We finally get our debt-ceiling deal, only to watch the S&P500 fall 3.7% from Thursday’s close. What gives?

Let me begin by suggesting that the debt debate lumped together three issues that I regard as separate problems. There was first the immediate challenge of how the U.S. government was going to pay its bills for the rest of August. Second is the near-term need to bring unemployment down– we need to see more robust economic growth in order to get Americans back to work as quickly as possible. And third is the daunting challenge of putting U.S. fiscal policy on a sustainable long-run course– debt cannot continue to grow as a multiple of GDP, and something needed to change to ensure that it did not.

The first problem– finding a way to meet the government’s immediate spending commitments– was entirely a monster of Congress’s own creation. Congress had stipulated a certain level of spending. Congress had further approved of taxes that resulted in revenue substantially below those spending levels. It would then seem obvious that the government needed to borrow additional funds to make up the difference. Yet Congress had ruled that out as well in the form of a standing limit on how much could be borrowed. It was unclear how this was all supposed to be reconciled, and how exactly items such as Social Security payments, soldier salaries, and sums owed creditors were all going to be paid this week. The clean answer would of course have been to raise the debt ceiling as a stand-alone act, and separately modify the spending or tax policies if legislators didn’t want to keep on seeing the total sum borrowed continue to rise.

So perhaps we should be thankful that at least one thing we got out of the last-minute deal was a lifting of the debt ceiling, allowing August federal payments to be made on schedule. But I think there was some damage done by carrying the drama as far as we did. People were getting nervous about how this would all play out. When people get nervous they sit on the sidelines, and when folks sit on the sidelines, the economy can stall. Concerns about how this would all end up could have been one factor contributing to the July plunge in consumer sentiment, and that loss in confidence could also be relevant for recent weakness in consumer spending. I found myself getting calls from friends worried about what the wrangling in Washington might mean– was it still safe to be holding T-bills, and if not, where should people put their money? A few years ago, hardly anybody was talking seriously about the possibility that the U.S. might fail to honor its statutory debt. Today, there is open discussion of downgrading U.S. debt. Although we got through this episode, a residual uneasiness is still going to be there, and may leave us with less room to maneuver when a real problem shakes people’s confidence.

|

The second problem– getting the unemployed back to work– is one that could only be aggravated by recently debated measures. I share the strong concern held by many about the need for long-run fiscal sustainability. But I feel equally passionately that cutting near-term spending is counterproductive. Reducing government spending is taking away somebody’s income, namely, that of the government employee, contractor, or recipient of transfer payments. Granted, we will soon need to start making exactly those cuts. But the time to do so is when there are private sector jobs available to pick up the slack. If we try slashing the 2012 budget, it will just add more people to the current swollen unemployment rolls. Again, perhaps another thing to be thankful for in the budget deal is that the spending cuts it implements for 2012 appear to be pretty minor.

And how about the long-run objective– putting fiscal policy on a responsible course for the next decade? The legislation sets a target of cutting the cumulative deficit by $1.5 trillion over the next decade, with a complicated series of contingencies and triggers that are supposed to ensure this happens. What bothers me about this is that there has been no real discussion or agreement as to exactly what we’re going to do or how we’re supposed to do it. And the reason for that absence of real discussion is pretty simple. The voters want to believe they can get something for nothing, and the politicians are only too willing to promise exactly that.

Dealing responsibly with the long-run challenge in a way that does not destabilize the economy in the short run strikes me as a fairly straightforward problem. Measures such as raising the eligibility age for Medicare and Social Security and increasing the co-pay for Medicare on a defined schedule over time achieve exactly those objectives. Perhaps I will be pleasantly surprised and all this will eventually emerge from the sequence of procedures that today’s legislation puts in play.

I know, nobody else was all that happy with the deal either, and you could argue that the deal does at least muddle through, in its own way, with all three objectives I articulated above. So if the deal is almost sort of reasonable, how come the stock market tanked on the news?

|

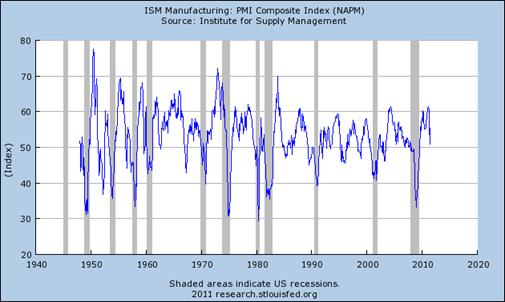

One answer is that there has been other unfavorable news arriving at the same time. At the top of the list I would put yesterday’s manufacturing ISM report. This is a diffusion index, for which a value above 50 indicates that more facilities are reporting improvements than are reporting declines. The July value for the index (50.9) means that manufacturing is still expanding. The problem is, if the economy were actually growing, we expect to see a number above 50– the historical average value for this index is 52.8. And during the last year, this measure had been averaging 57.7. Manufacturing had been the one bright spot in the economy. Had been– past tense.

|

And today we received so-so auto sales numbers for July. The seasonally unadjusted number of light vehicles sold was up ever so slightly from that for June 2011 or July 2010, but in each case the increase is less than 1%. The one potentially encouraging detail is that sales of domestically manufactured vehicles were showing decent gains, with low numbers for Japanese imports holding down the totals. The Wall Street Journal offered this analysis:

Japanese auto makers have been hurt by dwindling dealer inventories, a lingering effect of the March 11 earthquake that disrupted auto and parts production in Japan and North America….

Despite the slowdown, executives expressed confidence that industry sales will improve. They said more Toyota and Honda vehicles will arrive on dealer lots in the fall, allowing those companies to discount prices more heavily.

So things may improve. But it certainly appears that the first half was pretty dreadful for the overall economy, and the promised rebound didn’t begin in July.

Which is enough to deflate whatever enthusiasm you might have felt at the news that the federal government has figured out a way to honor its scheduled payments for the next few months.

Perhaps the problem with economic analysis is that everyone is looking at the big picture… GDP, etc.

It only takes a loose connection in an engine control module to stop the whole car. This economy has two loose connections… the destruction of personal wealth in the middle class and the destruction of jobs in the non-college-educated workforce. These are structural, not cyclical, and no matter how many “spark plugs” are changed, the economic engine is stalled. Pouring more gas into the tank achieves nothing at this point.

As long as the tax and regulatory policies are counter-growth, extending unemployment benefits simply delays the trip to the junk yard.

Dear Professor Hamilton,

I found the opinion piece, World War II Stimulus and the Postwar Boom”, by Professor Rumelt in the 7-30-2011 edition of the WSJ to be very interesting. He claims that government policy didn’t stimulate personal consumption (as Keynesians are trying to do today), but rather enforced thrift. He also says, “If one wanted to replay he economics of World War II (without the war), it would mean high consumption taxes aimed at the middle class, and putting 30 million Americans to word at minimum wage or less”. He then says, “The key policy aims should be removing the tangle of tax, policy, regulatory and human capital impediments to domestic private investment. Not only does the federal government need to fix its balance sheet, citizens need to fix their own balance sheets after an orgy of debt driven consumption over the past 25 years.

Any thoughts on this?

That was the last, best chance for structural reform that could have gotten us on a fiscally sustainable path, and Congress threw it away.

Gold sure went nuts though on the political failure. I wouldn’t want to be caught without gold right now!

JDH Nice post, but I do have a couple points of disagreement: Measures such as raising the eligibility age for Medicare and Social Security and increasing the co-pay for Medicare on a defined schedule over time achieve exactly those objectives.

It’s not clear that raising the age for Medicare elibility would reduce costs. As it is, many people already put off medical procedures until after Medicare kicks in. Raising the eligibility age would probably make this problem even worse. There’s no question that rising Medicare costs is the major long run debt driver, but to fix Medicare we need to fix healthcare costs in general. Shifting costs isn’t the answer. I would prefer that Medicare start announcing what procedures it will not cover rather than just delay coverage.

Social Security is not really part of the debt problem. Social Security has its own set of problems that need to be addressed, but fixing Social Security does not fix our debt problem and not fixing Social Security does not make our debt problem any worse. Even the Bowles-Simpson Commission admitted as much in a little noted footnote to their report.

Finally, to the extent that Ricardian Equivalence holds, we should expect that if people perceive Medicare and Social Security cuts are more imminent than they really are, then rational actors will try to anticipate those lower benefits with increased personal saving. That would be exactly the wrong prescription right now. So politicians really need to drive home the point that any benefit cuts are in the far off distant future; otherwise middle and upper middle class income earners might increase savings even more than they are now.

JDH,

“The first problem– finding a way to meet the government’s immediate spending commitments– was entirely a monster of Congress’s own creation.”

Let’s be honest here — this was entirely a monster of Congressional Republicans’ own creation, not “Congress’s”. Dems wanted a clean increase, just like had happened for the last 79 times. This is the first, but sadly for the country far from the last, time that this ludicrous game of kabuki has ever carried real policy consequences. We’ll all be paying this ransom for a long time.

As for why the markets tanked on the news, my take is that they looked up from the GOP-inflicted ‘crisis’ and noticed how weak the US ‘recovery’ is. “Great that the hostage won’t get shot! Too bad he’s got cancer…”

PS

“But I feel equally passionately that cutting near-term spending is counterproductive. Reducing government spending is taking away somebody’s income, namely, that of the government employee, contractor, or recipient of transfer payments.”

So after the debt deal 2012 spending is “only” 24% higher than 2008. They will have to cut a whopping $25B from a 3.7 trillion budget ( or .67%). I thought the increase in spending was supposed to be ‘temporary and targeted’.

I’ll take the counter-argument that spending 25% more on government waste is taking away somebody’s income, namely, that of a productive small business trying to create the jobs you lament are not there.

AS

I am going to answer your question indirectly. Please read Munger’s speech the Psychology of Human Misjudgment, where he speaks at length about incentive caused bias. You will quickly realize that you should (the way Munger and Buffett refuse to read stock reports, etc.) stop reading the WSJ. Every paragraph has a agenda, other than being accurate or useful.

You should ask yourself what is the motive for the piece: the reason is self evident. WWII is the mother of all economic experiments, proving that Keynes was right—to end a depression or steep recession, the government has to borrow and spend mountains of money (and so far we are only in the foothills).

Now, to the people at the WSJ, etc., Keynes cannot be right (otherwise the current debt fight, for example, would be beyond amoral). Consequently they will publish total BS because Keynes has to be disproved.

The fact is labels like consumer or investment or whatever or meaningless to the economy. We could all have one pair of socks, one pair of shoes, a pair of slacks and a t-shirt and eat dirt and still have an economy with the same GDP. Instead of shirts we could make something else and then throw it away, calling it consumption. The labels are generally just tools for people who have an incentive caused bias. If I am an economist for the shirt industry, I will leave K street every morning to lobby for my “consumption.”

Economics is not a science—the economy is a giant confidence game. Debt as a percent of GDP reached its lowest point when Jimmy Carter was President and look at how miserable things were then. To understand the economy requires that one truly play the Grand Game, with an extraordinary tolerance for ambiguity. Very few economists have that talent. Most are academic and then need to write papers to appear relevant. The truth is that real discoveries are rare so 99.9% is useless.

For example, no economic model exists showing how much damage Bush caused to confidence when he lost the war on 9/11 and shut down the economy like a coward. No tools exist to measure the intangible damage we can now see was obviously done.

“As long as the tax and regulatory policies are counter-growth, extending unemployment benefits simply delays the trip to the junk yard”

Yes, taxes are to low and weak financial regulations are sucking from the real economy. Lets reinstall Glass-Steagal and raise taxes rates on the wealthy for more bargaining positions.

Slug makes a great point about Medicare/SS. I think the economy could get a pickup in coming years as Boomers dump the overcharged premiums for Medicare.

I have to second 2slugbaits comment on raising the Medicare eligibility age:

Raising the Age of Medicare Eligibility: A Fresh Look Following Implementation of Health Reform

“As the debate over the federal deficit takes hold, some are proposing to raise the age of Medicare eligibility beyond age 65 as one among many options to reduce entitlement spending. Previous studies, conducted prior to the enactment of the 2010 health reform law, show that an increase in the age of Medicare eligibility would be expected to reduce Medicare spending, but also increase the number of uninsured 65 and 66 year olds, many of whom would be expected to have difficulty finding comparable coverage on their own, either because of prohibitively expensive premiums or coverage limitations imposed on those with pre-existing conditions. Our analysis differs from prior analyses of raising the age of Medicare eligibility primarily because it takes into account key provisions in the 2010 health reform law, which provides new avenues to public and private health insurance coverage for those under age 65, including expanded Medicaid eligibility and a new health insurance Exchange

This study examines the expected key effects of raising the age of Medicare eligibility to age 67. We assume full implementation in 2014, rather than the more common assumption of a gradual increase, to illustrate the likely effects once fully phased in. We also assume full implementation of the 2010 health reform law. A full discussion of assumptions and their expected effects is included in the Technical Appendix. Key findings include:

Federal spending would be reduced, on net, by $7.6 billion in 2014. This includes gross federal savings of $31.1 billion, offset by new costs of expanded coverage under Medicaid ($8.9 billion), federal premium and cost-sharing subsidies under the Exchange ($7.5 billion), and a reduction in Medicare premium receipts ($7.0 billion).

Seven million people age 65 or 66 at some point in 2014 would be affected by the policy change for one or more months. This number is equivalent to five million people affected for a full 12 months. Of that five million, we estimate 42 percent would turn to employer-sponsored plans for health insurance, either as active workers or retirees, 38 percent would enroll in the Exchange, and 20 percent would become covered under Medicaid.

Three-fourths of adults ages 65 and 66 affected by the proposal are projected to pay more out-of-pocket, on average, in premiums and cost sharing under their new source of coverage than they would have paid under Medicare. However, nearly one in four are projected to have lower out-of-pocket costs than they would have had if covered by Medicare, on average, mainly due to provisions in the health reform law that provide subsidies to the low-income population through Medicaid and the Exchange.

Premiums in the Exchange would rise for adults under age 65 by three percent (an additional $141 per enrollee in 2014), on average, due to the shift of older adults from Medicare into the pool of lives covered by the Exchange.

Medicare Part B premiums would increase by three percent in 2014, as the deferred enrollment of relatively healthy, lower-cost beneficiaries would raise the average cost across remaining beneficiaries.

In addition, costs to employers are projected to increase by $4.5 billion in 2014 and costs to states are expected to increase by $0.7 billion. In the aggregate, raising the age of eligibility to 67 in 2014 is projected to result in an estimated net increase of $5.6 billion in out-of-pocket costs for people who would otherwise have been covered by Medicare. This analysis underscores the importance of carefully assessing the distributional effects of various Medicare savings proposals to understand the likely impact on beneficiaries and other stakeholders.”

http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/8169.pdf

Thus, according to this study the Federal government would save on net $7.6 billion, the costs seniors would increase by $5.6 billion, the costs to private insurers would increase by $4.5 billion and the costs to states would increase by $0.7 billion annually.

In addition one has to factor in the aggregate cost of increased cost of premiums to adults under 65 on the insurance exchanges. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services estimates there will be 16.9 million people on the insurance exchanges in 2014 (See Table 2):

http://thehill.com/images/stories/whitepapers/pdf/oact%20memorandum%20on%20financial%20impact%20of%20ppaca%20as%20enacted.pdf

At $141 a person the increased premium cost comes to just under $2.4 billion.

Adding all this up yields an overall *increase* in healthcare costs of $5.6 billion assuming net Federal spending really does fall by $7.6 billion.

But even this is questionable. The evidence?

McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Health of previously uninsured adults after acquiring Medicare coverage. JAMA. 2007;298:2886-94.

“In this study, acquisition of Medicare coverage was associated with improved trends in self-reported health for previously uninsured adults, particularly those with cardiovascular disease or diabetes.”

http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/298/24/2886.full.pdf+html

McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Use of health services by previously uninsured Medicare beneficiaries. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:143-53.

“The costs of expanding health insurance coverage for uninsured adults before they reach the age of 65 years may be partially offset by subsequent reductions in health care use and spending for these adults after the age of 65, particularly if they have cardiovascular disease or diabetes before the age of 65 years.”

http://globalag.igc.org/health/us/2007/useofhealthservices.pdf

Thus it seems extremely silly to raise overall healthcare costs in pursuit of government savings that may or may not occur by raising the Medicare eligibility age.

Conservative Politicians where I live are pushing the balanced budget amendment. How would this impact our budget process and economy at large?

“voters want to believe they can get something for nothing, and the politicians are only too willing to promise exactly that.”. If we engaged in policies that raised technological growth…like a massive jobs program that built infrastructure (green or otherwise)…then we might make our long term problems a lot less problematic.

Some analysts (and Econbrowser commenters) maintain that the transmission mechanism for oil shocks is through financial or other markets. Thus, for example, increased oil prices manifest themselves in deteriorated current account balances for oil-importing countries, requiring additional short term debt. Greece, Ireland, Portugdal and Spain would all seem to have vulnerabilities on this front. Given existing weakness in their economies, this creates a debt crisis.

I have maintained for some time that we appear oil-constrained on re-employment. Our oil consumption is largely unchanged since the first month after the trough of the recession. For example, June 2011 oil consumption in the US is 150,000 barrels per day (0.8%) above June 2009 levels–and the recession troughed in May 2009. If employment remains depressed, then government revenues will remain depressed and expenditures elevated. Menzie has shown us in recent days just how acute the imbalance is.

In such a world, political compromise is all but impossible, because there is little overlap between the demands of political parties. This gap, in turn, manifests itself as protracted political conflict, for example, the whole debt ceiling drama we just lived through.

The proximate cause of the meltdown appears to be political, but the underlying cause is ultimately a shortage of cheap oil, by this way of thinking.

Income/money distribution and relative price levels have been the real problems. We need to reduce the debt burden on the middle incomes to increase confidence. Refinancing existing debts at treasury rates, or regulation to get borrowers out of paying interest on mortgage debt not currently supported by asset value would do wonders for moving us toward real, sustainable growth.

I agree with JDH that changes to entitlement programs for the aged are needed to restore fiscal balance. On average, we live longer: current tax rates assume a shorter life, so we need to reduce the amount of time beneficiaries collect these benefits (or raise the taxes to accommodate longer lives). But more important, we need to rethink the cost sharing: current tax rates assume lower health costs, so we need to increase the share of costs paid by beneficiaries (or raise the taxes to accommodate higher costs).

Bigger issue at stake: do we want a fiscal policy that redistributes income from younger Americans to older Americans? I am approaching old age, and would be willing to accept a shorter life (or fewer years collecting SocSec and Medicare) if that left my children and grandchildren with a better future.

It will be interesting to see if others, whose prior studies showed significant net federal savings with raising the age of Medicare eligibility, could duplicate the results of the KFF study with the more recent 2010 health reform law provisions.

We were in dire straits after Carter and we got out of it in style (and won the Cold War to boot). We will get out of the Obama mess, too. All we need is leadership and a bit of confidence.

Remember, Rich, the way we got out of the Carter mess was that Volcker rasied interest rates, and global oil consumption fell by 6 mbpd in the following four years (’79-’83). Meanwhile, Saudi was maintaining high prices, and this brought on 7 mbpd of new capacity in the same period (’79-’83). Thus, by 1983, we had 13 mbpd of spare capacity of 54 mbpd of consumption–a 26% supply overhang.

This overhand took nearly twenty years to absorb, a period now known as “The Great Moderation”.

Right now, the situation is just the opposite: China’s demand growth is relentless, the oil supply is up only 2% in six years, and we’re back in an oil shock again, just three years after the last one.

So, we need to get more oil–and hopefully the shale oils and Africa offshore will prove the North Sea and Gulf of Mexico of this generation. But for the moment, we have to expect a rocky ride for some time to come.

Instead of raising the retirement age (again) for Social Security why not raise the FICA tax base? Is it not true that the longer life spans are concentrated in the upper income group? As for Medicare what real benefit is there to raising the eligibility age when somewhere about half of total Medicare expenditures occur in the last year or two of life? How about openly discussing some form of rational rationing? Finally, if the Bush wars and the Bush tax cuts and the Bush drug benefit giveaway had been funded, we wud not be in this pickle!

I disagree that the drama was Congresses doing, rather it was the Administration that demanded a long term debt increase that would result in the largest debt limit increase in history. Opposition to a debt limit increase for a smaller amount and period would have easily sailed through Congress, that was essentially what most Republicans supported. It was the larger increase that caused the drama.

Initial analysis good, then you stray. Soc sec and medcare have are not the deficit problem. And the problem is not something for nothingism. The problem is the banks, defense firms, and health providers who are looting the public for triliions. We found $20 triliion to provide the banks for free. And found $4 trillion for the wars. Not to mention the trillions we found to lower wealth taxes to its lowesr point in decades.

Good point though about government spending, right wing propaganda has got people thinking of it as if 100% of is buried in a hole or burnt. Wherein much of the spending that the right loathes actually goes to everyday people mostly us citizens

Re rich. Indeed we got out of the doldrums after carter… Through stimulative deficit spending at massive levels!

Professor,

To address each of your Problems:

1. The first problem– finding a way to meet the government’s immediate spending commitments– was entirely a monster of Congress’s own creation.

It is a monster of Congress’s own creation but it started long before they lost the ability to meet spending commitments.

I have no doubt that most Congressmen believed the Keynesian solution would pull them through. They could tax the people and increase spending (consumption) and growth would provide for Congress’s largess. When the growth did not materialize congress shifted to deficits and just a little more Keynesianism.

The deficit had to be financed so the Treasury was given the power to borrow to cover the deficit. But this was politically risky so to pretend to be fiscally responsible Congress clothed Treasury borrowing in a façade called the debt ceiling. Congress still believed that spending (consumption) would create growth to cover their largess. But Treasury borrowing kept running into that pesky debt ceiling.

In stepped the Federal Reserve. Demand side inflation, Keynes suggested it to deal with union wage increases and Friedman told us it would have prevented the Great Depression, would save the day. The FED cranked up its purchases of Treasury debt such that in 2009 the FED borrowed 80% pumping massive amounts of money into the economy. Then they all sat back and waited for the inflation they knew would wipe out the debt. But the inflation did not come. Bank reserves exploded as real estate exploded and suddenly the transmission mechanisms broke down. They looked toward Keynes but his solution of government spending was the problem. Bernanke looked toward his promise to Milton Friedman to engage in monetary expansion but that was also the problem. The problem simply could not be its own solution; massive debt cannot be cured with more massive debt.

Today Keynes has run his course finding a dead end. So other voices shout. The new austerity-Spartans expose the Keynesian fallacy to anyone who will listen. Into the great vacuum stepped the austerity-Spartans. And that brings us to your second and third problems, because you cannot be solved one without the other.

2. The second problem– getting the unemployed back to work and

3.

Keynesianism created problems the greatest being unemployment. You express it well when you write, “Reducing government spending is taking away somebody’s income, namely, that of the government employee, contractor, or recipient of transfer payments” and the austerity-Spartans have offered no solution to this problem except pain. They stand strong and proclaim “no pain, no gain,” but the people have already suffered pain for no gain.

You also make the valid point, “…we will soon need to start making exactly those cuts. But the time to do so is when there are private sector jobs available to pick up the slack. If we try slashing the 2012 budget, it will just add more people to the current swollen unemployment rolls. But that begs the question. If private sector employment does not pick up can we afford to sit on our deficits?

What no one is talking is generating growth with proven techniques. We must increase the private sector if we want to increase private sector jobs. That means:

Lower taxes to 25%

Kill the Dodd-Frank act

Kill Sarbanes-Oxley act

This will immediately allow the private sector to expand and increase employment.

Then:

Kill Obamacare

Restructure Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid to include private sector solutions also increasing private sector employment.

Sell all the assets of Fannie Mae and Freddie to the private sector also increasing private sector employment.

We need growth not wasteful monetary expansion or destructive austerity.

Jim, Do you have a handle on what “current baseline” means in the debt deal legislation? For example, are the so-called Bush tax cuts and their expiration. If the super committee extends them would that count against debt reduction as defined by the bill? I’ve seen various claims, some of it muddied by partisan spin, some of it simply muddy.

Is it 1937 or have we come to the end of Reganism with its two prong approach; lower taxes and deregulation. After 30 years, both have reached the point where the incremental benefit is less than the incremental cost.

What interests me is the confidence that various commenters have that what is needed to restore the economy to its former glory is….

Perhaps anything that attacks the problem also has negative side effects and we have to decide which side effects are worth which benefits. It is a bit like the choices a man with prostate cancer faces.

While Prof. Hamilton may be right, looking only at the immediate effect that reductions in federal spending have on the economy, there are other risks for policy makers to consider. Failure to institute meaningful deficit reduction now puts the US is at risk of higher interest rates through a credit downgrade. Ratings agencies are not prone to trust politicians who follow Prof. Hamilton’s advice to borrow and spend now and impose austerity when the economy is creating jobs. “Lord make me virtuous, just not today.” So again we may simply have no good choices.

Perhaps the more prudent course is to take our austerity medicine in steady increments starting now, knowing that each ratchet down is going to slow short term growth. And in fact the current political configuration is producing precisely this effect, in that big cuts proposed in the House get diluted by the Senate and the President and the moderately bigger cuts are postponed.

I take issue with Prof. Hamilton’s complaint about the way in which the stand was taken. The spending decisions he mentions were made last year when the current phalanx of budget cutters had not been sworn in. There was no regular budget, in overt violation of the Budget Act, so the whole appropriations process was illegal to begin with.

Elections are about changing policy directions. 2010 was a wave election, so of course the new legislators would take the first opportunity that presented itself to change direction. Prof. Mamilton may not like the fact that the new House did not respect the lame duck House’s appropriations, but on the other hand, are the illegal actions of a prior Congress worth respecting?

John B. Chilton: Let me outsource that to Keith Hennessey.

Professor Hamilton-

I agree that Keith Hennessey is a very useful source. His recent podcast with Russ Roberts about the federal budget at econtalk is very educational.

Thanks, JDH. I’d read Keith’s followup to his post. I found the followup confusing relative to the link you point to (which I now have read with more care).

The followup for those interested,

http://keithhennessey.com/2011/08/02/can-the-joint-committee-get-credit-for-raising-tax-rates/

AS, I would disagree with much of the premise of the article. While the war did enforce thrift on one front, it was also a massive spending and employment project on the other. Unemployment went overnight from 15% into the low single-digits, creating a lot of income where none existed before. Secondly, there wasn’t much to spend that income one, and the war helped enforce a sense of sacrifice for the greater good which CLEARLY does not exist today. Part of it was ‘financial repression’, encouraging savers to save money via war bonds, essentially enforcing government bond purchases at low interest rates, but because of the war people were only too happy to do so.

As for the anti-keynesian-ness of the policy, he states that “a shrinking civilian work force and surging government demand created wage inflation of about 5% per year. Higher wages, plus about 20% more hours worked, generated a 65% increase in real (inflation adjusted) national disposable income between 1939 and 1945.” What could be more keynesian than that? The consumption was crowded out by the government demand, and the enforced savings for years did create a pent-up demand for civilian goods and services, fine. But that demand would not have happened without the government stepping in and creating literally millions of jobs overnight.

What we have today is more analagous to 1937, when output had almost reached pre-Depression levels but unemployment remained stubbornly high (14%) and Congress forced Roosevelt to balance the budget, creating a renewed recession and further delaying the recovery until 1941. And that’s what JH was writing about.

It has been a while since I read keynes, but my memory was that the end goal of stimulus was to restore “animal spirits”. Keynes writes:

In the end the end goal of stimulus was to change psychology.

I have seen virtually no real reflection on this passage given the Keynsian two step that has been proposed. To wit:

1. Increase sepnding now

2. Deal with long term budget problems later

This really isn’t a Keynsian program. The whole point of stimulus was to change expectations: but the budget back drop called into question from the very beginning the ability of the government to sustain fiscal stimulus. And in fact the Keynsians themselves argued that it was going to be temporary.

Make no mistake, I wish the stimulus package had been larger, but if I look at debt to GDP (the real measure of fiscal stimulus) we have run deficits almost twice as large as anything FDR ran before 1941. Arguing that the problem is that we didn’t pursue enough fiscal stimulus is right, but in historical terms the overall contribution by government was enourmous – certainly bigger than in 1935.

It is worth asking if Keynsians are being too clever by a half. To say we are going massively increase spending and then cut it later strikes me as a prescription that, given our political system, was ALWAYS unlikely. Given that fact we should be asking if a classic Keynsian program was ever going to be as effective as the theory taught us.

fladem-

Interesting that you raised the issue of “animal spirits”. Could not the animal spirits be awakened without all the spending? Perhaps by a congenial attitude toward enterprise. The current regime has done all it can to dampen “animal spirits” most likely because it has little experience in the private sector and is outright hostile to enterprise.

I think that Obama needs to reclaim the moral and political high-ground again by pledging that he will not sign an appropriations bill that does not have an appropriate increase in the debt ceiling attached to it.

Congress tied appropriations to raising the debt ceiling, he should tie raising the debt ceiling to appropriations. After all, the debt comes from the spending and taxing decisions made by Congress.

* Annual appropriations must contain sufficient room in the debt ceiling to cover that year’s appropriations, plus wiggle room for unexpectedly bad economic outcomes.

* Extensions of tax cuts that are not offset by revenue increases, must include an increase in the debt ceiling sufficient to cover all expected revenue shortfalls over the lifetime of the tax cut.

* Spending bills, even emergency spending bills, and continuing resolutions, will have to include an appropriate debt ceiling extension.

I would rather see a government shutdown because of lack of spending authorization than ever have the full faith and credit of the U.S. Treasury called into question again.

I think we’ve long past the time for Keynsian stimulus (not sure it was ever really appropriate, this was a structural problem). 4 years since the recession started (I believe it used to be dated the last quarter of 2007).

I see benefit from temporary tax cuts, so long as debt stays cheap (they should be very temporary). While tax cuts won’t increase investment, they will help repair balance sheets which is vital for consumer confidence and long term growth. Our focus on spending, and the short term, has been a horrible, horrible mistake.

When you have used up all of your resources and you insist on spending more, perhaps it would be wise to insist that something more than “the Chinese will lend us more money” is an appropriate request.

How about requiring that each new spending bill have a specifically identified source of revenue to cover the proposed spending. How many congressmen would attach their names to a bill that pins them down fiscally? That’s rhetorical, of course.

The computer algorithms are kicking in all ready I see and the market is rising again. Then it will fall a bit more, then it will rise, then it will fall, etc.. Blankfein thanks god for computers and mathematicians every day as he steadily if unspectacularly grinds out profits even in a collapsing market. I hope no one here thinks that human beings are involved in any of this theatre?

How is getting corporations and wealthy citizens to pay a fair share to support the society they benefit so greatly from a bad idea?

How can the so called TEA party be so obstinate?

Day to day fluctuation in the S&P is just noise. The long run trend is that the S&P has lost ground to inflation for over a decade now, and is on track to lose ground to inflation for another decade. Printing too much credit/debt has misallocated capital into unproductive venues. Debt contracted for unproductive purposes cannot be repaid, and bad debt is now slowing down the economy.

“It’s not clear that raising the age for Medicare elibility would reduce costs. As it is, many people already put off medical procedures until after Medicare kicks in. Raising the eligibility age would probably make this problem even worse. There’s no question that rising Medicare costs is the major long run debt driver, but to fix Medicare we need to fix healthcare costs in general. Shifting costs isn’t the answer. I would prefer that Medicare start announcing what procedures it will not cover rather than just delay coverage.”

It is not real clear that the average medical procedure provides any benefit whatsoever. Okay, this is not the most well researched area, but what little evidence we have (the famous RAND study from the ’70s, the amazingly bad death rate due to medical procedures, the fact that other countries spend much less per person and have similar health outcomes) puts our entire concept of “health insurance” into question.

I agree if would be best if we would just say what procedures Medicare won’t cover anymore, because costs exceed benefits. But I personally think that is a political non-starter. Better to just not have the Feds spend the money in the first place by not covering people. It might be inferior (yes, some people are going to postpone procedures, and some of those procedures will be beneficial), but it is more doable politically.

Market is down over 200 again today. How do you spell ‘double dip?’

Not double dip. Second peak oil recession.

“Second peak oil recession.”

“It’s all Bush’s fault… still… for years to come… as long as Obama is president.”

Two dumb theories brought together in one place, at last!

Here’s my diagnosis and prescription:

Diagnosis:

1. Too much money has concentrated in the hands of investors, due to increased bargaining power (unions dying, outsourcing, etc.) vis a vis workers.

2. This has caused too much money to be diverted away from consumption (which creates demand for goods and services and therefore employs people) toward asset trading (which inflates asset values and enriches the financial sector, but doesn’t create anywhere near as much demand for goods and services). Not to mention that it weakens democracy, corrupts government, etc. etc.

Prescription:

1. Restore tax rates as they were when Reagan left office (as you may recall, there were much higher taxes on higher incomes and capital gains at that time than now).

2. This will magically reduce the deficit to a very unscary level (maybe even create a surplus) using money from people who don’t create much aggregate demand for goods and services.

3. Take the additional cash flowing into the government to invest at least a couple of trillion dollars per year in infrastructure, including green energy and energy conservation projects that will pay for themselves through higher efficiency.

4. At the same time, tackle outsourcing with a tax policy that specifically targets sale of goods and services that are made with cheap foreign labor, so the cost to consumers is equalized.

5. And finally, reform labor relations laws to strengthen collective bargaining in one way, but weaken it in another. Strengthen, by requiring collective bargaining on wages and benefits for ALL firms. Weaken, by prohibiting any contract that reduces an employer’s right to terminate at will (subject, of course, to the standard antidiscrimination laws, including on the basis of union activity).

I’m confident I’ll never live to see any of this happen, but if you really think through each of these points, I think you’ll have to agree it would change the economic mix in some interesting directions.