Senator Shelby, Ranking Republican of the Banking Committee, has sponsored The Financial Regulatory Responsibility Act, which seeks to restrict implementation of Dodd-Frank, and require benefit-cost analysis for financial regulation. To quote Sen. Shelby: “American job creators are under siege from the Dodd-Frank Act.” [1] Now, it’s clear that British authorities have primary responsibility for regulating Libor (after all, the “L” in Libor stands for “London”). But I think it’s useful to consider this question because clearly similar concerns will arise in markets in the US sometime in the future.

Let’s move on, then. On Monday, July 16, in the wake of the Libor scandal, Senator Shelby responded to a question about Libor:

BARTIROMO: SENATOR, LET’S FACE IT. YOU ARE THE RANKING REPUBLICAN ON THIS SENATE BANKING COMMITTEE. I MEAN, ARE YOU MISSING ALL OF THIS? DAY IN AND DAY OUT? WHY MORE SCANDALS? EVERY TIME WE TURN AROUND HOW WILL WE GET CONFIDENCE BACK IF PEOPLE DON’T TRUST THE POLICEMAN AT THE — YOU KNOW, IN CHARGE.

SHELBY: WELL, THE POLICEMAN HAS TO BE DILIGENT. IF YOU REFER TO THE REGULATORS AS POLICEMEN WHICH THEY ARE, OF THE BANKING SYSTEM, FINANCIAL THING, THEY HAVE GOT TO BE INVOLVED. THEY CAN’T JUST HAVE SOME INFORMATION SOMETHING IS GOING WRONG AND QUIT AND KICK IT DOWN THE ROAD AND HOPE IT NEVER COMES UP AGAIN. THAT’S BASICALLY WHAT HAPPENED AS FAR AS WE KNOW IT THIS TIME. THEY HAVE GOT TO BE DILIGENT. THEY’VE GOT TO SAY GOSH WE HAVE TO INTEGRITY ABOVE EVERYRTHING IN OUR BANKING SYSTEM. WE USED TO HAVE IT. WE NEED TO GET THERE AGAIN.

An observation: If the regulators are constantly criticized for implementing regulations (see Senator Shelby’s comments on CFPB [2]), they are unlikely to vigorously pursue violations. However, the question at hand is whether the proposed legislation would have allowed intervention/regulation. To answer that, we need assess the costs of the Libor manipulation. Morgan Stanley has provided some back of the envelope calculations. From FT Alphaville (h/t Naked Capitalism/Yves Smith):

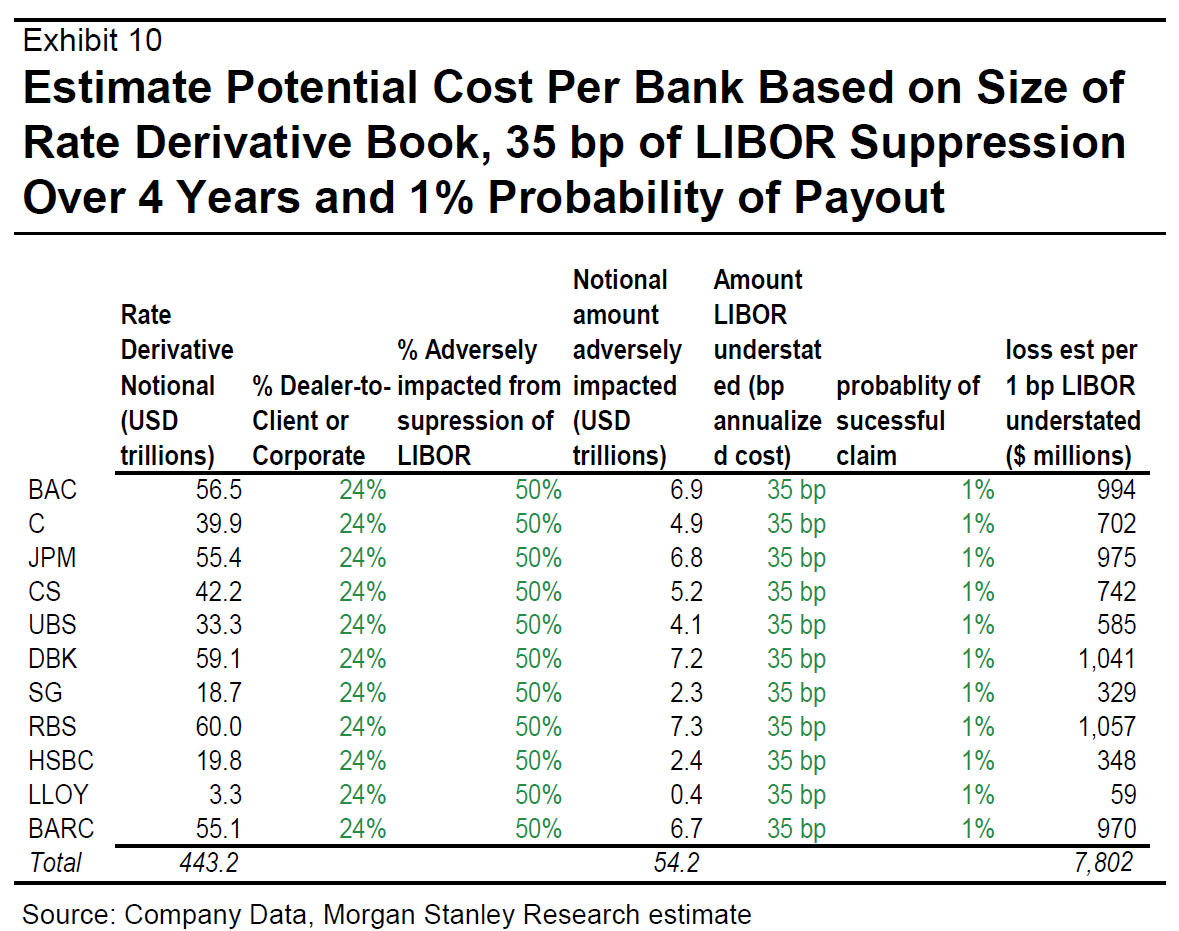

Exhibit 10 from Morgan Stanley via FT Alphaville.

So, as Yves Smith summarizes:

$350 trillion net notional x 25% customer trades x 33% net loss incidence from manipulation x 1 basis point revenue capture

That gives you $2.9 billion across all 16 banks, or $180 million per bank. Times four years, you have $720 million. Compensation as a percent of investment bank revenues is typically 40% to 50%. So we have, on pretty conservative assumptions, roughly $290 to $360 million in extra comp on average per bank for Libor manipulation. This would presumably have gone to comparatively few people (recall Bob Diamond trying to say only 14 traders were involved, although the FSA said “at least 14″). Assume 20 per desk. plus everyone in the reporting line above would have benefitted, as well as the C level execs. So how many people is that? Maybe 50 tops? OK, let’s be really charitable and assume only 50% directly benefitted those people, the rest helped improve bank-wide comp (all those back office types, etc). Even assuming that, you have an average of $2.9 to $3.6 million in extra bonuses per person over the four year period.

The point here is pretty simple. Even if you go to some lengths to cut the numbers way down, you come to the conclusion that if this manipulation had any meaningful impact on the profits of the swaps and derivatives desks, a comparatively small number of people who’d be very cognizant of the manipulation by virtue of seeing the contrast between posted Libor versus actual market prices, likely profited very handsomely. And the people up the line would have benefitted as well.

So we have a guess, after the fact, about the costs. And yet I am confident that regulation of Libor will be resisted, even as outrage is voiced about manipulation, because that will cut into rents.

Since the violations occurred in London, it might not be the same groups that call for regulation but I’m guessing the same arguments will arise, as were levied in 2010. As Jeffry Frieden and I wrote in Lost Decades (p. 165) about the modest attempts to regulate finance, such as in Dodd-Frank:

Not everyone agreed with the regulatory changes adopted in

2010. Some felt they went too far in imposing restrictions on the

private sector. One group of conservative leaders argued against the

Dodd-Frank legislation on the grounds that it “would increase the

size and scope of the federal government, regulating every phase of

economic activity.” For them the proposal was another misguided

attempt to overregulate businesses. “Due to the bill’s excessive taxes

and government red tape,” they argued, “families and small business

owners would no longer have access to low cost credit, and

a bureaucrat would stand between them and living the American

dream.”38 Conservative activist Grover Norquist charged that the

reform put in place “costly and colossal new regulations . . . burdens

banks with billions of dollars in new fees and restrictions . . . creates

a massive new government agency with the power to monitor virtually

any American citizen’s or business’s bank accounts.”39

In other words, as long as finance captures legislators and regulators, “light touch regulation” (which I gather approximates Senator Shelby’s view of optimal regulation) will be favored, and excess returns will flow to the financial sector, because the costs are easy to see, but the benefits hard to discern, ex ante.

One final point: It might have been the case that during the height of the financial crisis, there was an incentive for regulators to look away, as lower Libor kept interest rates low elsewhere in the system. [3] (In fact, it was pretty well known that Libor was not representative of borrowing costs at the peak of the TED spread.) But for the rest of the time, it is unclear to me that allowing a financial price to be distorted enhances the efficiency of the system. In other words, I believe that government intervention is sometimes necessary in the midst of a full-blown crisis. But the under-quoting of offer rates for the entire past five years clearly does not fall under that category.

Sen. Shelby might come around to supporting Dodd-Frank if they retroactively renamed it Shelby-Dodd-Frank. Sen. Shelby never saw a project or bill he didn’t like if it has his name on it. I travel to Alabama often enough to see Sen. Shelby’s smiling face at just about every ribbon cutting ceremony for some highway, airport improvement or public building with is name on it. But he makes good anti-government speeches for the Tea Party crowd, so they eat it up and keep voting for him.

My understanding is that the Bank of England (BoE) did a little more than just look the other way. The BoE tacitly encouraged banks to misstate the Libor because the BoE didn’t want the public to know just how many banks were on the edge. So the lie bought some breathing space. Makes one wonder about our own US Treasury’s “stress tests” during the crisis.

It may be that we’d be making an interesting bet of our own. Europe is making regulation more of a reality, though I want to see London require more reporting of capital flows. If we resist, then what happens? Do we benefit or do we get hurt? Do we attract short-term business and take on that massive long-term and even long-tail risk which regulation tries to prevent? We would be committing ourselves to more of the casino. Maybe the real question is this: who is the house? In a casino, the house wins. If we the people are the house, then we win. But it seems far, far, far more likely – given the Libor example, given the financial crisis, given so much more – that we’re not the house. That means we lose because we become players by default and not merely through “too big to fail” notions. So my guess is we’d be making the classic suckers’ bet.

Menzie

Your spin on this makes me think we are living in the Twilight Zone.

The largest regulator in the world, THE FED, knew what was going on. How would MORE regulation have helped? If the FED looks the other way, what regulatory body is going to take action?

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444330904577536671111719732.html?mod=googlenews_wsj

Excerpt:

Mr. Geithner and the rest of the Federal Reserve were so unalarmed about the claims of inaccurate Libor rates that they even continued to use Libor as a benchmark. In September 2008, the New York Fed extended an $85 billion line of credit to rescue AIG. The interest rate for that loan was based on the three-month Libor rate, plus 8.5%. Two months later, the Fed restructured the rescue package, lowering the interest rate to Libor plus 3%….

And so mild was its concern that when the Fed set up the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility, or TALF, in November 2008, it set the interest rate for the emergency program on the one-month Libor rate, plus a premium. That program, which eventually lent $1 trillion to banks and hedge funds, was administered by none other than the gumshoes at the New York Fed.

All of this happened after the New York Fed had briefed the Treasury and regulators in Washington about reports it had received—often from the banks themselves—that banks were fudging their Libor submissions. No wonder, as the Bank of England’s number No. 2 Paul Tucker recently put it, “alarm bells” didn’t go off…

On the evidence currently available, Mr. Geithner and his fellow regulators were inclined at the time of the crisis in 2008 to treat understated Libor rates as a minor issue

Reality, hello…is anybody there?

No one is compelled to use LIBOR. There are many other standards available. If I were Gorton, I would argue that it is used because it i) reflects the borrowing costs of a range of banks that are ii) presumed to be solvent and liquid. It is intended to be an “information insensitive” rate. During the financial crisis, it became sensitized to information, because it spoke to market perceptions of liquidity and solvency, rather than normal borrowing costs. But LIBOR borrowers used the rate under the assumption that it was information insensitive. A LIBOR borrower does not want his rate tied to the creditworthiness of the reporting banks. He does not care what the banks’ cost of capital is. He is looking for a decent reference to set the non-crisis interest rate.

Therefore, during a time of financial upset, it was entirely appropriate that the rate should be normalized, as the rate itself is a public good. The banks acted–if I follow Gorton’s reasoning–exactly as they should have. In essence, this is nothing more than the suspension of market to market, in this case, on the income statement rather than the balance sheet.

The proper policy response, I believe, would have been for the BoE and/or the Fed to declare a type of force majeur and have the banks issue a “normalized” LIBOR as being in the best interests of the financial system as well as LIBOR-based borrowers. To my mind, this is unquestionably the appropriate policy response. The fault of the banks is that they implemented the right policy without the sanction of the relevant central banks. It is time for the central banks to recognize the issue and create a structure which permits the survival of the LIBOR standard during periods of systemic financial crisis.

No one is compelled to use LIBOR. There are many other standards available. If I were Gorton, I would argue that it is used because it i) reflects the borrowing costs of a range of banks that are ii) presumed to be solvent and liquid. It is intended to be an “information insensitive” rate. During the financial crisis, it became sensitized to information, because it spoke to market perceptions of liquidity and solvency, rather than normal borrowing costs. But LIBOR borrowers used the rate under the assumption that it was information insensitive. A LIBOR borrower does not want his rate tied to the creditworthiness of the reporting banks. He does not care what the banks’ cost of capital is. He is looking for a decent reference to set the non-crisis interest rate.

Therefore, during a time of financial upset, it was entirely appropriate that the rate should be normalized, as the rate itself is a public good. The banks acted–if I follow Gorton’s reasoning–exactly as they should have. In essence, this is nothing more than the suspension of market to market, in this case, on the income statement rather than the balance sheet.

The proper policy response, I believe, would have been for the BoE and/or the Fed to declare a type of force majeur and have the banks issue a “normalized” LIBOR as being in the best interests of the financial system as well as LIBOR-based borrowers. To my mind, this is unquestionably the appropriate policy response. The fault of the banks is that they implemented the right policy without the sanction of the relevant central banks. It is time for the central banks to recognize the issue and create a structure which permits the survival of the LIBOR standard during periods of systemic financial crisis.

“…it is unclear to me that allowing a financial price to be distorted enhances the efficiency of the system.”

Unless it’s a politically appointed bureaucracy like the Fed doing it.

tj: Last time I looked, London was not in the US. Last time I read, 15 of the 18 participating banks were non-US. Last time I researched things, the reason why AIG FP located in London was because it was …offshore. Hmmm. Maybe not Twilight Zone; maybe not even Night Gallery.

Bryce: Fed funds has an adjective “Fed” for a reason. Libor is supposed to be a private rate, set between banks.

Perhaps! The hot ticket for folks over 75 is foreclosure on an underwater “home equity” loan, according to an AARP report today on NPR. They are using the $ to live.

Ask a price in a dealing room and one may hear a quote, ask again for a more accurate price and one may hear a quote sustained by “ last price seen and paid”, the same should have applied to the LIBOR as quoted within its fraternity club.

When reading through analysis and comments, costs be they social or private, regulations, fiduciaries duties, efficient markets hypothesis are the outrage and put at the forefront . A decade long of collusion between the financial operators and the governments administrations, the central banks and ancillaries functions and all of the sudden “all the women of small virtues are willing to become chairs makers of beadles” and the LIBOR the catalyst.

Since the worries are for now and only the social costs of markets prices manipulations, it may be worth to include all the markets that is, long term interest rates, commodities, real estates.

Mervyn King: Jackson Hole Conference – remarks to the Central Bank Governors’ Panel

“I see Alan as the central banking equivalent of the non-playing captain of a Davis Cup team, encouraging the younger and less talented members, and stressing the importance of footwork, timing and getting into position early.

Alan, thank you for raising the respect which others give to our discipline of economics and our profession of central banking. “

Thanks Menzie, that’s interesting. I am surprised that you read nakedcapitalism.com, did not thought you enjoy Smith.

Well, I wonder if you will ever turn to zerohedge.com (does not mean that I recommend this to you). Anyway, thanks again for your effort.

To sum it up Menzie : The banks made fraudulent loans on inflated homes to unqualified borrowers to bundle them under a phoney AAA rating and sell them to investors who attempted to limit their risk exposure with derivatives based on LIBOR which the banks were manipulating.

Well Menzie, sounds like banking lobbyists are earning their money keeping regulators off the industries backs. Any ideas ?

I think this is badly estimated.

As a disclaimer, I work in a hedge fund (and used to trade LIBOR swaps). I was effectively on the other side of the banks.

Pre-2008 spreads in the LIBOR panels were tiny (often less then a 1bp), so manipulation couldn’t really move the market that much. I think we are talking between 1/8 and 1/4 of a bp. Bid-offer spread on swaps are between 1/2 and 1/4 of a bp, so you are talking similar order of magnitude to the explicit bid/offer. Unwinding the trade before expiry generated similar transaction fees and you would routinely add that cost when evaluating trades.

Also the credit component of LIBOR is a bug not a feature. The original economic reason to enter into trades was to have an index that captured the borrowing cost of a risk-less bank. There were no risk-less banks in 2008 anymore. The explosion of the spread was an unexpected (and in main ways undesired) event. It’s not what you wanted when you entered in the trade. Before 2008 the market thought the panel mechanism would be enough to shelter you from the credit component, but it was wrong.

Also a large percentage of swaps notionals are between the banks in the panel and they couldn’t really benefit from that. To extract a lot of money from this, they would need to compare their individual reset risk (the exposure to the fixing on each day) and build some kind of system to divide the spoils (as they would have different positions/desire to manipulate on each day). It would be pretty complicated and it would leave a lot of evidence…

The behaviour was still unacceptable and it should and will be punished, but you shouldn’t exaggerate things anyway.

Visa was fined 7bn for running a cartel on merchant fees. That’s a much bigger deal and yet it got a tenth of the comments…

Menzie

Oh I see, the FED has no influence overseas. The FED could not have said, “Clean up LIBOR or no swaps. Clean up LIBOR or no help from the U.S.”

Regulation is a wonderful thing. It’s the regulators who are the problem.

tj: I didn’t say it had no influence. But not sure Fed could’ve swept in with black helicopters to clean it all up, if the banks involved weren’t US. Now, you could argue the Fed should have been more aggressive in communicating information to BoE. I think that is Simon Johnson‘s view. And if you are saying regulators should be more insulated from capture by financial interests, I’m all with you. But for sure, hamstringing regulatory authorities and denying funding is not the way to instill aggressive action.

So Menzie, thievery & distortion of interest rates are fine as long as the govt[Fed] is doing it?

Just as a manipulated LIBOR takes from one side of the credit/debt equation, so do the manipulations of the politicians who run the Fed. The Fed systematically screws savers–especially the salt of the earth type people, the little people that govt pretends to look out for. They do this for the benefit of the banksters & that colossal borrower, the Federal govt itself.

Again the irony of the modern liberal loving a system that benefits the politically-connected at the expense of the common man.

Bryce: I guess it depends what you mean by manipulate. Libor is an average of “indicative” offer prices, and should represent the rate at which institutions will lend. Fed funds is the average of actual “transactions” prices. Do you understand the difference?

To be honest, I haven’t followed this story all that closely, but my understanding is that the banks per se weren’t the ones manipulating the LIBOR rate for the banks’ benefit, but rather it was individual traders who were calling in favors for their own benefit because they were overleveraged in one position or another. Sometimes they wanted the LIBOR lowered and sometimes they wanted it raised. The fakery went in both directions. And sometimes the direction of the faked LIBOR estimate actually hurt some other side of the bank.

The real lesson here is that when banks and financial institutions oppose regulations like Dodd-Frank and tell us that they can regulate themselves, the LIBOR scandal tells us that in fact they can’t even regulate their own internal employee compensation policies nevermind their external relationships. If the internal compensation packages in the financial sector are so perverse that banks can’t even control their own employees, then what hope is there that they can self-regulate their external relationships.

Bryce You seem really hung-up on this fanciful notion of some true north star of value from which all other prices can be honestly and fairly determined. I have no idea where you picked up this stuff, but no one has believed that in almost 150 years.

Menzie: Are we speaking a different language? “Fed funds is the average of actual “transactions” prices.” Excuse my not being a professional economist, but that has no meaning to me. Interest rates–these days even longterm rates–are what the Fed is willing to create enough money to make them. What am I missing?

Slug: Free market prices are essential to efficient allocation of resources. That people understood that better & more broadly 150 yrs ago…even 80 years ago doesn’t make it untrue today. To get free market prices, you need free market provision of banking & money. Not the corporatist [as Mussolini called economic fascism] system we have.

Steven Kopits is exactly correct. This whole LIBOR non-scandal is simply a ploy by the Laviathan to accumulate more power.