What message should we take from negative real interest rates?

If you’re worried about inflation, one investment you might consider is an inflation protected security from the U.S. Treasury, such as the 4-1/2 year TIPS just issued. For a $1,000 investment, the Treasury will make a $2.50 coupon payment to you twice a year (or a 0.5% annual rate), and give you your $1,000 back in April 2015. If the headline CPI goes up between now and then, both the coupon and principal will go up by exactly the amount of inflation. And if there is deflation, you still get the $2.50 coupon and $1,000 principal back without penalty.

Doesn’t sound like much? Well, it looked good enough to investors that they just bought $10 billion worth of that security, paying $1,050 for each $1,000 par value. At that price, if there’s no inflation, they lent more to the government than they’re ever going to get back in coupons and principal over the entire life of the bond. That works out to a negative yield to maturity on the bond of about -0.5% if there’s no inflation over the next 5 years.

|

But what else are you going to do? You could buy a 5-year note without inflation protection offering a nominal yield of 1.2% per year. But if you expect, say, 2% inflation per year over the next 5 years, in real terms you’d lose even more money on the nominal security than you would on the TIPS.

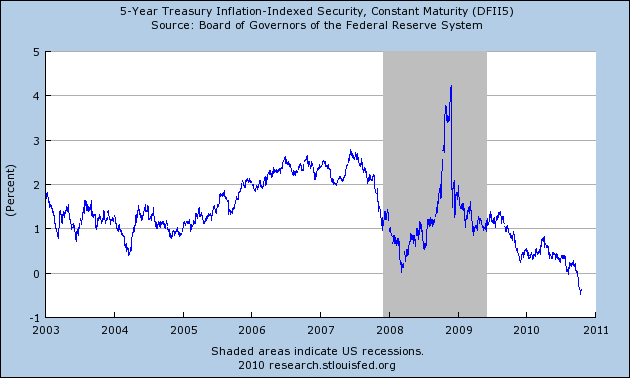

Although this appears to be the first time that newly issued TIPS have locked in a negative real return, that’s because TIPS have only been offered to U.S. investors since 1997. You can get a longer time series by comparing the yield on a 6-month T-bill at any date with what the CPI inflation rate actually turned out to be over the subsequent 6 months for which investors held that bill, a magnitude sometimes described as the “ex-post real interest rate.” That series is plotted below. We’ve actually been in a period for several years in which short-term loans to the government were a losing proposition in real terms, and the longer-term real yields such as the 5-year TIPS are only now coming down to join them. The recent era of negative real yields was briefly (if spectacularly) interrupted in the fall of 2008, when a sharp deflation in the CPI made short-term loans to the government an excellent deal for the lender in ex-post real terms.

|

Negative ex-post real rates on short-term securities are thus nothing new. We saw them for much of this decade and for much of the 1970s. Although negative realized ex-post real rates do not establish that investors knew that they were in for a losing bargain in real terms, they persisted long enough in the 1970s that it’s hard to believe that people were shocked by the continually repeated outcome. I think if TIPS had been offered at that time, we would have seen a negative real yield then, too.

What does a negative real rate signify? If you consider a simple one-good economy in which the output is costlessly storable, a negative real rate could never happen– people would simply hoard the good rather than buy such miserable assets. You’re better off storing a can of tuna for a year than messing with T-bills at the moment. But there’s only so much tuna you can use, and many expenditures you might want to save for can’t really be stored in your closet for the next year. It’s perfectly plausible from the point of view of more realistic economic models that we could see negative real interest rates, at least for a while.

Even so, within those models, there’s an incentive to buy and hold those goods that are storable. And in terms of the historical experience, episodes of negative real interest rates have usually been associated with rapidly rising commodity prices.

|

In terms of the Fed’s policy objectives at the moment, one of the problems with deflation is that it guarantees a positive real return just from stuffing cash under your mattress. A primary purpose of the Fed’s contemplated QE2 is to prevent this and spur consumers and firms to invest funds productively rather than hoard cash. Insofar as the recent moves in TIPS and other yields represent the market already pricing in the Fed’s next steps, one might conclude from the latest TIPS readings that this aspect of the Fed’s strategy is already working.

And that makes it a good time to bring up again the point that we should not expect too much from QE2. The Fed can help, but it’s not going to solve all our problems. I earlier guessed that the market has already priced in another trillion dollars in long-term asset purchases by the Fed. I recommend that the Fed go through with that, but keep a watchful eye on real rates and commodity prices before attempting any more than that.

“In terms of the Fed’s policy objectives at the moment, one of the problems with deflation is that it guarantees a positive real return just from stuffing cash under your mattress. A primary purpose of the Fed’s contemplated QE2 is to prevent this and spur consumers and firms to invest funds productively rather than hoard cash.”

So why not create more cash (currency) instead of demand deposits created from debt to increase the amount of medium of exchange?

From the charts above, we seem to have experienced negative post-facto real yields for much of the past decade. A cornerstone of stimulus thinking is that the economy, with a little “push”, will naturally return to “trend growth”. Only we seem to have been “pushing” for a quite a while now…

Rising commodity prices? Like oil shocks.

There’s a view in the energy community that 2008 was about an oil shock. See Jeff Rubin’s defense of the argument here: http://www.aspousa.org/

Governments,banks,central banks are coming in competition with the savers in the interest rates markets.

Risks (solvency,liquidity,inflation) and prices are given as constant.

ECB October, monthly bulletin is providing for a comprehensive review of the monetary condition in Eurozone

Money funds are directed to the lesser of the risks ie goverment bonds avoiding the monetary financial institutions (chart D ECB P24).

M3 and loans are negatively sloped (P22)

Direct investments are negative P57 Chart 38 (may be a function of return on investment and prices?)

PS As an aside the write off loans to household and non financial institutions are completely inconsistent with the debt amounts outstanding P96

Implications:The risks pricing are much too generous,banks ,financial corporations may have advantage in the assets prices distortion but for book keeping only.

Whilst not updated, the Fed indicators on direct investment were not showing much of an inflexion point P15 as of Q2 2010

http://research.stlouisfed.org/economy/indicators/summary.pdf

Liquidities are available,risks as well, pricing are not commensurate with return.As mentioned before, the financial interest rates components are quiet neutral in the debt servicing of mature companies (around 5 % of revenues). When in excess, this is leverage and therefore solvency where liquidities may keep stability until they do not.

Interest levels are more of importance for small corporations and start up (no data are made available)

Nice blog post, Prof Hamilton.

Negative real interest rates should also be positive for equities.

Using a Gordon growth model with dy+g=erp+rby where dy is dividend yield, g is dividend growth, rby = real bond yield and erp is the equity risk premium, negative rby pushes up erp (ceteris paribus).

Even if you think the erp is not as high as you may want, it is difficult to argue that you are paid for taking the risk for investing in bonds. This assumes deflation doesn’t occur because that would lower g.

Take S&P. dy is around 2.0%. Assume g = 2.5% (US sustainable growth rate – and this may be low). Take rby for 5 years at -0.5%. erp then is 5%. Not bad by historical standards.

Wouldn’t it be a lot easier if we let the markets determine interest rates? Meaning, the Fed no longer manipulates rates in any way. Is it a fair statement that the markets are infinitely better at determining rates than the FOMC? Why do 98% of economists today argue constantly about what the Fed should do with rates, instead of debating whether it should continue to be controlled? The same, predominant economic theory that continues to make suggestions on what needs to be done, is the same theory that put us in this position. I look forward to everyone’s reply.

Storage is tied not only to interest rates, but also to anticipated future changes in prices and the costs of storage. If people start to hoard commodities then current prices will go up, causing the expected price change between the present and the future to go down. Also, as hoarding increases, marginal costs of storage likely increase.

My point here is that it’s hard for me to see large-scale hoarding even in an environment with negative real interest rates. Hoarding can only happen if markets irrationally believe that price increases will be sustained indefinitely–i.e., a speculative bubble. Hopefully markets will be wary of such things after recent experience in housing and stock market prices.

Besides, when has a speculative bubble occurred with commodities? I know price spikes have occurred when some have tried to corner certain markets, but I think that’s different. We’ve also had price spike when inventories were depleted, there was real worry of impending supply shocks, or trade policies interfered with international commodity trading. But these are all very different stories as well.

Even if your worry is an important one, I would suggest that the Fed keep its eye on *inventories* not prices. Prices may increase if demand increases, which would be a positive sign of recovery, not necessarily hoarding.

“What does a negative real rate signify?”, he asks.

There you go again, JDH, responding with a nonsensical strawman case of a single good economy (canned tuna! give me a break) and not shedding any light or doing any useful teaching on the subject.

So what does it mean? It means that a large number of well informed, professional fund investors whose job it is to bet on outcomes, are willing to bet their success that the US is in deflation (net of oil, which is not a stable situation) and it will continue over their multi-year investing horizon. Hence, they are taking action, and acting more quickly than Bernanke has been able to act. It also means that most of the economic and monetary policies enacted over the past 3 or 4 years have been ineffective.

Time to start thinking some new thoughts?

Albatross Avenger: I’ve been claiming that the Fed’s main choice is what the inflation rate should be, and that some choices are better than others. The rate of inflation is a summary of what happens to the value of Federal Reserve notes. I do not agree that the value of Federal Reserve notes can or should be determined by the private sector alone. Instead, the value of Federal Reserve notes is very much related to the quantity of Federal Reserve notes that the Federal Reserve allows to be created.

Michael Roberts: No one is talking about either hyperinflation or bubbles. Tuna fish is a better investment than TIPS when the dollar price of a can of tuna is held constant, that is, when the inflation rate is 0.0. If you use $1 to buy a can of tuna fish today, you will still have a can of tuna fish next year. If you use $1 to buy a TIPS today yielding -0.5%, you will only be able to afford 0.995 of a can of tuna next year. And for tuna to be a better investment than a nominal 1.2% bond, all that’s necessary is that the price of tuna goes up by more than 1.2%.

Mike Laird: If they expect deflation, your well informed, professional fund investors would not want to buy a TIPS with a -0.5% yield. They would instead prefer to buy a nominal bond yielding 1.2%. They would want to buy the TIPS if they’re expecting more than 1.7% inflation.

I have another question – why does the market pay you to take out a loan in DOW equities (i.e. hold DOW futures), at the rate of about $500 per quarter per contract?

Did we experience sustained negative real interest rates before we had a Fed to manipulate rates?

[not to imply that when we were on the gold standard we were free of gov’t intervention]

Intuitively, negative real interest rates seem unnatural in the absence of a central bank buying debt with mouse-click money.

I suspect that the fed will manage to attain inflation in everything but wages. That should pretty much finish off what remains of the middle class…

Dow question: Don’t know the Dow future fair value specifically, but have you counted dividends? If the dividend yield is larger than the interest rate, the future should be trading less than the index.

‘Marriner Eccles (as quoted in Robert Reich’s ‘Aftershock’): ‘As mass production has to be accompanied by mass consumption, mass consumption, in turn, implies a distribution of wealth — not of existing wealth, but of wealth as it is currently produced — to provide men with buying power equal to the amount of goods and services offered by the nation’s economic machinery. Instead of achieving that kind of distribution, a giant suction pump had by 1929-30 drawn into a few hands an increasing portion of currently produced wealth. This served them as capital accumulations. But by taking purchasing power out of the hands of mass consumers, the savers denied to themselves the kind of effective demand for their products that would justify a reinvestment of their capital accumulations in new plants. In consequence, as in a poker game where the chips were concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, the other fellows could stay in the game only by borrowing. When their credit ran out, the game stopped.’

Naive question of an European observer to esteemed economists and posters: Are there any relevant disadvantages of Mr. Bernanke starting his helicopter and distributing an equal dollar amount to every American (opting-out should be possible and acclaimed), large enough to close the output gap and achieve his target inflation rate?

The American trickle-up poker game could go on, and you would have arguably a fair and efficient solution for the current crisis.

What is the definition of hoarding? Is a Copper Physical Trust existing for the sole purpose of issuing trust investment units and warehousing copper hoarding or an investment?

See JPM prelim prospectus: http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1503754/000119312510234452/ds1.htm#rom111347_4

JDH said “Instead, the value of Federal Reserve notes is very much related to the quantity of Federal Reserve notes that the Federal Reserve allows to be created.”

JDH,

Do you have any historical data to back this claim? I have seen charts of money aggregates that show no relationship between inflation/currency value and money supplies. But maybe the creator of those charts skewed the data for their (political) purpose.

gerold: First, that’s a fiscal proposal, not within the Fed’s scope. Congress could direct Treasury to do that. And some previous rounds of “stimulus checks” have resembled that, generally in the form of a retroactive one-time tax break (so only people with some minimum tax liability got them, but still widely distributed). I’d like to see it implemented as a “payroll tax holiday”, as payroll taxes are even more universally paid (people whose income is sufficiently low don’t pay income taxes, but everyone who works pays payroll taxes).

Second, there are questions about how effective it would be, or at least how quickly it would be effective. People want to save right now, to spend less than they earn. To the extent that they just parked that bonus money in the bank, or used it to pay down debt, it wouldn’t create new aggregate demand. And to the extent that any new spending was on imports, the increased demand would “leak”, supporting employment overseas but not in America. Arguably, by improving household balance sheets, they would become more comfortable more willing to increase their spending and/or start to take on debt again, eventually.

Third, as I said that would take an act of Congress, and our political system is so dysfunctional right now that there’s no chance of fiscal policy on anything like the needed scale (trillions). Instead of having the govt dis-save by the amount needed to meet people’s desire to save, we’re going to force households into dis-saving by destroying their income (involuntary unemployment). We’re going to be stuck with a very long recession and a lot of permanent damage, while politicians keep talking about the deficit as if it’s too large.

Fourth, I agree with your overall point, that the fundamental driver has been rising income/wealth disparity. Without broadly rising incomes, rising demand was only supported by rising private debt. That couldn’t go on forever. And now we’re poised to elect the party whose platform, such as it is, is to concentrate wealth even further and/or shut down the government. Sigh.

markg: Here’s some of the evidence you ask for.

The fly in the ointment is that the days of buy and hold bond investing are over.

Fund managers/speculators are buying tips because they expect the price to rise, simple as that. They could care care less about the yield to maturity because they won’t hold them to maturity.

Negative real rates on goverment securities represent an increase in demand from the expectation that (1) QE2 will not work, (2) interest rates will fall further and bond prices will rise and (3) they are a safe haven, given (1) and (2).

No sane fund manager/speculator is buying tips or any other fixed income security as a buy and hold, if they expect inflation and interest rates to rise in the near future.

JDH:

JDH – “I’ve been claiming that the Fed’s main choice is what the inflation rate should be, and that some choices are better than others.”

– Thank you for confirming that you are indeed part of my described 98%. If inflation is above or lower than the inflation target, they will have to manipulate rates (sell debt/buy debt); so what’s the difference? ‘Inflation targeting’ (2010’s central banking buzz theory), which seems to me no different than ‘Price fixing’ will fail in practice, just like every other policy target used in past. Which choices are better than the others, are you referring policy targets? I would like to know more about what the ‘correct’ inflation target should be; 2%, 3%, 10%, -1%? I look forward to hearing that response.

JDH – “The rate of inflation is a summary of what happens to the value of Federal Reserve notes.”

– Inflation, defined by myself, is what occurs when Brian Sack and 33 Liberty buys Treasury bonds with electronic credits recently entered by someone’s hasty keystrokes. Rate of Inflation could also be defined as a summary of the rate and speed in which the FOMC destroys my savings and purchasing power.

JDH – “I do not agree that the value of Federal Reserve notes can or should be determined by the private sector alone.”

– Why not, Why not, Why not? Are you saying that the FOMC (12 people) can better assign value to money/rates/prices than the collective, autonomous, value discovering public (millions of people)? Why does the market need help establishing value from an institution (The Fed) that has failed repeatedly, over and over, with establishing value. I wonder what a chart of the dollar’s purchasing power since 1913 looks like…..

JDH – “Instead, the value of Federal Reserve notes is very much related to the quantity of Federal Reserve notes that the Federal Reserve allows to be created.”

– I understand this comment, but not how it describes why the private sector cannot value its own money, its future value, price of goods. I would like to know, at what point, and of what cause, would the Economics profession conclude that economic planning is more damaging than any results obtained from it.

Thanks for the link JDH. The first graph is convincing, but since the period covers 1960-1990 some of the data includes gold standard era and some post gold standard. So it is hard to evaluate. I thought the Fed stopped tracking monetary aggregates because they said the data was not conclusive enough to establish any correlation between money supply and inflation. The recent explosion in base money with no inflation would lead me to believe money supply and inflation are not related.

Mike Laird claims that professional investors are betting on deflation. That seems a fairly naive reading of what they are doing. For starters, TIPS protect against inflation, so if investors are paying up for TIPS, they are protecting themselves against inflation, not deflation.

Professional investors hold portfolios of assets. The point to holding a variety of assets which perform in different ways is to insulate capital and returns against a variety of possible outcomes, in order to produce the best mix of risk and return. Investors holding a mix of investments appropriate to a certain median expectation of future outcomes would, in the face of changed circumstances, buy assets that adjust the portfolio to the implication of those circumstances. The purchase of TIPS is not a response to sudden change in the overall outlook. It is an adjustment at the margin to a shift in risk. Since it is happening soon after the Fed signaled more easing, the changed set of circumstances looks to be a somewhat greater risk of moderate inflation than had earlier been the case. As I understand it, the 5-year TIPS, as priced, implied a 1.56% CPI rate over the maturity of the issue.

Interesting how Mr. Laird can claim that our host is missing the point in the same comment that Mr. Laird so utterly misses the point.

“Albatross Avenger: I’ve been claiming that the Fed’s main choice is what the inflation rate should be, and that some choices are better than others. The rate of inflation is a summary of what happens to the value of Federal Reserve notes. I do not agree that the value of Federal Reserve notes can or should be determined by the private sector alone. Instead, the value of Federal Reserve notes is very much related to the quantity of Federal Reserve notes that the Federal Reserve allows to be created.”

By federal reserve note, do you mean currency, the demand deposits created from debt, or both?

lilnev: thx for trying to answer my question which was primarily an economic one, and wrapped in a distributive justice and effectiveness context.

Bypassing the legal question which was discussed here on Paul Krugman’s blog and and on which you seem to be largely right: wouldn’t it be very efficient to create a little wealth for everyone as proposed, thereby – by definition – closing the output gap, providing full employment, creating inflation expectations, improving balance sheets of households, allowing for some loan repayments, etc. ?

Would USD 3,000 per person and year be enough to save the economy in such a straightforward way (may be an economist could help with a rough estimation)?

If yes, why shouldn’t that be done? Where are the major disadvantages (clearly some additional imports from China is not one of them)? Why is this option only occasionally mentioned, but never seriously discussed as a realistic solution proposal?

The US people would even work for the not so ‘free’ lunch, as they become employed again.

The negative rate on TIPS is what I would expect given current circumstances. If you hold cash or very short-term notes and roll them over for the next five years, and if you expect economic conditions to stay pretty much as bad as they are, and the Fed to keep the short term rate essentially at zero, you will expect to get roughly a zero nominal return, with no inflation protection. If you don’t discount entirely the possibility that the Fed may actually succeed in generating positive inflation (or even the possibility that they will do something downright stupid), then inflation portection is worth something to you, and you should be willing to accept a negative rate on TIPS.

a, thanks. I thought of that, and I agree that must be it. Basically, assuming arbitrage between holding futures and actual equities, the condition would be

(A) (appreciation) + (D) (dividends) – (TE) (the transaction costs on buying and selling equties)

=

(A) (appreciation) + (I) interest – (TF) (the transactions costs on buying and selling futures contracts).

The A’s cancel, leaving dividends versus interest and the difference in transactions costs (which are negligible for the futures contracts). The roll-over cost from holding a future DOW “buy” order has gone from about $160 per contract per year before the recent crisis to about -$240 per contract per year, or a net reduction of about 4% of the contract value. That would roughly jibe with the change in short-term interest rates.

But why is the arbitrage against the DOW equities? Why isn’t it against the cost of borrowing to fund about 95% of the futures contract, in which case only the interest rate would matter (transaction costs would be negligible on futures contracts and short-term debt instruments)?

A late reply to your response to my comment (thanks for that, by they way):

Wouldn’t you expect there to be diminishing marginal utility of tuna? That is, at some point I won’t want to store more tuna because I’m really hungry right now, plus I’ve got so much stored that I will be more than capable of satisfying my hunger tomorrow.

Put another way, in aggregate there is a demand curve out there, and that matters. Quite a lot, I would think. In the range between +/- 1 percent real rate of return, demand (or relative price expectations) seems the larger issue than interest rates.

The empirical link between real interest rates and commodity price changes is interesting and seems strong. I recall a paper by Heal showing this way back. It makes sense. But it seems to me there are limits, and I don’t see why it’s a big concern.

Also, the most striking correlations seem to appear in the 70s and 80s when either real or fear of middle east oil supply disruptions had big commodity price effects–something you know better than perhaps anyone.

Is it not possible that cause and effect are reversed? Commodity price shocks affected inflation (perhaps unexpectedly) and this affected real interest rates? If it were a hoarding story it should show up in inventories, no?

Hi Professor,

That was a great article. I am a gold trader and I hear a lot of talk about how gold tends to rally when the real interest rate goes negative (or is anticipated to go negative). The question I have pertains to how to chart the real interest rate in between monthly inflation reports. Is there a particular yield that has the inflation expectation priced in so that you can see how investors are anticipating upcoming inflation? In this way, when the yield drops below zero, you can understand what the market is pricing in? Thanks,

Shawn Cooke

Shawn Cooke: You can see a daily plot of the 5-year real rate here.