By David Papell

Today, we’re fortunate to have David Papell, Professor of Economics at the University of Houston, as a Guest Contributor.

In his speech at the American Economic Association meetings on Monetary Policy and the Housing Bubble, Fed Chair Ben Bernanke argued that, in contrast to the critique by John Taylor, monetary policy was neither too stimulative during 2002-2006 nor caused the housing bubble. In this post, I focus on the first part of his argument.

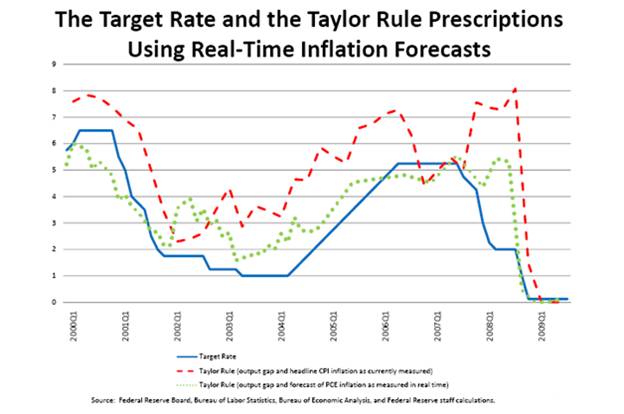

Bernanke’s main point is that, using the Taylor rule as a benchmark, monetary policy during this period was only too stimulative if contemporaneous values of inflation and the output gap, rather than forecast values of the variables, are used for the evaluation. This is shown in the figure below, which reproduces Slide 4 from his speech. The solid line is the target value for the federal funds interest rate. The long-dashed line is the interest rate prescribed by a rule with Taylor’s original coefficients, so that the interest rate equals 1.0 + 1.5 * inflation + 0.5 * output gap, using headline CPI inflation as currently measured. The short-dashed line is the prescribed interest rate using the forecast of core PCE inflation as measured in real time. The gap between the implied Taylor rule interest rate and the actual target for the federal funds rate is much larger with currently measured than with forecasted inflation, leading to the conclusion that, since monetary policy evaluation should be conducted using forecasted inflation, Taylor’s critique is refuted and monetary policy following the 2001 recession appears to have been reasonably appropriate.

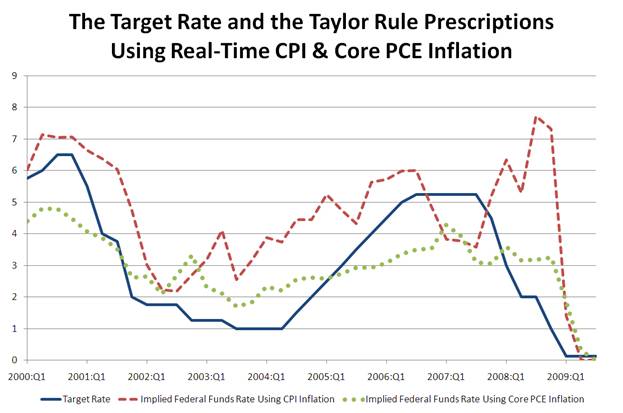

This is an apples-to-oranges comparison. Bernanke is making a contrast between Taylor rule prescriptions with currently observed and forecasted inflation using one inflation measure for the former and another inflation measure for the latter. In order to make an apples-to-apples comparison, the figure below depicts the target federal funds rate, the prescribed federal funds rate using CPI inflation, and the prescribed federal funds rate using core PCE inflation, both measured using real-time data. The gap between the implied Taylor rule interest rate and the actual target for the federal funds rate is much larger with headline CPI than with core PCE inflation. Since neither measure uses inflation forecasts, it is clear that Bernanke’s results depend on using two different measures of inflation, not on using currently observed versus forecasted inflation.

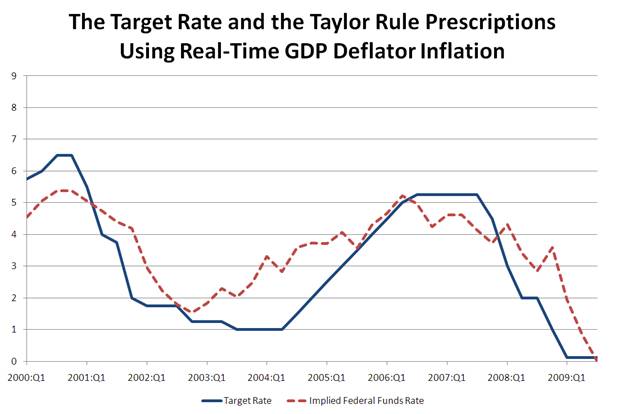

Bernanke’s second point is that proponents of the standard Taylor rule using current inflation values would have recommended that the FOMC raise the policy rate to a range of 7 to 8 percent through the first three quarters of 2008 — a policy decision that would not have received much support among monetary specialists. The reason for this unappealing result is that record-setting oil prices in the first two quarters of 2008 caused headline CPI inflation, but not core PCE inflation, to spike sharply upward, not because the standard Taylor rule doesn’t use forecasted values. Moreover, describing a Taylor rule using CPI inflation as standard is misleading and ignores the fact that the original Taylor rule paper, as well as much subsequent research, uses the GDP deflator as the inflation measure. The figure below depicts the target federal funds rate and the prescribed federal funds rate using real-time GDP deflator inflation. Two points are evident from the three figures. First, the gap between the implied Taylor rule interest rate and the actual target for the federal funds rate is larger for GDP deflator inflation than for core PCE inflation, although smaller than for headline CPI inflation. Second, the Taylor rule prescriptions for 2008 are similar for GDP deflator and core PCE inflation, with both implying much lower interest rates than are implied by the Taylor rule using CPI inflation.

In his speech, Bernanke ascribed two results — that Fed policy was too stimulative following the 2001 recession and that the policy rate should have been between 7 and 8 percent in the first three quarters of 2008 — to the use of a “standard” Taylor rule with contemporaneous, rather than forecasted, inflation. In fact, both results come from using headline CPI versus core PCE inflation– not from using contemporaneous versus forecasted inflation. In addition, Taylor’s original paper used contemporaneous GDP deflator inflation. With that measure, Fed policy was still too stimulative during 2003-2005, but the implied policy rate in the first three quarters of 2008 was between 3 and 4 percent, not between 7 and 8 percent.

This post written by David Papell.

The FED wasn’t to stimulative because there was nothing to stimulate, it was why bond prices stubbornly refused to rise much either.

When you are in disinvestment, you are in dis-inflation tumbling towards deflation. It is why the MNC’s like it. They can max profits without spending alot investment in the host country further maxing profits.

The RE bubble was going to happen no matter what. The money that poored from the 90’s boom had to go somewhere and RE was considered a safe investment. All the Taylor rule would have done is force a double dip recession and spread the RE boom out longer.

The problems are structural and international. Things like financial,medical,military industrial complexes are on the big stage for your amusement through borrowing to keep the illusion of a economy.

My advice for the MNC’s is to start giving back to their host countries or face their own destruction.

The evidence makes it quite clear that the Fed was too stimulative during 2003-2005, but the question not discussed here is why that was done.

A careful look at the graphs makes it clear that interest rates were kept low until the 2004 election, then spiked.

The decision to keep interest rates low, frothing the economy, for the 2004 elections should raise questions about whether the Fed acted in its proper independent role at that time or chose to act politically to influence the 2004 election.

The Fed went too low in 2002, and then went too high in 2006. Oversteering like a drunk driver going from curb to curb.

At the time I felt they should stay near 3% lest they should fuel a bubble with the lower rates, and then crush the economy with the following higher rates. I feel even stronger about that now. Why can’t they use a steady hand on the wheel?

Shall we discard money supply as a potential erring factor of the Central banks ?

Whilst professor Taylor is raising Central Banking to the rank of a nano science,Marshall was dealing with the heavy smelters of Central Banking.

Few figures hereafter may show putative children looking for foster parents:

Debt to GDP (worldwide)

Money supply

http://www.shadowstats.com/article/money-supply

Thomas Fillipon table 1 P33 on evolution of the share of Non financial

corporate credit over GDP

http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~tphilipp/papers/finsize.pdf

The role of reserve requirement P 77

http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/10/01/Thornton.pdf

Bernanke is falling back to taylor rule (like the dual mandate) as the old inflation only targetting he preached was discredited. But Taylor rule discredited also in the crisis. “he” massively rejected it in 3Q. 2007 with real GDP growing over 3% and inflation rising, he was rapidly cutting, because the banking system had a heart attack in Aug and was freezing up. thank goodness he did.

I like the taylor rule in some ways for explaining bahavior and for guidance. but if we dont admit we will again massively ease in a crisis, and think about earlier restraining credit without Taylor signals in a credit bubble, we will just do another version of this in less than a decade.

Greenspan:Bush::Burns:Nixon.

In general, the Fed follows a rule of lax monetary policy preceeding presidential elections in which Republicans are incumbents. I believe this a standard result from workhorse DSGE models. You should have seen the Bank of England under Thatcher.

Great post, a very clear explanation.

Very nice post. John Taylor also has an opinion piece on yesterday’s WSJ that touched the data issue as well.

I also want to point out that it was not news that there are huge error bands around inflation and growth forecasts, and it was not news that there are typically big revisions to current releases. In fact, the FOMC were consistently overforecast inflation and underforecast GDP growth in the late 1990s. The fact that it is difficult to forecast inflation and growth should lead the Fed to put some restraints on their policy actions. After all, very low fed funds rate is distortionary — so if one cannot pin down the proper policy rate or the time lags of policy impact, one should not try to distort the market too much. instead, they went overboard. That is why I think arrogance is partly to blame.

When the longer-term rates didn’t follow the extraordinarily low fed funds rate, instead of viewing that as a vote by investors that policy rate was too low, Bernanke was frustrated so he made the FOMC promise to keep the fed funds rate at 1% for “considerable time” to get the longer-term rates to come down. It took the FOMC 3 or 4 meetings just to get rid of that phrase before they could actually raise the rate, which is another reason that the policy was too easy for too long during that period.

Surprisingly good article.

There seem to be one of two conclusions to draw from the paper. Either Time’s Man of the Year is stupid or he is a liar. I don’t think he is stupid.

Zephyr makes an astute comment with “Oversteering like a drunk driver”. If the Fed follows Bernanke’s recommendation of plugging forecasted inflation into the Taylor Rule, he will virtually guarantee such “drunk driving”.

Substituting a forecasted inflation rate into the Taylor Rule would destabilize the system. Forecasts tend to extrapolate the recent past into the future. If the underlying behavior (inflation) is anything but constant, the forecast will likely overshoot (or undershoot) the actual behavior during transitionary times. Hence, using forecasted inflation in the Taylor rule will tend to amplify swings in inflation rather than dampen them out: “oversteering”.

This is a fundamental principle of complex feedback systems which our economy is one of (see Forrester, “Industrial Dynamics”, Productivity Press, 1961, p 349 — amplification from forecasts). A simple rule based on some sort of averaging of recent history, like the standard Taylor Rule, would do much better in dampening swings in inflation than the one proposed by Dr. Bernanke.

David Papell, thanks for an interesting post. So why do you think Bernanke makes the apple-to-oranges comparison rather than the apple-to-apple comparison you lay out above?

“The evidence makes it quite clear that the Fed was too stimulative during 2003-2005, but the question not discussed here is why that was done.”

This raises a great point and one that summarizes the real issue for me. I think the drunk driver had his foot on the ‘rate’ pedal too long because; the asset reflation necessary to replenish government coffers was limited to the FIRE (Finance/Insurance/Real estate) economy rather then industrial. Remember we spent the prior 25 years shipping our manufacturing and middle class over to China. Regulatory capture, ha! Try State Capture!

David Papell states:

Moreover, describing a Taylor rule using CPI inflation as standard is misleading and ignores the fact that the original Taylor rule paper, as well as much subsequent research, uses the GDP deflator as the inflation measure.

However, according to John Taylor’s 2007 Jackson Hole paper:

Observe that the actual and the alternative paths depart in the second quarter of 2002 and merge again in the third quarter of 2006. I emphasize that this is only one of many ways to carry out such a counterfactual exercise. Here I use the CPI as the measure of inflation and assume response coefficients of 1.5 and .5 on inflation and real GDP, respectively.

This is the paper where Taylor argues that the housing bubble was due to lax monetary policy over the period 2003 through 2005. James Hamilton, in an earlier entry on this blog, provides a brief summary of Taylor’s 2007 Jackson Hole paper.

The Zephyr’s comment is spot on. By overreacting to the consequences of previous overreaction, the Fed is the main source of economic instability. That’s the essence of Milton Friedman’s critique of the Fed.

Yes, indeed. Why the controversially low overnight rates for so long?

For the presidential election?

An over-reaction that was part of the hyper-vigilant mass hysteria following the Sept. 11 box-cutter attacks?

Guns and butter a la early 21st century? American citizens wanted 4,000 square feet homes and 3/4 tonne SUVs as the obesity epidemic soars. People from New Jersey wanted to move into condominiums with a view in the West Bank. (Violent colonialism and making the desert bloom ain’t cheap even if G-d ordains it.)

A domestic subsidy to the US financial export sector?

A desperate attempt to keep the US dollar low to aid the shrinking manufacturing sector?

Bernanke’s way of conveniently adapting popular theories to fit his desired message is typical among politicians.

I’ve never done the analysis, but even though it seems obvious, is there actually a proven causal link between central bank target rates and the occurrence of bubbles? Everyone out there seems to assume this, as it seems to pervade the collective “common sense.”

Maybe common sense is broken. Japan had near 0% rates for a decade and no bubble came out of it (except Japanese government bonds and yen themselves?)

In 2004-2007, there was no reason investors had to go out onto a relatively flat yield curve and buy crappy long duration debt. The central banks only targeted the front end. As evidenced now, interests rates (at least in the range of 0%-5%) have little to do with the marginal willingness to lend (which drives the money multiplier up). The idea that you will get your money back as a lender is what I believe more substantially effects that.

And in 2004-2007, the belief pervaded that if you bought debt, you would get your money back, because the fundamental investment was safe.

Economists like to have complex arguments about one detail. But perhaps they are missing the big picture.