalances and hyperinflation in term of financial instruments, and the over expansion of credit) due to its unpegging from gold and becoming free floating; that instability of currency fluxuation will create too much economic and political turmoil for countries using the dollar as trade. Further, as resources become more scarce, countries will be more reluctant to exchange commodities for freshly typed up monetary units known as the USD. As a matter of fact, the only asset backing the USD is the US Military, and they seem to be busy in and around oil producing nations, maybe propping up the petrodollar concept.

Ultimately, for any plan of Mr. Bernanke’s to have even a modicum of a chance of succeeding, which I don’t suspect it even has that, the dollar MUST remain the World’s reserve currency in order for him to offset inflation by exporting it and distributing it around the World, as opposed to it all lingering within the domestic US.

The Fed is required by law to aim for maximum employment and stable prices. In its most recent public forecast, it effectively stated that it believes maximum employment means an unemployment rate of around 5 percent and that stable prices means a measured inflation rate of around 2 percent. However, it also stated that it will not come close to achieving these goals for at least 3 years. The Fed will not be able to exit until the economy clearly is on track to reach these goals soon. Ironically, more stimulus now, in the form of more asset purchases to push long-term interest rates even lower, will actually enable the Fed to exit from these nontradtional policies sooner than otherwise because it will enable the Fed to achieve its objectives sooner.

Professor Hamilton,

Thank you for the clear explanation. Is this an accurate description of how the Fed expects things to transpire?

– The economy continues to recover and gradually borrowers become more willing to take on debt and banks more willing to lend.

– This lifts the amount cash (currency, M2?) in the system and if this growth exceeds what the Fed sees as a reasonable rate, the Fed uses one or more of the processes you mention to drain liquidity.

But I guess they wouldn’t simply measure the rate of change of the money supply directly, but rather use inflation as a measure of its effect.(?)

Thanks.

I don’t think returning to plain vanilla central banking is an option. Jimmy Stewart (traditional) banking is dead. We now inhabit a brave new world of shadow banks and securitization. Monetary policy is going to have to get to grips with this transformation. And we (economists) don’t yet understand it all that well.

I call this “Maintaination”:

“The artificial support of asset classes by monetary policy that requires participants to accept printed cash as real and trade as such but never to actually ask for the mythical principle.”

I would wonder when the banks will ever want what they gave the FED back on their books. It may be longer than you think.

philip mckee and Cedric Regula: The MBS purchases and reserve creation are linked by an accounting identity, and occur simultaneously– the instant the Fed purchases $1 of MBS, at that exact instant reserves increase by $1. As for causation, there is no question that the Fed is considering the two aspects of the operation simultaneously. In any case, the issue I’m discussing here is that of exit strategy– how can the Fed maintain those MBS holdings without seeing the reserves created get into circulation? And for that question, I think it is entirely accurate to say that they propose to maintain the MBS position by borrowing in the form of interest-paying reserves or the contemplated borrowing through expansion of reverse repos or term deposits.

rootless cosmopolitan: I read the piece by Steve Keen you referenced, and think it has no relevance for the discussion here. I have said nothing about a money-multiplier model. The relevant propositions are whether (1) the supply of reserves equals demand, and (2) the Fed controls the supply of reserves. His argument, insofar as it has merit, is that the Fed has historically adjusted the supply in response to demand. It is not denying the validity of either propositions (1) or (2), which are the heart of my analysis. It is certainly correct that the demand for reserves at the moment is very unusual. The topic under discussion is what will happen “if banks were to return to the historical patterns of managing reserves.”

Bob_in_MA: As for the expectations of the Fed, I refer you again to Bernanke’s public statements on the matter.

JDH,

“The topic under discussion is what will happen “if banks were to return to the historical patterns of managing reserves.””

I do think Steve Keen’s and others criticism is very relevant for what is going to happen. It’s relevant for your statement about the possible “dramatic inflationary consequences” of this return to the “historical pattern”, since this statement assumes debt and money creation in the economy happens according to the model of fractional reserve banking, doesn’t it? What else is this “historical pattern” supposed to be (allegedly lending out the reserves instead of hoarding them) that could lead to dramatic inflationary consequences of base money in the system according to this model? If the causal relationship between “excess reserves” and money creation in the economy didn’t exist, your statement about inflation as possible outcome wouldn’t be valid.

rc

rootless cosmopolitan: Please explain what, in your and Steve Keen’s view, is going to cause the demand for reserves to remain at $1 trillion? By “historical pattern,” I refer to a demand for reserves that is a considerably smaller number than that.

JDH,

OK, you can call it an accounting identity, but I still like to think that I sold my MBS bond fund to Bernanke, he put money in my broker account, I transfered the money to my liquid checking account, using some of it to buy groceries and beer, while my bank sent the rest back to the Fed to get the .25% rate because they don’t want to lend to the other shyster banks in the overnight interbank lending market.

But your explanation is quicker to say.

But I agree with the description of the exit strategy, tho you make it a little confusing when you say the Fed is “borrowing” from banks. I guess that is technically correct, but common parlance is “drain liquidity”.

Ben has been saying he prefers not to sell MBS, and there is the potential bottle neck problem with trying to drain the extra trillion in base money created in the last year and a half all thru 19 primary dealers. That is why they have been talking broadening the base of banks they would deal with by offering term deposits. They also were talking about going straight to money markets as well, but I haven’t heard more on that lately.

JDH:

I can’t present Steve Keen’s view on this here. And I also don’t really understand the question. Maybe I am mistaken with respect to something. Why do you say the “demand … remain at $1 trillion”? I thought the bank’s deposits on the central bank’s accounts (the “reserves”) was 1 trillion. But this isn’t really a demand, is it? It’s an accumulated amount, like a stock. It’s not a flow variable.

Why did the banks accumulate this amount of deposits with the central bank? I would say because the opportunity has been provided to the banks. The opportunity for banks to get rid of bad assets, since the Fed so generously offered to buy these 1. to provide the financial institutions with liquidity under the assumption the crisis is mainly a liquidity crisis, and 2. to “get the banks lending” again, exactly based on the false presumption lending was a function of available reserves. However, banks didn’t start lending again, they are just holding the proceeds from the sales of the securities as deposits in their central bank accounts. If the banks were to expand lending again sometime in the future, they could withdraw these deposits, but there isn’t any causal link between these deposits and the amount of lending and (dramatic) inflation, which you said was a possible outcome. If the banks expanded lending again and create new credit money in this way again, they would do it anyway with or without these excess reserves. Thus there is a possibility of future inflation, but not because of the excess reserves and a return to the “historical pattern” of managing these.

rc

Hmmm. What price is the Fed buying the MBS’s at? Face or market? Who will end up eating the presumed loss on the MBS’s, the Fed or the banks? If the Fed bought them at face value and has to re-sell them at market (let’s say, for 1/3 less on average to correspond to drops in housing values), does that not imply that the banks get to keep one-third of the reserves as a freebie? Or am I misunderstanding this?

I don’t see the magic here.

Inflation is caused by banks making loans. They make loans because they believe the spread between their cost of capital and the interest rate paid by borrowers more than compensates them for the risk they bear in making the loan.

As the economy improves borrowers will demand more financing at a given interest rate. In my mind, the only way to stop banks from meeting this demand will be to increase their cost of capital (I thought this was called raising interest rates).

I thought that money was only lent to the Fed because it was more profitable than lending to consumers/businesses. If lending to consumers/businesses gets more profitable how can the Fed maintain the balance of excess reserves without making lending to the Fed more profitable as well?

Can somebody help me?

rootless cosmopolitan: Every asset is a stock. Reserves are an asset like any other. Their demand results from a portfolio balance calculation, just as does the demand for any other asset. Regardless of how you came to accumulate the reserves, you have an active decision at the end of the day whether you want to hold them or whether you want to use them to buy something else.

Supply has to equal demand for this asset, just like any other asset.

Rootless – good points.

The demand argument doesn’t work because it doesn’t apply at the level of the banking system as a whole. System reserves can’t be “used” by banks to buy something else.

JKH: That’s exactly the sense in which the supply is controlled by the Fed. A fixed supply does not make demand irrelevant.

JDH:

And if I decide at the end of the day to hold my assets of 1 trillion dollars at the same level, both supply or demand for these assets that comes from me is exactly Zero. The amount of demand/supply equals the change in the portfolio balance, not the price sum of the portfolio balance itself.

Actually, we are digressing now from the causal relationship between excess reserves and inflation.

rc

This BIS paper argues demand for excess reserves is infinitely elastic when reserves are compensated at or near the policy rate.

Which would imply terms deposits aren’t necessary.

http://www.bis.org/publ/work292.pdf

rootless cosmopolitan: No, if you decide to hold $1 trillion, then demand equals $1 trillion.

I’ve done some additional reading, but I still have a question…

How does the public benefit by the Fed using the Term Deposit Facility as opposed to the Fed changing the interest rate paid on excess reserves?

I would be very appreciative if someone could help me understand the benefits of this new policy initiative.

JKH,

“This BIS paper argues demand for excess reserves is infinitely elastic when reserves are compensated at or near the policy rate.

Which would imply terms deposits aren’t necessary.

”

I don’t think they are, if you assume the Fed just wants to pay whatever “X” on reserves that keeps them at the Fed.

But I think they really want to drain liquidity without raising the Fed target rate too high. Thinking about things like “high power money”, money multiplier and velocity, they are probably worried that things could get out of hand quickly with more than double the normal amount of base money in the system. They usually don’t like raising rates high and fast for a number of reasons, so if they can tie up excess reserves another way that would be easier for the real economy and financial world to handle.

Also paying interest costs them money. There is a limit to how much the Fed makes on their balance sheet.

Which is another thing that annoys me. In China they just raise reserve requirements. That’s free, but in the USofA, the Fed pays interest to the scoundrels, after buying their bad loans. Actually, BECAUSE they bought their bad loans. No wonder all our Ivy League schools are turning out nothing but bankers.

CR,

Good points.

I think they’re paying interest on reserves because they need to in order to maintain a lower bound on the Fed funds rate. And the reason they’re paying 25 bp instead of zero when the Fed funds rate is close to zero is simply to set the precedent that they’ll be paying when they start to increase the fed funds rate.

The Fed has assets on which it is earning interest and can afford to pay interest to the banks at what is essentially the risk free rate because it’s making a spread. That’s fair ball.

It’s only paying about $ 2.5 billion a year in interest now; that’s immaterial relative to TARP.

So they’re paying interest as a function of interest rate management; not reserve management.

Banks as a whole can’t “use” up reserves by “lending them” because the Fed controls the level of reserves.

Banks also know this.

And they know they have to make decisions on allocating risk capital in order to take on new risk assets. That’s got nothing to do with reserves. The banking system doesn’t “lend reserves” to non-bank clients, and it doesn’t “use up” reserves in lending to non-bank clients.

As I said earlier, the Fed is basically giving the banks a break with what will probably be a small amount of yield curve compensation, while it still has the excess reserves in place, given that it has forced the excess reserve position on the banking system in the first place.

But I fear that as this marriage between fiscal and monetary policy becomes consummated, an amicable divorce is not the most likely outcome.

Thanks JDH for a very spicy simile, your wordsmithing approaches verse!

I would like to interject my theory about the entire mortgage security brouhaha… The US government found it convenient for the FED to absorb the agency and mortgage securities since it eliminated fraud suits in federal court and testy diplomatic relations overseas…. Domestic primary dealers found it convenient, since they could unload illiquid over-priced securities for cash suitable to satisfy their reserve requirements and hedge-fund loans to pump-up security markets…

Its interesting that the FED executed the direct purchase of the MBS rather than have the exercise done through the P-PIP program with TARP funds. Could the reason be political? Would too much dissent have occurred if the policy had been executed by the treasury? In my opinion, the result is the same: More cash in the system yielding more inflation.

I believe that the more important issue is when Basel III rules get adopted as advertised. Reserve and capital requirements are likely to tighten on banks. The current policy of the FED works nicely to subsidize re-capitalization of legacy banks via dilution of dollar assets. This is similar to how unregulated mortgage securitization re-capitalized the US economy via dilution of real estate assets.

The other important thing here is that the Fed wants to offer term deposits in part for its own interest rate risk management. It wants the flexibility to exit the reserve position at its desired pace and at the same time raise the Fed funds rate at any necessary pace, and it wants to avoid putting pressure on its own interest margins under any corresponding contingencies. Offering the banks fixed term deposits provides interest rate risk protection for the Fed because it slows the pace at which the Fed’s liability costs will increase in conjunction with an increase in the Fed funds target and the corresponding overnight interest rate on reserves. So self-preservation is also part of the motivation.

The starting point for the correct analysis is that excess reserves are far more important to the Fed as a liability than they are to the banking system as an asset. It’s using these reserves as the liability offset to its extraordinary asset expansion.

Like it or not, the Fed wants to pay an economically fair interest rate (essentially the risk free rate) to the banks for an excess reserve position that has been forced on them “exogenously”, and to put in a lower bound on the Fed funds rate in doing so. It wants to protect its own interest margins by locking in some term funding if it needs to increase the fed funds rate. And it doesn’t want to give the banks the opportunity to make any argument that they’re not paying enough interest to their customers because they’re not receiving it from the Fed.

Also, the notion that the Fed issuing term deposits “drains reserves” is a red herring. The only difference between Fed deposit liabilities to the banks and interest bearing excess reserves is interest rate sensitivity. It’s all excess deposits from the banks’ perspective.

Hmmmm …

I dunno, I don’t see those reserves ever getting back the the Fed. Sorry, but I suspect the Fed’s liabilities are just bank IOU’s.

That’s why last year’s reverse repo ‘experiment’ failed. The banks didn’t and won’t pony up the cash. The armored trucks took it all. It is in anonymous storage lockers all over the country.

You don’t think the bankers are dumb enough to put their hard earned (stolen) cash in a bank, do you?

Nobody is going to run a Ponzi scheme and give the money back at the last minute.

As far as it goes, the Fed will never call for the reserves, so the fraud is secure. The economy will not recover – we are in the beginning of an energy crisis not a credit squeeze. The next leg down is finance unmasked, it cannot pull barrels of oil out of a hat …

The graphics are unbelievable. What a cluster. Is the Fed doing as good a job as they were in 2004, when I was cut off from posting on this site for saying the emperor had no clothes on ?

I’m not sure what your trying to say. My take on your PHd analysis is that you like to stay firmly in the obvious, careful not to break any eggs by saying the Fed is wrong and has been for 50 years.

Why is the Fed paying interest on bank reserves. That is the starting point. They shouldn’t be.

1) The purpose of buying up banks’ distressed assets was supposed to be to encourage (enable?) them to lend.

2) Paying interest on banks’ reserves would appear to discourage them from lending (to customers other than the Fed).

Either:

-the first objective has been abandoned: or

-the Fed is working at cross purposes with itself; or

-I don’t understand something basic.

Is it that, having overpaid in the process of providing liquidity, the Fed can’t allow that much liquidity to “get out” into the real economy without a big pulse of inflation?

If so, is this because responses to liquidity crises are essentially guesses at the location of a narrow safe path between deflationary disaster and inflationary disaster?

This past year, however, we have been bombarded with historical examples of supposedly successful responses, seeming to imply that there is a high-confidence best practice.

Would Professor Hamilton or someone here explain?

Cedric, you nailed it with your “Because…” I think I get the “borrowing” statement.

But I’ll add on to what Steve K asks above in a different slant–instead of doing reverse repos now, why didn’t the Fed do that initially with MBS? Draining reserves would then have been a fait accompli, no?

Did anyone ever find out what the Fed paid for those MBS, par or a haircut and if sheared, by how much?

1) Banks collected fees for selling and reselling impossible mortgage backed financial instruments to each other, and to pension funds, and to foreigners. Using derivatives, they sold each asset to multiple buyers.

2) The impossible mortgage backed financial instruments began to implode.

3) The central bank bought and continues to buy the impossible mortgage backed financial instruments at face value, knowing they are already underperforming and will not likely approach face value ever again.

4) Proceeds from the sale of the impossible mortgage backed financial instruments are being held in interest bearing central bank accounts.

The net result is that the banks created a bad product, which the central bank is buying with loans from the banks.

Can I be a bank?

CK-

There were many purposes to the FED’s buying up the banks’ bad debt: 1. Providing capitalization so that overleveraged bank holding companies would conform to FED and FDIC reserve requirements. 2. Provide a functioning market for distressed mortgage securities, and by extension provide price support to the real estate market. 3. Provide a huge reservoir of ready cash in the banking system sufficient to overwhelm fears that the next crisis would not be handled expeditiously.

IOER is primarily a method of providing profitability to the banking industry during a period of deleveraging and recession. Belief that it serves as an incentive to keep excess reserves out of the loan market is more myth than reality.

JDH,

I appreciate your posts and blog very much. Please tell me what you think of my understanding of this situation, outlined below. To me, the actual threat of inflation is the amount of money by which the Fed overpaid the banks for the MBS and other assets it accepted from them in exchange for reserves.

First, here is how I see the process:

1. The Fed purchases assets (Tbills, MBS) from other entities (Treasury, banks, etc..).

2. The Fed pays for these assets by crediting the entities account with reserves. The reserves is something that the Fed essentially invents and is the modern-day version of printing money.

3. When banks feel comfortable with the decision-making processes they have in place, banks draw down these reservers and lend them out to companies, individuals, and other entities. This is how money becomes currency and where it actually takes the form of printed currency (not in the literal sense but in the sense of assets that can be spent and used to obtain goods).

But I dont see any new money being created here directly. What I see are assets that have merely changed hands. Banks used to have a whole bunch of MBS and other assets and now they have reserves. If they want to get these assets back, they have to pay for them with reserves (which is one plan for bleeding off the reserves).

So the only way that money in the traditional sense is being created is if the Fed overpaid for the assets it purchased (like MBS). In that case, the entities that sold these assets were given a de-facto gift of reserves by the Fed b/c they received above-market value in the sales.

So when gauging the real threat of inflation, it appears that it is not in the total amount of reserves created but in the amount by which the market value of the assets the Fed bought from the banks recently (such as MBS) has been overestimated. And that is something that it seems we wont know for a long time

JKH,

A very sincere thanks for all your wisdom and patient efforts in engaging in these comments discussions on several different blogs. It truly is a service. I hope you never choose to bow out of the debate (due to snarkiness, arrogance from others etc.). The audience for your views is obviously much larger than fellow posters and the stakes are very high.

Jonathan,

Very kind of you to say so. Thanks.

Rob,

“But I’ll add on to what Steve K asks above in a different slant–instead of doing reverse repos now, why didn’t the Fed do that initially with MBS? Draining reserves would then have been a fait accompli, no?

Did anyone ever find out what the Fed paid for those MBS, par or a haircut and if sheared, by how much?

”

The way reverse repos work is the Fed first needs to have some stock of the security. In days of old (pre 2008), the Fed had stock of T-Bills and when it wanted to control short term interest rates it would do repos or reverse repos with the 19 primary dealers. This is a short term agreement to buy or sell the securities in the not to distant future at a guaranteed price with a small guaranteed profit margin. (irregardless of market price of the underlying security, up or down) In normal times this would allow them to influence short term rates by adjusting cash in circulation.

The Fed did use up their stock of treasuries in implementing some of Ben’s other very special programs, so they ran out of ammunition there.

So the order of events is crucial in putting the proper spin on who is borrowing from whom. In March 2009 the Fed announced QE and that part of it includes buying $1.4 Trillion of MBS. The reasons for doing this are stated above by

MarkS at January 1, 2010 10:35 AM, but I’ll highlight that the Fed also wanted to influence long term rates in order to prop up the housing prices.(Ben has a Hercules Complex, methinks)

So this is how the Fed ended up with their stock of MBS. The problem now is that MBS are long term, and the money the Fed bought them with is out there and won’t come back to the Fed for a very long time (a small? percentage, never). However, some of Ben’s other programs were short term in nature. and they are “rolling off”, and this is working in the direction of draining liquidity. So at this point the Fed is considering ways to manage the volume of base money and short term interest rates. Reverse repos using MBS as the underlying security is one way, but there are concerns about whether they can do such a large volume working thru only the 19 primary dealers.

As far as the price paid for MBS, I was under the impression that the Fed bought these on the open market, but I could be wrong about that. Traditional AAA MBS prices did not get nailed that bad, at least for very long. In normal times the default rate was below 1% and it crept up to over 3% just lately. It’s not subprime, tho if “jingle mail” catches on among the masses we have a $8 trillion problem.

The things to really worry about is the other Fed programs where they took AAA(wink-wink) CDOs that are subprime, the $200B in GSE corporate debt which is worthless, except the USG seems intent on guaranteeing it, and the worse transgressions are done by the Treasury because they are not constrained by the same rules as the Fed, who are required to take AAA collateral(laughable as the ratings may be) before printing up money and handing it to banks.

So in the grand scope of things I worry more about what the Treasury paid for F&F, Citi, BA, AIG, GM, Chysler, and to a lesser extent TARP. And the news here is many of the deals went sans haircut.

MarkD-

When the FED buys mortgage securities with FED reserves (cash), the quality of the bank capital, hence its potential multiplier in the fractional reserve banking system is increased.

Under Basel II rules, MBS have a probability of default, consequently cash reserves must be held to cover this “Value At Risk”. For instance, if the default risk on a MBS security is 50%, and the FED reserve requirement is 10%, a $1-Billion MBS bank asset can potentially become 1B x (1-0.5)/0.1 = $5 Billion in transaction deposits. Alternately, replacing the impaired MBS with FED reserve credits (which carry 0 risk), the bank can create $1B x (1-0)/0.1 = $10 Billion in transaction deposits. In other words, the potential money supply (or available credit) is doubled in this example by replacing risky MBS with solid FED reserves.

Note- the important concept here, is that the money multiplier is contingent on the risk of the assets that the banking system is holding. Also, worth mentioning, is that Basel II puts limits on the amount of risky securities that can be used as bank capital (reserves)… Cash, US Gov. debt & FED credits (TIER 1) are unlimited, other securities (TIER 2) must be less than or equal to Tier 1 capital.

There are plenty of CDOs that were discounted 90% or more by the open market and subsequently purchased at par by the FED. Consequently, the FED MBS purchases provide far more subsidy to heavily impared banks (investment banks with low quality MBS), than to banks with higher quality MBS.

MarkS,

I did come across an FDIC statement a while back that about $60B of AAA rated CDOs were held by regional banks as Tier 1 capital, and that was considered kosher by regulators. So Tier 1 is not as squeaky clean as you might think.

Also, news recently came out that Goldman management decided that 2007 would be a good year to start shorting CDOs, so not all IBs needed federal assistance.

Then I forgot to mention the FDIC is guaranteeing the bonds the banks are issuing to pay back TARP. Isn’t check kitting still illegal?

And one more thing, “mark to market” has been relaxed to “mark to make believe”, if you can prove to your friendly regulator that it’s cash flow that matters, not capital…..

Anyone want to buy some bank stock?

Cedric Regula-

Thanks for the clarification on what stood for Tier 1 assets in the good-old USofA… Basel II looked semi-logical on paper, until the system was annointed as self-regulated by the investment bankers themselves- (The SEC’s 2004 Consolidated Supervised Entities program). Rather like having the foxes guard the hen-house.

Personally, the 2001 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, was my favorite. By elevating derivative clearing to immediate resolution and independent of bankruptcy protection, a slice of all subordinated debt could be mutated into a triple-A security. Once so classified, some part of the feckless bank regulation system could be found to look the other way as it was reported as Tier 1 capital.

Actually, I never considered either the more recent BIS or FED definition of Tier 1 capital as “squeeky clean”. The revised definitions provided a method to increase bank profitability by substituting a higher yielding, riskier securities for free cash as a reserve. In the process, the tier 1 definition change reduced the safety of the banking system.

I would like to thank you Cedric, your comments are always erudite, ethical and entertaining. Hope I have the pleasure of shaking your hand some day.

MarkS,

thanks for the response. I get the multiplier effect but and the increased ability to lend that Fed reserves vs. MBS create. At the moment, however, the banks are generally hanging on to their reserves so the increased amount of money supply is a problem only in theory. (I understand that this can change quickly but for now it’s not a problem).

But it still seems to me that the majority of the increase in the Fed’s balance sheet came from purchases of MBS. And the key question there is by how much the Fed overpaid for these assets by getting them at par. If the overpayment is minimal, these assets can be sold back into the market and drain pretty all the reserves that were created with their purchase. So, until the banks decide to make more loans, the additional creation of “money” is equal to the amount by which the Fed overpaid for MBS assets.

Of course, at what markup the Fed bough these assets remains a guessing game. However, if a significant portion of the MBS are ’09 vintages with low prepayment risk then the Fed could potentially make money on selling these back to the markets in a few years.

Thanks Cedric–

Perhaps I’ve got my terminolgy all confused. I was only asking why the Fed didn’t initially say, “I’ll take your MBS off your hands for a period of X, and give you cash. At maturity of period X, you gimme back my cash (money is then destroyed at the Fed), and take back your MBS.”

There would then be no need for their reverse repo mission today? Or am I missing something?

Thanks again

I have only 2 questions than I’m out as my place is not here (understand too little of all this mess).

“Here I offer some thoughts on how this fits into the Fed’s long-term plans and what its implications for the rest of us might be.”

1) To me, all these programs sounds like “black magic”; will all this soup of programs from FED save the day or is just simple guessing? Making them as complicated as possible is any better? Why?

2) What are those implications for the rest of humans like me? As you don’t describe them finally…

MarkD-

Good luck on the chance that “a significant portion of the MBS are ’09 vintages with low prepayment risk”. The stuff that would improve bank balance sheets was ’04 – ’07 vintage, that included unhealthy slices of sub-prime and adjustable rate mortgages.

We will all take a bath on these purchases. Only deflation will make the yield on these MBSs look attractive relative to their risk and performance without discounting their sale price…. We know that the government and the FED will never allow deflation, and they will never admit a loss on the MBS purchases. Consequently we can conclude that the FED will hold the MBSs to term, and the 1.4 trillion will stay on the FED’s balance sheet forever. I would also predict that money supply will be controlled by redefinition of acceptable reserves (Basel III), and if necessary, upward adjustment of the reserve ratio.

Rob,

The simple, and correct, answer is that the Fed didn’t, and still doesn’t, know when it wants it’s cash back.

They also said that someone may have to hold MBS for a very long time to get face value back, and Ben mentioned that he was the only one he new of who had the patience to do it. So in one simple statement, Ben has acknowledged the death of banking as we knew it.(I think that’s what JDH has been hinting at)

Also, I still am pretty sure the Fed bought the $1.4T of MBS that was announced as part of the QE program on the open market. This solves the price discovery problem. I think you are using the term MBS in it’s most generic sense, meaning any kind of mortgage backed security. But the high quality FNMA, 20% down, very good credit(and verified), pass thru MBS did remain liquid in the markets.

It was the bad kind, structured CDOs of subprime loans with the now famous AAA(wink wink) credit rating that all froze up and had an indeterminate price. I think the Fed got their hands on some of those by taking them as collateral on some of their other special programs. I don’t know for sure, but they may have loaned against them at par.

Cedric and MarkS,

Thanks for your responses. Two things:

1) I found some info. about the Fed’s purchases here: http://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/mbs_faq.html

Also, I was under the impression that the Fed’s purchases were for new debt that is being originated so that the mortgage rates will stay low and housing has a chance to recover. If that is so, the majority of their purchases would be newer Fannie/Freddie debt, not the ’04-07 vintages.

2) If an MBS is permanently impaired (people aren’t paying their mortgages and the foreclosed homes aren’t selling for enough to pay the mortgage) I don’t see how holding this stuff to maturity will end up creating profits. Sure, tougher refinancings have probably resulted in much lower prepayment within these MBS but one has to believe that on many of these MBS higher defaults will eventually reach even the top tranches (the AAA ones). Holding to maturity won’t necessarily help there.

Excess reserves are an accounting concept. The physical assets are deposits at the District Reserve Banks. Excess reserves may be used to satisfy reserve requirements. Member banks do not loan out their excess reserves.

Excess reserves are included in “cash assets” on the H.8 Assets & Liabilities of 60 Commercial Banks in the United States. They are also reported separately on the H.3 Aggregate Reserves of Depository Institutions, & on the H 4.1 Factors Effecting (liabilities absorbing), Reserve Balances.

Term-Deposits have several advantages over the current volume of IORs (Dec 30, $1,059,958 trillion) held by the member banks (or the interest paid on their excess reserve balances).

IORs, like Term-Deposits, compete with other short-term, money market instruments, & yields.

The FOMC can calculate and sell whatever volumes, durations, rates of interest, at whatever auction times, or to individual banks (small, medium, & large), & whatever other explicit covenants, it wants to target. I.e., the FED can use a systematic, measured (staggered), technique, to unwind IORs (if necessary).

Term-Deposits will give the “trading desk” all the flexibility it requires to keep the member bank’s required reserves, and the banking system’s excess reserve balances, at the FOMC’s desired level, and at the proper non-inflationary path (as the money supply can never be managed by any attempt to control the cost of credit). Bank reserves (and their lending operations), are principally constrained by bank customer payments/debits, or prudential reserves).

Member banks should initially have the option to convert, or substitute, some proportion of their IORs, into Term-Deposits. A conversion privilege would smooth the transitioning and unpredictable, and vacillating, demand of competing IORs.

Delimiting the volumes should be confined to a percentage of bank capital adequacy ratios (up to 100%), or some percentage of the current volume of IORs now held. The idea is that the provision should not retard the growth of new money and bank credit (as IORs, which caused widespread disintermediation among the non-banks, and shifts in member bank earning assets, essentially retiring commercial-bank owned investments, or acted as decidedly deflationary forces, have done. The volume of IORs has also been mal-distributed, or skewed towards the larger commercial banks).

Term-Deposits have more advanced monetary management characteristics as compared to IORs, which in the long-run, Term-Deposits will replace (The ECB has always been one step ahead of the FED. They require all reserve requirements to be maintained at the Central Bank. I.e., the only type of bank asset that the FED is in a position to constantly monitor, and absolutely control, are inter-bank deposits at the District Reserve Banks owned by the member banks. But the US allows vault cash to be applied to their reserve requirement & the trend of vault cash (& ATM networks), plus retail deposit sweep programs, has outstripped the need for the higher levels, of the past volumes, of legal reserves.

Term-Deposits act exactly like raising reserve ratios (a credit control device, by raising, or lowering, the volume of outstanding legal reserves), as a measure to vary the banks legal lending capacity (increase, or decrease, idle, unused, bank deposits), as opposed to the unpredictable, and surging, demand for IORs (given no change on the asset side of the FEDs balance sheet).

Fixed volumes, for fixed maturities (no early withdrawal privileges), will make Term-Deposits, less volatile, and more predictable. It makes it easier for reverse repurchase agreement transactions (& the FEDs other tools), to complement and balance Term-Deposit purchases, rollover, & runoff.

But, just as increases in IORs were contractionary, decreases in IORs, and/or Term-Deposits, will be on balance, inflationary. I.e., even as the asset side of the FEDs balance sheet (lending facility programs) simultaneously declines, asset substitution will increase the transactions velocity of money (real or financial investment).

I.e., cash will roll-off, the Feds balance sheet will still balance, but the banks portfolios will shift (from lower yielding IORs, to higher yielding financial instruments). I.e., existing money will be activated and exchanged.

Rob,

Thx for the link. That finally answers the open market purchase question(they are), and of what kind of MBS.

“What securities are eligible for purchase under the program?

Only fixed-rate agency MBS securities guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae are eligible assets for the program.”

These are mostly AAA. F&F began a foray into subprime around 04-05, tho I’m not sure if they even tried to securitize these. They do hold some loans on the books, and those were financed thru sale of F&F corporate bonds(the worthless ones).

As far as influencing mortgage rates, new mortgages are priced based on the market rate(composed of old bonds with floating prices/fixed rates or coupon). So the Fed is trying to prop up the entire market to keep rates down on new mortgages.

If default rates go up, you don’t get all your money back, even if you hold to maturity.

Somewhat related:

The long-term costs of bailouts and nationalization of mortgage debt on inflation and external debt

Cedric,

MarkD provided the link–thanks Mark. But thanks for the great commentary, and the great blog.

So now it is very clear, any bust up in Fed-owned MBSs, are guarunteed by FNM/FRE, et.al. With the Treasury now backstopping these entities without a clear cap? (thanks for the xmas eve announcement Treas), the taxpayer is explicitly on the hook for the Fed’s holdings. As the Fed “printed” the $ to buy these MBS, this flavor of QE is backstopped by the taxpayer; that’s rich (pun intended).

Or have I got it wrong?

Rob,

Ya mon, you got the picture.

Plus one of these years the Fed still needs to soak up short term liquidity, to fight any inflation pressures this may someday cause. Or asset bubbles,since they define that as something different from inflation. Or the other thing that is very possible in my mind, thru the wonder of intermediation by international banks and international corporations, the money gets invested in foreign lands. Whoops.

So the Fed will be paying interest to banks, be very conflicted about fighting inflation (the higher inflation gets, the more interest they need to pay), and your tax dollars, and negative real interest rates on your money, will be funding growth in EMs.

I love it when a plan comes together.