Trade Openness, Fiscal Space and Exchange Rate Adjustment

Today, we are fortunate to have as guest contributors Joshua Aizenman of UC Santa Cruz and Yothin Jinjarak of the School of Oriental and African Studies of London University.

This post draws upon Aizenman and Jinjarak (2011).

The dire outlook of the global economy in the second half of 2008 necessitated unprecedented fiscal expansions in most OECD and emerging-market countries. The resultant fiscal stimuli focused attention on the degree to which countries possessed “fiscal space” and on ways to apply it in a counter-cyclical manner. But what does “fiscal space” mean? In attempting to clarify this fuzzy concept, Heller (2005) defined it “as room in a government’s budget that allows it to provide resources for a desired purpose without jeopardizing the sustainability of its financial position or the stability of the economy.”

In our recent paper, we aim at defining a measurable “fiscal space” variable, and apply this concept in the context of the global crisis. A conventional metric, used by Maastricht criteria and frequently by scholars is the public debt/GDP. They question the degree to which normalizing public debt and fiscal deficit by the GDP is an efficient way of comparing fiscal space across countries and across time. A given ratio of public debt/GDP, say 60%, is consistent with ample fiscal space in countries where the average tax collection is about 45% of the GDP [Norway]. But, with a limited fiscal space, in countries where the average tax collection is about 10% [China, India].

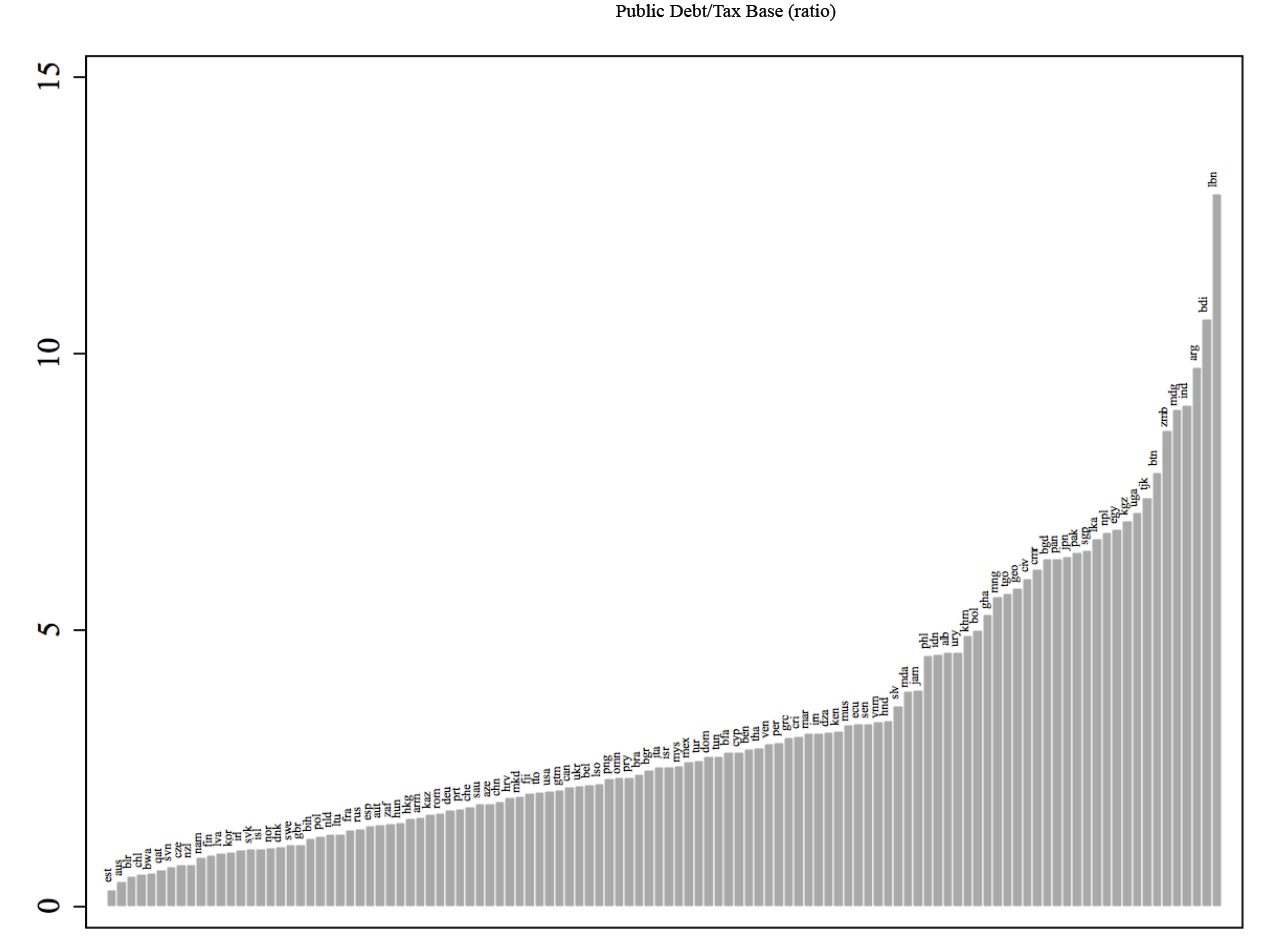

A useful notion is the de facto tax base, measuring the realized tax collection as a fraction of the GDP, averaged across several years to smooth for business cycle fluctuations. The ratio of the outstanding public debt to the de facto tax base, or the tax-years needed to repay the public debt is measuring the de facto fiscal space. Figure 1 reports this measure of 123 countries, subject to data availability in 2006. It shows the wide variation in the tax-years needed to repay the public debt, from well below one year in Australia (indicating a high fiscal space), to about five years in Uruguay, and above 9 years in India and Argentina (indicating a very low fiscal space) (See Aizenman, Hutchison, Jinjarak, 2011). For most of the countries in our sample, the tax-years it would take to repay the public debt in 2006 were below three years. Figure 1 is consistent with the notion that, even without increasing the tax base, a fair share of countries had significant fiscal space in 2006.

Figure 1: De facto fiscal space measure based on public debt and tax revenue. Notes: This figure plots country’s fiscal space as measured by inverse of the tax-years needed to repay the public debt. De facto fiscal space measure based on public debt and tax revenue is defined by [2006 Debt/GDP] ÷ [2000-05 Average Tax Revenue/GDP.

They apply the de facto fiscal space in order to explain the cross-country variation in the fiscal stimulus during the aftermath of the global crisis. The pre-crisis tax revenue measures the de facto tax capacity in years of relative tranquility during the early 2000s — the Great Moderation. The presumption is that a lower pre-crisis public debt and lower average fiscal deficits relative to the pre-crisis tax base imply greater fiscal capacity to fund stimuli using the existing tax capacity.

Figure 2 summarizes the averages of these measures for the low, lower-middle, upper middle, and high-income. The Figure suggests that in 2006, the middle income countries’ fiscal space was higher than the low income countries. While the debt overhangs [2006 public debt/GDP] of the low and lower middle income countries are slightly above the other groups, their ratio to the tax base is much higher than that of the upper middle income and the OECD countries. This in turn implies that the low- and lower-middle income countries may have more limited fiscal space than the upper-middle income and the OPEC countries. Consequently, the fiscal stimuli of the richer countries would have the side benefit of helping the poorer countries in invigorating the demands facing lower income countries.

Figure 2: De facto fiscal space by income classification.

The 2008-9 crisis led to a significant fiscal stimulus in the US, Japan, and Germany, the magnitude of which increased from 2009 to 2010, reflecting various lags associated with fiscal policy. In the US, Germany, and the UK, massive “bailout” transfers to the banking systems were put in place as an attempt to stabilize the financial panic. In Germany and the UK the size of these transfers to the financial systems exceeded the fiscal stimulus to the non-financial sector. Similar trends, though in varying intensity, were observed in emerging markets. China, South Korea, and Russia provided front-loaded fiscal stimulus at rates that were well above the one observed in the OECD countries. Notable is the greater agility of the emerging markets’ response relative to that of the OECD countries, reflecting possibly a faster policy response capacity of several emerging markets. This observation is remarkable considering the earlier evidence of the fiscal pro-cyclicality observed in emerging markets and developing countries during the 1980s-90s [see Kaminsky, Reinhart and Végh (2005)].

We perform a regression analysis, accounting for the cross-country variation in the fiscal stimulus during 2009-2011. We find that a greater de facto fiscal space, higher GDP per capita, higher financial exposure to the US, and lower trade openness were positively associated with fiscal stimulus/GDP during 2009-2011. The economic magnitude of these effects is large. Lowering the 2000-05 public debt/tax base from the average level of low-income countries (6) down to the average level of the Euro minus the periphery countries (2.3), was associated with a larger crisis stimulus in 2009-11 of 2.8 GDP percentage points. A decrease in the public debt/tax base revenue by one standard deviation (2.4) was associated with an increase of the fiscal stimulus during 2009-2011 of 2.2 percent of GDP.

Intriguingly, we found that higher trade openness had been associated with a lower fiscal stimulus, and higher exchange rate depreciations. A possible interpretation is that, as fiscal multipliers may be lower in more open economies, these countries opted for a smaller fiscal stimulus, putting greater weight on adjustment via exchange-rate depreciation (“exporting their way to prosperity”). The economic magnitude of these factors is sizable. An increase of trade openness ((Export+Import)/GDP) by 1 standard deviation (0.5) is associated with a higher cumulative depreciation during 2007-09 of 7 percentage points. The results validate the presence of gains associated with greater fiscal coordination among countries. A coordinated fiscal stimulus may generate positive spillover effects, mitigating the reliance on competitive depreciations. In a companion paper, we also study the usefulness of the de facto fiscal space measures by showing that they account better for sovereign spreads of countries than the more conventional public debt/GDP [Aizenman, Hutchison, and Jinjarak (2011)].

These results validate that the de facto fiscal space [tax revenue as a share of the GDP, averaged across the business cycle] provides a useful way of normalizing macro public finance data, and account well for the patterns of fiscal stimuli and sovereign risk during and after the global crisis of 2008-9.

This post written by Joshua Aizenman and Yothin Jinjarak.

Joshua Aizenman and Yothin Jinjarak wrote:

The dire outlook of the global economy in the second half of 2008 necessitated unprecedented fiscal expansions in most OECD and emerging-market countries.

They lost me on the first sentence. To make such a blanket statement with no foundation calls into question the whole paper. The “unprecedented fiscal espansions” caused the “dire outlook of the global economy” in 2008.

Earth calling Ricardo. The drop-off in US GDP occurred in 2008Q4; ARRA was passed in February 2009. (This post presents a graph if you are unable to access and plot data on your own.) Are you invoking a “time tunnel” argument, or some extreme form of perfect foresight?

Fascinating. I am a bit puzzled by the use of both imports and exports to measure trade openness. Would the trend would be more pronounced using only imports? This might better test the proposed explanation. The ability to import tends to dilute the fiscal multiplier I would suppose. An alternative explanation is that governments committed to free imports also dislike government interference in markets, but the same may not be true of exports.

Interesting, but I’m a bit surprised by the tax base for Greece, which the authors report as 32.7%, which higher than the US tax base. My other concern is how much fiscal space there really is for Europe’s periphery given that the ECB seems to be of the opinion that what’s good for Germany and France is good for the EU. The US at least enjoys an accommodating Fed, which gives us some opportunity to exercise whatever fiscal space we need. Not so with the PIIGS. The authors kind of hint at this when they discuss exchange rates and Mundell-Fleming, but not in a direct way.

Lesson learned: another opportunity to slam Bush #43 for leaving us with less fiscal space when we needed it most.

Ricardo to Ivory Tower Air Traffic Controller Menzie: Check out our deficit since about 2001

http://www.usgovernmentspending.com/downchart_gs.php?year=2000_2016&view=1&expand=&units=p&log=linear&fy=fy12&chart=G0-fed&bar=0&stack=1&size=1259_631&title=&state=US&color=c&local=s&show=

Then check out MZM since 2005 as a bonus.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/MZM

Both fiscal and monetary excess gave us our “dire outlook in the global economy.” And the stats above are just the US. Consider the PIIGS, Iceland, and a host of other fiscal and monetary disasters in the global economy.

Looks like there is a little tension in the economic blogsphering air.

Ricardo: Let me restate. The deficit is an endogenous variable, wherein tax revenues are partly a function of the level of economic activity. In order to see the impact of discretionary fiscal policy, one should examine the cyclically adjusted budget balance to GDP ratio. According to CBO, this variable in 2008 was the same as in 2003. Hmmm.

And monetary policy was, in 2008, primarily monetary policy, not fiscal policy. In your first comment, you noted only fiscal expansions.

So, I repeat my question, ground control to Ricardo, please tabulate the deficits and discretionary stimuli prior to 2008 around the world that caused the simultaneous dropoff in economic activity in 2008Q4.

Menzie, are you saying the massive bush tax cuts were not discretionary? Kind of weird logic there. And certainly the wars were discretionary, that seems pretty clear. And the Greenspan/Krugman/Bernanke low interest housing bubble was discretionary.

Menzie, are you saying the massive bush tax cuts were not discretionary? Kind of weird logic there. And certainly the wars were discretionary, that seems pretty clear. And the Greenspan/Krugman/Bernanke low interest housing bubble was discretionary.

Ricardo,

You reference the PIIGS as an example that the crisis was a product of irresponsible fiscal expansion and deficit spending. It is worth noting however that Ireland and Portugal were running surpluses prior to the crisis (whereas Germany was not for example).

Even from your graphic, it is pretty clear the large deficits began after the onset of the crisis, and were not the leading indicators of it. Further, much of the increase was driven by falls in revenue, (which is the extent to which the deficit is endogenous, of course there are exogenous policy decisions as well) as opposed to spending. You need to decompose these two to really make any use of deficit measures about “fiscal expansion”, and again the timing is all off to be consistent with your story. Also the M2 graph doesn’t show growth outpacing that of the past several decades, and you have not adjusted for growth in the economy, so it was not as if there was a huge jump in trend prior to the crisis to make it even a candidate of culpability (and as Menzie notes this is not fiscal policy which was your original argument). Obviously financial factors/debt/leverage played a major role in triggering the crisis (exacerbating what may have been otherwise reasonable, or slightly too low, interest rates given the economy), but to say the majority of the causal story of the crisis in OECD nations or even emerging markets was sovereign debt (or even a noteworthy portion of it) is a sickening version of revisionist history. Though I do happen to agree it was misguided of the US to eliminate the surpluses with unemployment relatively low, just in preparation for future costs/possible downturns.

pete: Sure, they were discretionary, and were crucial to limiting our scope for action on the fiscal front in 2008, but we didn’t have a macro blow-up in 2000 as a consequence of the tax cuts of 2001 and 2003 — that is there was no “time tunnel” or “quantum leap” (pick your favorite time-travel sci fi TV show) effect.

Oh come on….the impact of the deficits is the cumulative debt. They were not one year tax cuts. Anyway I don’t see how these discretionary deficits and resulting cumulative debt limited the scope for action. The limit was purely political, not a real (economic) limit, at least according to Krugman. I see now though that the argument is that the CURRENT 10% deficit (G-T)/ GDP is not a stimulus since it is not discretionary? Only discretionary deficits can be stimulative? So you keynesian types need 25% deficit/GDP to be stimulative since 10% is built in?

Wow! Menzie, are you saying that since it all came to a head in 2008 and the fiscal expansions did not come until after 2008, that the current “dire outlook of the global economy” is not Bush’s fault? You are saying that it is all on President Obama’s watch?

What an admission. LOL! Thanks for taking the bait.

“The dire outlook of the global economy in the second half of 2008 necessitated unprecedented fiscal expansions in most OECD and emerging-market countries”

Taking a step back from what Ricardo said, this statement alone needs backing up – unless we accept Keynesian economics on faith. There are many economists who would take great issue with this.

Ricardo: Just to remind you, the crash in output happened in 2008Q4, worldwide. You can dispute that in any alternate universe you want, with alternate (virtual) data. But in my world, that’s when output collapsed, and in my world, George W. Bush was president at the time.

Jason R.: Yes, some do. Here’s a list. If you wish to be associated with them, by all means. I know Prescott and I do not see eye to eye.

Jason R I don’t know that you need to take Keynesian economics on faith; afterall, you can always ask if the theory holds up internally and if it more or less accurately predicts what will happen. The standard Keynesian approach predicted that given the size of the ARRA stimulus we should expect a spike in GDP growth in 2009, with fading growth in 2010 and 2011. And that’s exactly what we got. Recall that the RBC economists were predicting zero growth in 2009…until after-the-fact when they tried to retrospectively change their forecasts after the numbers were already in. Of course, if you’re an RBC economist, then we don’t have involuntary unemployment today anyway, so what’s the problem? It’s all just a “technology shock” due to autonomous changes in labor/leisure trade-offs. Sure it is. And as for the Austrians, well…talk about mumbo-jumbo economics. Austrians have a very big theory about economic collapses and no theory about economic recoveries. If you’re an Austrian, a bright sunny day is just a harbinger of rain and storms tomorrow. If Austrians were weathermen they would tell you to bring your umbrella to work everyday. If you’re a Tea Party Republican, then you don’t have any coherent economic theory except tax cuts are the cure for everything. Too much govt revenue choking off growth…call for tax cuts. Not enough revenue, then let’s bring on some of those self-licking supply side tax cuts that pay for themselves with plenty left over. You betcha. So when all is said and done it’s really only Keynesians that have anything to contribute to the current problem.

Joshua Aizenman and Yothin Jinjarak wrote:

The dire outlook of the global economy in the second half of 2008 necessitated unprecedented fiscal expansions in most OECD and emerging-market countries.

Back to the first sentence. Have you ever noticed how the fiscal/monetary stimulus economists spend a lot of time telling us to pump in more stimulus to correct the crisis but just accept the actual crisis as a given? They spend very little time trying to understand why be got into the crisis to begin with. That was true with the analysis of the Great Depression and the Great Inflation, and it has been no different with the Great Recession.

Have you seen any Keynesian or monetarist analysis of the demise of Fannie and Freddie and how they contributed to the credit crisis? But they have written reams to explain away why the deficit declined after the Bush tax cuts – that is until Bush exercised is Keynesian stimulus muscles and sent the economy into a TARP tailspin.

Ricardo: Hmm. I seem to recall sitting in my office at the Old Executive Office Building at end of 2000, contemplating the Bush tax cut plans, and saying to myself, well that’ll end our problems with budget surpluses. And gosh darn it if I weren’t right.

But little did I know he also planned to dismantle the financial regulatory apparatus and let housing boom to, well, you know what. So not everything is fiscal policy (or monetary). But one would never know that from reading your tracts.

By the way, going back to your universe, and our first exchanges on Econbrowser (in your Dick incarnation), did we ever find WMDs in Iraq? Oh, and I do recall your linking 9/11 to Saddam Hussein — I would’ve laughed for days except for the fact it was so tragic that so many people like you were duped into supporting a war that led to thousands of deaths.

Menzie Chinn –

I’m not really clear as to the point of your comment. To clarify, the point of my original comment was that your post starts with a broad, sweeping assumption that is clearly controversial even among well-regarded economists, and then you base the rest of your argument on it. The post would have been stronger if it contained backing for the initial claim.

2slugbaits –

“The standard Keynesian approach predicted that given the size of the ARRA stimulus we should expect a spike in GDP growth in 2009, with fading growth in 2010 and 2011. And that’s exactly what we got”

Two points: 1) there is wide debate on the cause of the 2009 rebound 2)I’m not a keynesian, old school, new school, or otherwise, but I too thought government stimulus would boost the economy in the short term. My concern is the longer term consequences, including such things as an unsustainable deficit, business investment focused on goods and services that for government spending and not private spending, etc.

Menzie,

I read my comments on the link you provided but I did not see any references to WMD. On WMDs I did take the same position on them that Bill and Hillary Clinton too, that John Kerry took, that many of Saddam’s closest generals took, and a majority of congress took in voting for action in Iraq. Were there WMDs that were moved to Syria? Or did they never exist? Today there seems to be strong evidence that if they existed they were very rudimentary. But speaking about WMDs in Iraq years later, Monday morning quarterbacking, is a different thing from dealing with a potential life or death decisions. Perhaps WMDs should not have been part of the justification for entering Iraq in hindsight, but that does not eliminate all of the other reasons. Enough on Iraq. It is an ancient issue.

When you talk of those who dismantelled the regulatory agency can you really ignore Barney Frank and Chris Dodd? Do you really think that it was Bush who wanted to make Fannie and Freddie into a Democrat slush fund? Or make Franklin Raines obscenely wealthy?

I have serious disagreements with Bush on his economic policies and I do believe that he and Henry Paulson were significantly instrumental in putting us in our current predicament, but regulation was the instrument used to defraud the taxpayers and drive us into the real estate credit crisis not a dismantling of regulations.

Do you deny that today over 95% or all homes are financed with govermnet assistance? Regulation? The loan business has been nationalized. Does the government regulate itself?

Our crisis was not because of under regulation but over regulation. It was caused by congressmen with no real estate experience thinking they could run all the real estate transactions in the country. The crisis was because the free market in real estate has been virtually destroyed.

The link that I made between Saddam and 9/11 was the presence of training camps in Saddam’s Iraq. Are you saying that you deny they existed?

Apologies, the “Anonymous” post that starts with “I’m not really clear as to the point of your comment…” is mine.

-Jason R.

“Our crisis was not because of under regulation but over regulation.”

Say hello to the Really Big Depression of, oh, let’s say 2016.

Dick: You stated those links as a casus belli. Do you deny that? And it’s an ancient issue? I think we still have tens of thousands of troops there, expending billions of dollars per day. For you, it’s ancient history. But I think those who have a bad track record for analytical ability should be held accountable.

Menzie,

Here is a video you might find interesting.

http://www.liveleak.com/view?i=eab_1201152136

Is this one of the people you believe should be held accountable?

Just for the record, President Obama told us on Wednesday night that troops had been removed from Iraq. Is he also one of those who should be held accountable?