Professor Mulligan asserts that the payroll tax cut will have little effect on output, even in sticky price Keynesian, and New Keynesian, models. He writes:

Sticky-price Keynesians agree that an employer tax cut would have the same effect as an employee tax cut. But both cuts have a minimal employment effect, if any, because it’s not employer costs that hold back hiring — it’s the lack of demand for consumer goods that would be there if only prices would fall.

Indeed, some sticky-price Keynesians have argued that payroll tax cuts would actually reduce national employment, because more people would compete for jobs that aren’t there.

In summary, the proposed payroll tax cut does not increase national employment in the sticky-price Keynesian model, regardless of whether the cut is aimed at employers or employees. The sticky-wage Keynesian model says that, because the cut is aimed at employees, it will not increase hiring in those sectors where wages are sticky — such as the market for low-skilled workers.

It is interesting that Professor Mulligan observes that sticky-price Keynesians believe in demand effects arising from payroll tax reductions, then quickly segues to Krugman’s model, and finally completely fails to deal with the demand argument, and focuses on the supply side. In this sense, Professor Mulligan remains completely predictable and consistent (see here, here and here).

Professor Mulligan argues that the reduction in taxes will not affect the labor supply response in the sectors with sticky wages, exactly where least adjustment is necessary. But even if employment does not increase, the total after-tax wage payments going to workers will go up, raising disposable income, and hence increasing consumption via the standard Keynesian consumption function.

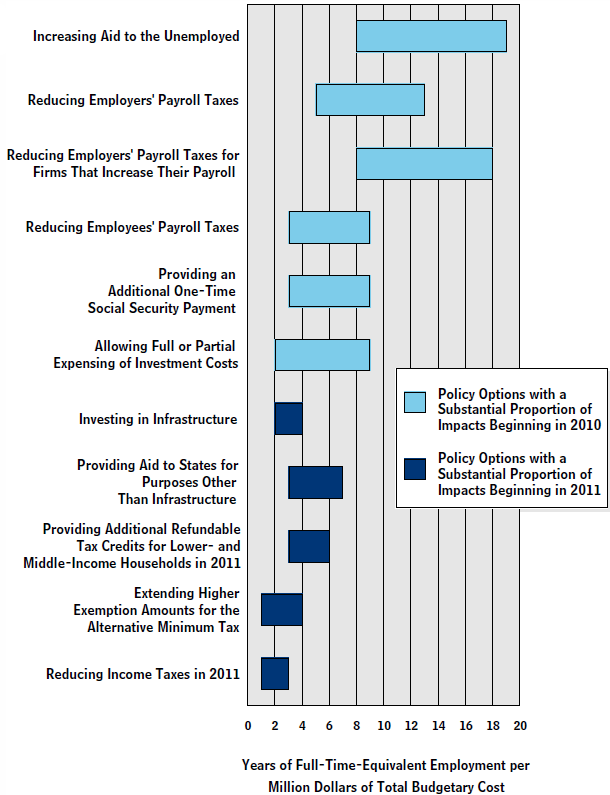

The CBO has assessed the per-dollar effect of payroll tax reductions on employment. Focusing on this demand side, rather than supply side, it compares well with other measures.

Figure 2 from CBO Director D. Elmendorf, Policies for Increasing Economic Growth and Employment in the Short Term February 23, 2010.

The payroll tax reduction is therefore a farily effective means of stimulating the economy, assessed from the demand side, relative to tax cut extensions (note higher yielding measures, such as payroll tax reductions for firms that increase employment [1], were killed off by Republican opposition).

By the way, the CBO has tabulated the components of the tax deal. The two year cost is $797 billion, while the ten year cost (2011-2020) is $857.8 billion. Macroeconomic Advisers has provided an interesting breakdown of the components. I’ve shaded the components primarily favored by the Republicans pink, and those primarily favored by Democrats blue (keeping the AMT fix uncolored).

Figure 1 from Table 1 of The Tax Compromise: It’s Complicated, Macroeconomic Advisers, Dec. 8, 2010. High income tax cuts relates to extension of EGTRRA/JGTRRA provisions to households with income in excess of $250K (aka Todd Henderson households).

In other words, most of the package is not in line with Republican wishes; on the other hand, the “high income tax cuts” as well as estate tax reductions do provide extremely high benefits to a very small portion of the overall economy, with (as stressed in Figure 2 from CBO) very little stimulative impact on the economy. In this sense, these provisions constitute almost pure rent transfers.

More on the advisability of continuing tax cuts for high income households here, on the revision of the macro outlook here and here.

Instead of trying to predict the future, Mulligan should spend his time explaining why the Bush tax cuts had little effect on output.

Keeping more of what I earn, rather that giving it to “great society” programs is great, regardless of what the Keynesian models say.

Wes Keeping more of what I earn

We’d all like to keep more of what we earn. That’s not the point. The issue is that we would also like to earn more, not just keep more of what we earn. If you’re income goes to zero because you’re involuntarily unemployed due to the recession, then keeping 100 percent of zero is small consolation. I’d rather pay a little more in taxes if it significantly improves prospects for earning more.

Menzie Krugman is right. This is more evidence of macro in the Dark Ages in which many economists seem completely oblivious to lessons learned in another age. Diehard RBC types like Mulligan don’t even properly understand Keynesian models, which is why their criticisms of Keynesian models always seem so odd. This is what happens when you try to practice economics with one curve tied behind your back.

Menzie: Perhaps the ‘Middle Income Tax Cut,’ along with the ‘AMT Fix,’ should also be uncolored in your graph?

Menzie,

Why do you continue to give the CBO any credibility? In 1998, the CBO report “Long Term Budgetary Pressures and Policy Options” predicted the debt/gdp ratio would continue to drop and reach 17% by 2020.

The Bush tax cuts (2001 and 2003) did nothing but fuel speculative bubbles. The wealthy did not invest in new production because they could not sell current output let alone additional output. So they bid up existing asset prices with their money. On the other hand, the 2nd qtr 2008 Bush tax rebates showed a spike in gdp. A tax rebate is just an after the fact tax cut.

If tax cuts go to the demand side where they are spent, that spending is someones income who will pay a tax on that income. If the tax cuts go to someone who will save the money, the govt will collect no tax. So the budget outcome is more determined by the privates sectors desire (or ability) to save or spend. I do not know if the CBO takes this into consideration when making predictions on the effects tax cuts on the deficit, but given their track record, I doubt it.

“Indeed, some sticky-price Keynesians have argued that payroll tax cuts would actually reduce national employment, because more people would compete for jobs that aren’t there.” Whaaaa? I believe he means “would actually increase the unemployment rate” , not “reduce national employment” and that doesn’t require Keynesian analysis. In addition, in any model that doesn’t just impose a wage level and say “sticky”, fundamentals do work over time. More people looking for work lower the reservation wage – stickiness just means the reservation wage falls slowly. I’d be happy to be corrected on any of this, but only if the correction is correct.

Mulligan using a Keynesian model seems a bit like an attempt at “verbal judo”, but Mulligan turns out to be a white belt.

Menzie-

Your citation of the CBO results raises three questions:

How good is CBO’s track record – have their predictions been accurate?

Is Keynesian theory correct? I realize this may seem like heresy to you, but I am rereading the General Theory right now, and aside from the bad and confusing style, I wonder if it is all just a con job.

Are the CBO models, including the code and instructions, available to the taxpayer?

markg CBO is not in the business of making unconditional forecasts. All of their forecasts are conditioned on current law. The models that CBO uses are not all that different from other macro models used by other government entities (e.g., CEA, Federal Reserve, Treasury) as well as private and academic economists. CBO does not ordinarily make dynamic forecasts, but as it turns out (properly done) dynamic scoring techniques don’t really make a helluva lot of difference to the bottom line. And the marginal benefits of dynamic scoring are probably outweighed by the added risk of politically manipulated scorings. A good example of that kind of risk can be seen in Rep. Paul Ryan’s intellectually dishonest “Roadmap” that he sent to CBO along with a laundry list of things to not count in the CBO analysis.

Menzie engages in the typical mercantilist slight of hand. His base line is what will be if the government allows bad policy to raise taxes and engage in Keynesian pump priming.

If we take today as our base line the bar graph looks totally different.

-The “high income tax cut” becomes a high income tax increase.

-The estate tax rather than declining from 55% to 35% will actually rise from 0% to 35%.

-Accelerated depreciation will simply shift future business cost to current years allowing income to be shifted to later years meaning the only net change will be the cost of money on the accelerated expense.

-The AMT cost is actually preventing some of the taxpayers not paying the AMT from having to pay it in the future so this is actually preventing a tax increase.

-The payroll tax cut will reduce the amount paid currently but this tax is theoretically paying for Social Security and the costs of that will not change. The effect of this change will actually accelerate the insolvency of Social Security. This is actually monetarist pump priming or Keynesian welfare payments.

-The misc tax credits may provide some tax relief.

-The “middle class income tax cut” is actually the same situation as the “high income tax cut.” With today as the baseline it is actually a middle class income tax increase.

Using the proper baseline helps us to understand the impact of the Obama/Republican deal. It will actually be virtually no net change from today so the impace on our depression will be nil.

A little off subject, but actually not much since it deals with budget deficits and spending. I have asked Menzie before when he was going to do the same kind of analysis for Afghanistan under Obama that he did for Bush on Iraq, but the silence is deafening. Here is an excerpt from Bretton Woods Research paraphrasing Richare Vague

Ricardo Menzie engages in the typical mercantilist slight of hand.

I’m sorry, but on several occassions I and few others have gently tried to suggest that you might want to look up the definition of “mercantilism.” This is an economics blog and if you want to be taken seriously you should really learn to use the correct lingo. Here’s the Webster’s definition of “mercantilism”:

an economic system developing during the decay of feudalism to unify and increase the power and especially the monetary wealth of a nation by a strict governmental regulation of the entire national economy usually through policies designed to secure an accumulation of bullion, a favorable balance of trade, the development of agriculture and manufactures, and the establishment of foreign trading monopolies

http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mercantilism

The principal early exponent of mercantilism as a more or less well developed theory of economics was Thomas Mun (1571-1641). Later mercantilist thinkers included Sir William Petty and David Hume. Contrary to what you may have learned at Glenn Beck University, Adam Smith was not arguing against the economics of future socialists, but against the mercantilist theories of his friend and fellow Scotsman David Hume.

So why do you continue to claim that Menzie is advocating mercantilist policies? I don’t know if this is what you had in mind, but the only even remotely plausible connection between mercantilism and Keynesian economics is the kind of thing pointed out (and promptly dismissed) by the economic historian Mark Blaug (Economic Theory in Retrospect). Blaug notes an apparent similarity in the way mercantilists and Keynesians treat MV=PT, with the emphasis on the “T” rather than the “P.” So mercantilists did advocate public projects so that money wouldn’t just sit around literally collecting dust. But that similarity is sophomoric and superficial. And it’s especially weird to hear charges of mercantlism coming from someone who is a “gold bug” such as yourself. Mercantilists believed in building up hoards of metallic species.

Menzie,

Did you even bother to read the whole article? You open with:

“Professor Mulligan asserts that the payroll tax cut will have little effect on output, even in sticky price Keynesian, and New Keynesian, models”.

And Casey Mulligan finishes his post with:

“In my view…the proposed payroll tax cut increases the benefits and reduces the costs of employment and will result in more employment among people earning less than $100,000 a year”

And I’m not exactly sure what

Menzie-

I found some of what I was looking for at – http://www.cbo.gov/Spreadsheets.cfm

This is probably old hat for you, but prior projections are available and also discussions of uncertainties in their forecasts.

Menzie,

Certainly payroll tax cuts are stimulative, but will we not see pressure from the anti-social security gang to cut benefits given how unlikely it is that we will be able to undo the payroll tax cut, and now all the anti-social security gang will have much more dismal projections of doom and “bankruptcy” and so on to back up their arguments for benefit cuts sooner and bigger and so on?

Phil Rothman: I am somewhat sympathetic to your argument; but let’s not forget that Senate House Republicans did vote overwhelmingly against this measure.

Rich Berger: Glad you found the spreadsheet; I was going to link to that, as well as the most recent CBO assessment (I keep on referring to these assessments each time this question comes up on Econbrowser; there is also a Batchelor paper which assesses as well OECD forecasts, in comparison to private sector average forecasts). Of course, 2slugbaits is absolutely correct (replying to markg so I don’t have to) in noting that CBO forecasts are conditioned on current law, so the fact that they do so well relative to private sector forecasts (average thereof), despite the latter being conditioned on expected policies, is surprising. But that is another interesting issue.

Ricardo: Gee, I’ve kept on asking if you now retract your assertions that Al Qaeda operating out of pre-invasion Iraq (which was the basis for your argument that our invasion in 2003 was justified) were accurate. But, heck, I’ve seen no retraction. Nor have I seen any response of yours to the critiques of your definitions of “mercantilism” and “inflation”, which I are the most bizarre and detached from reality I’ve seen in my lifetime. When you own up there, maybe I’ll do what you request. Until then, I respectfully suggest you get your own blog (and see if anyone visits).

Jeff: Why yes, I did read the entire column. He’s still arguing completely from the supply side, and the entire point of my blogpost (did you even both reading/comprehending it?) whs the fact that demand side effects were likely to be much more substantial, but that in any case he did not even nod to demand (he discusses it only in the context of New Keynesian, and Classical-synthesis models).

I would note that CBO’s assessment of the payroll tax cuts is too supply-sidish. If wages are sticky then the employee-tax cut boosts tax tax income but the employer one boosts profits. Given the likely MPC’s the formers probably has much bigger demand effects. Thus for CBO to conclude that the employer-side tax cut is more stimulative they must assume that employers respond fairly strongly to temporary tax cuts. I think there is little evidence for this.

Such payroll tax cuts are welcome but won’t add much to private demand, if at all.

The extreme wealth and income concentration in the US means that only about 40-50% of the ~$110 billion from the payroll tax holiday will be available to the bottom 80-90% of US households that spend virtually all of their after-tax income, whereas some portion will go to paying down debt.

Thus, perhaps $30-$35 billion will be spent for goods and services, which amounts to 0.33% of private GDP.

However, the price of oil is up 18-19% yoy, whereas oil consumption/private GDP is 6-7% (historical recession territory), which is an incremental tax to private GDP less oil consumption of ~1%; therefore, the increase in the price of oil yoy (thanks to Peak Oil, China-Asia demand, and a weaker US$) has already taken the payroll tax cut before the working class get their share, and then some.

Further, the price of oil during ’11 above $75-$80 would be a further drag on working-class households’ spending after the payroll tax cut versus this year.

So, the fiscal deficit will increase by 6% of annualized receipts and 3% of annualized expenditures so far for fiscal ’11 in order to get at best a 0.33% spending boost to private GDP, while most of the increase will be absorbed by the higher cost of US oil consumption/private GDP.

Business profits are at or near record highs as a share of private GDP, in large part because of massive job cuts and capacity consolidation to date. Businesses need paying customers increasing their spending more than they need tax breaks and credits to expand capacity when there is already so much slack now.

And how much of the incremental business investment and consumer spending will go to imported goods from China-Asia, Canada, and the Middle East?

A reminder of how far we have to go, the graph of the day (perhaps the week):

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2010/12/index-of-hours-worked.html

Hours worked (nonfarm business) increased at an average rate of 1.36% annually between 1947 and 2007. Just to get back to trend we would have to have an increase of approximately 12% as of the third quarter 2010.

Demand shortage? What demand shortage?

Gap in NGDP? What gap in NGDP? We’re all just displaying a sudden preference for leisure.

Menzie,

I still don’t think you took a serious look at the article. Perhaps you should have another look. The only thing thing Casey argues is that the payroll tax cut would increase employment, the very same thing you assert. The rest of the article is nothing more than statements of fact about the predictions of various models. Its seems your only beef is that he did not outline his mechanism on how employment would increase in a way that you would have liked. And as “proof” that you have somehow thought through this problem more carefully and your mechanism is the correct one you point to CBO numbers that can be used to support either. My guess on this whole post is that your first inclination when you start to write is to find a familiar foe and jump on them. You found a familiar one in Casey and ran with it, but this penchant for bickering does not reflect well on you.

Perhaps I was too conservative. If one establishes the trendline from 1947-2000 (before the “jobloss” recovery) one gets an average rate of hours worked of 1.56%. That means we have to have an increase of about 28% just to get back to trend. (Sounds kind of like GD II doesn’t it?)

Jeff: Thank you for your psychoanalysis. You seem to think if the “bottom line conclusion” matches, then there should be no argument. But I would say that it critically matters from both an empirical standpoint and a policy standpoint what channels one thinks the process works through. If one takes the supply side approach, then the extent of increase depends critically on the elasticity of labor supply (you might wish to consult this post). My view is that this elasticity is fairly low, so the impact is quantitatively small (Prof. Mulligan does not state how much he expects employment to increase). On the other hand, working through the demand side, the impact could be substantially larger.

I hope this clarifies why a “bottom line” sort of analysis is insufficient for those who wish to pursue the analysis of issues from an intellectual perspective.

Menzie,

No, I never said a bottom line analysis was sufficient. Perhaps you should re-read my post as well. I simply pointed out that as “evidence” in your favor you linked to projections that supported both arguments. The CBO’s projections do not support your suggested mechanism over any other that leads to a net increase in employment. I hope this clarifies what constructing a proper argument looks like.

I just bought a brand new model, top of the line Prince tennis racket. It’s supplied by China, but the thieves at Prince extract a high margin for design and marketing.

Also bought a cool new Sony Walkman mp3 player. It too is supplied by China, but the thieves at Sony Japan extract a high margin for design and marketing.

That’s my only planned demand for 2011, outside of necessities and greens fees. So I’m afraid everyone else will need to kick in substantial demand if we are to close that Big Output Gap I keep hearing about.

Don’t worry about the deficit, social security, state, local, or federal pensions. That stuff will all work itself out.

Ciao

Cedric Regula,

Or we can watch the poor little old output gap grow larger and larger and the associated government deficits just grow larger and larger.

Oh? Did I make the unpleasant obervation that the two might be related? I’m so sorry. It was so impolite of me.

Au Revoir, Adios, Auf Wiedersehen, Arrivederci, Slán go fóill, Do Widzenia, and Cheerio Good Bye for now.

Short-term money flows have ratcheted up & real-output has followed, accelerating upward. Long-term money flows are still declining – but should reverse by FEB at the latest (taking core cpi & housing with it).

I.e., contrary to Jim Bullard’s (Pres.& CEO-St. Louis Fed) DEC 2 speech:

“Maximum effects on the real economy take 6 to 12 months and CAN BE DIFFICULT TO DISENTANGLE, but should be conventional as well”

, economic lags are not “long & variable” (as Friedman & Bullard pontificated).

The lags for monetary flows (MVt), i.e. the proxies for (1) real-growth, and for (2) inflation indices, are historically (for the last 97 years), always, fixed in length.

This just marks the end of Social Security. The demand benefits will be short lived and might reduce unemployment a small amount.

The Repugs are skilled, give them credit – they have drowned the biggest baby of them all with this one.

Menzie, why are you calling permanent income tax increases “tax cuts”? Nobody’s income taxes are going down.

I like the payroll tax holiday. The employed get a boost and the unemployed get UI benefits.

Jeff: Hmm. I read Professor Mulligan’s concluding paragraph:

And I infer from context — and my understanding of the focus on costs a supply side interpretation. Maybe you don’t, but I think most informed macroeconomists would side with my interpretation.

With respect to CBO’s assessment of the channel through which the reduced payroll tax on employees works, it might have been useful for you to read the CBO document which provides the basis of the Figure 2 (page 22):

So, with all due respect, I do not understand your arguments. They do not appear to me to be at all substantiated.

Menzie,

My basic point was simple, and wasn’t even economic. I was simply pointing out that your original post phrased Casey’s post as one in which he was arguing that the payroll taxes would have no effect on output, something it clearly was not. That is it. Now we can sit here and try and read into his article and infer what channel(s) he had in mind when he said this, but that is beside the point and I don’t see that as a productive exercise at all. Who knows what he had in mind? He doesn’t state it explicitly and I’m certainly not going to criticize him because I think he was thinking about the wrong one.

And as an exercise in unbiased thinking, I will point out that the channel through which the CBO suggests the effect will take place (and I image is the same channel you have in mind) is implicitly assuming that prices are flexible-something that sounds a lot like what Casey suggested.

Jeff: Well, taken to that level, please refer to the first sentence of the post:

I don’t see either of us saying “zero effect.” If we can’t agree on what I wrote, then I don’t see how we can proceed.

Jeff Casey Mulligan is setting up a strawman argument about how he imagines a “sticky price Keynesian” model might apply in the current context. The “sticky price” model that he has in mind is something that is appropriate only when a recession is due to some kind of supply side shock. I’m just an interested amateur and not an academic economist, but I don’t know of any serious Keynesian economist who would argue that the solution to today’s economic maladies is a lower real wage. Mulligan makes a not-so-veiled swipe at the Krugman model (you have to follow Mulligan’s link) in which Krugman argues that expanding the labor supply in a liquidity trap actually makes things worse. Krugman’s argument is actually a fairly standard analysis from an earlier era. For example, you can find Tobin outlining almost exactly the same argument, to include the dominance of the Fisher effect over the Pigou real balance effect leading to an upward sloping AD curve. Tobin builds from his favorite IS-LM model to show how you end up with an upward sloping AD curve in a liquidity trap. The point is that when recessions are due to weak aggregate demand from too much savings and not because of some supply shock, the “sticky price” model that Mulligan hauls out just isn’t the appropriate Keynesian model anyway; so when Mulligan tries to shoot it down he is really shooting at a strawman. And this is because Mulligan is forever stuck in the RBC tradition. In Mulligan’s world there is no AD curve, only stochastic technology shocks and voluntary unemployment…all things that work upon the AS curve. So the point of Menzie’s post was entirely correct: Mulligan forgot about the AD curve. The rationale for a payroll tax holiday on the employee’s contribution to the FICA tax isn’t because it will lower labor costs (i.e., push out the AS curve), but because it will increase aggregate demand.

Menzie,

I have never expected you to comment on the cost of the Afghanistan war since your posts are more politically motivated than economically motivated. I am just pulling your chain.

Concerning mercantilism, only in the modern era through the political efforts of dominant economists (Keynesians) has mercantilism been restricted to international trade. The early critics understood that mercantilism first begin with the political alliance through a hierarchical bureaucracy. At first this was between the king, his nobles and large-scale merchants or traders. This is how “mercantilism” got its name. Adam Smith called it a system of systematic state privilege, as he recognized that political actions would of necessity involve international trade, since foreign traders make convenient targets because they do not have as significant a voice in local politics.

Keynes recognized that his General Theory contained the same fallacies as the mercantilists and so he dedicated the entire 23rd chapter to obscuring mercantilist criticism, but even Keynes did not restrict his 23rd chapter to foreign trade alone. Keynes primary obsession was with criticizing free markets because the success of free markets refutes his whole theory.

The refutation and exposure of mercantilism was present before Adam Smith most notably in the writings of Turgot who seemed to address Keynes directly:

“Whatever sophisms are collected by the self-interest of a few merchants, the truth is that all branches of commerce ought to be free, equally free, and entirely free.”

After Adam Smith came Ricardo, John Stuart mill, Bastiat, Bastable, Marshall and Taussig and that does not even mention the host of Austrians. A comprehensive list of critics of mercantilism is too large to mention.

In an article in 1963 Murray Rothbard made the following observation:

“Mercantitlism has had a “good press” in recent decades, in contrast to 19th-century opinion. In the days of Adam Smith and the classical economists, mercantilism was properly regarded as a blend of economic fallacy and state creation of special privilege. But in our century, the general view of mercantilism has changed drastically.”

Rothbard gives what is the best definition of mercantilism, unadultrated by modern Keynesian revisionism:

“…it [mercantilism] was a comprehensive system of state-building, state privilege, and what might be called ‘state monopoly capitalism.’

As the economic aspect of state absolutism, mercantilism was of necessity a system of state-building, of Big Government, of heavy royal expenditure, of high taxes, of … inflation and deficit finance, of war, imperialism and the aggrandizing for the nation-state. In short, a politico-economic system very like that of the present day….”

So my use of “mercantilism” is not the Keynesian meaning of the term but the traditional meaning of the term. And with this definition it is easy to see that mercantilist thinking has caused our current crisis.

Minzie, I realise that your area of study is Keynesian so your ignorance of the history of mercantilism is understandable. But thanks for asking. It gave me a chance to stimulate the interest of others.

This is strawberry picker trying to earn some belated MMT points.

Mosler over at moslereconomics.com has taken credit for the payroll tax holiday making it into the mainstream. What would the economists here say about that? I am thinking about that movie “and the band played on” and the genome sequencing battle where president bill clinton had to walk out with both camps to keep peace. I am looking at this from a historical perspective (I like to study meme propagation on the net), who here would attribute Mr. Mosler as the economist who brought the payroll tax holiday into the mainstream? If not him – who? Thanks.

Ricardo

Your summary of mercantilism smells like some stuff that you copy/pasted without actually understanding the contexts of the arguments. Regarding Keynes’ and the 23rd chapter; Keynes was not saying that mercantilism was a good econommy theory, he was saying that mercantilist thinkers correctly understood that the interest rate did not always equate savings and investment. He did not say that mercantilists had the right answer, only that they were at least aware of the problem of insufficient investment demand, which was something that classical economists denied could ever happen. So I think you need to reread Keynes’ chapter 23.

You also don’t seem to appreciate the difference between those who advocate big government because of market failures and mercantilist reasons for advocating govt involvement in the economy. Mercantilists believed that an economy existed for the purpose of facilitating royal power. For example, “national security” cold war type conservatives from the early 1970s were mercantilists. Go look at some of the defense plans from the mid-70s from guys like SECDEF Rumsfeld (his first time) or SECDEF James Schlesinger. Their view was that the reason a nation needed a strong economy was so that it could pursue strong imperial policies. Energy independence was seen as a good thing because it gave nation states more political latitude in playing the game of power politics. And nuclear theorists like Paul Nitze argued for a strong industrial base because it meant that a country could better absorb a nuclear strike and emerge victorious after a nuclear war. Dick Cheney is also a mercantilist because he sees the raison d’etre for economics as a tool in the further aggrandizement of the national security state. In the mind of a mercantilist freedom does not mean personal liberty, it means the freedom of action of nation state actors. It’s a military view of freedom…I know, I work for DoD and I encounter this mercantilist view of the world every day.

Compare that view with a “green” view of govt involvement in the economy. It’s quite different and is based on welfare economics, negative externalities and de-emphasizing military power. Quite different, but yet in your formulation it’s all the same thing.

Sorry, but you just don’t understand what the term means.

slug,

Actually you have a better understanding of mercantilism than Menzie. I actually appreciate your post above. You paragraph on the military is almost spot on. Now you just need to expand your thought process to all government schemes.

But enough with the agreement. Let’s see where we disagree.

Your wrote:

You also don’t seem to appreciate the difference between those who advocate big government because of market failures and mercantilist reasons for advocating govt involvement in the economy.

This is where you need to do more research on your own rather than taking the word of others. All the supposed “market failures” have actually been government failures based on mercantilist principles.

The whole principle of “the problem of insufficient investment demand” is mercantilist to the core, and you are right about Keynes saying his theory agreed with mercantilism at this point. (To be fair to Keynes he did not say mercantilism was totally right. He only said that where his theory was mercantilist, mercantilism was right.) The wole concept of “insufficient investment demand” is based on the false theory that the government can know then properly act to create sufficient investment demand, but who determines what sufficient investment demand is and who should receive the benefit of that demand? In the mercantilist/Keynesian world it is the political class, big business and government. But this is foolish on its face because only the people can determine sufficient investment.

Where you support mercantilism is its whole foundation, that the government through its coercive power can forcefully take from one group and give to another, rearranging the deck chairs, and benefit society as a whole. This is nothing but rationalized theft.

This very act of redistribution attacks the idea of the people deciding for themselves. It is the idea that those in government know best how to spend the money of everyone else. And this is the essence of mercantilism and it is the mercantilist rationalization whether justifying military spending or the giving of billions of dollars to construction workers in New York City.