The spectacular drop in oil prices means that inflation is going to fall even further below the Fed’s 2% target. Does that raise any new risks for the economy? I say no, and here’s why.

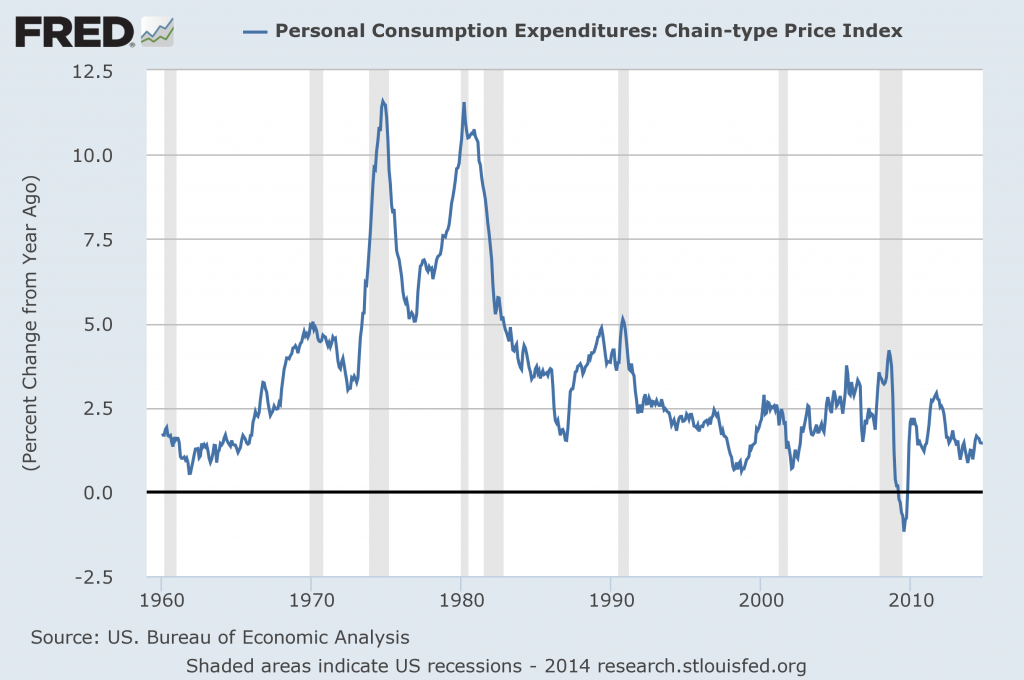

Year-over-year percent change in the monthly deflator for personal consumption expenditures. Source: FRED.

In economists’ theoretical models, inflation usually is often thought of as a condition in which all wages and prices move up together by the same amount. For a given nominal interest rate, the lower inflation, the higher is the real cost of borrowing. With the short-term nominal interest rate still stuck at zero, a decrease in inflation could discourage spending, something the Fed would rather not see happen in the current situation. Or so the theory goes.

But typical consumers often have something very different in mind when they talk about inflation. Many people think of inflation as a condition where the cost of the goods and services they buy goes up but their wages do not. Not so surprising then that while the Fed says it wants more inflation, most consumers say they do not.

What’s happened to oil prices this fall looks more like the average Joe’s version of reality than the Fed’s. The average U.S. retail price of gasoline right now is about $2.40 a gallon. Last year American consumers and businesses bought 135 billion gallons of gasoline at an average price of $3.60 a gallon. If gasoline prices stay where they are and if we buy the same number of gallons of gasoline this year as last, that leaves us with an additional $160 billion to spend over the course of the year on other items. If we restate the total savings for U.S. consumers and businesses in terms of the 116 million U.S. households, that works out to almost $1400 per household.

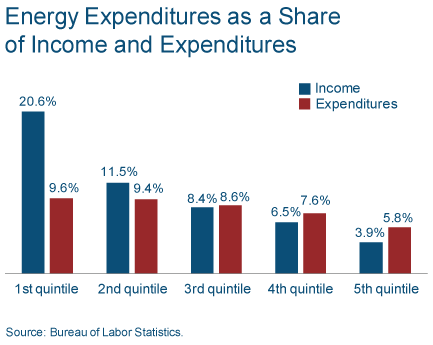

It’s a particularly big deal for the lower-income households, who spend a much higher fraction of their income on energy.

Source: Daniel Carroll.

Historically consumers have responded to windfalls like this by becoming more open to the big-ticket purchases that play a huge role in cyclical economic swings.

So no, any deflation associated with the gasoline price drop is not going to discourage aggregate demand. What it does do, however, is give the Fed a little more time to be patient before it needs to worry about raising interest rates.

In this case, I would quibble about the “windfall” notion in favor of modeling this as a shift in the basket of goods bought for income constrained consumers, with less-income constrained consumers bringing durable purchases (and the like) into the present.

It’ll raise real income and generate demand.

The economy needs a self-sustaining consumption-employment cycle (where consumption generates employment and employment generates consumption, etc.).

It’s uncertain if lower oil prices are powerful enough, and long-lasting, to spur that cycle.

We also needed a large tax cut, substantial deregulation, and gradual minimum raise increases.

Meant gradual minimum wage increases.

As far as I now the Fed targets PCE ex food ex energy, and is therefore unaffected by the oil drop, but might watch carefully any 2nd order spillovers to over places.

The ECB targets HICP, incl. food and energy, but with taxes being 60% of the total gas price as recently as 2 month ago, crude price has much less of an impact.

And the food supply in the European union is much more diversified than in the US, especially wiht regard to weather, beyond base stables like flour, rice, sugar.

The BuBa, the holy German Central Bank has already announced, correctly, that a few months of tiny negative rates are of no concern at all

http://www.welt.de/newsticker/bloomberg/article135433480/Weidmann-lehnt-Staatsanleihekaeufe-ab-selbst-bei-Deflation.html

We, the German people, and our allies, the northern majority in the Euro area, reject QE a.k.a. as “bail out” a.k.a. monetary financing as treaty violations, unconstitutional, CRIMINAL. We have already sacrificed “die harte deutsche Mark” http://www.titanic-magazin.de/uploads/pics/card_691558056.jpg

Just one step further, and I will have to think about the military draft reactivated, and will massively promote for one hell of a economic stimulus by doubling or tripling our military expenses within one or 2 years.

For treaty text (“THE LAW”) discussion of it, links, and the usual sloppy american economics professor reply see my comments at http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2014/12/the_ecb_is_it_a.html#335540 and above there

Anyone tempted to read what genauer wrote about the law via his link should certainly read Scott Sumner’s response to genauer in a subsequent comment. Sumner reveals the usual sloppy German thinking about EU law as it relates to inflation. Genauer’s comments here and there may represent a common view among his countrymen, but they are misleading regarding the actual law.

Macroduck,

for you holds the same as for Scott Sumner there:

to call, again here, my verbatim citation of referenced ECB text “misinformation”, that is really gross, and sloppy.

And his response was to the PRIOR, not subsequent comment.

I really dont want to make, especially unpleasant, cross talk between different blogs a habit, but in this exception :

I already had to correct him on the next incorrect claim http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2014/12/markets_describ.html#335665

But please feel free to explain to us here, where I went wrong SPECIFICALLY on european treaty texts and data.

Falling oil prices ARE deflation. The questions you apparently are posing are 1) whether oil price deflation might lower price inflation averages such as CPI and PCE inflation below zero, and 2) if so, would that be a problem. My answers are 1) possibly, but only slightly and briefly, and 2) not at all.

The theory that deflation in and of itself is something to be feared is wrong and needs to be debunked and discarded. Deflation might be a symptom of something negative, such as contracting output or a financial implosion, or it might be a symptom of something good, such as increasing productivity.

There’s something very wrong with the usual analysis that deflation hurts spending by raising real interests. Namely, it leaves out that deflation also raises real incomes. Borrow-to-spend decisions are made mainly on the basis of nominal interest rates and anticipated nominal future incomes, much less on anticipated future prices.

Too glib. The effect of deflation on nominal debt burdens is widely discussed, but you have not addressed it directly. Your discussion of debt decisions asserts a model which offers, at best, a hand-wave regarding this critical issue.

If you want tobe taken seriously, you need to address the effect of deflation on debt burdens explicitly.

Again, you are confusing price deflation with income deflation. Income deflation increases debt burdens. Price deflation decreases debt burdens, by freeing up income that can be used to repay debt. An oil price decline is a price deflation. Since it’s resulting from increased productivity, namely of oil, it poses no threat of income deflation.

Also, keep in mind that arguably only unexpected income deflation really increases debt burdens. Anticipated income deflation was part of the real interest rate at which the funds were borrowed.

Prices are someone’s income. When commodity prices fall, some consumers benefit, but producers take a hit. Eg. The effect of low corn/soybean prices on farm income.

Of course. But if the producers of the good that’s falling in price are also increasing productivity, they’re income might not fall. That is how manufacturers of automobiles and most kinds of electronics make money even though their products are deflating in price.

If you’re looking for a deflation hit to the US economy from falling oil prices, it’s the coming slowdown in investment and production growth in the oil sector, maybe even a production decline.

But the losses the oil sector will take are also a wealth transfer to consumers, who are likely to use that extra wealth to spend on other things, including other domestic goods and services. Which is likely to boost growth in other sectors, especially since we still have substantial labor slack. And the drop in prices on net oil and oil product imports is a pure gain for the US economy. It’s likely to cut around $100b off our annual import bill.

manufacturers of automobiles …their products are deflating in price.

Have you seen data that car prices have fallen? AFAIK, they’ve added features, but not lowered real prices. That’s better value for the money, but I wouldn’t really describe it as “deflating in price”.

Debt is not a problem, you say. We owe it to ourselves. How then, I say, can the effect of deflation on debt be a problem? We’d simply owe the effect to ourselves, I say. Oh, you say, in certain circumstances debt can be a problem. We’ve just waved our hands over that all these years. In fact, debt acquired in the past can be troublesome when deflation strikes. So never for a moment can we allow deflation. Oh, I say, now you say debt is a problem. Then why not directly go after the primary problem of too much debt and leverage rather than beating up on poor deflation, I say? We don’t treat the primary problem of too much debt, you say, because debt contains the benefit of allowing us to spend beyond our present means so as to be at full employment. Oh, I say, you’ve convinced me. We should then, I say, create even more debt to stave off the derivative problem that can arise with deflation when too much debt exists because debt has such wonderful benefits even though it is the primary problem. Yes, you say, now you’ve got it. And so, I say, following up on that it would seem that each additional increment of debt makes the problem of deflation recede further until that problem vanishes altogether. Yes, you say, now you’ve got it. But what about debt service, I say? Doesn’t future debt service on the extra increments of debt taken on to deal with potential deflation have to come out of the flow of future income leaving less for saving? Your whole solution, I say, seems to require relinquishing a claim on future income simply to have enough to meet the growing debt service obligations you’ve taken on with the additional debt used to ameliorate the secondary deflation problem and in the process create an incrementally increasing shortfall of savings. Saving, you say, is not the important point. We don’t really have to save because we can always borrow to purchase whatever it is we need the savings for. From whom, I say, do we borrow? Why, you say, we borrow from ourselves. Isn’t that, I say, a lot like owing the debt to ourselves? Yep, you say, now you’ve for sure got it.

This leads me to a question I’ve never seemed to have received a decent explanation to. Inflation is wages& prices going up, what’s the problem? I can understand the aversion from the consumer’s perspective if it’s only goods&services with wages stagnant. Maybe a bit more insight on the differences between the economist’s views vs. the consumer’s that you mentioned.

One of the main risks of deflation is that the nominal value of assets tend to fall under deflation, because the nominal revenue stream falls. The nominal value of outstanding debt used to purchase assets does not fall. As a result, debt burdens rise under deflation, interfering with the credit channel. Defaults become more likely and potential borrowers become less willing to borrow. Negative or near zero ominal rates are needed, but entail additional balance sheet risk for lenders.

Deflation creates a mess for finance.

It’s about nominal growth = real growth + inflation.

There’s the Keynesian concept of “sticky prices” with deflation, i.e. prices may not fall enough to maintain real growth.

And, some inflation provides a “buffer” for monetary policy to promote growth.

Moreover, it’s important to facilitate “animal spirits,” through price stability.

Here’s a Bill Gross interview from Jan ’07:

Bloomberg’s Tom Keene: “…As you know, I’m a big fan of nominal GDP – this, folks, is real GDP plus inflation. It’s the ‘animal spirits’ that’s out there. You say be careful, Bill Gross. It looks real good to me, Bill. I see 6% year-over-year nominal. You say that’s going to end?”

Pimco’s Bill Gross: “…Ultimately, the inflation component affects the real growth component. To the extent that you have nominal GDP – in my forecast 3 to 3.5%, that’s really not enough growth in terms of the economy itself to support asset prices at existing levels. And so, declining assets prices ultimately factor into eventually lower real growth. But that’s not for mid-2007 but perhaps for later in the year.”

Tom Keene: “When we look at six months of low nominal GDP, is that enough to link directly into the ‘animal spirits” of the business investment component of GDP – the “animal spirits” of business men and women?”

Bill Gross: “Well sure it is. When you realize that the average cost of debt in the bond market – and therefore in the economy and this includes mortgages – it is about 5.5%. If you can only grow your wealth and service that debt at 3.5% rate, then that has serious implications.

When you go back to 1965, Merrill [Lynch] did this study – in terms of asset prices during periods of time when nominal growth grew less than 4%. Risk assets have been negative in terms of their appreciation and actually bonds have done pretty well. The question becomes why hasn’t that happened yet, and I think we’re simply in a period of time where there are leads and lags that are much like the leads and lags of Federal Reserve policy.”

EconStudent: In many economic models, inflation that is perfectly anticipated works just as you describe– everybody goes about their business just as they would otherwise. One important exception is when, as now, the short-term interest rate is stuck at zero. In this environment, a fully anticipated change in inflation means a change in the real interest rate. However, my view is that the most important dimension of recent developments is that it is a relative price change that works to the advantage of consumers and to a net oil importing country like the United States, and this outweighs any other considerations. In addition, I think the psychology of this kind of change works differently from the textbook model of changes in inflation.

It is important to distinguish between measured deflation and actual deflation along with deflation/inflation expectations.

Jim,

“If gasoline prices stay where they are and if we buy the same number of gallons of gasoline this year as last, that leaves us with an additional $160 billion to spend over the course of the year on other items.”

You’re assuming (at least implicitly) a vertical demand curve, no? I agree that that’s a pretty good short-run approximation, but to the extent that’s not true, your windfall calculations will be smaller. My prior is that this effect could also matter most at the low end of the income distribution. If I had a grad student I’d be tempted to have her/him look into this…

PS

Peter – See slide 8

http://www.eia.gov/conference/2014/pdf/presentations/pickrell.pdf

Thanks Steven! That’s very helpful.

PS

Great post.

Low oil prices will lead to lower inflation as a first respond due to low transportation cost , fule cost and matrrial cost. I gree that barowing will be reduced from middle and low income classes yet, high class and companies will stay the same. Banks should not have much increase in the intrest rates with this condition. After sometime inflation will have small increase that is acceptable. I do agree with you of government comtrol the banks intrest rate.

Tom,

You really need to go back to the drawing board on your concept of deflation. Do you consider the decline in computer prices from 1980 to the present as deflation? Falling prices are not deflation. They can be caused by technological improvements in products, better delivery methods and other production productivity gains and many other things. Deflation in a monetary sense is an increase in the purchasing power of money. To paraphrase Milton Friedman it is a monetary event. Just think about what we are writing.

Shouldn’t there be a role for rational consumer expectations with respect to how long gasoline prices are likely to stay low? In this case I think JDH’s “Joe Average Consumer” (or more likely “Josephine Average Consumer”) is likely to notice a few extra unclaimed bucks at the end of the week and then decide to take the kids to the movies, splurge on an overpriced coffee while Xmas shopping or some other small indulgence. I don’t see consumers suddenly deciding that it’s time to forget about buying a new economy car and buying a gas guzzler instead. That might happen if gas prices stay low long enough that consumers see cheap gas as here to stay, but at this point I don’t think many people believe that cheap gas is anything but a blessing with a shelf life. I don’t think the average consumer sees lower gas prices as a $1400/yr windfall. Instead, they see it as an extra $27 bucks a week, or a night out for pizza. They are unlikely to save it and instead reward themselves with small pleasure. In fact, just a few weeks ago JDH suggested that low oil prices were transient and should return to more normal levels. Isn’t it fair to conclude that Joe/Josephine Average Consumer believes that as well? And that’s really why the Fed shouldn’t be concerned about low gasoline prices leading to deflationary concerns. In the Fed model what counts are expectations, and I don’t think anyone believes today’s lower gas prices are anything other than a nice holiday gift that will be gone soon enough. And of course it will all be Obama’s fault.

There’s a lag, Slugs. Behavior changes incrementally pretty fast, more generally in about 12 months.

Some evidence is here: http://www.timesfreepress.com/news/business/aroundregion/story/2014/dec/07/truck-suv-sales-hit-a-new-high-mark/277026/

Steven Kopits I’m not sure you’re understanding my point. Prior to the recent drop in gasoline prices, the average price since March 2011 (almost four years) was around $3.50/gal plus/minus around $0.25/gal (source: FRED database). So any increase over the past year in SUV and light truck sales would reflect a combination of two things: (1) an improving economy, and (2) relative confidence that gasoline prices had stabilized around $3.50/gal so that people planned their vehicle purchases around that cost. That is clearly not what is happening now. Unless consumers are hopelessly irrational they should still expect gasoline prices to go back up to $3.50/gal in the not-too-distant future. Anyone who is buying an SUV or light truck today under the illusion that gas prices will stay at $1.94/gal over the long run is clearly delusional and in need of family intervention.

One angle that JDH didn’t touch on was the potential for a negative wealth effect as a result of lower oil prices that might offset some of the other effects he mentioned. A lot of people’s 401k portfolios could take some pretty big hits as asset prices jockey around and rebalance. There’s been a fair amount of volatility in the market recently…much of it due to what’s happening in the oil markets. Excess volatility is seldom a good news story for the average Joe/Josephine investor.

The US is still a considerable net oil importer, so low oil prices help us net. And keep in mind, we’ll still need more shale production.

As for SUV sales, keep in mind that we’re talking about marginal, not average, consumers. So there’s that guy who would like an SUV, but just can’t quite accept the fuel consumption. So the oil price comes down a bit, and he buys an SUV. Also, SUVs cover a number of sins. A Honda CRV is an SUV, but it’s built on the Honda Civic platform. Not all SUVs are the same.

Steven Kopits I don’t think anyone (except perhaps Katie Couric) denies that we’re a net importer of oil. And yes, lower oil prices are good news for those in the bottom quintiles. For those toward the upper end of the income scale it’s not quite so clear that lower oil prices make them better off. For those folks volatility movements in their 401k plans and portfolios almost certainly swamp any savings they might see at the pump.

So the oil price comes down a bit, and he buys an SUV. But you’re missing my main point. “Marginal Joe/Josephine” consumer is not going to change his or her purchasing plans for big ticket items unless he or she believes gasoline prices are going to stay low for an extended period. If people believe the price drop is only temporary, then purchasing decisions are likely to match the ephemeral nature of the windfall. That’s why the extra $27 a week is more likely to go towards pizza night or the movies then it is towards a new SUV. Now if that $27 a week windfall persists well into summer, then consumers will adjust their large ticket purchasing choices. But does anyone seriously believe $1.94/gal gasoline is the new normal? It’s not the price today that counts, it’s what consumers expect the price to be in the future.

If I look at the futures market, oil stays around $70 for some time. So marginal consumer is not irrational by this standard.

Steven Kopits So is JDH irrational in his belief that the long run equilibrium price for oil should be around $85/barrel? To quote from JDH’s post from 30 November:

So here’s the basic picture. The current surplus of oil was brought about primarily by the success of unconventional oil production in North America, most new investments in which are not sustainable at current prices. Without that production, the price of oil could not remain at current levels. It’s just a matter of how long it takes for the high-cost North American producers to cut back in response to current incentives. And when they do, the price has to go back up.

Here’s my advice to anybody who’s contemplating selling $85 oil at $66 a barrel– don’t do it. If you can wait a few years, that $85 oil will be worth more than it costs to produce. But selling it at a loss in the current market is a fool’s game.

I take the plain meaning of his comment to mean that what we’re seeing today is transient, and when the market corrects itself we should see prices return to more normal levels.

If you read what I’ve written here (http://www.prienga.com/blog/2014/12/10/exxon-calls-peak-conventional-oil), you’ll see my views are largely aligned with Jim’s. However, there’s some uncertainty as to how much shales can produce, and at what price.

So, shouldn’t we all be going long in oil futures??

EconStudent,

Let me address your question with an answer you probably will not hear from most academics. One of the most overlooked phenomenon in aggregate accounting is the Cantillon effect. The 18th Century economist Richard Cantillon wrote that when money enters a market it does not enter uniformly and; therefore, prices do not respond uniformly. To expand on Cantillon’s observation, in/de-flation do not enter an economy uniformly across all sectors, but are dependent on the economic environment. Normally, the Cantillon effect refers to injecting money into an economy. Consider how the FED does this. They usually buy bonds from banks. The money then enters the loan market first of those segments of the economy that are more sensitive to loans, for example real estate, are impacted before less interest dependent segments, such as services.

If we apply this to the fall in oil prices we can see that those industries more dependent on oil products will be impacted before other segments. This causes a dislocation where industries, such as transportation gain before other segments. How? Transportation costs decline (the cost of fuel) but transportation prices remain high. Until the effects of supply and demand spread the effect through the economy certain segments make windfall profits.

As you continue your economics education think about the Cantillon effect as your teachers give you information. You will find that often ignoring this effect can change results dramatically.

This is a good point and is holding true particularly for airlines. But the biggest oil consumers in the US are households, so the biggest windfall goes to them.

Also your characterization of QE is incorrect. The Fed bought Treasurys and agencies from government and Fannie/Freddie, via brokers. However the Fed didn’t affect the government’s spending or Fannie/Freddie’s lending; it didn’t change fiscal or quasi-fiscal policy. The effect was that instead of public authority printing new bonds, swapping them for existing cash and spending or lending that cash, public authority printed new cash and spent or lent that cash (while also printing bonds and holding on to them, which could be swapped for privately held cash later). Tracing how QE was spent misses the point. QE changed how public authority financed itself, not how public authority spent and lent.

EconStudent,

As you continue your education, you’ll want to watch out for claims that there is some economic phenomenon or other that economists don’t grasp or don’t talk about. While that is certainly true in some cases, claims about this point are often wrong. In this case for instance, Ricardo says that economists (academics) overlook the Cantillon effect. In fact, Jevons and Wicksell both took account of Cantillon’s ideas in there own contributions to economic theory, and of course, Wicksell and Jevons are foundational tomuch that has come since. The notion of leading sectors is, to a large extent, built on the idea that some sectors respond to swings in credit availability more quickly than others. You will see the connection to monetary policy. It may be that Cantillon’s name isn’t well known, but it’s pure bunk to claim that his ideas are neglected.

The Fed has been able to mask deflation for a few years by printing trillions but now that QE is over real prices and demand are becoming easier to see. The Fed’s newly created money in order to get into circulation. It was used by the 1% to speculate in assets and commodities while main street didn’t see a dime due to poor credit or lack of desire to borrow. Now we have sky-high asset and commodity prices with weak demand due to wage stagnation to decline for the last several decades. The result is prices crashes as recently seen in oil. This is just the start. I recently finished a book that predicted this called: Deflation, The Seismic Shift In Finance. It think its on Amazon.

If you look at energy and autos as a share of nominal personal consumption the sum of these two items is close to being a constant. In other words, if energy’s share of consumption falls two percentage points you would expect auto’s share to rise two percentage points.

This implies that the auto industry may be the greatest beneficiary of lower oil prices. Interestingly, us auto sales are almost back to a 0.7% long term trend growth rate established before the Great Recession. So maybe the strong cyclical rebound in auto sales is ending and auto sales growth is set to slow sharply.

“Many people think of inflation as a condition where the cost of the goods and services they buy goes up but their wages do not. ”

With good reason. Wages tend to be sticky on the way down. Deflation tends to translate into a pay raise for Joe Average. By contrast, automatic COLA is uncommon. The bank deliberately tries to avoid provoking automatic COLA, because it led to a wage/price spiral in the 70s. Joe tends to experience inflation as a pay cut in the absence of a true automatic COLA..

Retirees in particular tend to experience inflation as a pension cut. Few private sector pensions have automatic COLA, and retirees have little bargaining power with employers they no longer work for. Even the PBGC does not COLA pensions, and no one offers automatic COLA for 401k/IRA plan balances.

jim, nice article.

from your analysis, you indicate a drop in price of gasoline is not harmful and may be beneficial overall because people at the lower income levels will now have extra money to spend in the economy. basically this is a targeted redistribution of income. implied in this argument is that profits made by the oil companies are not efficiently reintroduced into the economy, at least in real time, compared to equivalent consumer spending.. lower income folks seem togrow the economy better than corporations-or at least gasoline companies-on the margin. stretching this a little bit, this is very similar to a targeted tax redistributed to lower incomes over short time period, no?

Here’s a post I wrote with Menzie in mind.

As all of you know, I take an oil-driven view of the economy (under supply-constrained conditions). I have argued that US GDP should return to long-term trend if the oil supply is unconstrained.

Well, we now have a model for that recovery, using air traffic as a proxy and following its gains after the collapse of oil prices in 1985.

Bottom line: GDP recovers trend by 2017/2018, implying GDP growth 1.5% (maybe more) above normal in the interim assuming (and this is a big assuming) that oil remains cheap. Here’s the post: http://www.prienga.com/blog/

And Bill McBride confirms the hypothesis. http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2014/12/q3-gdp-revised-up-to-50.html

I am beating Bill by minutes to hours right now. Not easy. It’s like playing the Seahawks of the econ stats world.

Sorry, but it does the opposite. It will raise core inflation while total inflation drops. This is exactly what central banks love. It also makes borrowing more attractive because you can pay down more debt…………….

The post answers no to the question in the post title.

Is there a possibility in USA of the occurrence of benign deflation rather than harmful deflation.

Professor Hamilton,

Do you have a time series forecast for Brent oil for the next twelve months that you could share with us. It seems if dlog(oil) is the dependent variable, there may be an AR(1) AR(6) model that has some possibility for the short-term for the average monthly price from 2000 to the current time.

Just one silly question: how do come to the conclusion “American consumers and businesses bought 135 billion gallons of gasoline” from the EIA data? Which voices are you adding? Thank you for your help and kind regards, MV

Marco Valerio: 3.23 B bl x 42 gal/bl = 136 B gal.

Thank you a lot, Marco Valerio LP