Recent indications are that, in the face of declining inflation, ECB President Draghi is considering embarking upon quantitative easing. Despite the technical difficulties accompanying such a measure [0] [1] I believe additional stimulative measures are nonetheless called for.

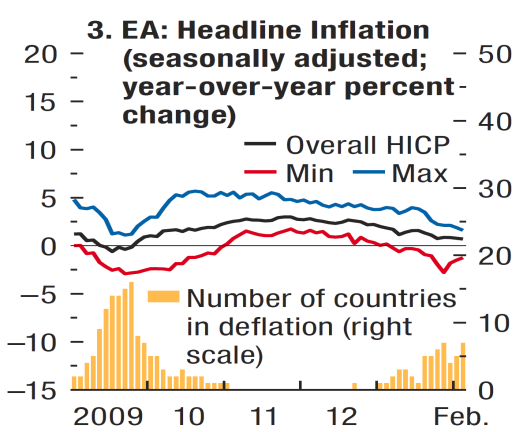

This figure from the recently released World Economic Outlook (p.55) demonstrates that while the overall euro area inflation rate is still (barely) positive, the minimum inflation has clearly dipped into the negative region.

Figure 2.3.3 from IMF, World Economic Outlook (April 2014), p. 55.

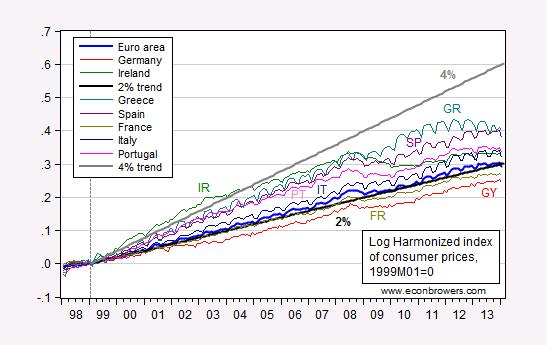

Not only is deflation occurring in the periphery countries, from one perspective, the need for higher short term inflation extends even to countries not experiencing deflation. Figure 1 depicts the euro area price level, as measured by the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), as well as the levels for several individual countries within the euro area, all normalized to 1999M01=0.

Figure 1: HICP for euro area (bold blue), Germany (red), Ireland (green), Greece (teal), Spain (purple), France (olive), Italy (dark blue), Portugal (pink), 2% growth line (bold black), and 4% growth line (bold gray). Source: ECB, and author’s calculations.

Giannoni and Harmen argue that in the case of the United States, the Fed, by virtue of a long term 2% inflation target, has effectively implemented a two percent price level target. In some sense, the same appears true for the ECB and the euro area. Figure 1 indicates that the euro area wide HICP has followed the 2% price line (disturbingly, the overall HICP has dipped below the 2% line).

At this juncture, the distinction between the US as a monetary and fiscal union with high interstate factor mobility, the euro area as a monetary union with relatively low inter-country factor mobility, becomes important. While inflation is negative in the periphery countries, the deviation from the trend line is negative for the core (and large) euro area countries of Germany and France. The German deviation is about 5% in log terms. While the French deviation is smaller in absolute value, it contrasts with the pre-crisis value of essentially nil. If nominal debt had been accumulated with the expectation of the two percent trend in the price level, the very fact that the price level is lagging implies higher than expected debt burdens and hence more binding collateral constraints.

The IMF concludes:

Macroeconomic policies should stay accommodative. In the euro area, additional demand support is necessary. More monetary easing is needed both to increase the prospects that the ECB’s price stability objective of keeping inflation below, but close to, 2 percent will be achieved and to support demand. These measures could include further rate cuts and longer-term targeted bank funding (possibly to small and medium-sized enterprises). …

Unencumbered by institutional constraints, I would argue for even more forceful measures, aiming for a higher inflation target. In fact, by a 4% price level target (roughly equivalent to a 4% long run inflation target, as mooted by Blanchard in 2010 [2]), the periphery countries (aka GIIPS) should be aiming for a higher trend inflation rate.

In addition to reducing the likelihood of encountering the liquidity trap [3], and heightening the credibility of future inflation during periods of deflation [3], a steeper price level target allows for better relative price adjustment. This last point is critical given the conditions of the euro area, which include downward price rigidities (specifically, it is easier to have prices in country A rise by 5% and those in country B stay constant, than a 3% rise and 2% decline, respectively).

In other words, we need higher inflation now!

Menzie

Would you go a step back? What is the actual rule the ECB operates under? Is it the same as the the dual mandate US Fed, inflation and employment, or does differ and if so how?

Ed

Ed Hanson: The ECB has a price stability mandate, currently interpreted as 2% inflation or less using HICP.

Thanks Menzie,

I will toss out a question, how would you answer it.

If monetary policy were an exact science, and central banks could instantly manipulate money such that at all times inflation (and deflation) were 0, Would this be a good thing?

I would answer yes, as people expectations, their planning, long and short, would have one major element known.

But of course, it is not such an exact science, so as a safety factor, well operating central banks have settled on a 2% inflation target to give them time to react when policy does not work as expected, and can change.

But that is not what is being proposed here, not an additional safety factor but simply out and out inflation as if its illusion is a good thing.

I have to admit that I find statements such as “Although downside risks have diminished overall, lower-than-expected inflation poses risks for advanced economies, there is increased financial volatility in emerging market economies, and increases in the cost of capital will likely dampen investment and weigh on growth.” (italics mine for emphasis)( IMF World Economic Outlook April).

Downside risks – IMF -good, ME – good, Most People – good

lower than expected inflation – IMF – bad, ME – good, Most People – good

Increased financial volatility, emerging markets, IMF – bad, Me – So what’s new about this, (and by the way, IMF do your job better or get out of the business), Most People – so whats new about this (and what is this IMF)

The history of economies and empire through out the world is the story of stable money, lesser government power, and growth, followed by greater government power, lesser growth and finally unstable money through debasing the currency.

Time and time again, powerful governments refuse to surrender control, keeping tax rates high and resorting to the false hope of inflation.

I suggest that this is the pattern that again is appearing.

Ed Hanson I think you’re contradicting yourself. At the very beginning you seemed to agree that stable and predictable prices are a good thing. But if that’s what counts, then there really isn’t much difference between a perfectly controlled and maintained 0% inflation rate and a perfectly maintained and controlled 2% inflation rate. In both cases expectations are known perfectly. Then you go on to say that lower than expected inflation is a good thing. Huh? This last statement completely contradicts the premise behind your earlier comment. It’s consistency with expectations that counts, not the number itself.

I’m sure Menzie can provide a better answer to your question than I can, but my take is that the reason a 2% inflation target is better than a 0% inflation target is that the Fed cannot perfectly control inflation. This is a problem because the risks of unexpected inflation shocks and unexpected deflation shocks are not symmetric. They are not symmetric for two reasons. First, inflation is fairly well understood and we have a plethora of policy tools and decades of research that can inform policy direction. That’s not the case with deflation. Deflation is a much more difficult beast to fight than inflation. Second, the consequences of greater than expected inflation are relatively benign compared to the consequences of deflation. Inflation primarily affects income classes that are better able to absorb the loss. Inflation hurts savers and eventually hurts capital accumulation. That’s not a good thing, but it’s a lot better than deflation, which primarily affects low income debtors who are less able to absorb the loss. This hurts aggregate demand, which also eventually hurts savers and capital accumulation. You don’t want either unexpected inflation or deflation, but if you have to choose between the two, inflation is by far the lesser of the two evils.

My reading is that Menzie’s comment, “…we need higher inflation now!” has two meanings. The first meaning is that Europe needs higher actual inflation just to bring it up to the 2% target. The second meaning is that the inflation target itself should be raised to (say) 4% because the 2% target doesn’t provide a wide enough safety zone. You don’t want to set the target too high because higher targets might be unstable, but you don’t want targets that are too low either.

There are two arguments for inflation higher than zero: getting money out of mattresses, and allowing real prices to drop where nominal prices are “sticky”.

I think what all folks here forget, is that it is completely irrelevant what some alien english speaking economists say about funny theories of OCA.

The law says , no bail out and price stability.

Soo, the agreed upon mid term rate is still significantly above target, and that would make any further instigation an agression on the founding treaty,

treason : – )

Slug

To the point, we read Menzie different, he is advocating higher inflation than 2%. I believe that is obvious.

I simply refer to history that governments time and time again resort to inflation (debasement) rather to return to policies that created wealth to begin with. Inflation is an illusion wealth creation. Real wealth creation comes from opportunity. As power concentrates into government which manifests in high tax rates and regulation opportunity is lost. Simply put, history governments will choose illusion than to reduce its own power. Menzie would make that same choice.

By the way, I just noted the reference to a Chinn and Frieden paper at the end of the post. I intend to read it when I have time.

Ed

Ed,

I’d be curious about specific examples of such historical governments.

Ed Hanson You’re confusing the inflation rate and the uncertainty of the inflation rate. The opportunities for seignorage are limited by the government’s ability to generate surprise or unexpected inflation. Expected inflation is fully captured in contracts and interest rates, so from that perspective it does not matter whether the inflation rate is 2% or 20% as long as it is anticipated and controlled at that level. If actual inflation matches expected inflation, then the government’s opportunity to enjoy seignorage vanishes. Menzie is arguing for a higher inflation rate, but I don’t think he is arguing for Fed or ECB mendacity. I think you are misreading his post.

You’re also oversimplifying history. While some governments have resorted to seignorage in order to consolidate political power (e.g., Tudor England), you can find just as many governments that used deflation to consolidate political power (e.g., late Roman era Gaul and 5th century Hunnic powers along the middle and lower Danube). A more modern example would be rentier dominated governments like Gilded Age America.