Today, we’re fortunate to have Alex Nikolsko-Rzhevskyy, Assistant Professor of Economics at Lehigh University, David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan, Professor and Clinical Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Houston, as Guest Contributors.

The issue of rules versus discretion, which has occupied an important role in monetary policy evaluation for over 35 years, has entered the very recent debate over who should be the next Fed chair. Within the last week, John Taylor has written two blog posts evaluating the candidates based on their commitment to rules-based policy, the first favoring Janet Yellen over Larry Summers and the second being even more favorable to Don Kohn. In Taylor’s words, “But the most important question is who is more likely to implement a monetary policy that will help keep us out of a serious financial crisis, and create price and output stability more generally. In other words who will implement a more predictable, less interventionist, more rules-based monetary policy strategy of the kind that worked well when tried, as in the 1980s, 1990s and until recently?”

The leading monetary policy rule is the Taylor rule. In a recent paper, “Monetary Policy Rules Work and Discretion Doesn’t: A Tale of Two Eras,” Taylor identifies the late 1960s and 1970s as a period of discretionary policy, 1980 to 1984 as a transition, 1985 to 2003 as the rules-based era, and 2003 – 2012 (and possibly beyond) as the ad hoc era. He argues that economic performance in the rules-based period was vastly superior to that in the ad hoc period and, while correlation does not prove causation, the timing of events supports the interpretation that (good or bad) policy causes (good or bad) economic performance rather than causation going in the opposite direction.

But do we really know that the Fed followed a more rules-based policy in the 1980s and 1990s than in the 1970s and the 2000s? The problem with this type of analysis is that identification of monetary policy eras is fraught with peril. Whatever the rule, there is always the danger that, since the economic performance outcomes are known, periods with good economic performance will be identified as rules-based while periods of bad economic performance will be characterized as ad hoc.

In a new paper, “(Taylor) Rules versus Discretion in U.S. Monetary Policy,” we propose and implement a statistical methodology for dividing monetary policy into Taylor-rules-based and discretionary eras. We first calculate Taylor rule deviations, the absolute value of the difference between the federal funds rate and the interest rate implied by the original Taylor (1993) rule, 1.0 plus 1.5 times inflation plus 0.5 times the output gap, which assumes that the target inflation rate and the equilibrium real interest rate both equal 2.0 percent. Next, using tests for structural change and Markov switching methods, we identify Taylor rules-based eras where the deviations are small and discretionary eras where the deviations are large. With both methods, neither the number nor the dates of the regimes is specified a priori, and so prior knowledge of economic outcomes cannot affect the results.

When calculating Taylor rule deviations, we want to use real-time data that was available to policymakers when interest rate decisions were made for as long a period as possible. While it would be ideal to use internal Fed (Greenbook) output gaps, these are only available from 1987 to 2007. We therefore use real-time real GDP (or GNP) and GDP (or GNP) deflator data from the Philadelphia Fed starting in 1965:Q4, when the data begins, and ending in 2008:Q4, when the Federal funds rate hit the zero lower bound. We calculate inflation as the annual percentage change in the GDP deflator and the output gap as the deviation from a real-time quadratic trend. We show that the real-time quadratic detrended output gaps provide a closer approximation to “reasonable” real-time output gaps, calculated using Okun’s Law, than alternatives including real-time linear and Hodrick-Prescott detrending.

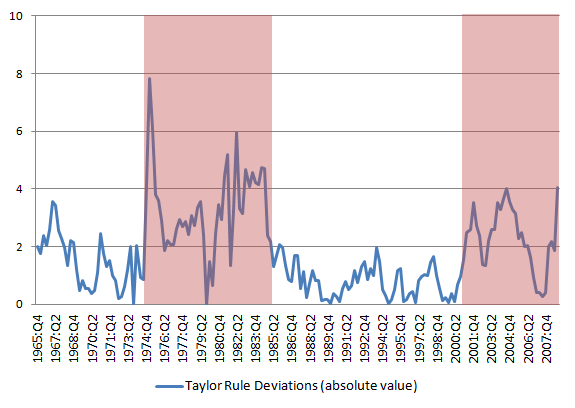

Figure 1 depicts monetary policy eras with tests for multiple structural breaks, allowing for changes in the mean of the Taylor rule deviations. The Taylor rules-based (low deviations) eras are in white and the discretionary (high deviations) eras are shaded. Monetary policy in the U.S. is characterized by a Taylor rules-based era until 1974, a discretionary era from 1974 – 1984, a rules-based era from 1985 – 2000, and a discretionary era from 2001 to 2008. The dates of the breaks are unchanged with tests for multiple restricted structural changes which restrict the mean of the deviations in the two rules-based and two discretionary eras to be the same, and are robust to using Greenbook inflation forecasts instead of realized inflation rates. During the discretionary periods of the 1970s and 2000s, the Federal funds rate is consistently below the rate implied by the Taylor rule while, in the early 1980s, the actual rate is above the implied Taylor rule rate. The size of the deviations in the discretionary eras is more than three times as large as in the rules-based eras.

Figure 1. Structural Change Tests

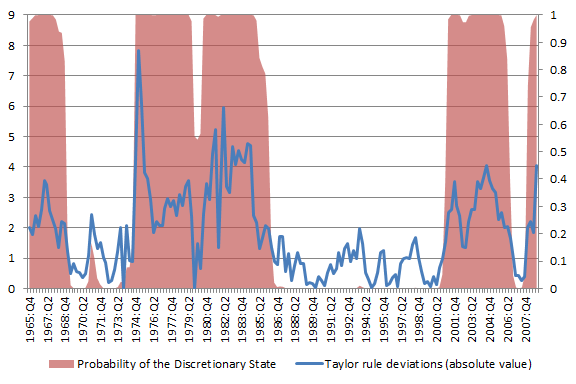

Figure 2 illustrates monetary policy eras using Markov switching methods where the changes in the mean and variance are synchronized. The shaded areas where the probability of the high deviations state is above 50% define the discretionary eras while the white areas where the probability of the high deviations state is below 50% define the Taylor rules-based eras. The four major eras identified by the structural change models are closely replicated by the Markov switching models. In addition, the Markov switching models also identify a rules-based era from 1965 to 1968 and a discretionary era in 2006 and 2007. The results are robust to whether the switches in the mean and variance are allowed to switch independently and if the mean, but not the variance, is allowed to switch between the states. The discretionary and rules-based eras closely correspond to periods where the Taylor rule deviations are above and below two percent. As with the tests for structural change, the size of the deviations is more than three times as large in the discretionary eras than in the rules-based eras.

Figure 2. Markov Switching Model

These results both accord with and reinforce previous work that identifies monetary policy eras less formally, although our dating the start of the most recent extended discretionary era in 2001 is earlier than most accounts. In contrast to previous work, however, our results are not subject to the criticism that the choice of eras was influenced by subsequent outcomes. They therefore provide a better basis to evaluate whether “monetary policy rules work and discretion doesn’t.”

This post by written by Alex Nikolsko-Rzhevskyy, David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan

Well done.

Now let’s be sure not to count that 2001- 2006 as a positive outcome just because contemporaneous conditions felt OK at the time.

That policy incompetence created Greenspan’s bubble and the misery that followed in its bursting.

Rules work when there is no work to be done? Or when the work to be done is simple? The Great Moderation was not a time of stability, inflation fell over the entire period. It had run out of room to fall. Rules work until they don’t.

The largest TBTE banks determine the overnight and discount borrowing rates on the basis of their demand for reserves, or not.

The Fed Chair and FOMC just follows the desires of the TBTE bank owners of the Fed.

Everything else is just clever intellectual sophistry by the Fed Chairperson, Fed governors, and Fed economists to provide political cover for the mischief by the TBTE banks, their total assets now at an equivalent to 100% of GDP and 100% of S&P 500 market capitalization.

If one would internalize this, the Fed would be relegated to its actual minor role of clearing bank reserves and facilitating US Treasury transactions with primary dealers.

Then the scrutiny should be correctly focused where it belongs on who owns the banks, their motivation, what the TBTE banks do, their disproportionate influence, and the effects on the economy, the tax code, wages, wealth and income inequality, the electoral process, and energy and foreign policy.

Again, the Fed exists primarily to run political cover for the TBTE banks’ license to steal labor product, profits, and gov’t receipts with impunity in perpetuity.

“In contrast to previous work, however, our results are not subject to the criticism that the choice of eras was influenced by subsequent outcomes.”

I don’t understand this comment very well. Taylor picked the parameters of his 1993 rule in part because they lined up closely with the 1987-1993 experience. So by default, one would expect this period (and adjacent years) to be qualified as conforming to this rule while other periods are more likely to be identified as following different rules.

I also don’t understand why the authors focus specifically on the structure and parameters of the rule picked by Taylor in 1993. Much work has been done since documenting variants of this rule which account much more closely for Fed’s historical behavior, even during the period used by Taylor to argue for his rule. Why not use these other rules instead for this analysis?

I agree with the previous comment. How can you be sure that a deviation from the Taylor (1993) rule represents discretionary policy? Maybe you simply use the wrong rule.

No question about it. TaylorRules and Seb are dead on. The most common logical error by far is that of a false initial premise. The standard Taylor rule with two variables on the right hand side is the initial core premise of this paper. It is a false one. Its lack of validity as a guide to policy was exposed once and for all during the housing boom. Only an augmented Taylor rule can guide policy. The inclusion of an asset price variable all along would have taken the nominal funds rate up much earlier and higher in the Fed generated boom of the 2000s and saved this country from much calamity. Chairman Bernanke made this identical mistake in logic in his keynote address to the AEA in Atlanta a couple years ago when he torturously defended the Fed’s actions during the boom, his entire logic flowing from this same incorrect initial premise. His paper could not have been more wrong.

Moreover, the US Senate ought not confirm anyone to the position of Fed Chairman who is not on record beforehand (by now) as recognizing this. Neither Yellen nor Summers are. From early-2000, the housing boom built over 25 quarters to its 2006 peak. Once again a housing boom is underway. It is already at the same height the previous boom was 8 quarters into the 25, and accelerating far faster.

By JBH : “The inclusion of an asset price variable all along would have taken the nominal funds rate up much earlier and higher in the Fed generated boom of the 2000s and saved this country from much calamity.” exactly, that’s the point !

Too bad that the FED boss was and is and will be a corporate stooge who does, what he is told (mavbe except Volcker). But Yellen …

I have long held (since about 2005) that the Fed came off the Taylor rule when Bernanke joined the Fed in 2001. He changed it. It was NOT Greenspan by himself. Greenspan wanted to behave this way and Bernanke provided the intellectual justification.

Thanks for the excellent work. Do you think that Yellen’s optimal policy rule can be analyzed the same way?

I’m constantly amazed at how economists can focus on tactical operations (interest rate policy) and ignore the strategic elephant in the room (total credit market debt)… Current policy continues this fiasco with no reduction in the debt/GDP ratio despite our being 6 years downstream of the banking collapse.

Hi guys! Nice post!

To put some of the above comments in a more constructive light, I’ve guessing that you’ve played around with the specification a bit to get a feel for how robust the regime-classification is. If you screw up the specification enough, no doubt the regimes will change….but can you give us a feel for the kinds of things that you’ve looked at that don’t change the classification much?