Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Emine Boz (IMF), Nan Li (IMF) and Hongrui Zhang (IDB). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, IDB, their Executive Boards, or the managements of those organizations.

Some major economies specializing in sectors that face relatively high trade costs, such as services, tend to run current account deficits, whereas countries specializing in more easily tradable sectors, such as manufacturing, often run surpluses. This column tests this casual observation using a dataset comprehensive across time and countries, and finds a negative impact of effective exporting costs on the current account, but the average effect is quantitatively limited. It thus follows that the contribution of trade costs to observed global imbalances has been modest.

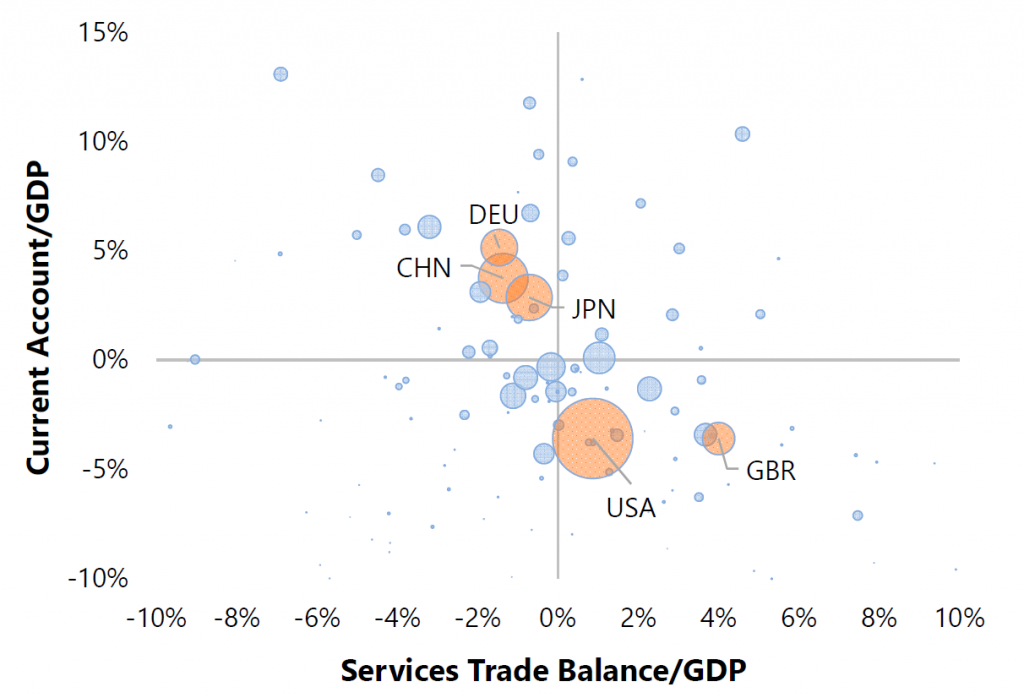

The height of trade costs, and its potential impact on countries’ external balances, have recently gained popularity in discussions in policy and academic circles. An important observation in these discussions is that some major economies that specialize in sectors facing relatively high trade costs, such as services, tend to run current account (CA) deficits while countries specializing in sectors characterized by low trade costs tend to run CA surpluses. For example, Figure 1 illustrates the negative correlation between services trade and CA balances where both are measured as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) for the world’s five largest economies.

In our recent work, entitled “Effective Trade Costs and the Current Account: An Empirical Analysis”, we test the hypothesis that trade costs, especially as they apply to countries’ prime export sectors, can have an economically significant impact on CA outcomes. If this hypothesis is correct, it can have far-reaching policy implications. For example, global imbalances could shrink if trade costs became more closely aligned across sectors through either lower trade costs for services or higher costs for manufacturing. We thus study a globally representative sample of countries over nearly half a century and empirically quantify the effects of trade costs on CA outcomes while accounting for specialization patterns.

We measure disaggregate trade costs by applying the Ricardian trade model of Eaton and Kortum (2002) to data on bilateral trade flows in agriculture, manufacturing, and services. Deriving separate estimates for different years and sectors, we allow the trade costs and their relationship with trade flows to vary over time and across sectors. Importantly, our measures of trade cost include nontariff barriers that are difficult to quantify but potentially pervasive, especially in the services sector. Another important feature of our bilateral trade cost estimates is that they are asymmetric between importers and exporters because we allow them to have an importer-specific component, which is intended to capture importing barriers that apply to all trading partners in a nondiscriminatory fashion. Barriers such as regulatory, licensing or reporting requirements, the quality of institutions and the rule of law are prime examples of such nondiscriminatory obstacles to trade.

Comparative advantage is difficult to measure because it requires characterizing the differences between world prices and domestic prices that would have prevailed under autarky. Since the counterfactual relative prices cannot be observed, we follow Hanson, Lind, and Muendler (2018) and use the gravity equation to infer each country’s sectoral export capability before applying a “double normalization” to obtain the comparative advantage. In this procedure, the first normalization is relative to the world average of export capability and yields the absolute advantage for each country-sector pair. Second, we normalize absolute advantage relative to its countrywide average across sectors to remove the potentially confounding effects of domestic aggregate growth. The resulting measure of comparative advantage reflects differences in countries’ technology adjusted for input costs and is more refined than the traditional “revealed” comparative advantage of Balassa (1965), which is calculated using only observed gross trade flows.

Armed with these estimates, we compute aggregate effective trade costs to capture the size of overall costs to countries’ natural exports and natural imports. First, we take the disaggregated bilateral trade costs at the sector level and aggregate across trading partners (using either lagged trade weights or free-trade weights), generating two separate measures at the country-sector level: costs to import and costs to export. Next, we aggregate across sectors using sectoral comparative advantage as weights and arrive at effective trade costs at the country level.

Introducing the estimates of aggregate effective trade costs—separately for both the export and import sides—to an empirical model of CA determination developed by the IMF for the assessment of countries’ external balances, we find that countries facing higher export costs in their comparative advantage sectors have modestly lower CA balances.1

For the sample period of 1986 to 2009, a 10-percentage point unilateral reduction in aggregate effective export costs for an average country is associated with a CA balance improvement amounting to 0.5-0.8 percent of GDP (depending on the aggregation scheme). Estimates based on a 2001-2014 sample yield effects that are about half the size of those for the earlier period. Effective costs of importing generally have small and statistically insignificant effects. These average effects mask substantial heterogeneity across countries. For example, a nonnegligible portion of the current account deficit in the US can be attributed to higher-than-average effective costs to export.

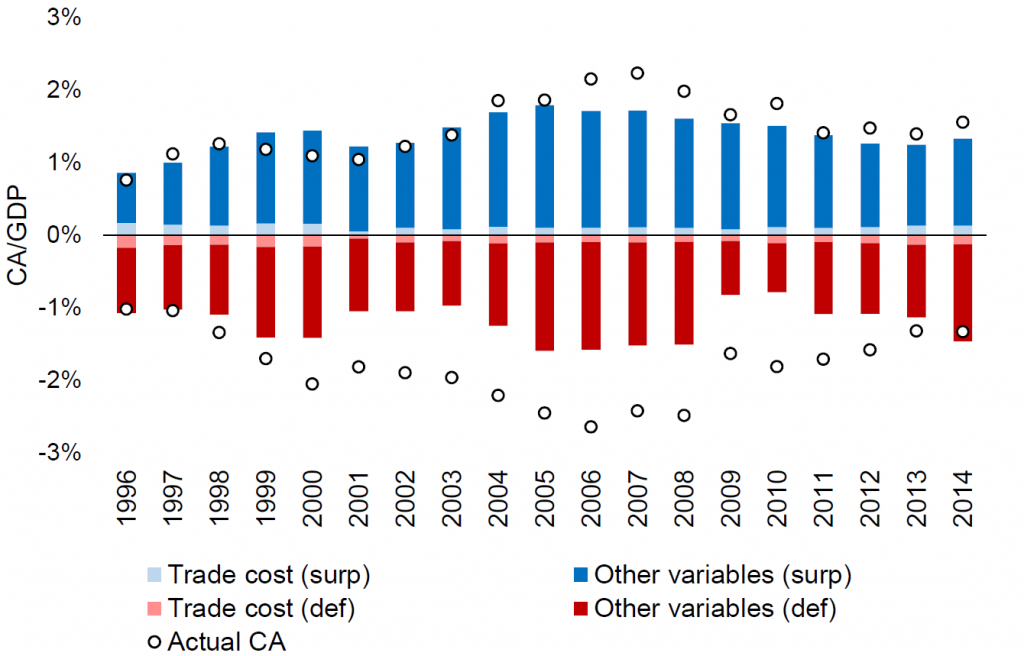

Consistent with the above estimates, Figure 2 suggests that the contribution of trade costs to global imbalances has been minor. After sorting countries into CA surplus and deficit groups, the actual and predicted values of the aggregate CA balance of each group are calculated as a share of their total GDP. The predicted values are then decomposed into those predicted by the trade cost measures, both when exporting and importing, and by other factors included in the CA model. Looked at in this way, the contribution of trade costs to global imbalances has been a small fraction of the actual imbalances throughout the sample.

Notes: This figure plots the actual values (open circles) and predicted values (bars) of the CA separately for surplus (blue) and deficit (red) countries. The predicted values consist of those derived from effective trade costs (light shading) and from other variables in the IMF’s latest current account model developed for External Balance Assessment (dark shading), documented in IMF (2018). Effective trade costs are calculated using lagged trade shares.

While our analysis remains agnostic regarding the underlying mechanisms at work, the literature is ample with theories that generate small effects of trade costs on current account balances. A number of studies have introduced mechanisms that link trade costs to the CA—where these effects depend on the extent to which the shocks tilt the expected future profile of intertemporal prices and income, central macroeconomic determinants of saving and investment. For example, in a seminal contribution, Obstfeld and Rogoff (2000) show that trade costs can lead to a wedge between the effective interest rates faced by the borrowers and creditors, thus may have a bearing on consumption and saving decisions. The CA effects of trade costs in that model, however, are unlikely to be significant, except at high levels of trade restriction. In more recent work, Barattieri, Cacciatore and Ghironi (2018), using data on antidumping investigations, find that protectionist policies can generate at best a small improvement in the trade balance, and highlight the contractionary effects of tariffs through inflationary pressure and misallocation of investment towards less efficient producers in a small open economy model.

References

- Barattieri, Alessandro, Matteo Cacciatore and Fabio Ghironi, 2018, “Protectionism and the Business Cycle,” NBER WP 24353.

- Boz, Emine, Nan Li, and Hongrui Zhang, 2018, “Effective Trade Costs and the Current Account: An Empirical Analysis”, IMF Working Paper No. 19/8.

- Chinn, Menzie D., and Eswar S. Prasad, 2003, “Medium-term Determinants of Current Accounts in Industrial and Developing Countries: an Empirical Exploration,” Journal of International Economics, vol 59(1), pp. 47-76.

- International Monetary Fund [IMF], 2018, “External Sector Report, Refinements to the External Balance Assessment Methodology– Technical Supplement.”

- Eaton, Jonathan and Samuel Kortum, 2002, “Technology, Geography and Trade,” Econometrica, vol. 70, pp. 1741-79.

- Hanson, Gordon, Nelson Lind and Marc-Andreas Muendler, 2018, “The Dynamics of Comparative Advantage,” NBER Working Paper 21753.

- Johnson, Robert and Guillermo Noguera, 2017, “A Portrait of Trade in Value-Added over Four Decades,” Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 99, pp. 896-911.

- Lee, J., G. Milesi-Ferretti, J. D. Ostry, A. Prati, and L. A. Ricci, 2008, “Exchange Rate Assessments: CGER Methodologies,” IMF Occasional Paper No. 261.

- Obstfeld, Maurice and Kenneth Rogoff, 2000, “The Six Major Puzzles in International Macroeconomics: Is There a Common Cause?,” NBER Macroeconomics Annual, vol. 15, pp. 339-90.

- Phillips, Steven T., Luis Catao, Luca A. Ricci, Rudolfs Bems, Mitali Das, Julian Di Giovanni, Filiz D. Unsal, Marola Castillo, Jungjin Lee, Jair Rodriguez and Mauricio Vargas, 2013, “The External Balance Assessment (EBA) Methodology,” Working Paper No. 13/272, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

- Timmer, Marcel P., Erik Dietzenbacher, Bart Los, Robert Stehrer and Gaaitzen J. de Vries, 2015, “An Illustrated User Guide to the World Input-Output Database: The Case of Global Automotive Production,” Review of International Economics, 23/3, pp. 575-605.

[1] The CA model is documented in IMF (2018) which builds on earlier work by Phillips et al. (2013), Chinn and Prasad (2003), Lee et al. (2008), among others.

This post written by Emine Boz, Nan Li, and Hongrui Zhang.

I’m not challenging the authors’ results, just making an observation. To me the results seem pretty counterintuitive, at least to my way of thinking. But then, some of the best research is counterintuitive, or why do it?? The whole point of research is to find things that don’t seem obvious on the face of it. I’m not 100% sold yet, but at first glance seems like a good paper on a very worthy topic. Something “dear leader” donald trump could learn from. After all, when you’re starting off from Camp Base Zero you can probably learn something reading a bubble gum wrapper.

I’ll try to find time/room to fit reading the paper inside this week and giving a better comment later, but I have the foreboding and gloomy feeling some of the math is going to escape me. We’ll give it a whirl anyway.

I’m going to do something I’m extremely reticent to do. That is give a certain politician credit for something. I have a strong feeling I am going to have extreme regret about this later, probably to the point of near self-mutilation. But I’m not going to listen to my gut, not going to listen to my very best instincts that tell me ONCE AGAIN this woman nearing senility is going to CAVE like a deep moon-crater and give WAY MORE than she should on donald trump’s wall (i.e. any funding higher than $0). Once again over the last roughly 16 years, I will run and try to kick the football as Nancy holds it out to make me fly into the air, and land on my back in the dirt, that I tried to believe that maybe instead of just winning a single battle, Nancy could just this once, just this once damned time win the WAR.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kd8XvjKXE9Y

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MmFfTJlIvhQ

What does clapping hands together have to do with the moving and passage of legislation, does anyone know?? It’s been 5 seconds since I typed this comment and I’m already having buyer’s remorse putting small faith in this senile weakling Nancy. Anyone have some bourbon I can steal??

There are certain parties on this blog, who have acted as if China’s IP theft is not a real issue. Maybe ironically, it’s my perception that the host of this blog isn’t one of them—i.e. he has discussed that ZTE should be punished and other issues, which I think reflects well on the blog host’s objectivity and neutrality on this issue. In other words, seeing things as they are and not cherry-picking. One doesn’t have to be a “China-hater” (although there are many in this sub-category) to feel the IP issue is troublesome, and a legitimate issue. Some people with strong affection to China may wish that China found other ways to excel—such as encouraging and rewarding Chinese citizens creativity and hustle. One only needs see the amazing success Chinese “implants” (please excuse the coldness of that word) in other nations to see no one is hurt more by Chinese government policies than Chinese citizens themselves.

I mentioned Deming’s Red Beads test in other threads before, and I often think of this in my mind when thinking of all the incredibly intelligent and resourceful Chinese I met in my time there, flustering away at jobs and tasks they are vastly over-qualified to spend a lifetime of doing. It may surprise many readers and the host of this blog how much hurt it puts in my heart in my more quiet moments to think of these highly intelligent Chinese people who are slaving away at jobs when they should be using their innate intellectual “gifts” and intellectual capital in much more life-affirming ways, but are not, because of a rotten system. Really, if not the same, nearly the same as it bothers me watching the “white American male” flounder over the last roughly 40 years with the death of manufacturing jobs. Play an imaginary violin here if you deem it appropriate….. or not. Be that as it may, the IP issue, whether you love China or illogically hate and despise it, is a real and legitimate issue.

https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2019-02-06/chinas-operation-cloudhopper-infiltrated-norwegian-software-firm

OK, kids!!! Who’s up for a Christmas vacation to Britain???

https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2019-02-07/pound-tumbles-after-boe-slashes-gdp-forecast-warns-rising-brexit-damage

Come on now, you know you wanna meet Keira Knightley.

Lots of interesting stuff on ZH today. Although not necessarily surprising (maybe they should get smart and join a credit union??)

https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2019-02-07/wells-fargo-online-banking-goes-down-customers-unable-access-accounts

The Supreme Court decision in McGrain V. Daugherty 1927 is something Trump’s lawyers may need to remind him of:

https://www.encyclopedia.com/law/legal-and-political-magazines/mcgrain-v-daugherty-1927

“The ruling clearly established Congress’ power to conduct investigations even without stating a specific legislative purpose. The decision dramatically expanded Congress’ ability to investigate the lives and activities of citizens. This power has been regularly exercised by Congress ever since. The decision was also considered the first to uphold the power of Congress or the courts to override on certain occasions claims of executive privilege if a president, his cabinet members, or presidential aides were called to testify.”

This inquiry was part of the Teapot Dome scandal, which paled in significance to the multiple of scandals involving Trump that Congress is rightfully investigating. What was that line in the SOTU?

https://www.cnbc.com/2019/02/06/trump-and-nixon-both-slammed-investigations-in-state-of-the-union.html

“If there is going to be peace and legislation, there cannot be war and investigation. It just doesn’t work that way!”

I love how this link immediately pivoted to this:

“Nixon, in his final State of the Union speech, called for an end to the Watergate investigation that ultimately led him to resign more than six months later.”

Even Watergate pails in comparison to the treason committed by Trump. Yea – the Usual Suspects here loved this unconstitutional blather from Trump. Which is OK as I bet this will be his last SOTU speech!

You need to address these problems directly (if you want to be non-lying, upright economist):

– are the trade prices artificially suppressed? what are the causes?

– what can you do in the US, and internationally?

I couldn’t really find an appropriate or topic related post to put this in, but feel it’s important, so I am putting this here.

https://www.scmp.com/business/banking-finance/article/2186017/china-launches-countrywide-bonds-health-check-default-wave