The U.S. Energy Information Administration last week issued an early release of its Annual Energy Outlook 2014, which shows substantially more optimism about near-term U.S. crude oil production compared to the AEO 2013 assessment completed just eight months ago.

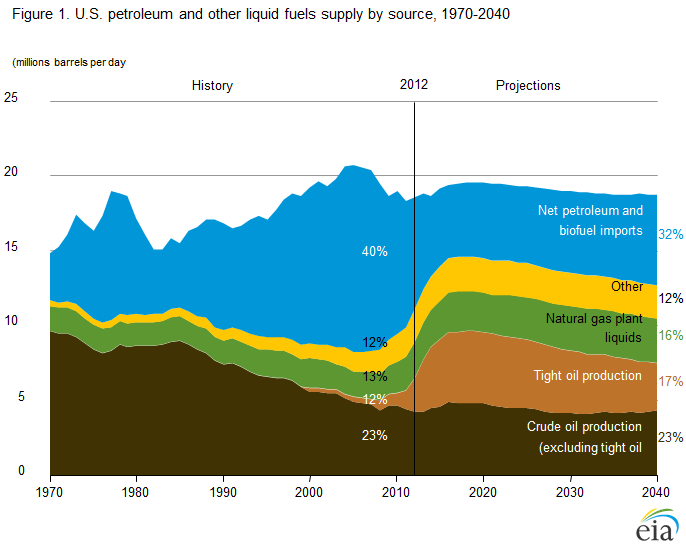

In its April report the EIA was anticipating that U.S. production of crude oil from the tight formations now made accessible with fracking drilling methods would total 2.3 million barrels per day for 2013, and could increase another half-million barrels per day above that before peaking in 2020. But the new assessment is that 2013 tight oil production will amount to 3.5 mb/d– over a million barrels more than the earlier estimate– and will gain another 1.3 mb/d beyond that before peaking in 2021.

| Year | April estimates | Dec estimates |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 0.54 | 0.61 |

| 2009 | 0.63 | 0.69 |

| 2010 | 0.82 | 0.87 |

| 2011 | 1.22 | 1.31 |

| 2012 | 2.00 | 2.25 |

| 2013 | 2.30 | 3.48 |

| 2014 | 2.51 | 4.07 |

| 2015 | 2.63 | 4.49 |

| 2016 | 2.71 | 4.67 |

| 2017 | 2.75 | 4.72 |

| 2018 | 2.76 | 4.76 |

| 2019 | 2.78 | 4.78 |

| 2020 | 2.81 | 4.79 |

| 2021 | 2.80 | 4.80 |

| 2022 | 2.74 | 4.74 |

| 2023 | 2.69 | 4.68 |

| 2024 | 2.67 | 4.61 |

| 2025 | 2.63 | 4.54 |

| 2026 | 2.52 | 4.47 |

| 2027 | 2.44 | 4.42 |

| 2028 | 2.39 | 4.34 |

| 2029 | 2.29 | 4.26 |

| 2030 | 2.19 | 4.17 |

Those numbers along with the EIA’s other projections imply that total U.S. field production of crude oil from all sources would reach 9.6 mb/d in 2019– almost as high as the all-time U.S. peak in 1970– before resuming its decline. If you add in natural gas liquids (which you really shouldn’t) and ethanol produced from corn (which is even less useful [1], [2]), the total would substantially exceed the historical U.S. peak.

|

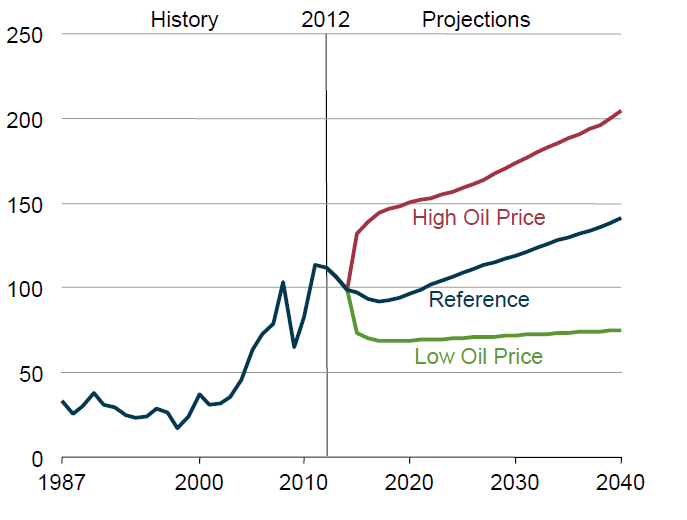

Interestingly, any reductions in crude oil prices associated with this increased production are expected by the EIA to be relatively modest and short lived.

|

Why wouldn’t all this new production have a more dramatic effect on the price of oil? The answer is that, had it not been for the increase in tight oil production in the U.S. and oil sands from Canada, global oil production would actually have declined between 2005 and 2012. And the growth in oil consumption from the emerging economies has eaten up more than all of this new production.

I wonder – on what basis do they justify the future flattening of consumption? Historically, it increases in expansion and decreases in recession, but they seem to have just assumed that it will flatten out.

Thanks. I’d love to see Jeffrey Brown’s take on this projection.

A comment on “product supplied” and U.S. petroleum product exports:

Still gas burned in refineries is consumed in the U.S. and thus counted as product supplied. Net exported products are subtracted and not counted in product supplied. As the fraction of U.S. refinery production which goes to export increases, the proportion of product supplied which provides energy for the production of exports also increases, thus (for certain purposes) skewing product supplied.

We can only imagine how much additional production would have occurred if the Obama administration was as aggressive in pursuing such production as in state and private land.

http://energycommerce.house.gov/sites/republicans.energycommerce.house.gov/files/20130228CRSreport.pdf

With the increase in production that appears to mostly flow to the gulf refineries will there be enough capacity there to also take the inflow from the keystone pipeline from Canada?

Bruce Hall,

The Obama administration has put up more than 100 million acres of continental shelf leases for auction over the last two years and signed hundreds of drilling permits since the Macondo blowout–a total larger than the Bush administrations’. What would you suggest should have been done?

Synapsid, most of the new tight oil is not under the Gulf, is it?

http://www.eia.gov/oil_gas/rpd/northamer_gas.jpg

It is true that production on federal land has increased somewhat, but this has been offset and more by decreases offshore… under the current administration. About 110 million barrel decline in total over two years.

http://www.instituteforenergyresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Oil-production-federal-lands.jpg

Nevertheless, the administration loves to take credit for total U.S. production increases.

http://www.whitehouse.gov/energy/securing-american-energy

So, one must ask whether there is an issue beyond the number of offshore permits… quality of leases, bureaucracy to get production actually started, other? Perhaps the focus should be onshore permits on federal lands.

US oil exports to US consumption and US exports to US proven reserves have tripled since Peak Oil in 2004-05.

US oil exports to US production have quadrupled since Peak Oil.

US proven oil reserves to oil production have plunged 20% since 2011, which is a similar decline (but a much faster rate) as during the mid-1970s to 1985-86.

We’re celebrating the surging level of oil extraction, but we’re burning through reserves at an accelerating differential rate to discoveries and increasing cost in order to export to our imperial military and supranational firms’ subsidiaries’ operations abroad to keep “globalization” going, even though the rate of change of growth of global “trade” and real GDP per capita has stalled.

We’re exporting at an accelerating rate our future domestic energy supplies that we will need to maintain domestic capital formation, investment, production, employment, wages, consumer spending, and gov’t receipts.

The remaining costlier reserves will be less profitable (unprofitable) to extract at a price US households, firms, and gov’ts can afford to burn to maintain real GDP per capita and the current standard of living for the bottom 90-99%. Oil extraction and exports will peak and decline with US and global consumption.

Extracting more costlier domestic oil to export (for war and “globalization”) only means less affordable oil for domestic consumption in the future.

Dutch Disease, Peak Oil, and the Seneca cliff by definition.

If you look where the current hot plays are there is little federal land involved. In Tx the federal government never owned the land, the state kept it when it was annexed since it had been independent for a while before. In ND, most of the land is privatly owned. Only in the Baakken in Mt is there some federal ownership. (Also possibly in the northern extension of the Permian Basin into NM).

Plays only happen in some areas and areas of federal lands are not as prosepective. (The Marcellus in the east also has little federal ownership at least in Pa, Wv, and NY and OH as either the federal government never owned the land or sold it off 200 years ago)

Just for the record, when Texas joined the Union it didn’t have to cede significant lands within what are the current borders because it gave up its claim to sizable parts of what are now Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado and New Mexico. In hindsight, this was a smart thing for Texas to have done; they have avoided the painful relationship the rest of the western states have had with the federal government wrt land ownership and management.

Something that most of our friends in the media seem to be missing is that even with the recent optimistic revisions to their outlook for US crude oil production, the EIA in effect seems to be asserting that US crude oil production (actually crude + condensate) will not materially exceed the 1970 rate of 9.6 mbpd.

It’s one of life’s little ironies that the US, a region that is–so far at least–still a post-peak crude oil producing region, is used to rebut the Peak Oil “Theory.”

It’s as if Daniel Yergin were standing on the top of a building and dropped a rubber ball, and after observing that the ball bounced, and was showing an upward trajectory, observed that the “Theory” of gravity is clearly wrong.

But here is the mathematical problem that almost no one is paying any attention to: Given an ongoing production decline in an oil exporting country, unless they cut their consumption at the same rate as the rate of decline in production, or at a faster rate, the resulting net export decline rate will exceed the production decline rate, and the net export decline rate will accelerate with time. Furthermore, if the rate of increase in consumption exceeds the rate of increase in production, a net oil exporting country can become a net importer, prior to a production peak, e.g., the US and China.

I have continued to be surprised at how much attention is given to the top line production number globally, and not to the bottom line net export number, especially as the developing countries, led by China, have (so far at least) consumed an increasing share of a declining post-2005 Global volume of Net Exports of oil (GNE).

At the 2005 to 2012 rate of decline in the ratio of GNE to the Chindia Region’s Net Imports of oil (CNI), the GNE/CNI ratio would approach 1.0 in only 17 years, which means that China & India would theoretically be consuming 100% of GNE. For more info on “Net Export Math,” you can search for: Export Capacity Index.

While currently increasing US crude oil production is very helpful, it is very likely that we will continue to show the post-1970 “Undulating Decline” pattern that we have seen in US crude oil production, as new sources of oil come on line, and then inevitably peak and decline (2013 annual US crude oil production will probably be about 22% below our 1970 peak rate).

The very slow increase in global crude oil production since 2005, combined with a material post-2005 decline in Global net oil exports, have provided considerable incentives for US oil companies to make money in tight/shale plays. But I think that the assertion by many in the Cornucopian camp that shale plays will result in a virtually infinite rate of increase in global crude oil production is wildly unrealistic.

We are still facing high–and increasing–overall decline rates from existing oil wells in the US. At a 10%/year overall decline rate, which in my opinion is conservative, the US oil industry, in order to just maintain the 2013 crude oil production rate, would have to put online the productive equivalent of the current production from every oil field in the United States of America over the next 10 years–from the Gulf of Mexico to the Eagle Ford, to the Permian Basin, to the Bakken to Alaska.

On the natural gas side, a recent Citi Research report (estimating a 24%/year decline rate in US natural gas production from existing wells), implies that the industry has to replace virtually 100% of current US gas production in about four years, just to maintain the current natural gas production rate. Or, at a 24%/year decline rate, we would need the productive equivalent of the peak production rate of 30 Barnett Shale Plays over the next 10 years, just to maintain current production.

Bloomberg recently posted a column that talked about a “Flood” of North American oil turning into a “Deluge” of oil, because of reforms of Mexican law regarding oil and gas exploration and production (allowing foreign firms to engage in joint ventures).

As soon as I read the recent Bloomberg column, I was reminded of a 2009 Bloomberg column, where they talked about Brazil “Taking market share away from OPEC.” Brazil is a net oil importer, with a recent pattern of increasing net oil imports (even if we count biofuels as oil production).

Note that Western Hemisphere net oil exports from the seven major net oil exporters in the Americas in 2004* fell from 5.9 mbpd in 2004 to 5.0 mbpd in 2012 (total petroleum liquids + other liquids, EIA, million barrels per day).

Regarding Canada + Mexico, their combined net oil exports fell from 2.5 mbpd in 2004 to 2.2 mbpd in 2012.

In any case, Kurt Cobb just wrote an article that analyzes the outlook for a “deluge” of oil from Mexico, which quotes Art Berman and yours truly:

http://www.resilience.org/stories/2013-12-22/if-mexico-is-the-next-brazil-in-oil-production-brace-for-disappointment

*Canada, Mexico, Venezuela, Argentina, Colombia, Ecuador, Trinidad & Tobago

Bruce Hall,

We know where the tight oil is, and have for decades. Most of it is in three plays: Eagle Ford, East Texas; Bakken/Three Forks, North Dakota; Permian Basin, West Texas. There are no permitting problems (the Texas oil patch considers that it has a friend in the White House) and there is very little tight oil on Federal lands. As long as oil prices stay high tight oil will be developed as fast as possible wherever it may be, just as has been the case up till now–in the Bakken development has been so fast that almost a third of associated natural gas is flared instead of holding off on oil development until NG infrastructure is built.

Yep, any administration likes to take credit for oil flow even though most of the development that allows it occurred during previous administrations. Likewise, critics of a given administration like to blame that administration for any problems (even imagined ones like a hold-up in development of tight oil) whether they date to that administration or not.

On consumption trends: The EIA and major oil companies expected consumption in the OECD to recover after the recession. The fact that it subsequently declined has since led them to believe it will continue to decline, but they have no convincing theoretical framework for that assertion. It’s just based on recent experience. This is quite similar to, for example, recent GDP growth forecasts for the OECD. After years of over-forecasting, a number of agencies have very low GDP growth rates into the distant future–as low as 1.4% for the OECD to 2040. But that’s not a result of theory, just as a result of the data coming in since 2010. They’re tweaking coefficients, not the underlying models.

Readers will know that I forecast declining OECD oil consumption back in 2009 (“Peak Oil Economics”, Oil & Gas Investor, Oct. 2009), where I laid out the theoretical basis for such decline.

Now we’re seeing surging US oil consumption. Why this? There can be two explanations. First, China has been effectively out of oil markets since early 2013, thus making oil more available for the advanced economies.

More importantly, I think, US oil production has soared, as Jim indicates above. We know that oil producers get to consume more oil. The question is, how much? I would guess between 1/4 and 3/8th of incremental US oil production should ultimately be consumed domestically, but I don’t have a model for it just now.

Oil to Houston:

The Houston refineries are now swamped with oil, which is increasingly findings its way from Cushing to the Gulf Coast. Gulf Coast refineries are geared to process heavy or sour crude, for example, from Venezuela. Bakken and Eagle Ford crude are light and sweet.

Thus, the industry would like permission to export crude, which is currently prohibited by law. (This should be a post, Jim, as your voice will carry weight in this matter). Here’s Exxon’s take: http://www.foxbusiness.com/industries/2013/12/12/report-exxon-wants-crude-export-limits-lifted/

The industry, however, is not standing still waiting for a green light from Washington. Instead, they are building “splitters” along the Gulf Coast. A splitter takes light crude and splits it into light naptha (a key input for refineries), jet fuel, and propane/butane. All of these can be freely exported.

There are a handful of projects planned or under construction with a crude consumption capacity of 400-500 kbpd. BP is among the participants.

Thus, US regulations are prompting the construction of a number of otherwise unnecessary (light) refineries along the Gulf Coast.

Personally, if I were a Democrat, I would be demanding a lifting of export restrictions on environmental grounds. If I were a Republican, I wouldn’t stand in the way.

As for the price of oil:

The EIA’s reference forecast (above) essentially follows the futures curve down below $90 Brent in 2020.

How exactly do we get there?

On the supply side, the oil majors require $120-130 Brent to break even on a free cash flow basis. Just what exactly is the outlook for these firms in the EIA’s (or I could add, Citi’s) mind?

Will the majors be able to reduce costs? How? The supply chain remains tight as a drum, and the majors are responding by divesting and cutting capex. It’s hard to see how that increases the oil supply.

Or will the majors simply be obliterated by theoretically low cost shale? Is the EIA (or Citi) calling for the wholesale implosion of the oil majors due to low cost competition? That’s a big deal, and if one’s going to make such forecasts, by rights one should have also prepared a eulogy for the IOCs.

Similarly, both WTI and Brent are up on last year, even with surging unconventional production, even as China has been largely absent from demand markets (demand up only 2.6% yoy).

So what happened? Oil prices fell a bit in Q3 and US gasoline consumption soared 4% in a matter of weeks. Where did that come from?

If you use a supply-constrained model, then the advanced economies are starved of oil. If prices ease, this suppressed demand comes back very quickly, and that’s what the data shows. There is a lot of suppressed demand around the globe.

A further corollary of this is that GDP is also suppressed, so a surge in oil consumption will also lead to a surge in GDP. And Q3 GDP was just revised up to 4.1%, and I would guess we’ll see some big numbers in Q4 or Q1 as well.

In any event, I don’t see how oil prices decline into 2020, not unless uncoventionals can consistently increase production by more than 3 mbpd / year. On a net basis, global oil supply growth has been about half that.

Instead, I would anticipate that we are about to see a step up in carrying capacity. I would guess that we’ll soon see the back of the $10x’s and establish a floor above $110 Brent ($112, I would guess). That’s where I think we’re going.

Following are excerpts from a recent OECD study which forecasts (potentially) much higher oil prices:

“A return to world [economic] growth to slightly below pre-crisis rates would be consistent with an increase in the price of Brent crude to far above the early-2012 levels by 2020. This increase would be mostly driven by higher demand from non-OECD economies – in particular China and India. The expected rise in the oil price is unlikely to be smooth. Sudden changes in the supply or demand of oil can have very large effects on the price in the short run.”

“Based on plausible demand and supply assumptions there is a risk that prices could go up to anywhere between $150 and $270 dollars per barrel in real terms by 2020 depending on the responsiveness of oil demand and supply. These projections account for a negative feedback effect of higher oil prices on economic growth.”

Source: http://www.financialsense.com/contributors/joseph-dancy/oecd-study-forecasts-sharply-higher-global-crude-oil-demand

And my 2¢ worth regarding the (so far) pretty steady increase in year over year oil price decline levels:

Recent Global Annual Crude Oil Prices

We have of course seen a cyclical pattern of higher annual highs and higher annual lows in global (Brent) crude oil prices in recent years, but I think that the rates of change between successive annual price lows, or troughs following annual oil price peaks, is very interesting.

Peak to Trough Annual Brent Crude Oil Prices, 1997 to 2013

1997: $19

1998: $13

2000: $29

2001: $24 (1998 to 2001 rate of change: +20%/year)

2008: $97

2009: $62 (2001 to 2009 rate of change: +12%/year)

The 11 year 1998 to 2009 overall of change in trough prices was +14%/year. And then we have 2012 to 2013.

2012: $112

2013: $108 (Est. price)

Based on estimated price for 2013, the four year 2009 to 2013 rate of change in the trough price would be +14%/year ($62 to $108).

The long term 15 year 1998 to 2013 rate of change in trough prices would also be +14%/year ($13 to $108).

If the (+14%/year rate of change) pattern holds, and we were to see a year over year decline in annual Brent crude oil prices in 2017, it would be down to an annual Brent price of about $190 in 2017.

Jeffrey –

Your conclusions are not consistent with a supply-constrained model at carrying capacity.

Once you reach the carrying capacity price, you can only progress from there for the real oil price by increased GDP and efficiency gains. These are unlikely to exceed 5% per annum over the longer term. This puts the real oil price at $156 Brent at year end 2020; or about $178 Brent in nominal terms. (This is not too far from Barclays numbers, by the way.)

The lower end of the OECD forecast is thus plausible, and I would consider it likely. The higher end–$270 Brent–is not. This would require real GDP growth exceeding 10% per annum. On the demand side, that’s not going to happen.

On the other hand, if we allow supply pressures and a budget constraint rising by 5% per annum for consumers, then you could see $270 if the oil supply fell by half. That’s not going to happen barring an end-of-the-universe type of event (which has a non-zero risk).

Further, the higher the oil price in real terms, the greater the pressure for substitution. Historically, the oil-to-gas price ratio on a btu basis might be expected to approach parity in about seven years. That doesn’t seem in the cards now, but it will happen eventually. The higher the oil price, and the greater the differential between gas and oil prices, the greater the impetus to switch to natural gas. This also will tend to cap oil prices from the top. (By the way, this is not reflected in the EIA forecast.)

Again, to emphasize: For a supply-constrained system at the carrying capacity price, the residual (the thing that changes) is not primarily price. It’s GDP. If the price goes up, the incumbent advanced economy consumers cede their consumption and price returns to the carrying capacity price. Thus, the effect is felt in volumes, not prices.

Volumes in turn affect mobility and mobility affects employment and GDP. That’s how the system works.

Steven,

What has happened from 2002 to 2012 regarding the ratio of Global Net Exports of oil (GNE*) to Chindia’s Net Imports, or GNE/CNI, is pretty clear. The ratio fell from about 12 in 2002 to 5 in 2012:

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide1_zps9ff3e76d.jpg

What will happen from 2012 to 2022 is the $64 Trillion question.

What we do know is that that at the 2005 to 2012 rate of decline in the GNE/CNI ratio, China & India alone would be consuming half of Global Net Exports of oil in 2022. What I define as Available Net Exports (or GNE less CNI) are already down by about 15% since 2005 (from 41 mbpd in 2005 to 35 mbpd in 2012).

*Top 33 net oil exporters in 2005, total petroleum liquids + other liquids, EIA

I agree, Jeffrey.

But if we’re looking at prices, then $270 / barrel is not a viable number, at least not in 2020.

Speaking of eulogies:

Shell announced today that it is selling 17% of its assets.

I hardly know how to characterize this development as other than catastrophic.

It also suggests that BP will be up for sale, in months if not weeks.

Steven Kopits: The price of RDSA isn’t reacting to this as if it were big news. Why do you call this catastrophic?

“The price of RDSA isn’t reacting to this as if it were big news. Why do you call this catastrophic?”

Jim, most of the world still uses a demand-constrained oil supply model. In a demand-constrained model, P=MC, thus if P is less than MC, then P will rise. Ergo, you have a transient problem which ordinary supply and demand movements will resolve. This is, in fact, what Shell CEO Voser has implied…”we’ve been here before…”

In a supply-constrained model, once you are at the carrying capacity price, then price will not increase to marginal cost, rather it will increase by GDP growth plus efficiency gains. (This is the essence of the debate between Jeffrey and myself above.) At present E&P costs are rising at 11% per year, and oil prices should have +/- 5% growth in them annually. So we have a mismatch in the pace of revenue and cost increases. In this world, if P is less than MC, then MC must decrease. As a practical matter, that means the oil companies get pushed off their projects. And that’s what we’re seeing. For example, Chevron just shelved the Rosebank project on cost concerns. (Goldman Sachs listed the project with a breakeven oil price of $68(!).)

Now, how can the oil companies respond to this reality? They can cut opex, which is hard, given that there is little slack in the industry and experienced labor is exiting rather than entering.

The can cut capex, which has begun in a modest way.

They can raise debt, which has so far proved not popular. Or they can cut dividends, but the trend is running in exactly the opposite direction as investors are demanding cash payouts.

Therefore, a short term step is to divest, and across the board the majors have substantial divestment programs. This includes Statoil, Hess, BP, and Shell, among others. This is fine, but of course they are divesting their revenues, and with that, part of their future cash flow, and with that part of their ability to fund future capex.

Now, all this is great if E&P costs start rising at a slower pace or oil revenues start rising more quickly. But it’s not clear that’s happening. And if it doesn’t, then this becomes just an on-going chain of divestments, followed by reduced operating cash flows, followed by reduced capex. Hence capex compression.

This has been apparent for some time, if you use a supply-constrained model. You’ll recall my comments of, say, November of last year, when I made statements to this effect.

To return to Shell: A divestment program of 17% of assets is huge. It’s not trimming around the edges, it’s a wholesale overhaul of the upstream portfolio. The thinking is that they’ll trade low value assets for high value new projects. But if costs are rising faster than revenues, then those new projects will not improve cash flow. So divestments are really something of a misdirection in a broader economic problem.

By the way, none of the oil majors use supply-constrained modeling. Not Shell, BP, Exxon, CP (maybe a bit–they did divest their refineries after I visited with them), Chevron or Total (well, maybe they use it a bit). Neither the EIA nor the IEA use supply-constrained modeling, although the EIA is reasonably well familiar with it, in part because I’ve presented there and we’ve discussed it informally a number of times.

So right now the oil companies are essentially flying blind. They don’t know why the oil price is what it is, why it’s not increasing, and whether it will in the future. But they can see that their upstream economics are deteriorating, and that they have to do something.

For example, Morgan Stanley’s equity analysts literally re-worked Shell’s whole strategy in an investor note in November, and a month later Shell announces these draconian restructurings.

Barclays, for its part, is projecting Chevron with negative free cash flow through 2017 averaging 4% of revenues. That’s unsustainable for more than another two quarters, so expect Chevron too to announce some significant divestments as well.

As for BP, they have been crippled by Macondo, their safety organization has (predictably) run amok and thereby hampered exploration and development work, and they are heavily leveraged to high capex projects like deepwater, the Arctic and oil sands. If you don’t think that revenues will begin to rise faster than costs, then BP is sitting on a portfolio of wasting assets, with less cash and operating efficiency than most of its competitors. Time is running against them, and the sooner they sell, the better the price. Meanwhile, Shell would likely desire an acquisition to make its own optics more attractive. In principle, we have a willing buyer and seller. I think it comes together soon, and both Goldman and Helge Lund, Statoil’s CEO, have been talking recently of industry restructuring.

In general, investors have responded well to cuts in capex and divestment programs, as these should improve short term financial performance. However, most investors are also using demand-constrained models and are therefore prepared to accept the notion that prices will rise to cover costs. That’s the story that the oil majors are selling right now, in part because they don’t have a better model, and in part because that’s about all they have for the moment.

Steven,

There’s a simple and straightforward model for declining US oil consumption: a demand curve from econ 101, which would suggest rising prices cause falling consumption.

The last time I looked at the EIA numbers, it appeared that the bulk of the decline came from industrial/commercial consumers: households are less price sensitive, especially when buying new cars, where the most affluent buy the cars, from which used-car buyers simply have to choose.

If consumption is rising now (which I suspect comes from the weekly reports, which needs to be confirmed with the revised monthly numbers), one cause would be tight oil production, which is using quite a bit of diesel for drilling and oil & water transportation, due to immature infrastructure (trucks and rail instead of pipelines).

Jeffrey,

The demand curves (which vary by industry and consumer) are not linear. Many consumers are price insensitive below a certain point (somewhere around $60/bbl), and become increasingly concerned above $100. Further, many consumers have taken a while to switch from short-term elasticity to long-term elasticity mode.

A long-term price above $150 (adjusted for inflation) is highly unrealistic, without some kind of major supply shock. Too many industries have alternatives which cost far less than that.

Already, water shippers are slowing down; truckers are installing aerodynamic modifications and switching to CNG/LNG; shippers are switching to rail; CAFE regulations are facilitating people getting better MPG; etc., etc. These substitutions will increasingly happen at *lower* prices, as new infrastructure is installed (e.g., charging and LNG pumping stations) and economies of scale reduce the cost of batteries and electric power trains.

Steven’s carrying capacity model conveys this non-linearity fairly well, and he has a point that above around $100 the world economy will have to recycle an increasing number of petrodollars, which it’s not all that efficient at.

JDH,

My take on the IOCs is that they are protecting shareholder value by reducing low-ROI capex. This will inevitably lead to falling production and a gradual closing of the company. If you feel that the world economy is dependent on oil production, that’s a disaster. If not, then it’s just “creative destruction” – capitalism business as usual.

Re: Nick G

I would argue that we are in the middle of a supply shock, since we have seen (in addition to a very slow increase in global crude oil production) a material post-2005 decline in Global Net Exports of oil (GNE*), with the developing countries, led by China, (so far at least, through 2012), consuming an increasing share of a post-2005 declining volume of GNE.

It’s instructive to review what has happened, from 2002 to 2012 for key net export and consumption ratios, versus annual Brent crude oil prices, which rose at an average rate of 15%/year from 2002 to 2012 (with one year over year decline, in 2009).

Normalized Liquids Consumption (2002 = 100%) for China, India, (2005) Top 33 Net Oil Exporters and the US, Vs. Annual Brent Crude Oil Prices:

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide14_zpsb2fe0f1a.jpg

GNE/CNI Ratio* Vs. Annual Brent Crude Oil Prices:

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide1_zps5f00c6e5.jpg

GNE/CNI Ratio* Vs. Total Global Public Debt:

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide2_zps01758231.jpg

*GNE = Combined net oil exports from top 33 net oil exporters in 2005, EIA data, total petroleum liquids + other liquids

CNI = Chindia’s net oil imports

What I define as Available Net Exports (or ANE, i.e., GNE less CNI) fell from 41 mbpd (million barrels per day) in 2005 to 35 mbpd in 2012. While there has been a rebound in US consumption, there is some question about how accurately the EIA is accounting for product exports in the short term, but in any case I would argue that the dominant post-2005 pattern, at least through 2012, was that developed net oil importing countries like the US were gradually being forced out of the global market for exported oil, via price rationing.

I agree with Steven that most countries fundamentally misunderstand what is going on in the global oil market, or probably more accurately, we are seeing denial on a global scale, what one writer called “The Age of Denial.”

To the extent that we have seen a rebound in the US economy and in US oil consumption, it’s important to remember how many trillions of dollars in deficit spending we have seen in recent years (largely financed by the Fed).

I think that the fundamental reality we are facing is that we are in the middle of a relentless transformation from an economy focused on “Wants,” to one focused on “Needs.” But governments in developed net oil importing countries refuse to acknowledge, or are incapable of acknowledging, this transformation, and they are desperately trying to keep their “Wants” based economies going via increased deficit spending, despite the post-2005 decline in the volume of Global Net Exports of oil available to importers other than China & India.

More thoughts on net exports follow.

Re: “Net Export Math”

As noted up the thread, I have continued to be surprised at how much attention is given to the top line production number globally, and not to the bottom line net export number, especially as the developing countries, led by China, have (so far at least) consumed an increasing share of a declining post-2005 Global volume of Net Exports of oil (GNE).

Of course, most economists would argue that all that counts is consumption and production, but on the other hand, everyone would agree, I assume, that net oil exporters can only (net) export what they don’t consume.

But here’s the problem. Let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that production in all net oil exporting countries is falling at a rapid clip (say 5%/year). If the net oil exporting countries do not cut their consumption at 5%/year, or at rate faster than 5%/year, the resulting net export decline rate will exceed the production decline rate, and the net export decline rate will accelerate with time.

Furthermore, what a simple model–and multiple case histories–show is that net export declines tend to be “front-end” loaded, to-wit, the bulk of post-peak Cumulative Net Exports (CNE) are shipped early in the decline phase.

In my opinion, we are only maintaining something resembling Business As Usual because of an almost totally unrecognized sky-high rate of depletion in post-2005 Global and Available Cumulative Net Exports of oil.

For a concrete example of how “Net Export Math” works, consider Mexico. I referenced a semi-hysterical Bloomberg column up the thread, about the prospect for vast amounts of oil coming out of Mexico in the years ahead, and as noted above, I am reminded about a 2009 Bloomberg column that talked about Brazil (a net oil importer with a recent track record of increasing net oil imports), “Taking market share away from OPEC.”

An Update On Mexico’s Net Oil Exports

In a February, 2013 article, titled “The Export Capacity Index (ECI):A New Metric For Predicting Future Supplies of Global Net Oil Exports,” I summarized recent global production and net export data, and I introduced what I call the Export Capacity Index (ECI), which is the sum of total petroleum liquids + other liquids production (per EIA definition) divided by liquids consumption for an oil exporting country. Net Oil Exports are defined as Total petroleum liquids + other liquids production less liquids consumption (EIA).

In the ECI article, I also reviewed what I called the Export Land Model (ELM), which is a simple mathematical model which examines what happens to net oil exports, given increasing internal consumption versus an ongoing decline in production in a net oil exporting country.

Based on the ELM, we can conclude that given an ongoing production decline in a net oil exporting country, unless they cut their internal consumption at the same rate as the rate of decline in production, or at a faster rate, the resulting net export decline rate will exceed the production decline rate, and the net export decline rate will accelerate with time.

Mexico’s production peaked in 2004 at 3.83 mbpd (million barrels per day, as defined above). Their 2004 liquids consumption was 2.07, resulting in 2004 net exports of 1.76 mbpd.

Their initial 2004 to 2005 rate of change in production was -1.7%, and their initial rate of change in consumption was +2.2%/year, resulting in a 2004 to 2005 net export rate of change of -6.7%/year. In simple percentage terms, a 1.7% decline in production, plus rising consumption, resulted in a 6.4% decline in net oil exports, from 2004 to 2005.

Their 2004 to 2012 rate of change in production was -3.4%/year, and their rate of change in consumption was +0.7%/year, resulting in a 2004 to 2012 rate of change in net oil exports of -11.1%/year.

In simple percentage terms, a 24% decline in production, plus rising consumption, resulted in a 59% decline in net oil exports, from 2004 to 2012, with net oil exports falling from 1.76 mbpd in 2004 to 0.72 mbpd in 2012.

Mexico’s ECI ratio, the ratio of liquids production to liquids consumption, fell from 1.8 in 2004 to 1.3 in 2012 (at an ECI ratio of 1.0, net oil exports would be zero). At the 2004 to 2012 rate of decline in Mexico’s ECI ratio, they would approach zero net oil exports in about six years. Note that Mexico in 2012 was the third largest source of imported crude oil into the US.

Based on the 2004 to 2012 rate of decline in Mexico’s ECI ratio, their estimated post-2004 Cumulative Net Exports of oil (CNE) are about 4.2 Gb (billion barrels).

Mexico shipped a total of 3.2 Gb in net exports from 2005 to 2012 inclusive, which suggests that Mexico’s post-2004 CNE are already about three-fourths depleted, which would be a post-2004 CNE depletion rate of about 18%/year through 2012, i.e., the rate at which Mexico is depleting their post-2004 cumulative supply of net oil exports.

This is completely consistent with what we have seen in other regions, e.g., Indonesia, as they approached zero net oil exports.

Note that Mexico’s net export decline was a contributor to the regional post-2004 decline we have seen in net oil exports. The seven major Western Hemisphere net oil exporters in 2004 were Canada, Mexico, Venezuela, Trinidad & Tobago, Colombia, Argentina and Ecuador, i.e., countries with in the Western Hemisphere with net oil exports of 100,000 bpd or more in 2004. Their combined net oil exports fell from 5.9 mbpd in 2004 to 5.0 mbpd in 2012. In other words, rising net oil exports from Canada have so far only served to slow the regional decline in overall net oil exports.

Link to ECI article:

http://www.resilience.org/stories/2013-02-18/commentary-the-export-capacity-index#

Jeffrey,

I agree that we are in the middle of a supply shock, that net oil exports (and imports) are falling, that oil is being allocated by price, and that many oil consumare are reducing their consumption.

But what does that mean? I would argue that’s positive for oil importers, especially the US. Oil isn’t magically necessary for the world economy: there are cheaper and better alternatives, and the sooner we switch away from oil, the better off we are.

We need to address an essential issue: external costs. Climate Change is very expensive. Oil wars cost in the range of a trillion dollars. Oil shocks have arguably cost trillions (each trillion costs about $3 per barrel consumed in the last 10 years). If we fully load oil with all it’s costs, we’ll find that it’s not nearly as cheap as we thought.

Supply shock? Oil markets are in the middle of a supply shock. I must have missed something.

Sorry, I see that it is a negative shock because net exports are declining? Did I get that right Jeffrey?

Strikes me that in some cases, net exports are down because domestic consumption is up. Isn’t that a shock to the demand side?

westslope,

Oil markets are in the middle of a supply shock because supply stopped growing around 2004, while the world economy continued growing. That meant prices rose from around $20/bbl to around $100 to balance supply and demand.

Net exports are declining because oil exporting countries shield their consumers from price reality. That means those countries use oil for sub-optimal consumption, instead of selling to the highest bidder, who likely would get far more value from it. That can’t last, of course, as declining net exports will eventually mean declining revenues. Subsidized fixed prices will have to break, and bring political trouble.

Global Net Exports of oil (GNE*), 2002 to 2012:

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide1_zps3161a25b.jpg

Available Net Exports of oil (GNE less CNI), 2002 to 2012:

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide04_zpsd68833b7.jpg

GNE/CNI Ratio, 2002 to 2012 (Showing extrapolated decline to 2030):

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide1_zps9ff3e76d.jpg

As noted above and as shown in the third slide, at the 2005 to 2012 rate of decline in the GNE/CNI ratio, in 17 years China & India alone would theoretically consume 100% of Global Net Exports of oil.

I suppose that one way to look at the data is that a lot of developed net oil importing countries might not have to worry about how to pay for their oil imports in future years.

*GNE = Combined net exports from (2005) Top 33 net oil exporters, total petroleum liquids + other liquids, EIA

CNI = Chindia’s Net Imports of oil

Nick G,

Subsidies in net oil exporting certainly do have a negative impact on their net oil exports; however, as noted above, given an ongoing production decline in a net oil exporting country, unless they cut their consumption at the same rate as the rate of decline in production, or at a faster rate, the resulting net export decline rate will exceed the production decline rate, and the net export decline rate will accelerate with time. Furthermore, if the rate of increase in consumption exceeds the rate of increase in production, a net oil exporting country can become a net importer, prior to a production peak, e.g., the US and China.

Consider two members of AFPEC (Association of Former Petroleum Exporting Countries), Indonesia and the UK. Indonesia subsidizes petroleum consumption, while the UK heavily taxes petroleum consumption.

Indonesia’s production (total petroleum liquids) apparently peaked in 1991, and they hit zero net oil exports in 2003. Here are the 1991 and 2002 production (P), consumption (C) and net export (NE) numbers for Indonesia (mbpd):

1991:

P: 1.7

C: 0.7

NE: 1.0

2002:

P: 1.3 (Down 24%)

C: 1.2 (Up 71%)

NE: 0.1 (Down 90%)

The UK’s production (total petroleum liquids) peaked in 1999, and they hit zero net oil exports in 2005. Here are the 1999 and 2004 production (P), consumption (C) and net export (NE) numbers for the UK (mbpd):

1999:

P: 2.9

C: 1.7

NE: 1.2

2004:

P: 2.0 (Down 31%)

C: 1.8 (Up 6%)

NE: 0.2 (Down 83%)

My point is that our global net export supply base consists of the sum of the output of net exporting countries that show net export declines like Indonesia and the UK.

Here is a graph showing the 2005 to 2012 rates of change in the ECI ratios* for the (2005) Top 33 net oil exporting countries:

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide1_zps5a656e89.jpg

26 of the (2005) top 33 net oil exporting countries are presently trending toward zero net oil exports (when the ECI Ratio = 1.0).

*Ratio of total petroleum liquids production (and other liquids for EIA data base) to liquids consumption

Jeffrey,

I don’t know why anyone would suggest that paying more for oil imports is a good thing.

If the US had properly priced oil products since WWII, cumulative and current imports would be much lower. Employment and GDP would be higher and debt would be much lower. Paradoxically, oil prices would be lower, and the final price to the consumer not much higher. But, the price premium would be flowing to the US, and not to oil exporters.

Both China and India are recognizing the self-destructive nature of price controls and subsidies, and are freeing prices and eliminating direct subsidies. That will reduce oil consumption and import growth, and strengthen their economies.

Last week’s decline in US natural gas storage was 177 BCF, versus 285 BCF the week before, for a two week average decline of 231 BCF/week. Storage at the end of last week was 3,071 BCF.

The natural gas market may be “interesting” by the end of the heating season. Note that the forecast high temperature for New Year’s Day in International Falls, MN is 12 degrees below zero.

As I have periodically noted, a recent Citi Research report puts the decline rate from existing US natural gas production at about 24%/year. This would be the year over year simple percentage decline in production if no new wells were completed in 2014. In any case, Citi estimates that we need 17 BCF/day of new production every year, just to maintain current production. This would require the productive equivalent of the peak production rate of thirty (30) Barnett Shale Plays over the next 10 years, just to maintain current US natural gas production for 10 years.

An item in today’s WSJ:

Natural-Gas Inventories Show a Shift in Market

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304753504579282442825702268

While not quite going from feast to famine, the U.S. natural-gas market suddenly looks a lot different.

Futures prices have soared of late to a two-and-a-half year high as cold weather caused a spike in heating demand, taking an unprecedented bite out of inventories. Last week’s report on underground gas stockpiles from the Energy Information Administration showed a drop of 285 billion cubic feet, shattering the previous weekly record established in January 2008. The report for the week ended Dec. 20, due Friday, should show a more typical reduction. . . .

It has been conventional wisdom in the industry that a glut of cheap gas from shale deposits would keep prices depressed for the foreseeable future. And it is odd that the record (285 BCF) draw came during a week that wasn’t nearly as cold on a population-weighted basis as when the 2008 record was set. The amount of gas available for heating demand may be lower than many analysts believed.

Nick G,

So by supply shock, you, Jeffrey and other mean a shock to the growth rate of supply. Perhaps you assume some kind of ‘natural’ steady state growth equilibrium and any deviation constitutes a ‘shock’.

I do not believe that this is the way economists typically think about shocks to supply and demand. It is ironic that the global production growth rates of a non-renewable resource are viewed as some kind of desirable equilibrium.

|

westslope,

That’s an interesting question. Professor Hamilton hypothesizes that the increase in oil prices before the Great Recession contributed substantially to the depth and timing of the recession.

For a long period (very roughly the 75 years leading up to 2004) oil was a relatively normal, buyer’s market. Oil supplies always exceeded consumption, and producers were obsessed with finding ways to constrict supply to support prices: the Texas Railroad Commission restricted supply until the 1970’s, when US production peaked. OPEC took over that function, though neither really tightened supplies or raised prices all that much, excepting the occasional embargo or war.

Since 2004 we’ve been in an unusual situation: a major commodity is in tight supply, so that prices rose by about 5x, and producers are unable to raise supply sufficiently to reduce them, let alone create the usual commodity boom ‘n bust cycle.

Oil exporters are rolling in cash, and oil importers are feeling a bit pinched, especiallly the PIIGS nations.

Finally, I agree about an “odd” equilibrium. I think that oil prices (and sales volumes) are well above a level that makes sense, given the potential for alternatives. But, that will take a little while to settle down to something stable. At the moment, we’re in a bit of a tussle between depletion, supply responses (especially in N. America), and the growth of alternatives.

Westslope is correct. We have had only one supply shock in recent times, and that was April 2011–the Arab Spring. Europe fell into recession, and to judge by gasoline consumption, so did the US (and yet, it didn’t. Why?)

Nick and Jeffrey are correct is arguing that supply has been unable to keep up with demand, which we can see clearly in the collapse of efficiency in upstream spend.

Thanks for the replies Nick G and Steven.

A few comments follow. I am not aware of any compelling evidence that oil price shocks (regardless of the source) have driven European economies into recession. Nor China.

Consumption and demand are not the same. On a couple of occasions I have read both Hamilton and Menzie use them as if they are interchangeable. In this case, it is rather clear that supply has been lagging ‘demand’ for quite some time if you somehow assume that low prices are a natural or optimal state of affairs.

If I understand Hamilton’s work, expectations work against oil price shock that follows within a few years of the previous shock driving the US economy into recession. Oil price spikes drive the US economy into recession because the portion of budgets allocated to fuel enjoy inertia and the overall budget shortfall is made up by post-budget cuts elsewhere. Those non-fuel decreases in expenditures throw the US economy into recession.

westslope,

I believe that there is a pretty decent correlation between oil import volumes and the level of distress of European countries. It stands to reason: high levels of imports will make a country subject to a sudden deterioration of trade balances when prices rise.

Low commodity prices are indeed a natural state of affairs: supply generally responds to price spikes, and boom and bust is a pretty standard state of affairs for commodity markets. Oil exporters like Saudi Arabia are now getting large amounts of “rent”: a premium due to unusual scarcity. It appears that new entrants to these markets will have to be non-traditional: electrification of transportation, etc.

My memory is that Hamilton argues that the Great Recession oil shock primarily suppressed car sales, due to consumer uncertainty. This reduction in capital expenditure depressed the economy. I’m actually not certain how much I accept this argument: car dealers will tell you they had many buyers who simply couldn’t get credit.