Fated to a big trend slowdown?

Israel Malkin and Mark M. Spiegel at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco have just published an interesting Economic Letter:

Many analysts have predicted that a Chinese economic slowdown is inevitable because the country is approaching the per capita income at which growth in other countries began to decelerate. However, China may escape such a slowdown because of its uneven development. An analysis based on episodes of rapid expansion in four other Asian countries suggests that growth in China’s more developed provinces may slow to 5.5% by the close of the decade. But growth in the country’s less-developed provinces is expected to run at a robust 7.5% pace.

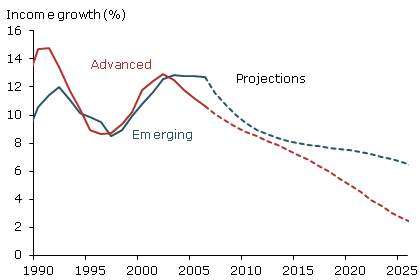

This article highlights that, regardless of the depth of the cyclical downturn, the long term trend is of great concern. The authors provide this graph to illustrate how their ECM of growth in four East Asian economies [1] can be applied to regions in China to show how prospects might diverge.

Figure 3 from Malkin and Spiegel.

This article is part of a longer debate that has been running – namely whether there is a middle-income trap. On one side is Eichengreen, Park and Shin (2011), who argue for a $17,000 threshold (constant international dollars), (and parenthetically argue that the slowdown is more likely for countries that maintain undervalued exchange rates).

One critique argues that one wants to see at what ratio to the leader’s income per capita a country’s growth slows down; implicitly, this cuts out of the sample countries that remain mired in a low income trap. Andrew Batson at Gavekal notes that deceleration in growth (where the criterion for deceleration is not cited) can occur at quite wide-ranging ratios: 20% for Thailand, 50% for South Korea and 80% for Finland. This is shown in Figure 4 from Batson (2011).

Figure 4 from Andrew Batson, “Is China heading for the middle-income trap?” China Economic Insights (GaveKal Dragonomics, September 6, 2011). [Not online]. Dotted lines pertain to ratios at which growth slowed.

Which one is a more appropriate approach? In my mind, it depends on what the question is. If one wants a characterization of income per capita for all countries, the Eichengreen et al. methodology is more appropriate. If one wishes to condition on the prospect of convergence (keeping in mind convergence is quite rare), then one might want to use the latter approach.

For more on China, see here.

Menzie, are there allowances for cultural differences? For example, Finland is largely homogenous with less tolerance for lavish wealth. While Finns want to succeed, they want to fit within Finnish culture.

But China? China has historically rewarded those who excel, whether in scholarship or bureaucracy or business, and there is next to no cultural restriction on achievement of wealth or on displaying it publicly.

Menzie, allow me to point to an entry last year on my blog http://shiftingwealth.blogspot.fr/2011/11/ways-round-middle-income-trap.html?m=0 which shows that escape from the trap has not been rare.

I agree with Helmut.

A brief look at WEO data suggests that per capita income at constant prices in Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Korea has been growing at 3-4% per annum on average since 1995 or so.

I don’t see anything much too worry about there.

I think of it this way:

• In Phase I of China’s growth story, China exported goods from her developing coastal provinces to the advanced consumers in the West.

• In Phase II of China’s growth story, China will have to export goods from her developing inland provinces, to the advanced consumers of her own East Coast.

• So the East Coast Cities are like her own internal “Western Civilization” now. So vast she is.

Hi Menzie, Thanks for your interesting blog post on our letter. My only comment is that Israel Malkin and I based our error correction model on the experiences of four successful Asian nations (Hong Kong, Japan, Korea and Taiwan) and found that the middle-income slowdown appeared to kick in at an even lower level than the larger Eichengreen, et al sample (around $10,000). Mark

One thing that gets lost in the whole “when will China surpass US” debate is that China’s demographic outlook is so poor that there is a good possibility that the USA will have more people than China by the end of the century. Even if China can get to better than 50% of US GDP per capita, there may be only a couple of years where Chinese GDP>US GDP.

I think Steven is spot on. It’s important not to view China as just one homogenous whole – there’s actually a lot of variation between regions and where they are up to in the development process.

Initially we have seen impressive growth along the East coast provinces and have both the central and north-eastern provinces to come in Phase II.

It’s worth noting that growth in Phase II will also come from opportunities for further productivity gains in the developed coastal provinces as they shift to a more service-oriented approach.

However, the really big bogey on China’s horizon is it’s rapidly ageing population in combination with Chinese peoples’ reliance on real estate as the investment instrument of choice…