Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Laurent Ferrara (Banque de France), Ignacio Hernando (Banco de España) and Daniela Marconi (Banca d’Italia), summarizing the introductory chapter of their book International Macroeconomics in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis. The views expressed here are those solely of the author and do not reflect those of their respective institutions.

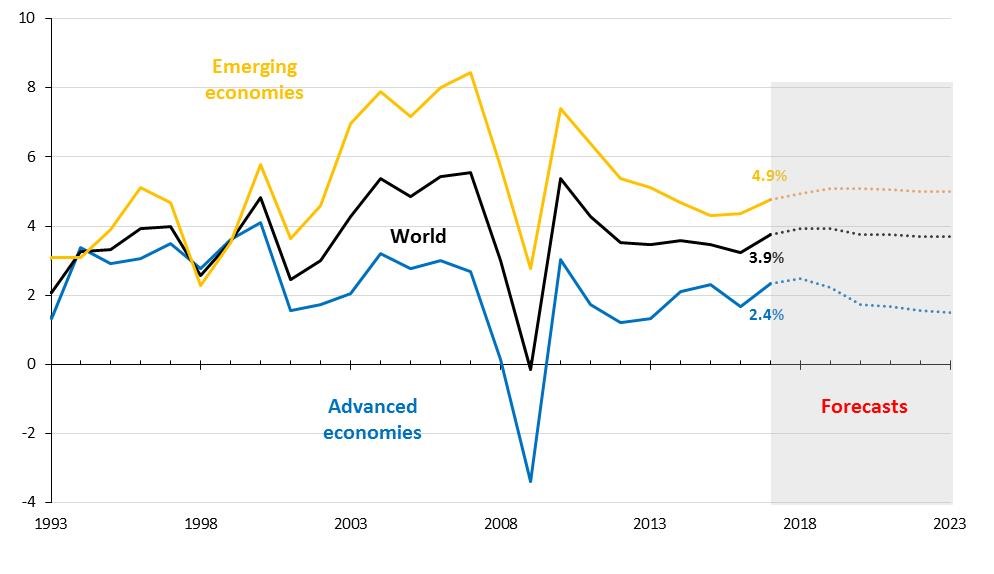

A decade after the eruption of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the world economy has finally returned to a more sustained pace of expansion (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: World GDP annual growth (in %, constant prices). Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, April 2018 and July 2018 update

Yet major challenges still remain, as the engines of long-run growth have still not recouped their pre-crisis power. The subdued growth in productivity in advanced and emerging countries alike, the slow recovery in investment and the persistently low income elasticity of international trade are all casting a long shadow over growth in the medium and longer term, calling for a deeper investigation of their root causes and of the possible policy remedies. However, disentangling the cyclical factors from the structural ones, in order to engineer the most appropriate policy responses is proving to be a difficult task. The first section of this book aim to shed some light on the structural and cyclical factors at play behind the slowdown in the supply-side drivers of economic growth, by revisiting the debate on the secular stagnation hypothesis (P. Pagano and M. Sbracia); the slowdown in productivity growth in emerging market economies (E. Di Stefano and D. Marconi; I. Kataryniuk and J. M. Martinez-Martin) as well as the debate over rising income and wealth inequality, especially in advanced economies (R. Cristadoro).

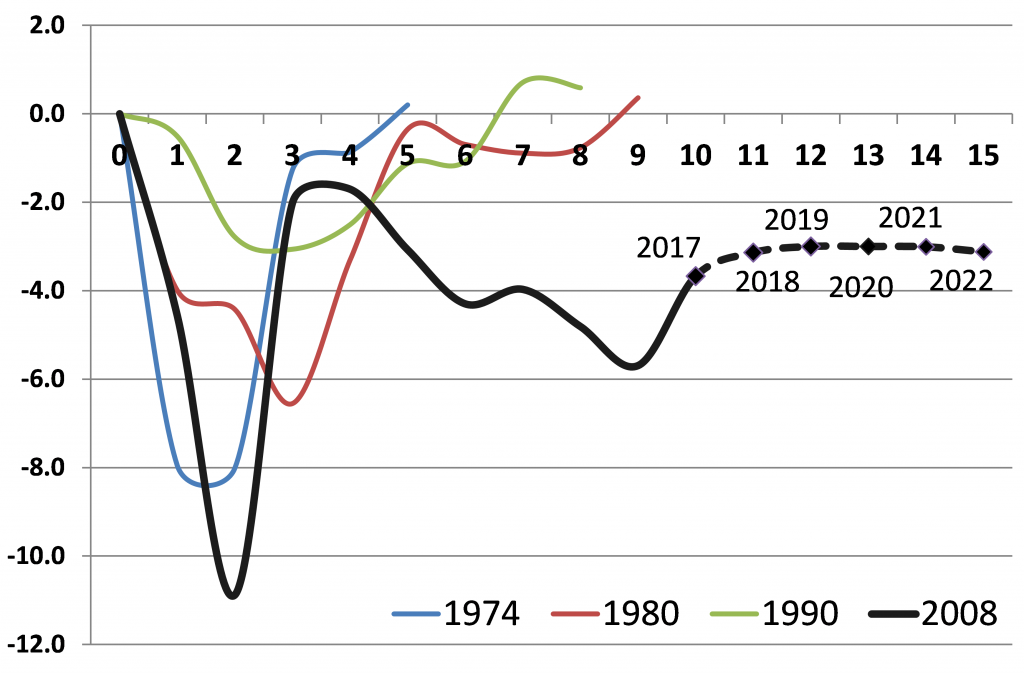

The second section of this book is devoted to the analysis of the components of aggregate demand in the wake of the GFC. A. Borin, V. Di Nino, M. Mancini and M. Sbracia investigate the causes of the sluggish recovery in global trade volumes and the fall in the income elasticity of trade. They show that the income elasticity of trade is highly cyclical, rising above unity during periods of above-trend GDP expansion and falling back to around unity in the long-run. As a consequence, one would expect income elasticity to recover as economic activity, and especially investment, goes back to their long-run trend, returning towards one and only exceeding this value if GDP and investment growth remain persistently above trend. In the years preceding the GFC, above-trend growth in aggregate demand, and particularly in consumption in the United States, was fueled by the expansion of debt. However, excessive indebtedness eventually resulted in the sub-prime crisis which triggered the GFC (V. Grossman-Wirth and C. Marsilli). Alongside trade, and strictly connected to it, business fixed investment remained depressed worldwide, particularly in major advanced economies, for a prolonged period of time after the crisis, only showing initial signs of recovery in recent months (see Fig. 2 below). The analysis conducted by I. Buono and S. Formai shows that the GFC has brought about a structural change in the determinants of investment demand, with financial uncertainty affecting the speed of recovery in fixed capital formation to a greater extent than previously. Moreover, in some countries, most notably the peripheral European countries, business investment has become more sensitive to changes in borrowing costs in recent years.

Figure 2: World gross fixed investment annual growth gaps during and after recessions. Source: IMF data, computations by the authors

In the wake of the GFC, central banking – and, in particular, monetary policy management – in advanced economies went through deep transformations, entering unchartered waters, as highlighted in the third section of the book. After the collapse of Lehman Brothers, central banks in major advanced economies adopted a number of extraordinary measures to support liquidity and lowered official interest rates to near zero in early 2009. At the same time, they also began implementing so-called unconventional policy measures with the aim of restoring the monetary transmission mechanism, improving access to finance and supporting the sluggish recovery. Fiscal consolidation efforts initiated in 2010 left monetary policy as the “only game in town”.

The persistence of low inflation rates in spite of the highly accommodative monetary policy stance represents a major challenge for central banks in the main advanced economies. The chapter by Berganza, F. Borrallo, and P. del Río shows that the persistence of inflation and the increased importance of backward-looking inflation expectations in some countries may pose risks for inflation-expectation anchoring and central bank credibility.

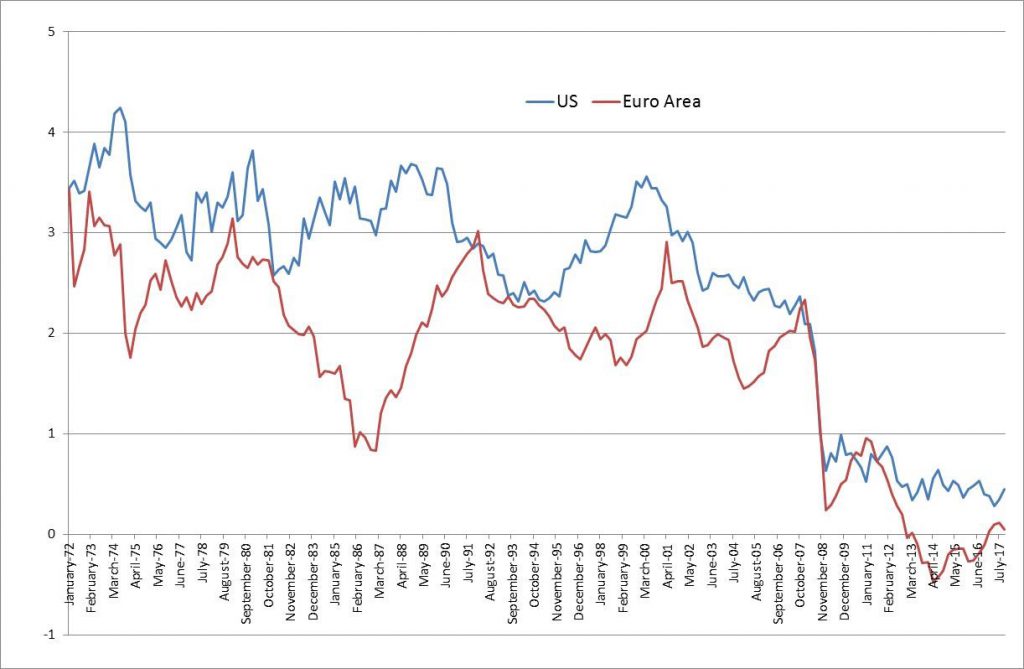

There is ample evidence that real interest rates have progressively declined since the 1980s in most advanced and emerging economies, and currently stand at very low levels (Figure 3). The persistence of this trend, as well as its intensification during the GFC, calls for a deeper investigation on their driving factors as well as on their potential implications, both for the conduct of monetary policy and for financial stability. In this context, I. Hernando, D. Santabárbara and J. Vallés argue that the normalization of monetary policies, the change in the growth model of some emerging countries and the socio-demographic and productivity trends would point to a gradual recovery in real interest rates, over a medium-term horizon, albeit with a high degree of uncertainty, both as regards the magnitude of the rise and its timing. Over the longer term, this trend may tail off in a context of limited technological progress, which fails to boost investment, or if investment growth in the emerging economies declines more sharply than expected.

Figure 3: Natural interest rates in the U.S and the euro area (in %). Source: Holston, Laubach and Williams, 2016.

Another feature of the global economic landscape in the last few years is the substantial increase in uncertainty, with significant implications for the conduct of macroeconomic policies. These uncertainty shocks stem mainly from developments in financial systems in some parts of the world and from political and economic policy outcomes. L. Ferrara, S. Lhuissier and F. Tripier present and discuss several measures of uncertainty that have been put forward in the literature, now widely used in empirical analyses, and describe the theoretical channels of transmission of uncertainty on macroeconomic activity and financial markets. Implications of higher uncertainty for the conduct of macroeconomic policies are of major importance.

In section 4, we come back on major disruptions in countries’ external sectors generated by the GFC. The large drop in global trade, slump in economic activity and turmoil on financial markets, as well as the subsequent economic policy reactions, all generated large movements in external variables such as capital flows and exchange rates.

We observed wide fluctuations in portfolio flows, banking flows and foreign direct investments before, during and after the GFC. M. Bussière, J. Schmidt and N. Valla show evidence of some stylized facts in international financial flows around the GFC, based on an empirical analysis of a large set of advanced and emerging countries. What are the drivers of those movements in capital flows? There have been some tentative explanations, especially regarding the collapse in banking flows. Among the possible drivers, the role of risk aversion and the high level of uncertainty have been put forward, but the correction from a pre-crisis global banking glut, the intensification of the disintermediation process or the impact of the trade collapse on trade credits are also convincing arguments. Against this backdrop, it is crucial to understand to what extent unconventional monetary policies have sustained capital flows. A. Ciarlone and A. Colabella look at the effects of the ECB’s asset purchase programs (APPs) on the financial markets of a set of central, eastern and south-eastern European (CESEE) countries. They show that the implementation of the APPs helped to support cross-border portfolio investment flows to, and larger foreign bank claims on, mainly through a portfolio rebalancing and a banking liquidity transmission channel.

Finally, as argued in the open economy literature, there is a close relationship between exchange rates, capital flows and monetary policy. S. Haincourt shows that a currency appreciation driven by a fall in risk premia is likely to have less adverse effects on GDP and inflation than one driven by a monetary policy shock. In addition, comparing the United States and the euro area, model-based results show that the euro area is more sensitive to a currency appreciation, most likely because of its higher degree of openness.

This post written by Laurent Ferrara.

It’s a U.S.-centric world. The U.S. has been the main engine of growth pulling the rest of the world economies.

Unfortunately, the small and slow tax cuts, Dodd-Frank dampening lending, Obamacare reducing discretionary income, piling-on many more regulations in many industries, depressing optimism, like “you didn’t build that,” etc. resulted in a very expensive and weak recovery.

Your attack on Dodd-Frank is beyond stooopid but then you led with this nonsense:

“It’s a U.S.-centric world. The U.S. has been the main engine of growth pulling the rest of the world economies.”

Can you say China? Peaky outdoes his normal incoherence in spades!

depressing optimism, like “you didn’t build that,”

peak, your innuendo about this quote indicates either you are ignorant of what obama was saying, or you are intentionally misleading what he was saying. which is it? perhaps as evidence, why don’t you come out and interpret exactly what obama was discussing in this quote? try to be honest for once in your life peak.

U.S. GDP growth would’ve been even worse without the much smaller trade deficits, the fracking boom, and Fed quantitative easings.

“smaller trade deficits”?

Oh my – this unsupported rant will get you fired by Wilbur Ross. Be careful there.

Once again we need to direct Peaky to http://www.bea.gov

Table 1.1.5. Gross Domestic Product

Net exports of goods and services went from negative $520.6 billion in 2016 to $578.4 billion in 2017.

But Peaky claims that a smaller trade deficit helped GDP growth? He not only gets cause and effect backwards again – he has no clue what the facts were as usual.

I think we can say Central Banks can reduce inflation easily but cannot do the opposite very well if at all

PT,

you obviously do not understand banks.

If you read Roggoff and Rheinhart you will find recoveries from recessions/depressions where the financial sector is one of the main causes is always weak.

Why so. Banks increase their standards for lending so there are no bad debts period.

Add to that a housing bubble that was pricked and thus the main transmission channel for lower interest rates is somewhat morbid.

The lack of business confidence has been shown to be a crock as an excuse also

Not Trampis, what economic recovery in U.S. history was weaker than the Obama recovery? Even after the downturn in the ‘30s bottomed, there was strong cyclical growth, although monetary policy made it worse, since we were on the gold standard and fiscal policy was new and weak. The 1990-91 recession had the S&L crisis. Yet, Bush “no new taxes” had a stronger recovery and the economy was booming eight years later. I could go on.

The Obama recovery was persistently weak, even after enormous stimulus spending and quantitative easings, along with TARP. And, as I stated above, Dodd-Frank restricted lending – it went from one extreme before the crisis to the other after the crisis. Moreover, you seem to believe higher taxes and more regulations on businesses don’t matter. You obviously don’t understand anything.

We have covered this before – it was weak because the Republicans undermined fiscal stimulus in part by listening to nitwits like you who would squander stimulus with tax cuts for the rich. No Peaky – you understand nothing except incessant right wing babbling.

Mate ( an endearing aussie term) ,

Banks react to a financial crisis by radically lifting their lending standards,

I remember reading Calculated Risk and he and Tanta were highlighting this.

Banks are very scared of losing money via bad debts because they were lax before the crisis and they go to the other extreme afterwards.

Thus after this you must use fiscal policy. Unfortunately like us downunder you had no shovel ready infrastructure projects ready to go

As I said R& R outline this very well.

“PT, you obviously do not understand banks.”

He clearly does not. Which is why he is known as a failed banker!

Much more than the financial crisis is causing persistently weak growth. I’ve explained some of it before, including inadequate tax cuts, too much regulation, excessive entitlement spending, extended unemployment benefits, slower optimism. Moreover, I cited Krugman that firms, e.g. Apple, aren’t investing much in productive capacity and hoarding cash. The failure of a stronger cyclical recovery resulted in much higher debt to GDP.

You’ve cited Krugman? My Lord – what he writes clearly undermines your right wing babble.

“Apple, aren’t investing much in productive capacity and hoarding cash.”

Lord – your stupidity burns. Of course Apple does not invest in factories. They outsource production to Foxconn. And hoarding is just a polite way of saying tax evasion. C’mon Peaky – even the dumbest person on the planet knows this. But not you?

Prof Chinn,

I am having Kansas and Wisconsin withdrawal symptoms. Even a bit of Oklahoma would help. Please post!!!

The chapter topics sound interesting and I’m sure it’s a handsome book. Unfortunately, it comes at an equally handsome price. It’s bad enough that much of modern economics is specialized and intellectually inaccessible to the proverbial “Swabian housewife”, but the price of books makes that problem even worse. It’s no wonder that too many people end up getting their economic news from cable talk shows.

Europe is largely a Socialist structure and in the past decade the development is largely debt-funded due to many institutional designs. If the US and Europe could score a deal, I take it as a big supply-side plus. Though I think a meaningful deal may take at least years of negotiation (before it’s usurped).

“Europe is largely a Socialist structure”

OMG. Try to accep that the last socialistic countries died in Europe in1989. A good first step is to understand the difference between social democrates and socialists, social democratic policies are quite popular in Europe and deliver quite good results.

rarely do we agree. but i find it fascinating how the conservative describes a democracy that votes differently than his as socialist, rather than voter choice. a democracy need not vote conservative to be considered a democracy!

The most socialist countries in the world are mostly in Western Europe. They have high unemployment and underemployment, high taxes, and much lower per capita incomes, than the U.S..

They live in much smaller houses, drive much smaller cars, or ride bicycles, and have fewer shopping malls per capita. They lag the U.S. in the Information and Biotech Revolutions by a huge margin.

They have generous welfare programs and more government jobs. A strong safety net is very comfortable. Some people want or got use to a cradle to grave government to take care of them.

A better system is one that includes promoting work, higher incomes, individual responsibility, and a short or temporary, but larger safety net. We had some restructuring of the economy in the Obama years, and it wasn’t good.

“individual responsibility” would be nice if certain failed bankers were more responsible for their actions.

Bankers were very successful implementing the government’s giant social program.