Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Enrique Martínez-García (Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas), based on his forthcoming article in Studies in Nonlinear Dynamics and Econometrics. The views expressed here are those solely of the author and do not reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

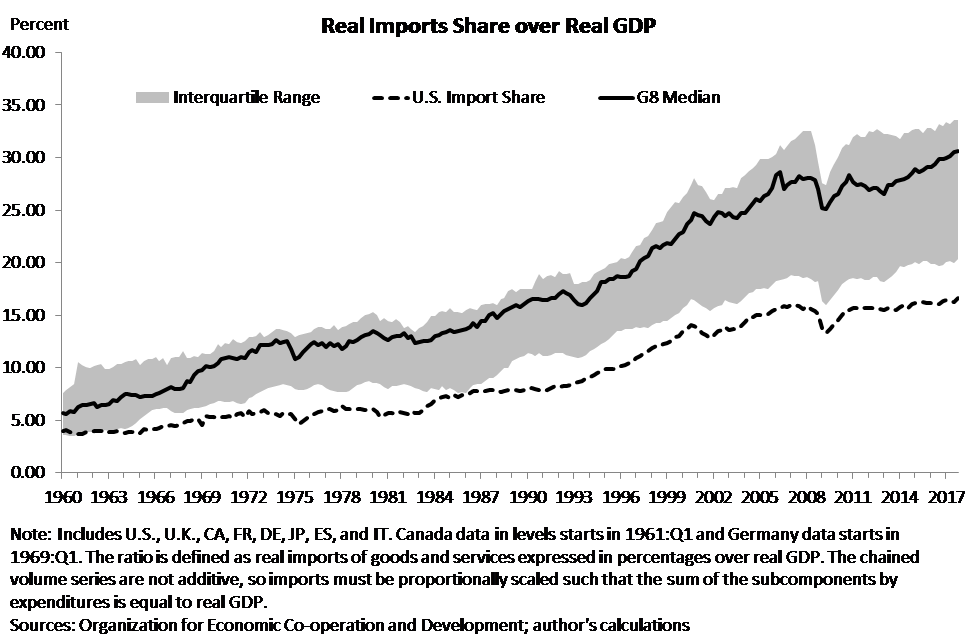

A sustained wave of globalization has led to deeper ties in the post-World War II period: The decision to terminate the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold in 1971 effectively ended Bretton Woods, ushering in a new era of fiat and free-floating currencies. The international monetary system has evolved since—removing the multilateral constraints of Bretton Woods (which fixed exchange rates and distorted the allocation of resources with capital controls). Current account and subsequently capital account liberalization followed, deepening trade relations as moving goods across borders became increasingly cheaper and trade barriers declined (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ties that Bind: Deepening Trade Linkages

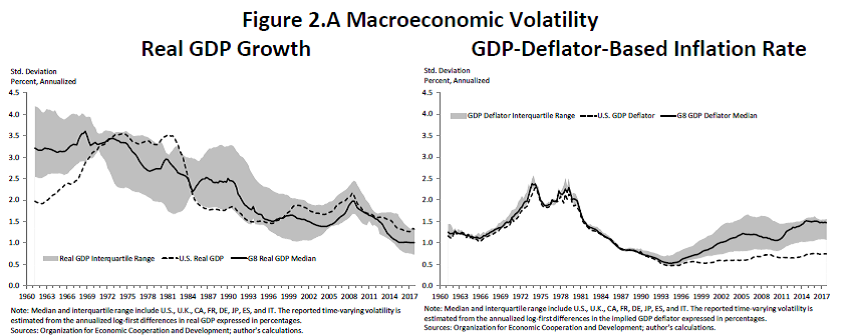

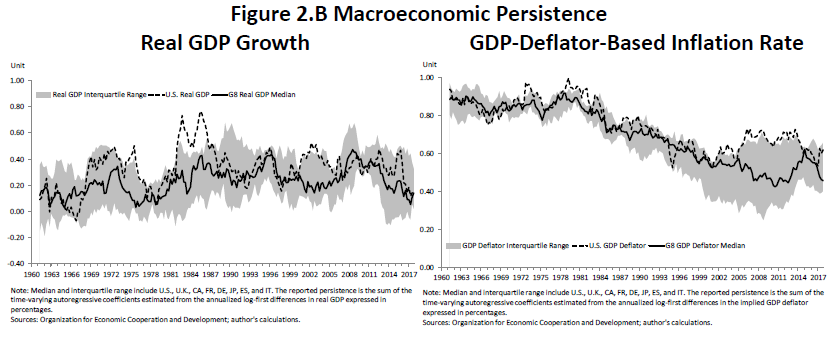

Business cycles across the eight largest advanced economies have notably changed since the 1960s: After the Great Inflation period of the 1970s, major advanced economies (U.S., U.K., Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Japan, and Canada which I collectively refer to as the G8) experienced declining inflation rates and somewhat more robust growth until the mid-2000s. Since the 2008 global recession, these major advanced economies have experienced softer growth and a prolonged episode of low inflation. In Martínez-García (2018), I document a period of declining macro volatility since at least the 1980s (in what became known as the Great Moderation period), followed by increasing and diverging inflation volatility patterns since the mid-1990s (Figure 2.A). The evidence also suggests significant shifts in inflation persistence (Figure 2.B).

Figure 2.A Macroeconomic Volatility

Figure 2.B Macroeconomic Persistence

The main shifts in business cycles observed across major advanced economies can be summarized as:

- Changes in macroeconomic volatility (Figure 2.A):

- Gradual yet sizeable declines in real GDP growth volatility since the mid-1970s, predating the onset of the Great Moderation in the 1980s. Contractions became both shorter and less frequent during the Great Moderation, as growth volatility declined.

- Widespread declines in inflation volatility during the 1980s and early-1990s, after experiencing high volatility in the 1970s accentuated during the oil crises of 1973 and 1979. Rising inflation volatility—mostly concentrated among European countries—and greater cross-country disparities have followed since the mid-1990s. Interestingly, this coincided with tighter monetary arrangements at the regional level—the three stages for the implementation of the Economic and Monetary Union among European Union countries started to roll over in July 1990 (Koech and Martínez-García (2011)).

- Forecastability of either real GDP growth or inflation with simple univariate time series models tends to improve whenever macroeconomic volatility is lower (see more on the forecastability of inflation in Duncan and Martínez-García (2015), Kabukçuoglu and Martínez-García (2018)).

- Changes in macroeconomic persistence (Figure 2.B):

- The persistence of real GDP growth has remained low and fairly stable over time.

- The persistence of inflation was quite high earlier on, but has gradually declined since the late-1970s (leveling off around the time of the 2008 global recession).

- Other features of the business cycle have changed as well (see Martínez-García (2018) for more details):

- The synchronization of real GDP growth across countries remained low and largely stable until it quickly spiked in the aftermath of the 2008 global recession.

- Before the mid-1990s, the cross-country correlation (synchronization) of inflation was very high and countercyclical. Since then, the cross-country correlation has declined (only gaining some ground after 2008) and inflation has become largely acyclical.

A large body of research has tried to identify the role played by different factors—including structural transformation explanations—in changing business cycles: The literature continues to debate whether the observed business cycle changes—the Great Moderation in particular—are the result of “good luck,” improved macroeconomic policies (particularly better monetary policy), changes in the structure of the economy or structural transformation, or some combination of all of them (see, e.g., Clarida et al. (2000), Stock and Watson (2003), Galí and Gambetti (2009), Benati and Surico (2009), among others).

Financial globalization (through deepening domestic and international financial markets, increased international capital flows, financial deregulation, etc.) unfolding since at least the 1970s is one of the structural transformation explanations advocated by Cecchetti et al. (2005) and Dynan et al. (2006), among others. Globalization through trade (increased international trade openness) also features as another prominent structural transformation explanation in the work of Cecchetti et al. (2005)> and Bianchi and Civelli (2015), among others. Martínez-García (2018) continues this line of inquiry specifically looking at the impact of trade linkages on cross-country business cycles.

Consistent with standard theory, there is a robust empirical relationship between conventional measures of trade openness and the evolving business cycles: Arguments based on structural transformation postulate that changes in institutions, new technologies, or even globalization can affect the economy’s ability to absorb shocks and alter the propagation of different shocks over the business cycle. The workhorse open-economy New Keynesian model suggests that those shifts can be partly attributed to (nonlinear) changes in deep structural parameters—and, in particular, to deepening trade integration (an important dimension of globalization)—as shown in Martínez-García and Wynne (2010) and, more recently, in the analytical exploration of that framework found in Martínez-García (2017).

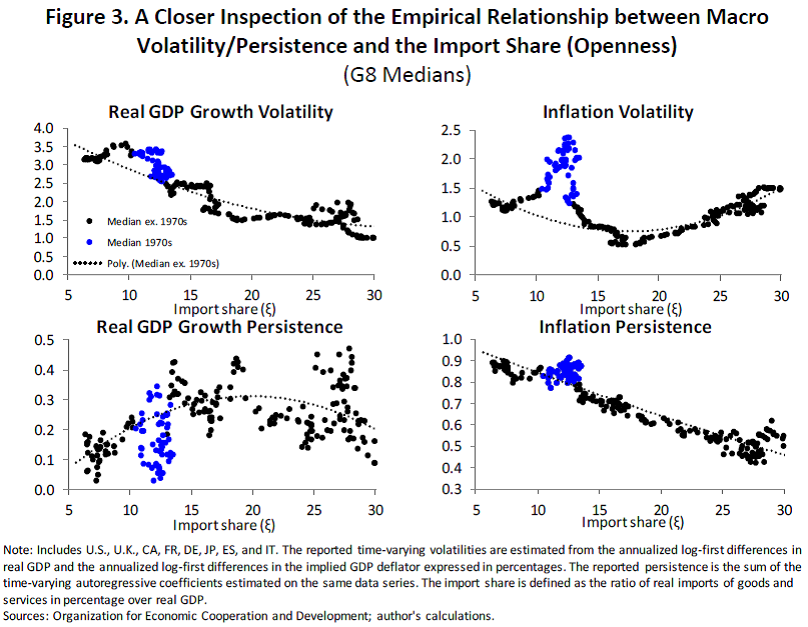

Motivated by the implications of the workhorse open-economy New Keynesian model, I explore a flexible yet nonlinear specification to capture the empirical relationship between greater trade openness and the reported central tendency patterns of shifting business cycles across the major advanced economies. The illustration in Figure 3 (a highlight of the findings in Martínez-García (2018)) shows that trade openness indeed has a strong albeit nonlinear association with key observed business cycle features—broadly consistent with the implications of the workhorse open-economy New Keynesian model.

Figure 3. A Closer Inspection of the Empirical Relationship between Macro Volatility/Persistence and the Import Share (Openness)

These findings have implications for our understanding of business cycles and for monetary policy: The ongoing wave of global economic integration is a transformative phenomenon that has shaped the world economy for decades and may continue to do so for many decades to come. Globalization through trade has not negated the central banks’ ability to influence domestic economic conditions and achieve their macroeconomic stabilization goals (a point forcefully argued by Woodford (2010)). However, what theory (Martínez-García (2017)) and evidence (Martínez-García (2018)) suggest is that globalization can impact the economic environment in which policymakers must conduct policy:

- On the international monetary transmission mechanism (making domestic policy outcomes more dependent on the actions of foreign policymakers).

- On the trade-off between inflation and real economic activity confronted by policymakers (the slope of the open-economy Phillips curve (Borio (2017)), but also that of the open-economy dynamic Investment-Savings (IS) equation).

- On the attainable policy frontier on macroeconomic volatility (the policy trade-off between real GDP growth volatility and inflation volatility also known as the Taylor curve (Bernanke (2004))).

Furthermore, according to theory, globalization’s contribution crucially depends on more than the degree of openness of the economy—the always contentious trade elasticity, changes in labor market institutions, the interplay between monetary policy and fiscal policy, etc., must be considered as well. Hence, scholars and policymakers must continue to further our understanding of the effects of globalization in general and on the conduct and international transmission of monetary policy in particular.

This post written by Enrique Martínez-García.

I’m not certain the over-arching argument being made here. That the openness of different state (nation) economies and freeness of capital flows lowers the rate of inflation while at the same time lowering growth rates, and the slower these two things become, the easier it gets to predict the economy??

I don’t mean to offend when I say I don’t see any new real deep insights here, or “revelations”. And if wages are lower compared to that “lower rate of inflation” or there is high unemployment for a significant portion of the population, it probably doesn’t feel like “low inflation” to these people.

Dear Folks,

It looks like it is growth in the import share of goods, not services, that is being captured in Figure 3. Can this be checked?

Julian