On Friday, Standard & Poor’s, one of the three main credit rating agencies, downgraded U.S. Treasury debt from AAA to AA+, citing doubts about the effectiveness, stability, and predictability of American policymaking and political institutions in being able to deal with the rising debt burden by the middle of the decade. It’s been a wild ride for equity and commodity markets ever since.

Somewhat incredibly, Standard & Poor’s made a $2 trillion error in their calculation of future U.S. deficits. The other two major credit rating agencies, Moody’s and Fitch reaffirmed that they will be maintaining their AAA ratings. And Paul Krugman is among those questioning how an agency that had given AAA ratings to trillions of dollars of questionable mortgage-backed securities could now decide that U.S. debt had become more risky.

Still, the fundamental unease that many of us have been feeling about the U.S.’s long-term fiscal challenges could only have increased watching events in Washington over the last few weeks. I would have hoped that both parties could agree that, whatever differences we may have, the country is willing to bear whatever burdens are necessary to honor existing debt commitments. The erosion of that hope is part of what gives the decision by S&P some personal sting.

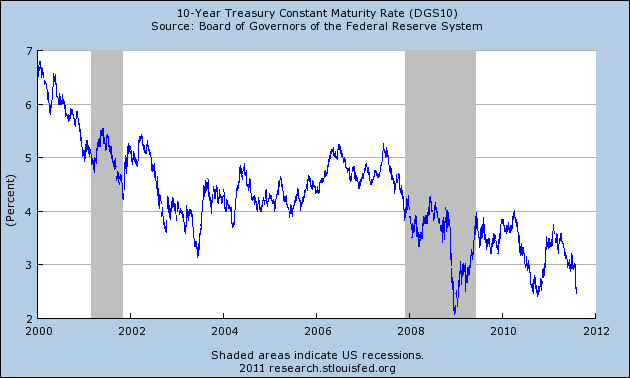

If this were all to be taken at face-value– if a rational, objective observer now sees less certainty of timely payment of interest and principal on U.S. Treasury obligations– the response should have been an increase in yields on Treasuries relative to other, supposedly safer obligations. But, as Krugman also notes, we observed exactly the opposite. The yield on 10-year Treasuries fell 18 basis points on Monday to 2.40%, and is down 61 basis points from July 27. Investors are buying 30-year Treasuries yielding 3.68%, down from 3.82% on Friday and 4.29% on July 27. S&P may be concerned about prospects for U.S. default, but the market seems not to be.

|

Notwithstanding, the dramatic plunge in equity and commodity prices seems likely to have been related to the downgrade. Tim Duy suggests some reasons:

Should the downgrade have significant economic consequences? I fear the answer is yes. First, if you believe confidence is important, that confidence has surely been shaken, as evidenced by wild ride of financial markets. Second, the political response could be a full-court press for more fiscal austerity. Finally, we don’t completely know the knock-off effects on the rest of the financial system.

Heightened uncertainty– and that’s what we have here– brings

a flight to safety, ironically, to U.S. Treasuries, which can wreak havoc for everybody else.

Many observers also seemed to be hoping that these events might trigger a new round of large-scale asset purchases from the Federal Reserve. The direct effects we might hope for from these would be to depress long-term yields even further. It would of course be odd to claim that the main problem is that these yields haven’t fallen enough over the last two weeks. Instead, the concern must be whether inflation expectations are coming down again with deteriorating economic conditions. The break-even inflation rate (10-year nominal minus 10-year TIPS) fell from 2.45% July 27 to 2.20% on Monday. There is room for the Fed to be reminding everyone they’re not going to tolerate deflation.

Instead of more large-scale asset purchases, the FOMC settled instead on replacing its previous boilerplate commitment to maintain an exceptionally low federal funds rate “for an extended period” with a new, more concrete statement that rates will remain exceptionally low “at least through mid-2013”. And this change in wording was approved over the objections of 3 of the current 10 voting members of the FOMC. If we do see more deflationary pressures developing, I would expect the Fed to embark on QE3, but until that happens, this may be all we’re going to get.

While the U.S. debt downgrade is one of the dramatic events that began this week, I continue to stress that other developments are more critical. Although the security of U.S. sovereign debt is not really yet in question, the same is not true of peripheral Europe. With the spread of those concerns to the major economies of Spain and Italy, we have reached a very troubling situation there. The worry is that banks may suffer significant losses on some European sovereign debt. Fears about that may freeze lending more broadly, for a possible replay of the disastrous events of the fall of 2008.

Even in the absence of those developments, there is no question that the U.S. economy has been weakening considerably. JP Morgan reminds us that U.S. stock prices declined 15% or more within the space of 4 months on 30 separate occasions since 1939, and only half of those were associated with an economic recession.

But watching this morning’s stock market, it’s hard to be confident that this time is going to turn out in the favorable half of the distribution.

Yes, looks like greater than 50% chance of recession.

Better be, or else it’s crow sandwich for me!

The Q3 survey of professional forecasters is to be released Friday morning; it will be interesting to see their estimate of the probabilities of a contraction in real GDP.

I just don’t see where the growth comes from in the next few years. It doesn’t appear that it will be driven by easy consumer credit or by government spending. This leaves business to drive the bulk of the growth. However, the dilemma is that business won’t spend and hire until demand appears on the horizon, and consumers won’t spend until unemployment falls and workers are secure in their jobs.

Firms realize that temporary fiscal stimulus on the demand side won’t translate into a permanent recovery. Government payroll and capex incentives might help a bit, but most firms won’t roll out huge cap ex projects until a recovery has some momentum.

It seems the only solution is permanent change to the tax system that incent business and consumers today, while being backloaded with deficit reduction measures for the future.

Hello Japan!

I’m not so sure I would call it a “$2 trillion error.” As John Taylor and others have argued, the difference of opinion lies in whether you assume government spending grows at the rate of nominal GDP or at a lower rate as assumed by the CBO. What the downgrade means in light of 10-year treasuries at record lows is a legitimate question, however. Moody’s may still downgrade us, as we are “under review” in their parlance; and Fitch may follow suit after their analysis wraps up at the end of the month.

Professor,

How do you understand the following FOMC statement?

“economic conditions … are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through mid-2013.”

Do you believe it means:

a) FED envisions weak economic conditions are likely to persist for at least 2 years?

b) Starting yesterday, FED is less likely to fight inflationary pressures for at least 2 years?

c) IF economic conditions are weak and inflation is low for the next 2 years, then the federal funds rate will remain exceptionally low. Since this is already widely understood to be the case, there appears to be no change in action plan for the FED.

Thanks

b turnbull: Thanks for making it a multiple choice. I’ll go with (b), though I think it also communicates some judgment call that the Fed feels it doesn’t have to worry enough about inflation for the next 2 years to want to start raising interest rates before that.

We need energy to improve the economy. So we have to drill our way out of it. It can be done.

By the way, we’re seeing incredible levels of client inquiry in our business right now. Very typical of late stage business cycle expansions–without the general economic expansion. Again, entirely consistent with an oil shock.

The Treasury issues notes, bills, and bonds to cover the current deficit and roll over past deficits. The Federal Reserve keeps interest rates low and tries to expand the money supply by buying US debt from banks, writing a check to the banks. However, the banks aren’t lending this money out so it can get into the economy, be deposited in other banks, and create money via fractional reserve banking. It’s sitting in excess reserves. The monetary base has increased but money velocity has dropped, and we’re suffering general slack demand and deflation except for supply shocks from droughts, war, earthquakes, etc. Is this about right?

Now doesn’t the Treasury also have power to create money, as it does when it prints the $20 bill in my wallet? What if the Treasury paid some of America’s bills with new fiat money? Instead of sitting as bank excess reserves, it would go straight into the consumer economy. Of course we don’t want to overdo it and turn into the Weimar Republic or Zimbabwe with hyperinflation due to debasement of the currency. But a little inflation would cure a lot of the overhanging debt problems in this economy. Any flaw in my logic here?

I’d say the Fed statement is them signaling the markets that they will act as necessary. If you note the dissenting 3 votes were over the language specifically referring to 2013 instead of the more typical reference to a very long time. The 2013 reference must be intended to push at long term rates, which it has, as noted.

But I think the markets are also pricing the Fed’s posture. The Fed has been acting through this period and I’d say the markets are reading this signal as saying the Fed will continue to act, meaning that if conditions deteriorate they will do more QE and the like. There is a hint of promise in there, one that leaves open if, when and how much. That’s how the Fed typically speaks. The specific date is very unusual.

My 2 cents, since everyone guesses at what they mean.

There are other factors at work here. While the debt deal appears to have succeeded in lowering the risk of a U.S. government default, the level of default risk is still elevated, which means that long-term interest rates are still higher than they would otherwise be. That’s robbing the potential for higher GDP growth rates, which is what investors are now adjusting to accommodate.

The expectation of near-recessionary or recessionary growth rates, in turn, is pushing Treasury yields downward. If anything, the markets are acting as if they are anticipating deflationary conditions to develop.

The WSJ math is a bit off, i would say – they argue 33% chance of a recession.

But thats because 7 of the declines came after the recession started.

I would say, since recessions are post-dated after a considerable time, given the level of downward revisions we already saw, and the weak sub-stall-speed in the 1st half, we cannot say whether the recession has started or not. I would count those and make it a 50% chance of recession.

One thing is for sure: whether it is 33% or 50%, that is far greater odds than the fed model predicted in june. given the level of UE and the likelihood that headline inflation is about to become deflation thanks to commodities prices, the fed is already 6-9 months behind the curve. now that we have to wait two weeks to hear the jackson hole speech, the pain will only get worse increasing the odds of a pullback in investment and a recession.

Ironman While the debt deal appears to have succeeded in lowering the risk of a U.S. government default,

How did you come to this conclusion? S&P’s statement clearly implies exactly the opposite. S&P’s concern was that the debt deal proved politically useful for the Republicans. Boehner said that he got 98% of what he wanted and McConnell said that it means the debt hostage taking tactic would be the new template for future debt ceiling extortions…oops, I mean negotiations. McConnell’s takeaway wasn’t that politicians shouldn’t be playing with matches when standing around gasoline, but that “ransoming the hostage” worked politically. Far from making the default risk less likely the deal made future default risk much greater.

Steve Kopits If you believe this recession is following the standard oil shock recession, then presumably you are telling your clients that it should follow the standard oil shock recovery. I mean that’s the only consistent position you should be taking if you genuinely believe this is just another oil shock recession. But my bet is that you’re not telling your clients to expect an oil shock recovery. Am I right?

Prof. Hamilton,

The Monetary base is 35% higher than 12 months earlier, & did not decelerate in the least thru 27 July, to wit, a month after QE2 supposedly ended. Therefore, it makes no sense whatsoever to conclude anything from the falling 10 yr interest rate.

In my view, what S&P did was at least reasonable. It is inconceivable that the US will pay its explicit debt & unfunded liabilities in real 2011 value $s. It is a virtual certainty that the US will inflate away the value of these obligations by “printing” $s.

S&P is actually more sanguine than I am for it is said that they would not have downgraded had the House’s ‘Cut,Cap,& Balance’ bill been passed by the Senate.

Interest rates fell as investors moved their money out of stocks, and into the safety of US treasuries.

AA+ is still a great rating. Investors do not expect default. But, the world economic outook is not as good today as it seemed to be a few weeks ago. The market has reacted to that. Our debt problems, and those of europe, are only a part of the changing outlook.

It’s really an argument about curve grading, isn’t it?

Right now, the US government is winning the least ugly contest, like a dunce graded against classmates who didn’t show up to the test.

I think Felix Salmon has a good explanation for the effect of declining yields on US Gov Bonds after the downgrade: http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2011/08/09/the-difference-between-sp-and-moodys/

In essence, S&P only makes a judgement on the probability of default (PD), whereas Moody’s makes a judgement on the expected loss (EL). In this regard, S&P might expect a higher PD without necessarilty implying a higher EL. Insofar as investors might still expect to be fully paid even in the case of a default, US Gov Bonds stay the safe haven although they were downgraded with regard to the PD.

Bryce: S&P is explicit that the basis for their domestic currency sovereign debt ratings (i.e. the one on which they just downgraded the US) does not take inflation into account. They are looking at pure default probabilities; they are not trying to predict real yields.

I suspect S&P is applying a PC narrative. The growing size if debt, future obligations, and size of government spending relative to private sector growth are Tue real problems.

I suggest that anyone who is interested in Ironman’s comments follow the links to his very interesting and analytical website.

Occam’s Razor would say the debt ceiling deal drove the market because the S&P downgrade came much later. So how can we judge the impact of the S&P downgrade? Since it was a downgrade of government securities, if it had any impact they should have shown a decline. As both Paul Krugman and JDH point out that did not happen. So again using Occam’s Razor, essentially actual investors pretty much ignored S&P. Only the pundits and media mush-minded think it really had much meaning. The key to where we are and were we are going is congress and the president and the prospects there are not very good.

We our problem is a debt and deficit problem. Will the agreement between the parties, congress and the president reduce the debt and deficit at the end of the year from what it is today? How about next year? Answer those questions and you have the answer to why the markets are falling.

SvN, thanks for the clarification. Seems odd in that either way the bondholders & “entitled” are being dealt with dishonestly.

Were bond-rating govt-imprimatured oligopoly being paid by bond purchasers, as they would in a free market, I bet they would be making a more inclusive & useful rating.

Bryce, instead of inflating away the obligations, we seem to be inflating away the discretionary income needed to pay them.

It is clear that since the arithmetic mistake did not alter the judgment, the real issue is the danger of default due to “political gridlock,” with leading politicians declaring that what happened this year will henceforth be the “new normal,” after 89 “clean” debt ceiling increases in the last 72 years.

Slugs –

Here’s a document I drafted this morning for possible distribution to our clients (at this time, this should be construed as my personal view only):

Recession Warning

Since April, in both in our public and client-specific presentations, we have cautioned about the risks of an oil shock-induced recession in the United States, and possibly more broadly in the OECD countries, by the end of summer. Historically, when crude oil consumption has exceeded 4% of GDP in the United States, the country has fallen into recession. Oil consumption has averaged 5.5% of GDP in recent months and reached 6% in April—levels well in excess of those traditionally associated with the onset of recession in the US. Further, JP Morgan has noted that stock price falls of the magnitude seen in early August have a 50% probability of preceding a recession. As such, probability of a recession would appear to be at least 50%, and allowing for an oil shock, the correlation is literally 100%. Thus, we advise our clients and industry participants to consider the risks of recession and contemplate mitigating strategies.

Historically, in oil shock recessions, US unemployment rises by four percentage points. Were this to hold in a coming recession, US headline unemployment might be expected to rise to 13%. In addition, oil shocks are associated with a deterioration in the federal government’s budget deficit, worsening by two percentage points historically, which would put the budget deficit in the range of 11% of GDP. We note that the historical record for the budget impact of oil shocks is limited, and no previous oil shocks were accompanied by either the fiscal or financial sector weakness we see today in the United States or Europe. Actual fiscal impact may therefore vary materially from that inferred from the historical record.

Given the negative reception of the US debt ceiling agreement by equity markets and ratings agencies, we believe there is a considerable chance that, in the event of a recession, the agreement will be revisited, with both material, short-term spending cuts and tax increases to be anticipated, very possibly during the worst of the recession. Such policy changes would appear to present a high risk of social unrest in the United States similar to that seen in Britain lately. Operators may wish to review their risk mitigation plans for operating facilities.

Were oil demand to fall in line with the 2008/2009 recession, global consumption might fall by approximately 4-5 mbpd, from 88.5 mbpd today to 83-84 mbpd. However, given the strength of demand in recent times, the fall could be perhaps a million or so barrels per day less. As we believe the ultimate cause of an impending recession would be an oil shock—the high price of oil—oil demand is likely to recover solidly after any downturn, much as we have seen since the last recession. Less than two years passed from the trough of oil demand in the last recession in May 2009 until the following oil shock beginning in April this year. We expect a similar pattern to hold in the future.

Thus, any downturn will represent an entry point for investors and companies seeking oil production or oil field services related acquisitions. Given the strong balance sheets of many of the companies in the industry, and given the wide-spread expectation of a return to high oil prices, investors should not anticipate bargain prices on the whole, but should at least hope for a come-down from recent lofty valuations. Thus, while we cautioned against acquiring assets after early spring of this year, a downturn would re-open the acquisition window and should encourage investors to ramp up screening and targeting activities, with an eye to locking in valuations, possibly in early 2012.

The US Treasury market is heavily influenced by stock market investors who use treasuries as a parking place for their money when they reduce their stock positions. As such, it can move up and down because of this, even overpowering the expeced movement from a theoretical analysis of treasury bonds.

The theoretical expectation expressed by Paul Krugman and other academics above was made without sufficient consideration of the complex interaction of the various securities markets.

I think that the impetus for the market correction was the political change in Washington as a result of the debt limit negotiations. From my perspective, I see the Obama administration agreeing that austerity and fiscal discipline is necessary. Consequently, the outlook for continued $1.4 Trillion deficits is quickly evaporating… If eliminated, deficit spending would create a 10% hole in GDP… Whatever the level of discipline eventually haggled, the result will be a precipitous drop in economic activity. An outcome not lost on professional institutional investors or an educated retail investor. Pinning market volatility on the S&P treasury rating is what I would expect from ABC news.

Dr. Hamilton suggests that sovereign debt default in peripheral Europe, might result in a credit freeze like we experienced in 2008. That would imply that interest rate and credit default markets have not been regulated and that many bank liabilities have not been disclosed to either regulators or the public. Isn’t it time to make over the counter unreported derivative contracts unenforceable in the courts?

Steven, mind if I reproduce your comment with attribution on Facebook?

Steven,

I think your warning of recession is valid, though over zealous. Unemployment is already high, this will limit the likely decline. Most jobs now are either high marginal productivity or exist because of government fiat. The decline will be significantly dampened (maybe near zero).

I would welcome a reconsideration of our budget, but I don’t think there is worry here. Our short term spending is pretty well set for at least a year.

We don’t have the pop density or social unrest to get us anywhere near Europe. We could get there if there isn’t some sort of debt forgiveness or broad interest rate relief for bubble debt, but were still not there.

Your closing paragraph is dead nuts on. A (near) recession should force us to face reality.

As I expected, the U.S. downgrade by S&P was going to be a lot worse for the stock market than for treasuries. This came as a major surprise for most people as it is counter intuitive. The reason being is that it was not so much a loss in confidence in the ability of the U.S. Government to pay its debts as it was a signal that the free spending ways of the last 50 years is ending. History shows that sovereign downgrades spark action in governments to tighten their belts and cut budgets. Less spending, whether it be in employment, infrastructure or social services including Social Security and Medicare means less aggregate demand in an economy and thus less revenue and profit.

The debt crisis in Europe and the US is of great concern to the economic outlook and profit expectations. With or without the S&P downgrade, the equity markets were headed for a correction on this declining confidence.

The downgrade by S&P added to the general public’s awareness of the problems that investors were already worrying about.

Personally, I did some selling a few weeks ago, and then bought stocks on Monday, Tuesday and Wedsnesday of this week. I think this will blow over, and stocks will be up nicely by spring.

Thank you Steven Kopits for sharing.

I place little probability of a US recession. Stagnation is more likely. By ‘stagnation’, I mean low real aggregate growth, accompanied by zero per capita growth and modest inflation rates. Oil prices and other commodity prices will remain high.

1. There was a huge revision down in GDP concurrent with that downgrade

2. The downgrade was well telegraphed in advance

3. Italy started to have major funding issues as well.

4. cetris was not peribus