And Generalissimo Francisco Franco is still dead (with apologies to the under 35 set).

Since in the U.S. we are currently embarking upon a program of reducing fiscal stimulus, it seems useful to examine whether this action would result in rapid economic growth as some have predicted. The UK is at the forefront of conducting this fiscal experiment.

Figure 1: UK real GDP (in Ch.2006 pounds) growth q/q SAAR (blue) and 4 qtr (red), both calculated in log differences. Note: reported at annualized rates, unlike in the UK official statistics. Source: FREDII and ONS and author’s calculations.

The lackluster growth of 0.2% q/q (0.8% q/q annualized) reported on July 26th is hardly a resounding vindication of the approach. The economic analysis accompanying the release noted:

There were a number of special factors which may have affected economic activity in the second quarter, including the additional bank holiday for the royal wedding, the after-effects of the Japanese earthquake and tsunami, and the unusually warm weather in April and May. Following standard practice, no adjustments have been made to the published data to remove the effect of this (non-recurring) bank holiday.

It is not possible to state precisely what the net overall impact of these special events might have been. Estimates, using standard statistical techniques, have been constructed for what could have happened in April, May and June for each of the main aggregates in the service and production sectors, if the special events outlined above had not occurred. This has then been compared with the actual estimates that we produced. The results of this analysis indicate that Q2’s special events may have had a net downward impact on Q2 2011 GDP of:

0.4 per cent in the services sector

0.1 per cent in the production sector

These estimates must be regarded as broad brush and illustrative. There can be no certainty as to the impact of the special events and there may be other factors at play.

So it might be that the underlying strength of the economy in 2011Q2 is 0.5 ppts higher q/q (or 2 ppts on an annualized basis). However, even taking that into account, prospects going forward are not too promising. Before the recent turmoil in financial markets, growth forecasts were being marked down. From the FT

The UK is unlikely to hit [the government’s] target of 1.7 per cent growth this year, according to the head of the country’s independent budgetary watchdog, raising further doubts over the government’s deficit reduction plans.

Robert Chote, chairman of the Office of Budget Responsibility, said in an interview with the Independent that “there aren’t many people” expecting annual growth to reach the 1.7 per cent growth forecast made by chancellor George Osborne in March, and cautioned that current growth could be “relatively weak”.

Mr Osborne is already under pressure to accelerate tax cuts and step up supply-side reforms following meagre growth of just 0.2 per cent in the second quarter. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research on Wednesday downgraded its growth estimate for 2011 from 1.4 per cent to 1.3 per cent, arguing that subdued domestic demand, caused by low wage growth and contractions in consumer spending, would “hinder any meaningful recovery” this year.

The Treasury’s own comparison of forecasters’ estimates shows that the mean outlook in July was 1.4 per cent, down from 1.5 per cent in June.

The IMF’s Article IV mission to the U.K., completed in early June, already had less optimistic forecasts, at 1.5% q4/q4. That was the same as the OECD’s forecast, released at the end of May. Presumably, those too have been marked down.

Then yesterday, the Bank of England released its inflation forecast. In it, it reduced its 2011 growth forecast from 1.9% to 1.7%. This might be a bit optimistic. As the report notes, the outcomes have been a bit lower than the central tendency of forecasts, as shown in Chart 1.

Chart 1 from Bank of England, “Inflation Report,” (August 2011).

There is an interesting discussion of how revisions fit into this outcome on pages 22-23 of the report. One possibility is future data revisions would push up GDP growth.

On a side note, I will observe a time series plot of UK consumption through 2011Q1 is pretty unsettling.

Labor Force Indicators

Employment growth appears to be tailing off as well. Chart 3.3 from the Report is below.

Chart 3.3 from Bank of England, “Inflation Report,” (August 2011).

It’s interesting to consider what government policy is doing in this regard. From page 26-27:

Increased LFS employment has been driven by the private

sector, where employment rose by around 540,000 over the

four quarters to Q1. In contrast, general government

employment fell by 125,000 over the same period (Chart 3.5).

According to Office for Budget Responsibility projections,

general government employment is expected to fall by around 400,000 over the next five years, although the majority of that

reduction occurs from financial year 2013/14 onward.

The government has reiterated its commitment to reducing expenditures on the police force by 20%.[0].

Some UK-based commentary from [Dillow/Stumbling and Mumbling], and [Tax Research UK]. Earlier posts on expansionary fiscal contractions: [1] [2]

And back in the United States

From WSJ’s “Ahead of the Tape”:

…the hit from spending cuts across all levels of government has already been a major drag on growth. Indeed, these declines shaved 0.7 percentage-points on average from gross domestic product growth in the first two quarters of 2011. Typically, that would be no disaster. Trouble is, this recovery has been unusually weak. So the government cutbacks effectively halved real GDP growth in the first half of 2011, leaving it at just 0.8% annualized.

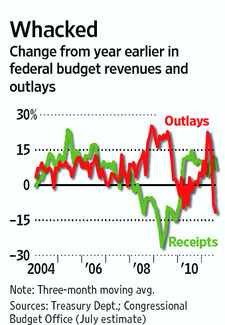

The pace of underlying growth is expected to pick up a bit in coming months. But so, too, is the pace of government spending cuts. A glimpse of this will come Wednesday with the release of July federal budget figures. These are expected to show a third month in a row of year-on-year declines in spending, or “outlays,” according to a preliminary analysis from the Congressional Budget Office. Their estimates show spending is down nearly 12% on average since May from a year earlier.

And the rate of fiscal retrenchment is only likely to grow. The debt-ceiling impasse underscores the degree to which Congress is unable to pass almost any legislation without agreeing on further cuts. That has already capped discretionary spending for fiscal year 2012, which begins October 1. Further cuts in 2013 and beyond will kick in if the so-called Congressional “super-committee” fails to come up with additional deficit-cutting measures by autumn.

The pressure to cut spending isn’t just internal. Standard & Poor’s just stripped the U.S. of its triple-A rating in part because cuts haven’t been deeper. Moody’s has indicated it may follow if costly stimulus measures like the Bush tax cuts don’t expire. Yet this casts further uncertainty on the growth outlook. The hit to first-quarter GDP next year could be as much as 1.5 percentage-points from government cutbacks alone if the payroll tax cut expires at year-end, notes Goldman Sachs.

Figure from , K. Evans, “Ahead of the Tape,” WSJ (August 10, 2011).

More discussion of the inapplicability of expansionary fiscal contractions to the United States in 2011 here.

So, brace yourself for a lot of macroeconomic uncertainty, and possibly large amounts of fiscal drag in FY 2013 (after all, the United States is a large, quasi-closed economy, even more than before at zero policy rates for an extended period, and the consequent big multipliers go both ways).

I would just take the Goldman Sachs note as a departure and propose that gov cuts coupled with already LEAN practices implemented by the private sector could be a very disruptive negative feedback loop that not even the 10 year breakeven inflation rate could pick up on.

Surely you are not suggesting we evaluate the effectiveness of the U.K.policy simply by looking at an outcome variable in isolation?

Jeff: Good point. From Walia, “United Kingdom Outlook Update: Gloomy Picture,” Roubini.com (June 2011) (sub. req.):

You can see the amount of fiscal contraction in the Roubini.com graph included in this post, which was note [1] in the post.

If you ignore government spending changes, how does growth compare?

Deficit spending changes?

Expansionary fiscal contraction may not happen for the U.K., but they might obtain a secondary goal of reducing debt across the economy. The BOE has been remarkably tolerant of inflation in the U.K. and while real GDP growth might be anemic, nomimal GDP growth is somewhat more robust. This nominal growth is reducing debt load as the gov’t tries to balance its budget.

Looking across the North Atlantic basin, very few economies have robust real growth. Perhaps at this point, the best strategy is to reduce debt, rather than pursue growth which seams to be eluding nearly every other economy?

I only had to read the title to know this was a Menzie Chinn post.

The point, dear Menzie, is that monetary policy and fiscal policy are impotent in our current situation.

Government spending did nothing in the past two years except reinforce inefficient resource allocation, prevent price adjustment, pick winners and losers, and reward the stupidest people in the room.

If we didn’t have trillions in debt, perhaps we could tread water a while longer with some not-so-stimulating expenditures. But states and the federal government spent $1.05 to $1.10 for every dollar collected in revenues during the boom. The federal, state, and local governments have made even more promises with dollars they don’t have and won’t have.

A long, slow, painful recovery is a fait accompli. The purpose of austerity is not to invigorate the economy, but to keep us from flushing resources down the toilet for our children. It’s to reduce the debt burden NOW while we have the highest bargaining power against all the moneyed interests whose rent seeking built this mountain of debt.

Public sentiment has NEVER been so high in my lifetime to roll back government at every level. If people get laid off rather than having wage adjustments, it’s because of labor unions, not those who wish to cut the budgets.

Contrary to brain-dead Keynesian dogma, the US will NOT suffer any huge consequences from prudent austerity measures by government. Government produces no income or wealth – it robs the private sector of income and wealth, hauling it away in a leaky bucket. The transfers and taxes are costly. When there are excess expenditures from government, we lose NOTHING by cutting them. We return the assets to productive use in markets where price discipline leads to more efficient outcomes.

I’ve seen CEOs cut costs in hard times. Firms and banks have voluntarily liquidated. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a government bureaucrat recommend cuts or elimination of their own departments for an insufficient return on taxpayer dollars.

Sadly, Mike thinks argument by assertion is an adequate answer to Menzie’s point. Mike claims no good has come of fiscal policy during the recession and after. Mike claims that the US won’t suffer from ill-timed fiscal contraction. Mike somehow fails to offer anything like evidence.

Simple GDP accounting shows how a reduction in the fiscal deficit is contractionary. When the market for productive resources is fairly tight, that contractionary influence can be overcome by freeing up resources for use in private endeavors. The market for productive resources is far from tight, leaving the clear implication that contractionary fiscal policy is contractionary for the overall economy. Mike has offered nothing to suggest that is untrue.

By the way, this – “So the government cutbacks effectively halved real GDP growth in the first half of 2011, leaving it at just 0.8% annualized” – is likely to prove too optimistic once revised GDP data are released. The big trade deficit in June probably means a downward revision to Q2 GDP, and so the drag from reduced government spending will have reduced growth by more than half in H1.

Mike:

‘Contrary to brain-dead Keynesian dogma’

This is a sure tell that Mike has not read even a biography of Keynes, much less Keynes himself.

‘Government produces no income or wealth – it robs the private sector of income and wealth, hauling it away in a leaky bucket.’

The truth is government makes it possible for the private sector to operate, and builds public works without which private agents could not exist in any competitive form. Mike doesn’t know this, but the ‘dollar here means no dollar there’ is a Say’s Law viewpoint which hasn’t held in economic reality since maybe the mid 18th century.

Contrary to Mike’s brain dead theories, imposing higher marginal income tax rates dislodges massive inert savings (which cause unemployment) thus allowing for investment increases (which create employment).

in the article it says the 20% reduction is achievable (in part) because there are 7000 officers in back office jobs, some of which can be cut (moved?) to “free them up” for the front line. Maybe I am mathematically challenged but how does that work – shuffling jobs from one area to another? “Front line” police generally make more so say you cut 10 “back office” jobs and and redeploy into 8 front line jobs that pay 25% more…no, thats breakeven, maybe 6 front line officers…but now those 6 officers generate more paperwork, and i have 10 fewer people to do the work that already existed… ooh i know, productivity! computers! oh wait, gotta put that in the budget. not to mention its more expensive to use the army as a guard (tanks use tons of oil!).

throw it all into the spreadsheet and goalseek for 20%….solving…

ooof my head hurts from trying to figure out ministerial math.

If “G” is part of GDP, then reducing G will reduce GDP, unless other components increase faster. That’s unlikely. Therefore, almost by definition, reducing government spending will reduce GDP.

However, that’s not the point. The point is that the US deficit is as a percent of GDP is among the top four tracked by The Economist. It is only one percentage point less than that of Greece. I think the markets have demonstrated their view that this deficit is unsustainable.

However, if you make spending cuts, then right now, you have to expect people in the street. The UK, Greece and Wisconsin experiences all suggest that.

“Thelma and Louise” is an American movie that ends with the two main characters committing suicide by driving off the edge of a cliff. I’ve often thought that this cinematic moment is an appropriate symbol for the actions of many developed OECD countries that are in effect borrowing money to maintain or increase current consumption. The central problem with this approach is that as my frequent co-author, Samuel Foucher, and I have repeatedly discussed, the supply of global net oil exports has been flat to declining since 2005, with “Chindia” taking an ever greater share of what is (net) exported globally. Chindia’s combined net oil imports, as a percentage of global net exports, rose from 11% in 2005 to 17% in 2009.

At precisely the point in time that developed countries should be taking steps to discourage consumption, many OECD countries, especially the US, are doing the exact opposite, by effectively encouraging consumption. Therefore, the actions by many OECD countries aimed at encouraging consumption in the face of declining available global net oil exports can be seen as the OECD “Thelma & Louise” Race to the Edge of the Cliff.

I suppose that the “winner” could be viewed as the first country that can no longer borrow enough money, at affordable rates, to maintain their current lifestyle. So, based on this metric, Greece would appear to be currently in the lead, with many other countries not far behind them.”

Great comment Mike,

State-employed economists generally don’t understand that economics requires profitable production and economization of resources. They like to imagine themselves as enlightened central planners, spending other peoples’ money.

Expansionary fiscal contraction may not happen for the U.K., but they might obtain a secondary goal of reducing debt across the economy. The BOE has been remarkably tolerant of inflation in the U.K. and while real GDP growth might be anemic, nomimal GDP growth is somewhat more robust. This nominal growth is reducing debt load as the gov’t tries to balance its budget.

Looking across the North Atlantic basin, very few economies have robust real growth. Perhaps at this point, the best strategy is to reduce debt, rather than pursue growth which seams to be eluding nearly every other economy?

Menzie,

You are absolutely correct. If a government that has taken over much of the private sector suddenly begins to cut spending and services the economy will decline. If this is combined with an increase in taxes as the UK has also done (increasing the VAT from 17.5% to 20%) the portion of the economy supported by the private sector is also hit.

The policies of the UK have been the worst of both possible worlds. They have taken the worst parts of the Republican ideas and added the worst part of the Democrat ideas and implemented both.

The right policies are to de-nationalize as much as possible and turn it back to the private sector where market discipline can improve products and services as well as properly allocate factors of production and improve effency. Additionally government savings from these reductions should be returned to the private sector in the form or tax cuts. This gives us the best of both worlds, reduced government spending and taxes and stimulation of the private sector leading to higher revenues and increased employment.

Good post.

There are at least 2 levels of issue. One is the measurable effects of policy and another is the meaning for the models that justify the ideas.

A major justification has been the idea that increased confidence would have an effect on supply. To drastically simplify for commenters – some of whom repeatedly show they can barely comprehend – Ricardian models are rooted in supply. We hear this argument in the US. Versions floated, often by Chicago related economists and certainly by Greenspan, include that uncertainty over future tax hikes prevents business from having confidence (despite surveys that show it’s sales worries), and that reducing debt will provide the confidence necessary for suppliers to produce more goods, hire more people, etc. The latter is directly the argument made in Britain.

One can say the confidence argument is not working. At all. If indeed inflation turns out to be the godsend, then that actually argues against the model because those who back the confidence model tend to be strongly against inflation (in part because it erodes confidence in their models).

When I hear this argument, made recently by Cochrane for example, I wonder how far a person can go to justify intellectual pre-conceptions in the face of evidence. Where is the evidence that this confidence idea is meaningful? The best I’ve heard is a strange argument that distorts the government’s actions in The Great Depression from stimulating demand – by such things as massive work programs – into one that created confidence for suppliers. That seems somewhat perverse, especially in light of the lack of results from austerity experiments in Europe. It certainly hasn’t worked in a country like Latvia, which is much further along; their GDP, really every measure of well being, is drastically lower.

Menzie-

So I am guessing that if a plan like the Ryan plan is put in effect, with a gradual shift in Medicare/Medicaid to a defined contribution approach, and lower tax rates and a broader base, and restraints on government spending, you think the economy will not perform well. I think it will.

Menzie,

I didn’t bother registering for the Roubini article, but how do you reconcile their “review of the lit” compare with Ilzetzki’s finding of zero to negative multipliers for floating, open and highly indebted countries?

Jeff: AS we’ve had this exchange before on the Ilzetzki et al. findings, let be briefly repeat myself. Ilzetzki et al. found larger multipliers for large, and closed (using exports+imports to GDP), economies, and those on fixed rates. They attributed the latter findings to the constant interest rate that accompanies fixed rates. So, I count the US as having larger multipliers. In addition, the US is slightly over the break off for “highly indebted”. So putting together these conditions, I count multipliers as being large for the US. So I don’t have to repeat again, please refer to our last debate on this for more.

I truly don’t understand the appeal of Ryan. His plan doesn’t reduce the deficit in the first 10 years. (I think one of the idiot defenders in an earlier comment section referred to 30 year projections.) He reduces taxes for the rich to shift costs to the sick and poor and their families. His revenue assertions are just that: assertions without a shred of reality attached. He lists nothing but a target for revenue and has refused to have the versions that spell out any detail examined by CBO. It amazes me that people quote the revenue numbers when CBO says bluntly they were instructed to treat the revenue as given to them by Ryan. Why would anyone believe something so fundamentally dishonest that it refuses to be scored by the usual referee?

I find the ideas he proposes incomprehensibly stupid. He wants to take money paid out by Medicare at a fairly efficient rate – estimates of overhead range from 4-12% – and then hand it to insurers whose overhead is estimated to run somewhere between 24 and 33% and may be higher. If we’re talking the current Medicare budget, that would be over $100B paid to an insurance bureaucracy instead of to doctors and hospitals. That might then balloon costs because these people need to be paid.

And how exactly is an insurance bureaucracy funded by tax dollars “private industry”? It’s more like the Soviet Union: a fake private business funded by the government. We’d be taking more of our GDP and converting it into paper pushing instead of productive enterprise. How is that good?

I have a 78 year old mother with early stages of dementia. How is she supposed to respond to an insurer denying claims? How is she supposed to shop for insurance? This means huge amounts of time and effort required from every family just to deal with the vast Ryan bureaucracy. How is that good? Sick and often physically and mentally frail old people would be forced to shop for insurance and then deal with the myriad of issues we all experience in our dealings with that bureaucracy. It took me days to resolve a problem with my daughter’s asthma treatments caused by some person at the insurer not coding it properly. How is an old person going to deal with that? Is this the source of cost savings: making it so difficult for the sick and elderly that they lose their assets and then their lives?

From Bloomberg:

“Confidence among U.S. consumers plunged in August to the lowest level since May 1980, adding to concern that weak employment gains and volatility in the stock market will prompt households to retrench.”

Hmmm. Now what was going on in May 1980? That wasn’t a few months into the second oil shock, was it?

Cutting medicaid and shifting it to insurance companies is a scary proposition.

Insurance companies are probably the worst available mechanism for funding healthcare. Anything that increases their importance in the healthcare system is probably counterproductive to good healthcare for the general population.

What we need is an adequate public health system free to all, along side the private system, like we have for education. Those who wish to pay extra at the private vendors can do so.

As for stimulus, I think we have already gone beyond the optimal level, and are well into the range of diminishing returns for monetary and fiscal stimulus.

Its terrible when economists use their liberal bias (as demonstrated by making arguments based on facts and observed reality) in support of their desired socialist commie policies; we all KNOW that government spending doesn’t stimulate the economy and only makes it worse since all CEOs base their decisions not on actual and anticipated demand, but what the debt to GDP ratio will be in the year 2033 and whether or not they can write off their corporate jet depreciation at a faster pace than a few years ago. We don’t need facts to “know” this stuff; we don’t need facts to know that the financial crisis was actually caused by the possiblity that Obama could be elected following the 2008 elections, and we don’t need facts to know that Obama is the cause of the European debt crisis, high unemployment and incompentent credit rating agencies.

Mike,

Your type of demagoguery is only convincing to those who don’t pay any attention to reality/data. Its funny how you think pure speculation and slogans pass for valid analysis/debate.

Ironically, public sentiment when asked about rolling back government does support it, but then when you ask about cutting any specific major programs (medicaid/social security etc.) they are wholly against it. Also don’t forget about the riots/protests produced in no small part due to such cuts.

To say the US will suffer no adverse effects from fiscal cuts is simply false, it already is experiencing anemic growth too low to lower our very high and persistent unemployment. Austerity in the US has been occurring at the state and local level for over a year now, and even federally as the small spending stimulus died out (don’t forget a large portion of it was tax cuts). These hits to state employment have immediate consequences for those laid off, and the hits to income prevent debt de-leveraging.

To say that government performs no real functions is a very bogus talking point. Teachers educate real students, firemen and police address real fires and real crimes, public workers maintain real roads, and public health services treat real ailments. That claim couldn’t be more absurd.

The funny thing is that while many claim fiscal cuts are designed to benefit future generations, they often times harm the younger generations most. Cuts to education, nutrition programs, and health will harm our youngest citizens most, and the focus on deficits over jobs is preventing young adults from obtaining employment which will permanently damage their resumes.

The point I think many miss, when saying things such as “government just reallocates resources inefficiently, and picks winners and losers”. First I would say in many ways there are plenty of investments/public goods that yield worthwhile returns based on everything we know about growth, infrastructure, education, R&D etc. Second I would say it is “us” in a democracy who ultimately and indirectly makes the decision of what is worth investing in. Thus it is not a failure to aggregate knowledge/wants as is the case with the central planning of communism say.It is very hard to say this is not the ideal time to make such investments, which we will need at some point anyways, with unemployment so high and interest rates so low. Beyond that, what is important is that this income gets spent and re-spent, giving signals to the private sector about what production needs to be focused upon as the economy begins to recover, and this process lowers the debt overhang.

You can say spending did nothing, but it spurred growth for the limited time it lasted before waning away, and if you look at the data from 1929-1937 it becomes pretty clear that as deficit spending increased, employment was immediately and greatly benefited, and this process actually increased private investment, it did not crowd it out. Meanwhile the austerity/rapid budget balancing of 1937 crashed the economy and private investment, because the private sector had yet to alleviate its debt overhang sufficiently.

Menzie: My comment was not directed towards earlier discussions on the application of Ilzetzki to the U.S.’s case. Since you didn’t seem to understand my comments, I will assume that I was not clear enough earlier. So let me clarify.

My comments were only directed to this post. As far as I can tell, you are making two main inferences here, (i) the U.K. fiscal contractions were a bad idea and (ii) this is a lesson for the U.S. to learn.

My original comment was simply that looking at GDP or employment changes is woefully incomplete. You responded with a link to a Roubini article in which they estimate the fiscal multiplier of–as applied to the U.K. experience. I followed up with the question of how can you reconcile the Roubini number with significantly different numbers in Ilzetzki. That was the extent of my comment. I made no reference on the applicability of Ilzetzki’s numbers to the U.S. experience.

However, if you would at this time like to address the apparent logical inconsistencies with argument (ii) and your characterization of the U.S.’s economy I would be very interested in that as well.

Jeff I’m not following your point. Britain is, by Ilzetski’s definition, a “closed” economy. So is the US Britain also has its own currency with the ability to make it as floating or as fixed as the government desires. So does the US.

Also, the Ilzetski study is vulnerable to the same criticism as many other VAR studies of the fiscal multiplier; viz., that there are precious few actual data points that are relevant. We have many data points for recessions, but very few for recessions in which the Fed is confronting a liquidity trap. And since the Bank of England has been at a 0.5% short term interest rate for the last 30 months, I’d say that qualifies as a liquidity trap. Again, just like the US.

Mike The point, dear Menzie, is that monetary policy and fiscal policy are impotent in our current situation.

No, the point is that conventinal monetary policy is impotent, which is why we need the only remaining policy tool left in the Bat Utility Belt (apologies to those under 45).

The purpose of austerity is not to invigorate the economy, but to keep us from flushing resources down the toilet for our children. It’s to reduce the debt burden NOW while we have the highest bargaining power against all the moneyed interests whose rent seeking built this mountain of debt.

This is an all-too-common view. And it’s also wrong. It’s based on some confused ersatz economics notion of macroeconomic policy being just like household finance decisions. So the thinking is that mom & dad have this pile of wealth, and the more they spend on themselves the less is available for their heirs. Well, this is just wrongheaded. You are confusing stock variables and flow variables. The economy is operating well below potential GDP. In fact, Krugman has a nice graph showing potential GDP to actual GDP. Basically you could think of it the recession as a kind of level shift. The trendline today is running roughly parallel with potential GDP, but there is a large gap. The size of the gap represents lost output. And it accumulates each year. What GOP policies are doing is handing future generations a GDP path that is permanently below the long run trend line. Your kids and grandkids will not thank us for what we’re doing today. If you want to help them, then close the output gap.

Your view also betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of how costs are passed along from one generation to another. If we use fiscal stimulus today the actual economic resources are consumed today, not in the future. Again, GDP is not like physical money that you can stuff in your mattress for a rainy day. Use it or lose it. The only econonic cost that is passed to future generations is the discount rate, which is pretty low right now. Yes, if we borrow $1T today then we have to pay back $1T tomorrow; but we also have $1T in additional output. The loss to future generations is the interest cost.

Government produces no income or wealth – it robs the private sector of income and wealth, hauling it away in a leaky bucket.

More ersatz economics. Whether you know it or not (and I suspect you don’t), what you’re claiming here is a special version of the labor theory of value. Karl Marx was the last economist who believed in the labor theory of value. I guess that makes you a Marxist without your even knowing it.

Jonathan I have a 78 year old mother with early stages of dementia. Towards the end of his life the university hospital diagnosed my dad as suffering from dementia. He was a physicist and mathematician and could solve math problems right up until the end; but the executive function part of the brain was completely shot. He could ratiocinate, but was unable to make rational judgments. Curiously, towards the end of his life he suddenly turned very conservative and actually voted Republican for the only time in his life. I gave him a Krugman book towards the end. He liked it and agreed with it; but then voted for Dubya. Go figure. So I get your point. There is no chance that the elderly are going to be able to figure out complicated medical plans.

Rich Berger, proclaiming his love of the Ryan budget: you won’t hear a lot of that from the GOP in the coming election.

Slug: By either measure, Ilzetski defines the U.K. as open and the issue is not one of data availability.

Menzie, I just filled my car gas tank with water to get to the store. It got me to the end of the block. Now I have to walk the remaining way.

If the question is did a reduction in G reduce growth, then yes of course. If the question is did a reduction in G increase long-term growth, then the answer is also most likely yes, depending on the cuts being made.

Jeff According the Ilzetski paper that I’m familiar with he defines an open economy as one in which the sum of imports and exports is more than 60% of GDP. By that definition Britain is not an open economy. It’s roughly 40% for Britain.

And again, the paper that I’m familiar with is based on a VAR analysis. And the issue is precisely the number of data points.

Jeff: OK, perhaps I was unclear. My point is in the latest version of the Ilzetzki et al. paper presented at the NBER IFM, UK was categorized under de facto and de jure measures as open — so if there was a place one would expect a expansionary fiscal contraction to occur, it would be there (although once it hit zero policy rates, then one might not). And yet the fiscal contraction illustrated in the Roubini.com article I linked to in my previous comment to you has not resulted in a big expansion. The US, by contrast, was categorized as closed using the de facto measure, so we should have even less expectation of a expansionsary fiscal contraction. In addition, the US was classified as “large”, in which case once again, multipliers are expected to be larger.

So to be explicit: (i) I don’t make a judgement that cutting spending and increasing taxes are bad for the UK, but that given the state of the UK economy, and the conditions it operates under, expansionary fiscal contraction is unlikely; the Ilzetzki et al. results are consistent with that view. It may be that fiscal consolidation is necessary, so maybe this is the best policy. But don’t expect an ebullient expanding economy. (ii) The relevance for the US is that the US is large and closed; hence the case for expansionary fiscal contraction in the US is even less strong.

I hope that chain of logic is sufficiently clear.

Thank you, yes that does make your position clearer. Unfortunately your logic is still flawed. Let me illustrate. You claim that we have not seen an expansion in the U.K. as a result of their fiscal consolidation measures. I still say the evidence is incomplete, but let’s take it as fact for now. Now we look at Ilzetzki and we see that according to their measures they are open, highly indebted and have a floating exchange rate. According to each of these measures, Ilzetzki’s results predict that we should see small multipliers associated with the U.K.’s policy choice. To the extent that growth as not been strong enough in the U.K., this is inconsistent with their results.

Now what can we do at this point? We have a couple of options. One, we can say that this result is so far from what we expected that it’s worth tossing out the whole model. In such a situation, we are back to square one. It tells us nothing about what to expect in the U.S.

On the other hand, we can choose to input this new observation into the model and get slightly less robust results. This seems to me to be the more prudent approach. But what does this tell us about the U.S.? Well, you also argue that the U.S. is large, close, quasi-fixed, and just over the debt threshold. In such a case it belongs in the set of observations with large multipliers. However, it also means that it does not belong in the same subset as the U.K. Thus again, the new U.K. data tells us nothing about what to expect in the U.S. Thus to state that the case for fiscal contraction in the U.S. is less strong does not follow.

And we’re still waiting for expansionary fiscal expansion in the U.S.

One would think after 3 years of failed 10% GDP deficits, the Keynesians would have a new idea.

Menzie My point is in the latest version of the Ilzetzki et al. paper presented at the NBER IFM, UK was categorized under de facto and de jure measures as open — so if there was a place one would expect a expansionary fiscal contraction to occur

In their paper they claim that Britain is classified as an open economy, but by their own definition I don’t see how that works. They define an open economy as one with a ratio of (exports + imports)/GDP > 60%. In their chart the UK barely squeaks in. But according to this month’s trade bulletin imports for 2010 were 477.9B pounds and exports were 428.6B pounds. GDP was 2.29T.

http://www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdir/trd0811.pdf

So by my reckoning (428.6 + 477.9) / 2290 = 39.6%.

That seems like a bit more than a rounding error. In fact, it looks suspiciously like 100% – 39.6%, which is approximately equal to the 60.1% they claimed in their paper.

W. C. Varones We’re also still waiting to see the implementation of fiscally expansive policies. The original stimulus bill only had about $710B in actual stimulus (note: $77B was a continuation of the AMT adjustment). And of that $710B, about 40% was in poorly structured tax cuts, with the other 60% mostly spread out over 3 years. And the stimulus was not backloaded enough to sustain whatever impulse was achieved in mid-2009. Finally, the net fiscal stimulus, after adjusting for state and local cuts, has turned out to be pretty much of a wash. So sometime in the future, after the GOP has been long buried and forgotten, maybe we’ll have a real opportunity to test whether fiscal expansion works. We do know that compromises in which one economically illiterate political party is happy at getting 98% of what it wants is not a recipe for success.

2slugbaits: I have the same export and import figures (from the national accounts). However, for nominal GDP, I have 1453.616. So (428.6+477.9)/1453.6 = 0.624. (I think the 2.29 trn figure is in USD terms, but I’m just guessing.)

Jeff: Well, to paraphrase Zhou EnLai, the evidence is still incomplete on the French Revolution. You are right that literally taken, Ilzetzki et al. found open, highly indebted countries on floating would not evidence large multipliers. However, when the UK started its stimulus, debt-to-GDP was not particularly high. And by the time stimulus was underway, UK policy rates were effectively at zero. If you read the paper, or had been at the presentation, or had asked the authors, the interpretation of why fixed rate economies responded more was because interest rates were essentially fixed in such instances. So, we should have expected fairly large positive multipliers in this more nuanced, rather than literal, interpretation of the paper’s findings. And that’s what we find, rather than the negative multipliers implied in the expansionary fiscal contraction literature. But I’ll say this — we will eventually know more when we get more data.

I agree the Ilzetzki et al. results don’t bear directly on the UK and US comparison in this context. What does is that the various studies that have found an expansionary fiscal contraction effect have typically been open economies. The UK fits into that category; the US does not. If the effect doesn’t show up in the UK, should we expect it to show up in the US? Given the results in the three papers from the NBER IFM and ME panels, which I linked to, I don’t think so.

Menzie Yes, you’re right. That would make sense.

Still, the paper seems to sweep under the rug some important differences in the contexts of some recessions. It’s easy to see how a country could successfully manage an expansionary fiscal contraction if the central bank has room to lower rates and if the rest of the world is in a recovery. The big success stories for expansionary fiscal contraction are Canada and Sweden, but those conditions were unique and could have been predicted with a standard Mundell-Fleming model. If you’re Canada, a beggar-thy-neighbor policy of recovery works if your neighbor is a large country with a booming Clinton economy to pull you along. None of that applies today. I appreciate the fact that the authors were attempting to introduce some kind of conditional factors in the literature on fiscal multipliers, but it seems to me that they missed the one really big condition…and that’s the state of the rest of the world. The panel VAR data does not include any timeframe when virtually all developed countries were in the same slump.

One can make lots of arguments about tweaking some variable in economics (e.g. fiscal stimulus) at different times in history as long as one can confidently assert “all else equal”. But it is important to ask is all else equal? I say no, and at least one reason that Steve Kopits and Jeffrey Brown clearly understand (and James Hamilton too): The supply of oil. We are in a context more like 1980 except even worse because the potential for future production increases seems bleak.

Fiscal stimulus can work if other factors aren’t constraining growth. But clearly other factors (and oil is not the only big one) are constraining growth.

Another constraint: The economy’s total debt to GDP is quite high. Ken Rogoff and Scott Sumner are arguing (at least as I understand it) for inflating away some of that debt because they see it as an impediment to growth. So is fiscal stimulus really the right tool when debt is the problem and fiscal stimulus involves increasing the amount of debt?

If debt and oil are the two biggest impediments for growth then at least Rogoff and Sumner have a plan for one of them. But what about oil? I do not see a solution for that one for many years.

I really appreciate Slug bringing up the success of Canada, but Slug has his timeline wrong. He talks of “a standard Mundell-Fleming model. If you’re Canada, a beggar-thy-neighbor policy of recovery works if your neighbor is a large country with a booming Clinton economy to pull you along.” During the time of the 1990s supply side boom Canada was attempting to grow its economy with a typical leftist Keynesian-monetarist model. The result was high unemployment and a declining currency.

Contras that to the Canada of today with low taxes (a corporate tax rate of 25%), reduced governmnet regulations, and a currency under control. From an unemployment rate of 8.7% in 2009 Canada’s unemployment in has fallen consistently and is now at 7.2%. The value of the Canadian dollar has also increased from above 1.50 to the $US so that now it is a parity, primarily from the rapid decline of the $US but also because the Canadian dollar is becoming stronger.

Menzie has clearly shown the results of the UK high tax/severe austerity program but what of other countries?

The government of Spain if you will remember threw its weight behind “green” jobs. The result has been a disaster with the economy continuing to decline.

Italy attempted to borrow its way to prosperity and is on the verge of collapse.

The ineffectiveness of bailout is grossly evident in Greece.

Then there is the grand Keynesian-monetarist experiment in Japan that has resulted in two decades of a stagnant economy.

The real world is pointing the way to recovery, but the hubris and arrogance of US politicians and monetary authorities refuses to learn from the experience of others.

Canada is just more proof that the supply side formula still works.

Then consider Sweden as it reduced governmental interferrence in the economy and

Ricardo,/b>, thank you for the expanding number of positive examples.

2slugs, I see, even again, you have moved to a prior position of mine, (the Obama stimulus plan was poorly constructed.) You still have not gotten off that “too small” horse, but the other move shows some maturation in thinking. Congratulation!

A general question: the conservatives are noticing a huge dissonance in the liberal community. Their core beliefs have now been implemented and measured. Most open minded folks would admit those beliefs and their implementing policies are failed, or at best less than successful. The list of examples is too long to address here.

The end product of the realization for liberals is to turn on Obama, the implementer of their less than perfect beliefs/policies. They have taken the easy path instead of admitting their beliefs/policies are failed.

Sorry,liberals. We’ve tried your ideas and they are failures. Time for change.

Ricardo The result was high unemployment and a declining currency.

Ummm, no. A decision to push down and then hold down the currency is a rational response to growing unemployment. Sorry, but I don’t understand this almost Freudian connection that many conservatives have between a weak currency and some anthropormorphic projection of national sexual prowess.

Canada entered its recession with central bank interest rates north of 8% and that central bank cut rates aggressively. In other words, no liquidity trap. And because of the booming US economy Canada was able to enjoy a boom in exports (over 40% increase in 5 years). And despite the depreciated currency Canada was able to increase imports by almost as much. Low interest rates fueled investment. If you’re an Austrian who wasn’t able to peek at the future data you would have talked about malinvestment.

And one of the reasons Canada was able to weather the international financial recession is that Canadian banks were heavily regulated. Canada has a single-payer healthcare system and a heavily regulated financial sector. If that’s supply side economics, then sign me up.

I agree CoRev, it is time to change. But the menu is not very appealing right now.

Most of the positions we read on the blogs stem from very old arguments — many of which have been coopted by one special interest group or another — it is really not worth repeating them.

If you do take the time to read Keynes, you will find that he was a problem-solver. Problems like: why is unemployment so high when interest rates are so low? That kind of thing.

So, CoRev, why does the private sector not respond to low interest rates? One possible answer is that the private sector already has a great deal of debt. So to take on more is a big risk. And in any case, where is the demand growth that would justify that risk?

Now that the 2009 stimulus package has been spent, we will see a proof that lower levels of government services will provide a boost to the economy — as the states wind down their unemployment insurance programs and other stabilizers.

On the other hand, some of the commentators are just ideologues. They will never abandon their quasi-religious positions. They will claim that some external factor spoiled the interpretation. Or they will claim that the opposition (GOP, Dems) prevented a full implementation of the program.

And still the data comes in: unemployment remains high. Banks are still insolvent. Entire states in the US/countries in the EU are insolvent.

What if the data proves you wrong? Will you change your mind?

CoRev You have a failing memory. At the time the so-called “stimulus” was being legislated I said that it was too small by half. I said that there would be a bump up in GDP in 2009 and that GDP would fall off in 2010. Remember, that was the “backloading” discussion? You argued that backloading was just a political trick to juice the economy in 2012. I said that if that was the intent, then it would surely fail. My point was that the stimulus needed to be both larger on the front end and much heavier on the back end in order to sustain things. It’s a simple math exercise. If the stimulus increases GDP in one year and the economy has not yet kicked-in on its own, then you need more stimulus the next year. Don’t you remember any of this, or is it all a complete blank? I never said the Obama plan was well constructed. Where did you get this? How do you get to the conclusion that liberal beliefs have failed when the economic recovery has evolved almost exactly as some of us predicted and feared. And where is all that inflation that you kept warning us about? Where are the high interest rates that you and Eric Cantor were predicting? Where is all the crowding out? You have to do more than just predict that Obama’s approach would fall flat; you also have to get the other predictions right, and there you completely failed. We can both agree that Obama’s stimulus package was poorly constructed, but it matters why we believe that. And as we now know, even Obama’s top advisors were warning him that it was inadequate to the task. Obama’s main mistake was in assuming that he would get a second bite at the stimulus apple if the first one wasn’t big enough. He didn’t appreciate just how deeply evil Mitch McConnell really is.

One of the problems with conservatives, and particularly conservatives without any formal training in economics, is that they don’t actually understand Keynesian arguments. They think they do, but they don’t. That’s why you continue to misrepresent (or misremember) actual arguments. I suspect that this also explains why you apparently believe I thought the Obama plan was well constructed even though I specifically criticized it for being weak tea with too much emphasis on tax cuts. In your world you don’t actually understand the other side’s argument; you only know your side and assume that the other side must be the exact opposite. Krugman made this same point the other day, and he’s got it exactly right. Tell us, have you ever actually read Keynes? When people talk about the Hicks-Keynes model, even for pedagogical purposes, do you have any idea what they are talking about? I’m guessing not. So why do you think you are qualified to criticize arguments that you can’t even accurately represent?

Don’cha just love 2slugs’ and other liberal argument techniques? This is what I said: “2slugs, I see, even again, you have moved to a prior position of mine, (the Obama stimulus plan was poorly constructed.) You still have not gotten off that “too small” horse, but the other move shows some maturation in thinking. Congratulation!

A general question: the conservatives are noticing a huge dissonance in the liberal community. Their core beliefs have now been implemented and measured. Most open minded folks would admit those beliefs and their implementing policies are failed, or at best less than successful. The list of examples is too long to address here.

The end product of the realization for liberals is to turn on Obama, the implementer of their less than perfect beliefs/policies. They have taken the easy path instead of admitting their beliefs/policies are failed.

Sorry,liberals. We’ve tried your ideas and they are failures. Time for change.”

Now go back and reread 2slugs’ counter, especially his Keynesian arguments.

Yes, I do remember the older arguments differently than 2slugs, because much of it focused upon the ability of infrastructure spending to provide short term stimulation. Which, BTW, even Obama had to admit, but which we still see calls for from liberals.

Grandiosity,

I think the answer is simple and obvious when take a deep breath and relax before thinking.

The cost of existing debt must come down in line with current growth prospect.

CoRev Yesterday there was a big piece at cnn.com about the huge problem with water infrastructure in this country. Water mains are breaking everywhere, but cities and states do nothing except emergency patches. Even where I live we have boil orders all the time following a water main break. There are plenty of infrastructure needs. And the concern that it wouldn’t have been effective because only “shovel ready” projects had to be considered was a stupid Republican demand, not a liberal demand. Some of us knew the history of financial recessions and any talk about infrastructure spending kicking in after the recovery was well underway was just ignorant talk. And you obviously don’t remember the discussion very well because what had you upset was what you considered excessive backloading of the stimulus. It’s bad enough that you can’t remember my argument correctly, but you can’t even correctly remember your own argument.

BTW, I see you chose not to answer my question about your having read Keynes or understanding the Hicks-Keynes model. Want to try again? And you don’t want to talk about your predicitions of high inflation, high interest rates and crowding out.

2slugs, why should I answer a question re: my economic education? Sure, ‘m familiar with the ISLM, but admit that’s the gist of my knowledge. I am not a practicing economist, and haven’t studied nor used it in decades.

This is what I said: “…because much of it focused upon the ability of infrastructure spending to provide short term stimulation.” Now, after two yeaqrs of actual experience with the 2slugs/Obama stimulus, who was more correct re: short term stimulation?

2qlugs, you are a fascinating study in narcissism. Like Obama’s faults it seems impossible to admit when you are wrong. You have been arrogantly wrong quite a bit these past months.

I don’t remember corevs arguments, but my problem with the stimulus was that it boosted consumption rather than investment. Investment being things that reduce costs, thereby freeing up money to repair balance sheets and increase discretionary income long term so that people can express their demand.

Ricardo: Of course oil and natural resource exporter Canada did great in the last decade. That’s to be expected for reasons that mostly lie outside of Canadian domestic economic policy. Rising Asian demand for natural resources and resulting high prices were great news for Canada even as they were bad news for the United States.

Stefan Karlsson puts the argument perfectly in this post:

Why Different Outcome To Austerity?

In the debate over the effects of fiscal austerity on growth, all sides can point to examples that seems to help their case.

Those who argue that deficit reduction can help growth can point to the Baltic states who pushed through even tougher measures than for example Greece and Portugal, and who are now booming, with Estonia seeing GDP increase 8.4% compared to a year earlier, Lithuania 6.1% and Latvia 5.3%.

On the other hand we can see that growth in for example Britain and Portugal has slowed considerably, and in Greece we have seen a 6.9% contraction the latest year (that came after a 4% contraction in the year to Q2 2010).