Today, we are fortunate to present a guest contribution written by Ashoka Mody, Charles and Marie Visiting Professor in International Economic Policy, Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University. Previously, he was Deputy Director in the International Monetary Fund’s Research and European Departments.

Hélène Rey, a professor at London Business School, argues that the U.S. Federal Reserve determines global monetary policy. The Fed determines the interest rate for the use of the world’s most dominant currency, the U.S. dollar. Fed policy decisions, therefore, trigger the “global financial cycle,” which causes global capital to slosh around the world, placing severe constraints on national monetary policies.

Some, however, insist that all central banks are equally effective (or ineffective). Claudio Borio of the Bank of International Settlements contends that central bank policies are powerless to move inflation rates. International competition keeps global inflation low, and central banks, in a misguided effort to prevent deflation, reduce interest rates to very low levels. Central banks thus encourage speculative investments, which eventually trigger financial crises. Raghuram Rajan, the University of Chicago economist, falls in this camp.

Others believe the opposite, tarring all central banks of unwarranted timidity after the onset of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Such critics claim that all central banks “failed even to lift inflation to their target” because they did not use their full stimulus capacity.

Rey is correct that the Fed is the world’s powerful central bank, but this is so not only for the reason she emphasizes. The Fed is also the world’s most credible central bank, which makes it hugely influential domestically and not just internationally. The Fed did raise the U.S. inflation rate to its 2 percent target. Early and aggressive Fed actions helped propel the U.S. economy to a quicker recovery; that same boldness prevented inflation expectations from falling. In contrast, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) and the European Central Bank (ECB), having allowed inflation rates to fall too low, proved unable to lift them back again.

Commentators do sometimes exclude the BOJ from equivalence with other central banks, presumably because it has failed, despite massive efforts, to pull inflation out of the doldrums. Many, most prominently Paul Krugman, have told the story of the BOJ’s past timidity, which caused investors and consumers to lose faith that the BOJ will continue its stimulative policies.

Expressing that perspective, Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic advisor of Allianz, recently described the Fed and the ECB as “the two most systemically important central banks.” But is the clubbing of the Fed and the ECB appropriate? In this essay, I document the costs of ECB timidity, which, I argue, arises from the political limits on its actions and which renders the ECB, by at least one metric, even less effective than the BOJ.

The ECB’s delay in quantitative easing

The ECB is intensely averse to inflation but is more tolerant of deflationary tendencies. This asymmetric predisposition is not the result of its mandate of achieving price stability. The ECB has chosen to interpret this mandate asymmetrically. It has focused on keeping inflation below 2 percent but has downplayed the goal of maintaining inflation close to 2 percent.

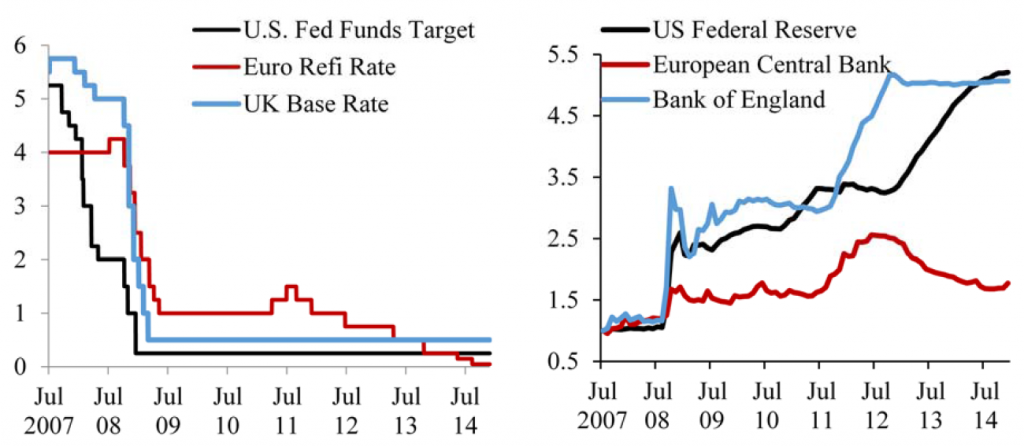

In periods of inflationary pressure, ideological commitment to “price stability” causes the ECB to maintain tight monetary policy. The ideology was manifest between 2001 and 2003. Although the pace of economic deceleration and inflation rates were similar on both sides of the Atlantic, the ECB lowered its interest rates only slowly and grudgingly while the Fed drastically cut rates. The ECB paid greater heed to inflation than to the economic slowdown. When national leaders badgered ECB president Wim Duisenberg to ease monetary policy, he famously responded, “I hear but I do not listen.” Similarly, after the start of the GFC, the ECB’s first action was to raise its interest rate in July 2008; more seriously, the ECB raised rates in April and July 2011, setting off financial panic and pushing the eurozone into prolonged recessionary conditions. In each of these cases, the ECB was fighting the threat of a phantom inflation, not recognizing that the ongoing economic slowdown would moderate inflation.

The ideological unity in raising the interest rate was such that even Mario Draghi, often viewed as more balanced than his zealous colleagues on the ECB’s Governing Council, publicly defended the rationale for the egregious July 2011 rate hike, both before and after the decision.

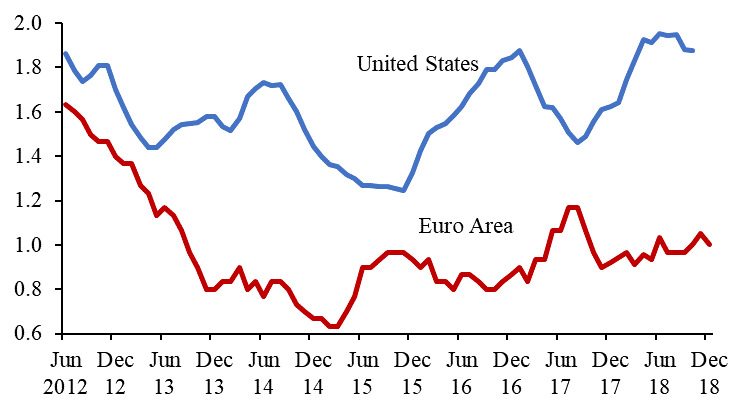

While ideology unified the Governing Council in the fight against inflation, divergence of national interests held it back in countering deflation. The divergent interests became evident towards the end of 2012. In the United States, where the inflation rate was much the same as in the eurozone, the Fed under Chairman Ben Bernanke stepped up bond purchases under its QE programs (Figure 1).

By thus helping to bring down long-term interest rates, the Fed sought to induce greater spending and thereby prevent a recession and deflation. In contrast, the ECB stood virtually still. The eurozone’s inflation rate began to fall steadily below the U.S. inflation rate (Figure 2).

(Three-month moving average of “core” annual inflation rates, percent). Sources: Eurostat: “HICP—All Items Excluding Energy and Food”; St. Louis Fed, FRED: “Personal Consumption Expenditures Excluding Food and Energy (Chain-Type Price Index).”

Note: December 2018 value for the Euro Area is an estimate.

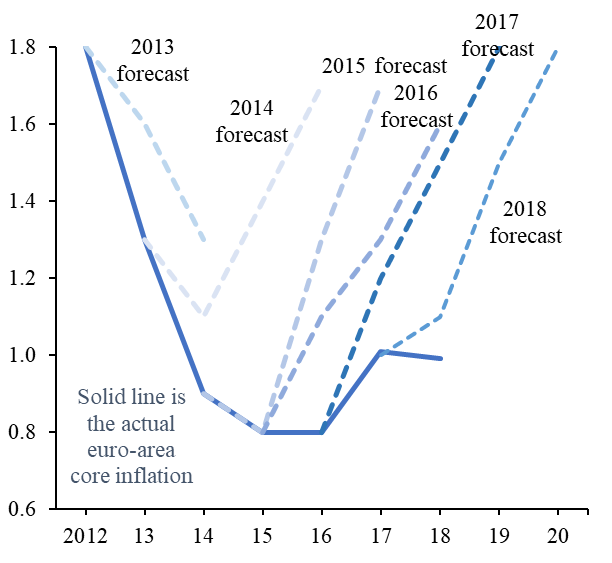

ECB leadership initially dismissed the decline in the eurozone inflation rate as temporary. In place of a major QE initiative, Draghi offered cheap talk. In November 2013, he said that the ECB had “a whole range of instruments,” which it would deploy “if needed.” In April 2014, he did acknowledge that ECB projections of a rise in inflation had proved incorrect “a few times.” He insisted, however, that the ECB would respond only if inflation remained low for “too prolonged” a period. Such deliberately vague phraseology was an unmistakable—and therefore unsuccessful—attempt to camouflage the tensions within the Governing Council. Northern member states, with Bundesbank president Jens Weidman in the lead, publicly opposed QE.

The consequences of delayed QE

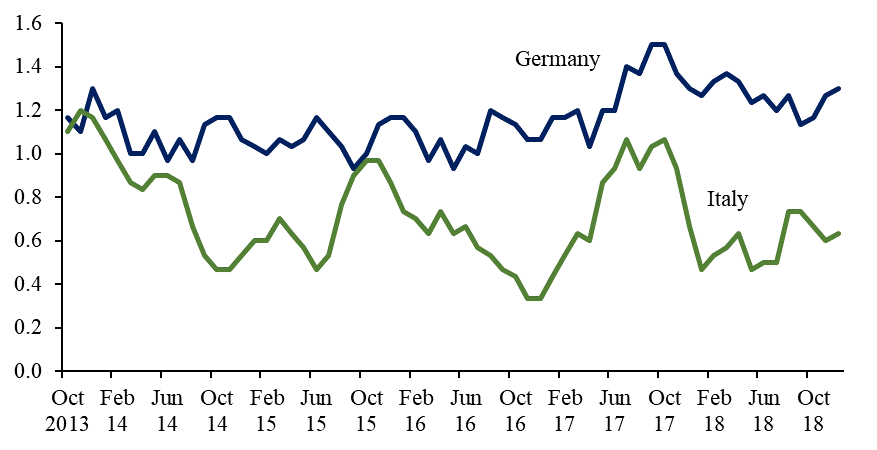

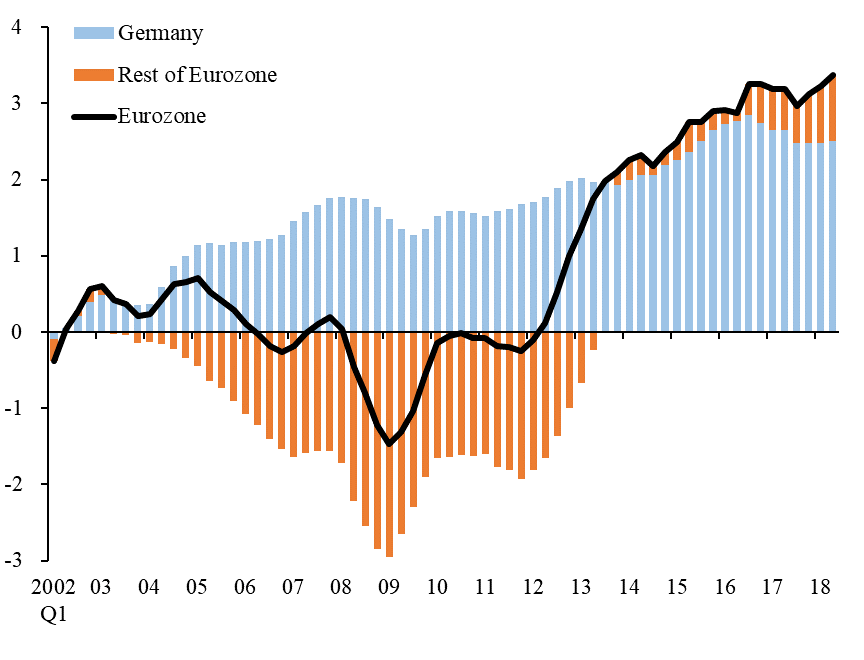

The ECB finally initiated QE in January 2015, but only after lowflation—persistently low inflation rates—had set in. But not only was the eurozone’s average inflation rate stuck at near 1 percent, a troubling divergence in inflation rates was manifest. The inflation rate in Germany was well above 1 percent, while in Italy it was well below 1 percent (Figure 3). This was predictable. Monetary policy was particularly tight for Italy, the weaker economy. That pushed the Italian inflation rate down, which kept the Italian real interest rate (the interest rate adjusted for inflation) much higher than Germany’s. Thus, tight monetary policy reinforced economic divergence within the eurozone.

The ECB continued to forecast that inflation would rise, but average inflation refused to budge (Figure 4).

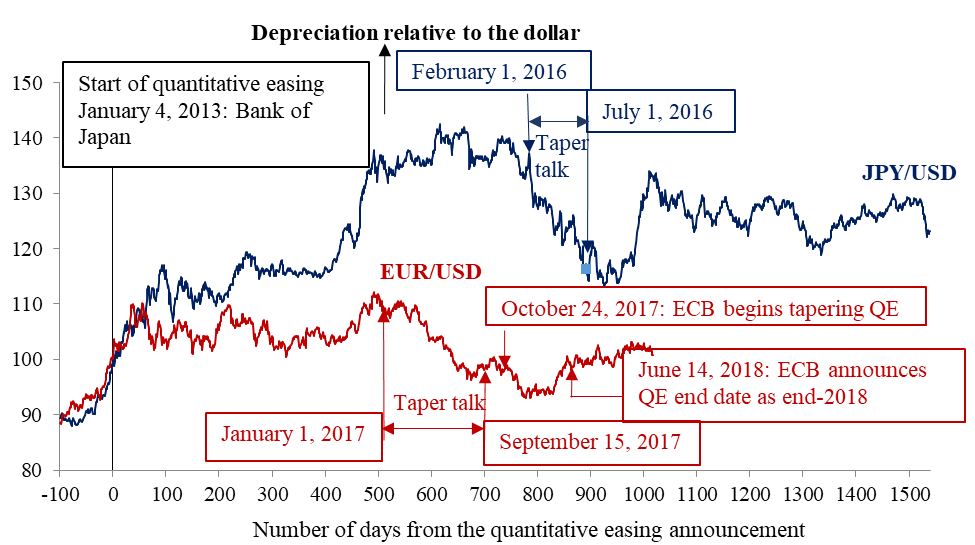

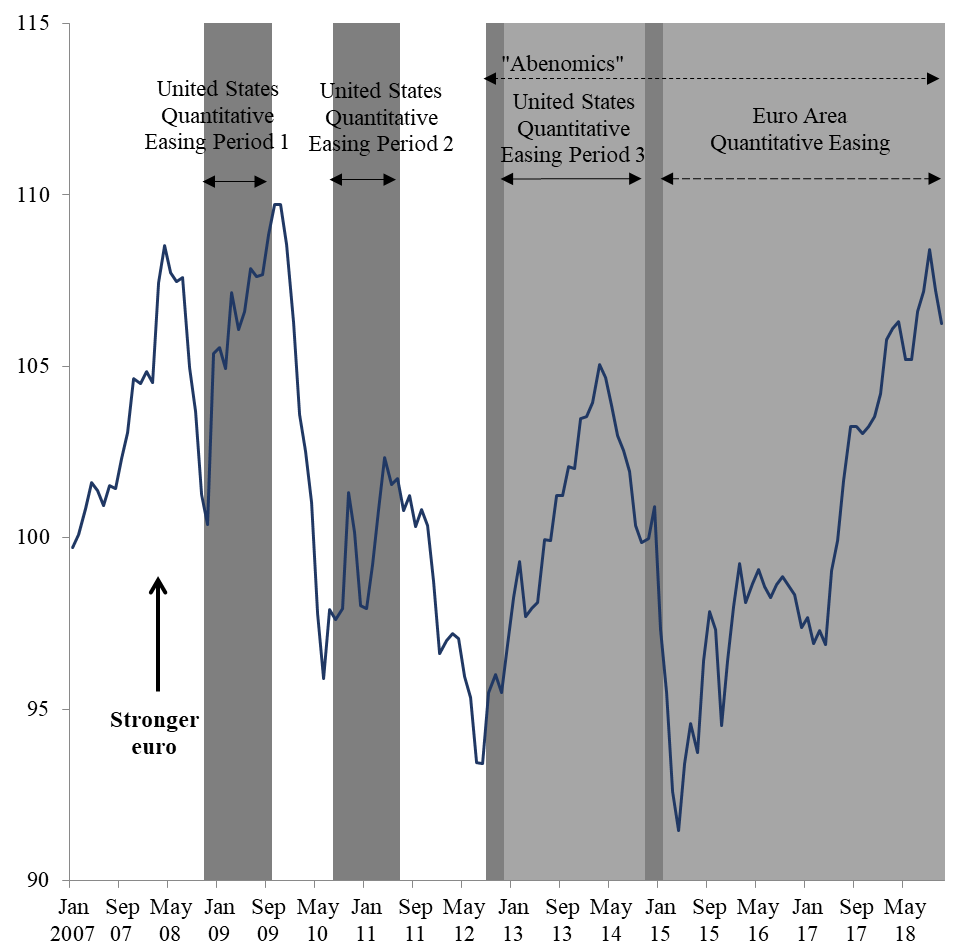

The ECB also remained unable to deliver a significantly weaker exchange rate to help boost growth and inflation. Normally, a QE-led decline in interest rates should cause the currency value to depreciate. Figure 5 aligns at time “0” the QEs initiated by the BOJ and the ECB. The yen depreciated substantially and remained weaker than at the BOJ’s QE starting point. The euro did depreciate in anticipation to the ECB’s QE, but at least some part of this was due to the Fed’s QE withdrawal in the final months of 2014. After the ECB began QE, the euro depreciated only briefly and then slowly reverted to its starting level. Thus, overall, the euro barely depreciated against the dollar.

The lack of euro depreciation against the dollar was due to the ECB’s threat as early as January 2017 that it planned to slow down its pace of bond purchases. In October 2017, Draghi delivered partially on that threat. He announced that, starting in January 2018, the ECB would halve its monthly purchases to 30 billion euros. Markets, therefore, had good reason to believe that the ECB would withdraw QE early, which kept the exchange rate buoyed in anticipation of the program’s end.

In June 2018, Draghi announced that the ECB was ready to wind QE down. “The Governing Council, he declared, had “concluded that progress towards a sustained adjustment in inflation has been substantial so far.” This was a startling declaration. The core inflation rate was about 1 percent, where it has been for nearly three years. By September, the euro area’s growth slowdown had become manifest, and the ECB revised its growth forecasts down a tick. But Draghi continued to insist that the outlook for growth and inflation remained favorable. At his December press conference, when announcing the end of QE, Draghi presented a bright economic assessment. “The underlying strength of domestic demand,” he said, “continues to underpin the euro area expansion and gradually rising inflation pressures. This supports our confidence that the sustained convergence of inflation to our aim will proceed and will be maintained even after the end of our net asset purchases.” The assessment was disturbingly at odds with the data—with Germany and Italy in near-recessionary condition.

Given this pattern of denials, delays, and half measures, it is not surprising that the ECB’s actions failed to move the euro’s exchange rate against the U.S. dollar. In this manner, the eurozone failed to gain the one benefit of QE that both the United States and Japan had received (Figure 6). Indeed, since the dollar appreciated against other currencies starting in early 2015 as the Fed began a gradual withdrawal of its QE bond purchases, the trade-weighted effective euro exchange rate perversely appreciated after the introduction of the ECB’s QE. Little wonder, then, that the ECB’s QE did little for growth.

The eurozone is in a macroeconomic trap. The lack of significant growth momentum during and following the prolonged global financial and eurozone crises caused a compression of imports. The import compression led to a swing from current account deficit to surplus in countries worst hit by the crisis (Figure 7). That surplus propped up the euro’s exchange value, which, in turn, created a further restraint on growth.

Source: Euro area GDP, Eurostat code namq_10_gdp; Balance of payment, Eurostat code bop_c6_q; Euro area current account, ECB code DD.Q.I8.BP_CU.PGDP.4F_N.

Eurozone growth is driven by world trade

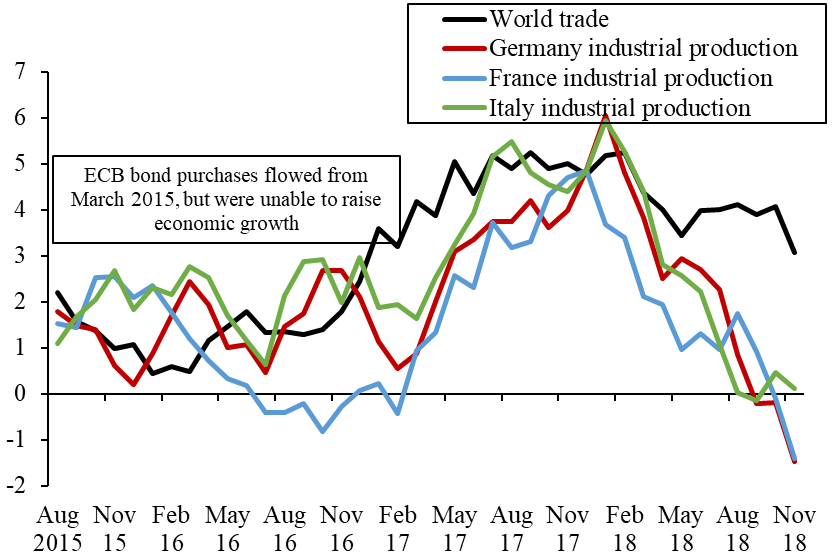

Draghi asserts that the ECB’s “QE has been the only driver of this [euro area] recovery.” To the contrary, the evidence is that QE has made little difference to bolstering euro area growth. Growth in the eurozone remained in the doldrums in the first two years after the ECB initiated QE. In these two years—2015 and 2016—world trade grew at an annual rate of around 3 percent or less. Because European countries are highly dependent on trade, the anemic pace of world trade growth placed a lid on eurozone growth (Figure 8).

Starting in early 2017, Chinese authorities injected significant stimulus to rev up their economy. As has been true in the past couple of decades, rapid growth in China accelerated the pace of world trade growth through stepped-up Chinese imports and greater activity spurred by Chinese firms in global value-added chains. Higher world trade growth, which reached a peak of over 5 percent in late 2017, predictably spurred eurozone growth. Although it is tempting to attribute the higher eurozone growth to a delayed benefit of QE, in reality world trade was doing all the work. Thus, when the Chinese authorities pulled back on their stimulus for fear of aggravating the already alarming domestic financial vulnerabilities, world trade growth slowed and so did the eurozone. Throughout, QE remained a sideshow.

The ECB’s loss of influence has consequences

Hélène Rey is right. The Fed, in effect, sets global monetary policy. The BOJ remains unable to move inflation. While the ECB’s defenders often argue that “things might have been worse” absent its QE program, judged by the benchmarks of other central banks and even those set by its own management, the ECB’s QE has no apparent impact on either inflation, the euro exchange rate, or euro area growth.

Unlike the Fed, the other central banks have lost the “expectations game.” In June 2018, at Sintra, the Portuguese resort town, Fed chairman Jerome Powell noted, “Today policy makers have a greater appreciation of the role expectations play in inflation dynamics.” BOJ’s Governor Haruhiko Kuroda bemoaned that Japanese consumers have come to expect that prices will remain relatively stable, which has made businesses hesitant to raise their prices. Five years of ambitious QE, he helplessly concluded, have failed to dislodge the “tenacious deflationary mind-set” rooted in the Japanese psyche.

As John Williams, president of the New York Federal Reserve, has also emphasized, once inflation falls, it is extraordinarily hard to get it “back up to where we want it to be.”

The ECB’s political limits to monetary stimulus have prevented it from getting inflation back where it should be. The result: much of the eurozone has fallen into a “lowflation” trap. Although no eurozone country is facing outright deflation, lowflation raises the real interest rate, which causes consumers and investors to hold back on purchases, which holds back growth, which validates the expectation that inflation will remain low, which causes consumers to continue holding back on purchases.

Among central banks, the Fed stands out because its commitments are the most credible, allowing it to influence expectations most effectively. In the latest crisis, the Fed began early and did not equivocate until 2013. Thus, the Fed engineered large depreciation of the dollar through QE and slowly but surely brought inflation back to 2 percent. The BOJ undermined its own credibility in the 1990s, when it hesitated in fighting the deflation threat. That loss of credibility has continued to haunt Japan. Even in the latest QE round, despite its ambition, episodic hints of tapering have undermined the BOJ’s efforts. The BOJ, therefore, has been only partially successful: some yen depreciation but little traction on prices.

The ECB has lost the expectations battle and, hence, the ability to raise inflation. Even more so than the BOJ, the ECB is unable to engineer an exchange rate depreciation.

Now, amid a sharp economic slowdown and persistent low inflation, the ECB’s decision to halt its asset purchases renews afresh its cycle of denials, delays, and half measures. Some ECB officials, led by Benoît Cœuré, take comfort in their view that the large stock of past bond purchases will continue to exercise a stimulative effect. This is a strange claim. The marginal transaction, not the stock held, influences the bond’s price and, hence, its yield. Hence, with stoppage of ECB’s new purchases, bond prices will fall and the yield will increase.

That expectation of a rise in euro area interest rates keeps the euro-dollar exchange rate bound in a narrow range even though the Fed has already raised its policy rate from a target range of 0 to 0.25 in December 2016 to a range of 2.25 to 2.5 percent as of December 2018.

A rise in euro area interest rates could prove unbearable in many eurozone countries. Their real interest rates are already rather high, productivity growth rates are very low, and the effective euro exchange rate, stronger than at the start of QE, could become even stronger.

The ECB has reiterated that it could resume QE. At his December 2018 press conference, in response to a question on whether the ECB could “deal with the next economic slowdown,” Draghi responded, “we have instruments.” These are the same words he used when the ECB postponed QE in the crucial 2013-2014 period, allowing lowflation to set in. If eurozone growth remains weak, a hesitant effort to renew QE—amid discordant voices from the Governing Council—will be met with deserved skepticism. It could all be rather unpleasant.

This post written by Ashoka Mody.

Could we do one more post: exactly HOW does China’s M2 pump up everything whilst ECB money went down the drains? What’s THE MECHANISM?

Zi Zi – start your own blog. These comments of yours are both juvenile and just pointless.

This is a rare moment I will semi-defend Zi Zi. I have my own blog and occasionally make comments there if I get super-worked up about something, or want to use vulgarity or words I know most bloggers wouldn’t allow or would filter. Let’s say, of the Katie Roiphe, Camille Paglia, or Laura Kipnis category of scribblings. But I have to say, as someone with an actual blog that comments on OTHER people’s blogs, it’s much funner to make crass and jaded comments when you know they will actually be read.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ebanS7YL6V4

Zi Zi Excellent question. The answer is two-part. Read Mody on the first. He is a go-to expert on what’s happening to Europe.

Europe is irreparably culturally and economically divided. Tied by an unworkable common currency that’s strangling the Southern periphery countries. Putting Italy and Greece especially in a hopeless downward spiral whereby the better-educated, entrepreneurially-able, hope-of-the-future youth are fleeing.

China on the other hand is culturally one. As long as the CP rules, China is also unified economically. China leverages an internationally low wage base, steals intellectual property rights and technology from multinationals domiciled here in the US, and lavishly provides credit (M2) to its export industry to utilize the fruits of its pirating. The shabby tier of Chinese export goods is gobbled up in US Walmarts by illicit immigrants and welfare types who vote taxes onto those who actually do the nation’s work. Ironically, those who have lost their jobs to the hollowing out of America are also driven to the Walmarts in a lesser, additional, yet very real loop of downward spiral. This China pipeline generates an all-in trade deficit of around $350b that cumulatively indebtens the US more each passing year, erodes our manufacturing base potential (present and future!), and in fact helps multiculturate Western Civilization so that it collapses, just as does the flow of illegals across the US Southwest border.

At deeper root the takedown of Western Civilization is what this is all about. Read Mujahid Kamran, The International Bankers, World Wars, I, II, and Beyond on this the larger story.

I noticed neither you nor Zi Zi provided any data on China’s M2. So both of you are just babbling sine a shred of evidence.

Zi Zi and his side kick JBH would have us believe China’s M2 money supply has exploded relative to its GDP. A source on the M2/GDP ratio says it has declined:

https://tradingeconomics.com/china/money-and-quasi-money-m2-as-percent-of-gdp-wb-data.html

Two more commenters who rant about things they have no clue about!

But if we pay attention to M. Kamran, we can find out who shot JFK. Maybe even who shot J.R. Ewing. Always good to know you can get the scoop on evil international bankers—and the fall of western civilization— from a physicist from Pakistan.

Likely the “multiculturating” of this country was irreparably damaged in the 19th century when lots of Irish, Italians, Poles, Czechs, et. Al., flowed across our borders. Never underestimate the negative effects of all those Catholics and Jews on the “uniculture “.

And how about those Chinese and Japanese? What were their accomplishments?

One bright spot: the “unculturating” of the American West where we showed Mexicans and the native peoples who was boss.

Thanks, JBH, for the swell history lesson.

There’s some evidence that the -0.40% interest rate on excess reserves charged by the ECB to member banks operates as a tax that perversely reduces economic activity rather than encouraging it.

Three words one might have wanted to see: demographics, oil, tariffs.

@ “Princeton”Kopits

Oil prices are becoming less and less of a barometer than they once were. If you haven’t seen that then you’re not paying attention. This is another reason why donald trump’s homage to Saudi Arabia and donald trump’s worshipping at the feet of Saudi Arabian royalty strongly hints at more seedy underlying reasons.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eFOyCwCRTgw

I wonder if Tillerson enjoys looking at these old dance videos of him after being curb-stomped by donald trump?? It’s always worth it, giving away your own personal integrity to “run with the big dogs”, eh Rex?? Rex?? Don’t you agree Rex?? Where’d Rex go……??

Interesting point about what ISN’T here, Mr Kopits. Demographics are a flock of very large chickens that are only just arriving; oil & tariffs aren’t important enough to move the needle much. Also missing from the discussion are “immigration” (which I’m guessing is in the oil&tariffs bin of interesting but not really big deal) and [drum roll] “wealth concentration”. ALL of the productivity gains for nearly FORTY YEARS in the U.S. have been commandeered by the elites leaving nothing but credit and population growth to stimulate the consumer behemoth.

In Europe and Japan, demographics have very much arrived, and also to a lesser extent in the US.

I mention tariffs because European industrial production appears to fall off just about when US tariffs were implemented.

I don’t know what Abenomics is expected to achieve when the Japanese workforce is falling as fast as productivity gains.

The appreciation of the dollar against the Euro from mid-2014 is all about surging US oil production and the collapse of the oil price. The current account deficits of the Rest of Europe is largely driven again by oil from 2004 to 2013, and surpluses are materially supported by the collapse of oil prices after 2014.

So I think this whole discussion is way too monetary.

But, ok, I’ll overlook it, if some can give me the answer to this:

If Japan’s population is falling, and it’s workforce is falling faster and can just be offset by productivity gains (ie, no GDP growth trend), then what should we expect to happen to real estate prices? Don’t these suffer secular deflation? If if the value of your house if just going to fall forever, what interest rate pairs with that?

Let’s see who’s the smartest guy in the room.

I am very quickly becoming an Ashoka Mody “fanboy” much in the same way I am a Menzie Chinn “fanboy”. Please don’t make fun of me—I attribute this “fanboy” hero-worship of “dry” professional economists to my socially awkward teen years. Oh wait, I was socially awkward long after my teens. What were we talking about again?!?!?!?

This Ashoka Mody post is very well written and a super-enjoyable read. Certain parts jump out at you.

—ECB not as effective as BOJ (I assume the main focus here is in intentional depreciation of the home currency with trading partners). That’s a pretty bold statement. A strong statement. But it’s really hard to argue with (and I don’t argue it) after Ashoka presents the facts and graphs.

—ECB raised rates in 2011 TWICE. WOW. I don’t even remember this and seems near unbelievable even now looking back at it. Who the F___ made that call?? In April Draghi wasn’t in, and in July Draghi had only been at head of ECB 1 month, yeah?? So we’re to assume this was mostly German influence on the ECB here?? Draghi doesn’t strike me as a guy “pushed around” very easily.

— Sometimes ECB transparency or “tipping off” of the market can be a negative thing, as Draghi cueing markets on QE dissipation kept Euro higher compared to the dollar. First I wanna make it very clear in my little comment here I am much more in Ashoka’s camp than Draghi’s camp on this…….. BUT….. ECB is “forced” to “bullshit” a little in its media pressers to moderate market/public reactions, yes?? I mean….. we can “feel” a little for the predicament Draghi was in, in that even Draghi probably knew he was “bullshitting” sometimes in his ECB media pressers, but still knew he kinda had to “play that game” to make each QE move as effective as he could in the sense of EU/sovereign bond sales and equity markets. Yeah?? Draghi has to keep market sentiment in “non-panic mode” so that equity markets stay steady and the EU/Sovereign bond sales and bond “auctions” continue without snags yes?? It seems lie this is part of the game for him

I remember when everyone thought Greenspan’s speaking was “mysterious”, but I think Greenspan always knew that IF there was “a little surprise” in the Fed moves (similar to if Draghi had waited to announce the QE dissipation instead of showing his QE poker cards in June 2018) the moves would in fact be more “powerful” or “effective”, or have the market “impact” Greenspan was going for. So I do think, depending on individual circumstances, there are times when being transparent is not a good approach. Though I still lean towards central bank transparency overall

Excellent post, Menzie . I’ve read widely on Mody’s website as a consequence. Ordered his book as well. Kudos to you, Askoha Mody!

The first link covers Italy, the last 3 links are Yanis Varoufakis discussing the importance of democracy in Europe.

https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2019-01-31/italy-officially-slides-recession-after-budget-battle-brussels

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v756i2N3lCw

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5vuf6HWKxoY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GB4s5b9NL3I

A living legend. Wonder if Letterman will ever get him on his Netflix show?? “No Introduction Necessary” seems to apply.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBPBFpK3jkQ

Not saying I agree or disagree with any of this. But some interesting contradictory opinions and charts on the current USA market:

https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2019-02-02/markets-are-misguided-betting-fed-done-bond-titan-warns

I don’t foresee the Fed tightening any time in 2019, but it’s not out of the question. If I was forced to wager I would say ZERO rate increases inside of 2019, but it’s not impossible.

Deflation fear seems to be based on theoretical ideas with zero grounding in reality. ” Although no eurozone country is facing outright deflation, lowflation raises the real interest rate, which causes consumers and investors to hold back on purchases, which holds back growth, which validates the expectation that inflation will remain low, which causes consumers to continue holding back on purchases.”. Please show research showing Japanese consumers held back purchases because prices were declining on average by 1%. I do not think anybody in Europe holds back purchases because of low inflation. For one few people think inflation is low. Just look at the Eurobarometer responses. Very few respondents in the only country with some price declines for a while – Italy – thought prices were declining. The only purchases that are sometimes delayed in response to expected price declines are for more expensive goods showing technological progress or fashion (i.e. waiting for the sales season). I.e fear for mild deflation is based on nothing. The Depression was quite different….huge price level declines in a short timespan and 25% unemployment….