Today, we have a guest contribution from Marios Zachariadis, Associate Professor of Economics at University of Cyprus.

The Cypriot economy is being shocked via numerous channels. First, the loss of working capital by Cypriot businesses: 40%-90% of their deposits over 100,000 euro held at the two main banks. The second is a liquidity shock due to the remaining deposits in these banks being frozen for months. Overall, 90%-100% of deposits above 100,000 have either been confiscated or frozen in the two banks. The third channel relates to a significant loss of confidence in the banking system. The last two shock channels are amplified by unprecedented internal and external capital controls forced upon Cyprus. The fourth channel relates to the loss of a good part of a major sector i.e. banking, finance and related services. The fifth relates to the adverse wealth effect on a number of households and professionals who saw most of their wealth in the form of savings disappear overnight. One last adverse shock has also been in place for a while as Cyprus implemented austerity measures several months ago, much before the actual agreement for a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Troika. Moreover, the current rescue plan’s obvious non-sustainability makes it rational for households and firms to expect more austerity, which affects current consumption and investment plans.

Summary

- A number of distinct channels via which shocks hit local economy.

- Forecasts upon which the sustainability analysis has been based optimistic. Debt sustainability report here.

- Burden for Cyprus not sustainable. Financing needs here.

- In part because of unfair deal:

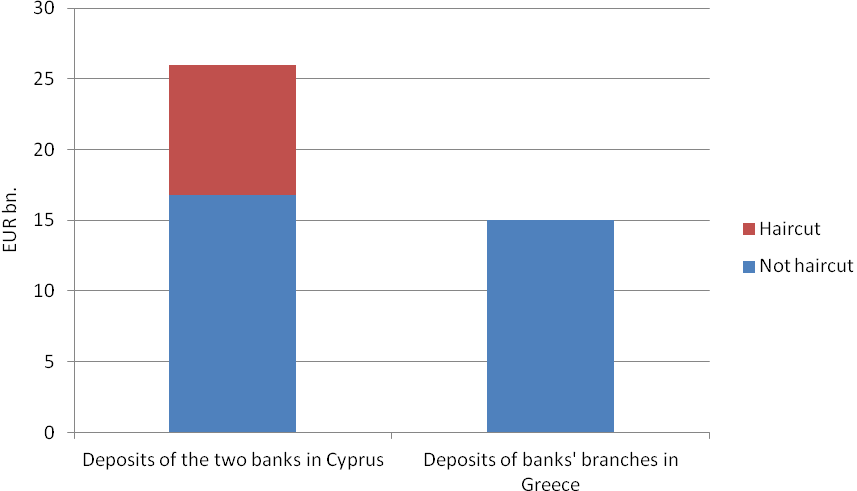

- No haircut for depositors of Cypriot banks’ branches in Greece to avoid contagion there.

- Emergency Liquidity Assistance used by one bank in Greece forced on another bank in Cyprus.

- Cyprus forced to sell all bank branches in Greece at fire sale to avoid contagion to Greece.

- Troika against Cyprus using Private Sector Involvement (PSI) for foreign investors.

- Remedy by:

- transfer of 2-3 billion euro via Marshall-type plan,

- retroactive Banking Union or

- debt restructuring e.g. Official Sector Involvement.

The overall likely outcome is a double-digit dip in GDP growth for 2013 with positive growth rates out of reach for several years thereafter. This might explain why the IMF refrained from publishing forecasts for Cyprus in its most recent World Economic Outlook as these would either contradict optimistic Troika forecasts in Cyprus MoU or look bad down the road.

What can be done to remedy the situation? It goes without saying that Cyprus needs to implement measures agreed in the MoU in a timely manner, and do more to implement growth-enhancing reforms by fixing structural problems that pre-existed before the arrival of these shocks. But this will not suffice. The burden undertaken by Cypriots is unsustainable. It has become so large due to the indecisiveness of the previous government but also because of the intrinsic unfairness of the solution imposed on Cyprus.

Why is the magnitude of this burden unfair and as a result unsustainable? To begin with, one simply needs to ask the question: Why were the deposits at the branches of the two Cypriot banks in Greece excluded from haircuts? These amounted to about 15 billion euro of deposits as compared to 26 billion in the same two banks in Cyprus (Dixon 2013), which suggests that about a third of the haircut, i.e. up to three billion euro, could have come from depositors of these banks in Greece. One might understand why the banking system in Greece and the Eurozone should be protected in this manner. After all, the will of the ECB and the Commission to avoid any direct contagion risk was evident in their insistence that Cyprus sold its bank branches in Greece, or the Troika would not agree to a bailout. But Cypriot depositors and taxpayers cannot afford to offer insurance that costs them a couple or more billion at such heavy discount.

One can also understand that the Central Bank of Cyprus and the Eurosystem could not go ahead and realize a loss by selling inadequate collateral of a bad Cypriot bank (LAIKI) that the ECB appears to have funded via Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) for a long time after it was apparently insolvent, without impairing ECB’s ability to keep doing the same for other Eurozone banks. Xiouros (2013) argues that ELA has claims only against the collateral so what was done to avoid a loss could be illegal. On the other hand, realizing such a loss would amount to illegal monetary financing and would have exposed the ECB, undermining its ability to help troubled banks just a few months before the German elections. Thus, the need to push the envelope by adding the ELA of a bank that has been shut down (LAIKI) to the balance sheet of another private bank (BoC). The ELA that was used for liquidity of LAIKI depositors in Greece should not permanently burden another private bank. It would even be preferable to have this loss placed on the government’s shoulders.

In that case, it would become obvious that Cyprus needs debt restructuring, either Private (PSI) or Official Sector Involvement (OSI), which the European Commission is also trying to avoid for political reasons e.g. PSI for Greece supposedly a unique event (Gulati and Buchheit, 2013) and OSI a forbidden word before German elections. It should, however, become clear to Europe that if there is no PSI so as to insure the euro zone from contagion, there will have to be OSI later.

In the absence of some sort of Marshall-type plan in the form of targeted EU transfers of 2-3 billion euro and some form of retroactive application of the Banking Union or PSI/OSI for Cyprus, we are looking at a Great Depression disaster. Cyprus’ hope is that, if anything, by resolving the moral hazard issue this bail-in precedent makes Banking Union more likely. In that case, Cyprus needs and deserves some sort of retroactive implementation of the Banking Union for part of its ELA burden. These numbers should be understood in the context of a country with a GDP of less than 18 billion euro that, driven by its bankers and politicians short-sightedness, has already contributed to Greece’s rescue program a quarter of its GDP (4.5 billion) due to the European political decision for a PSI for Greece in 2011.

References

- Dixon Hugo, April 2013, Bad Resolutions, Reuters Breaking Views, [link]

- Gulati, Mitu and Lee C. Buchheit , March 20 2013, Walking back from Cyprus, VOX EU article, [link]

- IMF World Economic outlook April 2013, [link]

- Xiouros Costas April 2013, Handling Emergency Liquidity Assistance of Laiki Bank in Cyprus rescue package, [link]

This post written by Marios Zachariadis.

Marios Zachariadis wrote:

…the current rescue plan’s obvious non-sustainability makes it rational for households and firms to expect more austerity, which affects current consumption and investment plans.

What is still not understood is that “austerity” is not a government policy but a consequence of government mistakes. While we can debate “austerity” as a policy it will not matter. Austerity will come and if it is not sufficient to wash out the malinvestment from the system it will continue to come.

Zachariadis is exactly correct. There will be more austerity to come in Cypress and this will be true whether their is an EEU bailout of not. All the bailout does is involved the EEU in the mistakes. The austerity hammer that is falling will fall. The only decision that can be made is how many will feel the impact. Current decisions by the EEU appear to be positioning the whole EEU under the mallet.

The Marshall Plan was to sustain nations until they could overcome the destruction of war and produce again. What is being proposed here is not a Marshal Plan but a Hooverite plan – not a plan to raise nations from the disaster of war, but pouring productive resources down a black hole.

Depart, devalue, default.

Yours hopes and vanity make you want to be “European”, in the sense of belonging to the Euro zone. Financial realities, and frankly, the way Eurozone has treated you, dictate that you are not.

I fear an attempt to remain in the Euro zone will lead to unprecedented and unnecessary suffering for the island’s residents, and may well fail anyway.

Better to write off the past and start anew.

CR reports that vehicle miles traveled (VMT) fell by 1.4% in Feb. 2013 compared to Feb 2012.

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2013/04/dot-vehicle-miles-driven-decreased-14.html

Feb 2012 was a leap year, and so had one more day than Feb. this year, which would seem to negate the headline conclusion. If we look at rolling 12 month VMT, the year ending Feb. 2013 was virtually unchanged from the year ending Feb. 2012. VMT is not improving, but not getting worse, either.

Implied efficiency gains, however, are miserable. Gasoline consumption fell by 0.7% in Q1 ’13 compared to a year earlier. According to the EIA STEO, VMT rose by 0.3% to March (Q1). (Where do they get their data, if DOT just released Feb. data?)

Thus, if we allow changes in VMT and gasoline consumption as proxies for efficiency improvements in the use of oil, then transportation efficiency is improving at a lowly 1% per annum. Given that we anticipate oil consumption to fall on average by 1.5%, and given that we’ve now had six years of high oil prices which should have prompted material improvements in vehicle mpg, this is not a cheerful statistic.

If we allow oil consumption (and not just gasoline) versus VMT as a measure of efficiency, the situation is even worse. US oil consumption actually increased 0.5% in Q1 ’13 compared to a year earlier. If we allow VMT increased by 0.3%, then transportation efficiency actually deteriorated 0.2% in the last year, a result even grimmer than the gasoline-based statistic above.

Much has been written about driving habits (http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2013/04/why-are-younger-americans-driving-less.html), but the plain vanilla explanation remains the most plausible: high oil prices continue to force Americans from their cars, adversely affecting economic activity and hiring on the margin.

Greeks (and I am one) are experts at blaming others for their problems, just take at look at how Greece has acted for the last decade. It seems that many Cypriots, who have the same hellenistic heritage, share this trait. Here’s a long post blaming the Cypriot crisis on everyone but Cyprus.

For instance, the author asks why the depositor haircut wasn’t applied to branches in Greece as he subtly tries to shift the blame to his “cousins” across the Aegean. But the problem is that the Cypriot branches are insolvent, not the Greek branches, so why should there be a transfer from those Greek branches back to Cyprus? Is he advocating that the deposits of all subsidiaries be seized? I wonder how that would go over with the British regulators of the Cypriot subsidiaries located in the UK? It’s absurd that the author would suggest that the deposits in the foreign subsidiaries be transferred back to Cyprus — just imagine the protests that would arise if that was attempted.

The author goes on at length about how the ELA to Laiki Bank being transferred to Bank of Cyprus (an odd request given that the Bank of Cyprus took on all of Laiki’s other liabilities). The author notes that the ECB kept the ELA in place for many months after it became apparent that Laiki was insolvent (in part to allow Cyprus to have its own election while not in throes of a crisis). Bur rather than acknowledging the great service the ECB afforded Cyprus, the author implies that the ECB was in error and should suffer a loss. That’s gratitude for you.

The authors solutions to the crisis all involve other people’s money being given to Cyprus. Cypriot policies got their country into the crisis and until Cyprus acknowledges their own responsibility in the problems, it is difficult to be sympathetic to their plight.

Apparent oil demand in China rose only 1.9% in March compared to the same month last year (Platts, http://blogs.platts.com/2013/04/23/china-apr13/). This is a very weak performance, and if I extrapolate from oil to GDP, it suggests that China GDP growth is now sub 5%.

This would explain recent weakness in Brent prices, today around $100. This is below our expectations (although not inconsistent with GS, BP or Citi forecasts). Given that oil consumption has been supported in the last two months by inventory draws, this weakness is hard to understand. On the other hand, a rapid cooling of the Chinese economy could explain recent softness in oil prices.

Hey Kopits,

Maybe you should get your own blog instead of derailing all the comment threads with posts about oil.

I know your blood is 50% brent, but seriously, it is distracting and confusing.

To kosta: In fact most of the bad loans of Laiki bank were in its branches in Greece. Similarly, most of the ELA of about 9 billion had been used for liquidity of depositors in Greece. Overall, the Greek branches (unlike the UK ones) were as insolvent or more insolvent. So they were not spared from the haircut because they were solvent.

In my opinion, Steven Kopits is one of the best oil analysts in the world, especially in regard to the demand side.

And I suppose that those who believe in infinite oil supplies, the Tooth Fairy and the Easter Bunny don’t like to be reminded of the “Finite Earth Theory.”

In any case, regarding China and oil prices, a couple of points.

First, China’s domestic oil production has been flat of late, so even if we are seeing a decline in their rate of increase in consumption, we may not see much of a decline in their rate of increase in net oil imports. Note that the rate of increase in US net oil imports was 11%/year from 1949 to 1970, but it increased to 14%/year from 1970 to 1977, after US crude oil production peaked in 1970. And incidentally, China’s rate of increase in net imports from 2005 to 2011 was below our 1949 to 1970 rate of increase.

Second, I believe that we saw April to June declines in monthly Brent prices in 2010, 2011 and 2012.

In regard to problems in developed countries, in the context of the post-2005 decline in Global Net Exports of oil (GNE), as developing countries, led by China, consumed an increasing share of a declining post-2005 volume of GNE, here is something that I first wrote three years ago:

The OECD “Thelma & Louise” Race to the Edge of the Cliff

Steven Kopits: “Depart, devalue, default.”

And it appears that some Irish agree too.

Dan White: The economic return of Iceland has proved that the joke was on us (Ireland)

http://www.independent.ie/business/irish/dan-white-the-economic-return-of-iceland-has-proved-that-the-joke-was-on-us-28949864.html

Sorry, Nick. Just post ’em when I find ’em.

OK, then for Cyprus.

What do we really want from Cyprus? What’s at stake here? Why do Cypriots need to be part of the Euro zone? Why don’t Norway and Switzerland feel the same need?

Having spent many years in Hungary, I can tell you that the EU and Euro zone can represent civilization, good governance, and ability to feel a peer in Europe. But boil it all down, and it’s really about governance. The Swiss and Norwegians have good governance–so they don’t need the EU or Euro zone. It does not confer status to them.

What Cyprus needs, what Greece needs, is good governance. Kosta rightly points out that the essential problem is that Greeks and Cypriots (and I could add most Latin peoples) tend to externalize their problems. This is the dependent behavior in a paternalistic system: “Daddy should fix it,” or “It’s America’s fault.”

Fixing this requires the modification of the relationship between the governed and decision-makers, and we effect this change by installing new incentives. That is, we pay politicians for performance. Anyone you pay for performance has a name: employee. An employee is not your Daddy. It’s your servant. It’s someone you pay because they did what you wanted. They are subordinate to you.

Fixing incentives in Greece or Cyprus is easy and straight-forward. It is the prize which Merkel and the finance ministers seek to achieve by punishing Russian depositors. But they have done nothing to change incentives, only punished those who transgressed some imaginary boundary.

If the EU could buy good governance in Cyprus for $10 bn, wouldn’t that be a good deal compared to the social horrors unfolding there?

Kosta’s problem can be fixed. The sense of responsibility can be internalized, if incentives are aligned.

Marios,

I have trouble understanding why Cyprus doesn’t default. Is it that without the Euro they won’t have the entrance into Europe that gave their banks an edge? I ask because I think the world would quickly forget default, as it has with Argentina and others, and I don’t see this bailout doing much more than impoverishing Cyprus for a long time.

A second question: do Cypriots believe the bailout is as bad or nearly as bad as it will get? I mean my suspicion is that with Cyprus now committed, what is demanded will rise and rise.

Same question as Jonathan. Why doesn’t Cyprus just default? Haven’t the markets already priced in the near certainty of Cyprus bailing out of the euro? Russian mobsters might not want to visit Cyprus after a default, but why should default cause the Danes or the Dutch to cancel their vacations?

To Jonathan: Yes, even if Cyprus implements all necessary measures as I recommend above, numbers just don’t add up so it will have to default eventually, unless other measures are adopted by the Eurozone as described above. However, Cyprus will face huge non-economic costs in addition to any economic cost. For example, defaulting will worsen even more its relations with its only potential allies in Europe, creating problems in its territorial dispute with Turkey, and in Cyprus ability to use its natural gas reserves, if proven, down the road.

@Marios: The banking system in the EU is set up such that each country is responsible for the banks in its borders. Since the problem is in Cyprus, caused by Cypriot policies, then the solution has to be found in Cyprus. It makes no sense for Cyprus to transfer money from the deposits of foreign subsidiaries back to Cyprus to make Cypriot depositors whole. The reverse is also true. If Marfin bank (the Laiki subsidiary in Greece) failed, Cyprus would not be responsible for making its depositors whole, Greece would have that responsibility.

Now, you could argue that the EU should have a banking union where all the banks are backstopped by the same organization. I agree, however, such a banking union would not have saved Cyprus. For such a banking union to be implemented, there would be strict regulations on the size of banks, the assets they held and the types of liabilities they took on. The Cypriot banks got to be too large and held far too much high risk Greek debt. Why was this allowed to happen? If there was a banking union, the Cypriot banks would have been constrained in size and the crisis would have been avoided, but constraining the banks would have cost Cyprus none the less.

Rather than complaining about the unfair deal, why not acknowledge that Germany and the EU are lending Cyprus, a bankrupt country, a huge amount of money, and be grateful for the help you’re getting. If you’re going to blame someone, why not blame your own politicians, regulators, and bank executives who allowed your banks to get so large and so overleveraged in the first place.

@Jonathan

I’m going to second Marios’s opinion about the non-economic costs of a default and exit from the Eurozone. Keep in mind that the Euro project is a political project, meant to bind countries together. One of the motivations for Cyprus joining the Eurozone was to firmly entrench itself in Europe. Take a quick look at a map and you’ll note that Cyprus’s nearest neighbors are Turkey, Syria and Lebanon. Leaving the Eurozone would push Cyprus towards their orbit.

It is in Cyprus’s political interest to stay in the Euro.

Kosta. There’s plenty of blame for locals and the article acknowledges that. You can also see more on that here http://homepages.econ.ucy.ac.cy/~mzachari/link1.htm and in particular here http://blog.stockwatch.com.cy/?p=1592

Certainly expanding into Greece was a mistake in retrospect. However, you seem to miss the main point. Most losses (say bad loans) were due to the branches in Greece. Thus, you have still not answered the question: why not haircut those branches. There is an acceptable answer and it’s in the article: stop contagion to Greece and the Eurozone. However, that’s a cost that Cypriots cannot afford to pay alone. A couple of other things need to be cleared: first, you should really look up the difference between branch and subsidiary. Second, if there’s anything that should be clear is that Cypriots and Greeks have very different interests here. If there is a great fault of Cypriots is that they have failed to understand that. As far as Greeks like you are concerned, you should understand that we have the right to speak up for our own interests which in this case do not coincide with yours. Finally, keep in mind that thru the mistakes of its bankers and politicians but also because of the mistakes of the Eurozone plan, Cyprus ended paying for Greece’s bailout and contagion protection more than any other country including Germany as % of GDP. A sum that exceeds 12billion for a country with 18 billion GDP!

@Marios

For the record, I have very little sympathy for Greece and her plight. Cyprus has been managed far better by her politicians than Greece. The nature of Cyrpus’s crisis is far different than that of Greece’s and from what I can tell it stems from 1) a far too large banking sector, 2) a far too lax regulatory system which allowed the banking sector to invest so heavily in Greece, and 3) the inept response to the crisis by the Cypriot leaders (in particular Christofias). Also, I wonder whether the Florakis explosion played a role in contributing to the crisis?

Christofias’s ineptitude is particularly relevant to our discussion. It has been commonly known that the Cypriot banking system was facing huge losses stemming from the Greek writedowns of 2011. The EU/ECB had been pushing Cyprus to intervene and solve this issue, yet Christofias refused to act. The delay of nearly 2 years to ‘lance the boil’ greatly exacerbated the costs of the bailout. You’ve argued that Cyprus should not be responsible for the ELA provided to Laiki, but if Christofias has acted in a responsible manner and dealt with this problem in 2011 or early 2012, the ELA problem would not exist. The ELA was provided to prevent the crisis from occurring until Cyprus could elect a responsible politician who would deal with the crisis. It seems to me that in the end, Cyprus should be responsible for paying back that ELA.

Further on the Greek subsidiaries (branches?), why didn’t Cyprus, or at least Laiki, just abandon those branches? If the Marfin Bank of Greece was such a money sink, why didn’t Laiki just shut down that business, declare it bankrupt, or at least divest itself of those liabilities? If the problem was in Greece, why not just amputate the Greek operations and move on?

I’m not sure I agree with your maths regarding Cyprus’s portion of the Greek bailout. It’s true that Cypriot Banks held a lot of Greek debt, debt that was written down. But I am not sure if those losses should be included in Cypriot’s tally of the Greek bailout. No one forced Cyprus, or I should say Cypriot banks, to load up on Greek debt. If Cypriot banks were reaching for yield and ended up getting burned, well that’s what happens when you reach for yield.

Lastly, if the Greek bailout did hit the Cyprus disproportionately (and I agree, it did), why didn’t Cyprus bring the issue to the attention of the EU/ECB/IMF? Why wasn’t this issue resolved in 2011, instead of letting it fester till 2013?