The Federal Reserve has increased the size of its balance sheet by a third of a trillion dollars over the last 15 weeks, returning to tools that a short while ago we thought it had abandoned. But the Fed’s current goal in these operations is quite different from what we had seen earlier.

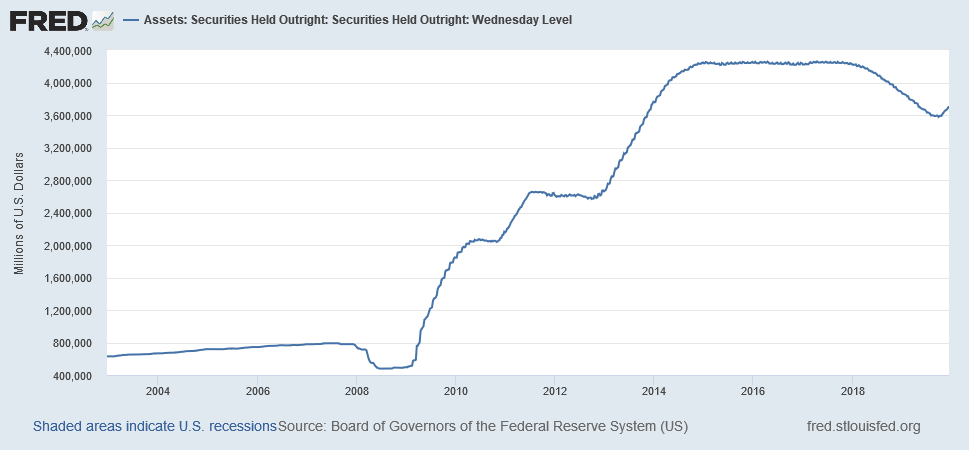

One of the factors causing the renewed growth of the Fed’s balance sheet is the Fed’s direct purchases of securities. By the end of 2014 the Fed held over $4 trillion in securities. At the end of 2017, it began to reduce those holdings gradually. But last summer the Fed returned to a policy of reinvesting maturing assets in order to keep its level of securities constant. And two months ago the Fed resumed net security purchases, causing its balance sheet to grow again.

Securities held outright by the Federal Reserve in millions of dollars, Wednesday values, Dec 18, 2002 to Dec 11, 2019. Source: FRED

The Fed’s goal in increasing its securities holdings through 2014 was to hold down long-term interest rates. The idea was that if the Fed took a large enough volume of long-term bonds out of the hands of private investors, it might increase the market price of the bonds, or equivalently, lower their yield. The empirical and theoretical evidence that this strategy could have a substantial effect on long-term yields remains controversial. But whatever the merits of this theory, it is not the motivation for the Fed’s recent purchases. These have all come in the form of purchases of short-term Treasury bills, not the long-term bonds that the Fed was buying in volume over 2009-2014.

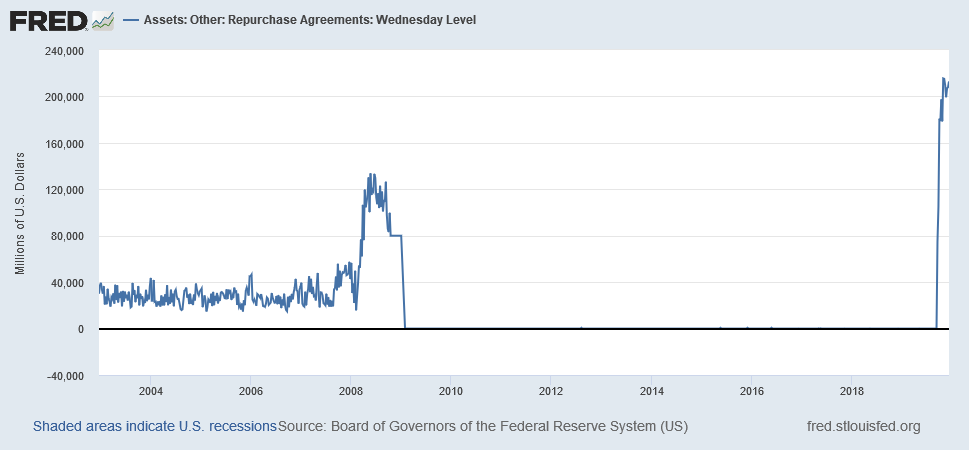

A bigger factor in the resumed growth of the Fed’s balance sheet has been repurchase agreements. These are essentially a collateralized short-term loan from the Fed to primary dealers. Before 2008, the Fed regularly used these to fine-tune its control of interest rates, entering into small repurchase agreements if it wanted to put some additional reserves temporarily into the banking system. In 2008, the Fed greatly expanded the use of this tool as it tried to fight the financial crisis, accepting as collateral for repos some of the assets that banks would have had trouble liquidating in that environment. By 2009, this intervention by the Fed was no longer needed, and Fed repos were essentially nonexistent between 2009 and last September.

Federal Reserve repurchase agreements in millions of dollars, Wednesday values, Dec 18, 2002 to Dec 11, 2019. Source: FRED.

Was the large-scale resumption of these operations last fall a response to some fundamental new distress in the financial system? It may raise some concerns, as I comment below. But the biggest issue it highlights is a point I raised in a recent paper: the Fed currently lacks precise tools for achieving its primary policy objectives.

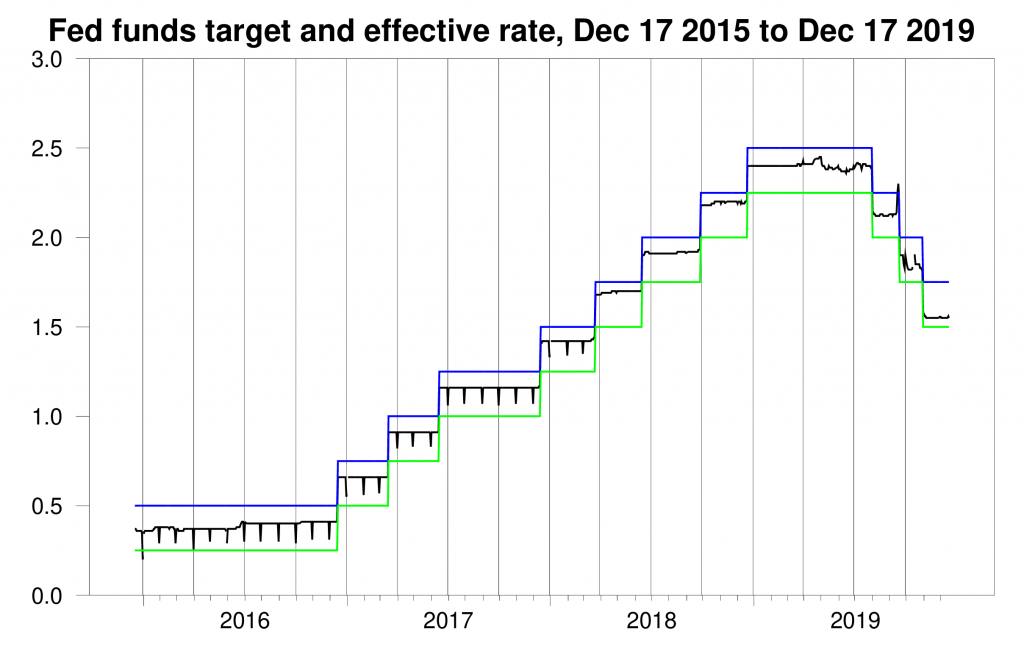

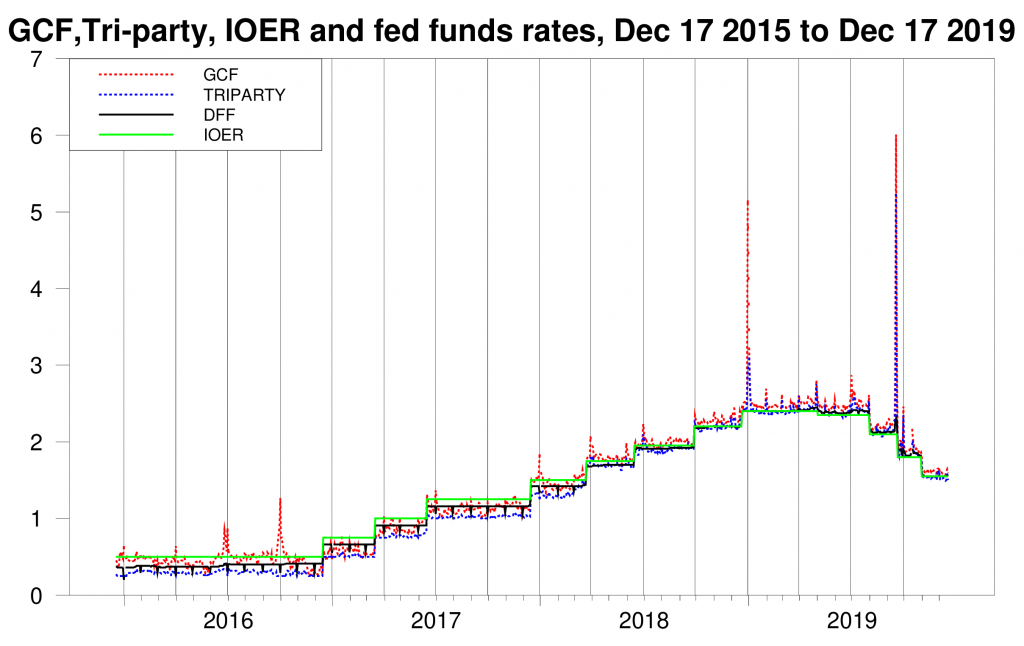

Since 2014, the Fed has announced its objective in terms of a target for the fed funds rate, which is an interest rate on overnight loans between depository institutions. The Fed has framed its objective in terms of upper and lower bounds within which it wanted the fed funds rate to trade. That worked for a while. But last September the funds rate spiked above the Fed’s intended range.

Effective fed funds rate and upper and lower bounds of Fed’s target range, daily Dec 17, 2015 to Dec 17, 2019.

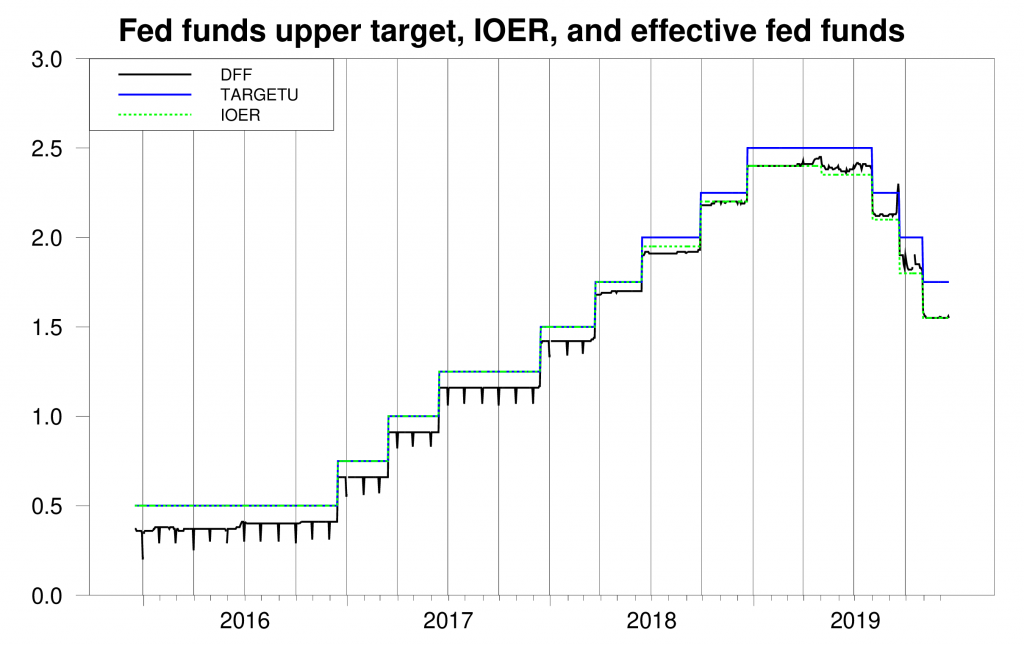

What happened? I predicted this in the paper I wrote last May. You can watch a video of my presentation on YouTube. The basic issue is that while the Fed has been announcing at each meeting an upper target for the fed funds rate, there was nothing guaranteed by its specified policies that prevented the fed funds rate from trading above the target. For a while some might have thought that the interest rate the Fed pays on excess reserves (IOER) functioned something like an upper bound. After all, up until the middle of 2018, the fed funds rate was always below IOER and in fact the Fed always specified the identical number for IOER and its upper target. When the funds rate began to nibble around the value of IOER, the Fed simply raised the number it announced for the target above IOER. But the target itself was just an announcement — there was no automatic procedure to ensure that the goal would be achieved.

Effective fed funds rate, upper bound of Fed’s target range, and interest rate paid on excess reserves, daily Dec 17, 2015 to Dec 17, 2019.

So what was holding the fed funds rate down, if not IOER? In my paper I argued that there were two factors. First, low investment meant limited demand for borrowing, and second, the huge volume of excess reserves in the system was helping keep rates down. I suggested that demand for borrowing was picking up, in part perhaps due to the U.S. Treasury’s need to finance the big deficits, changing the first fundamental. More attractive rates for short-term lending were pulling lending from depository institutions away from fed funds and into other instruments like tri-party repos and general collateralized finance. Rates on these often spike near the end of a quarter due to window-dressing — lenders don’t want to acknowledge who their counterparties are to stockholders or regulators, so they refuse to lend on certain dates. In September those spikes were big enough to bring the fed funds rate up with them.

Daily general collateralized finance rate, for repurchase agreements collateralized by Treasury securities (dashed red), rate on tri-party repurchase agreements collateralized by Treasury securities (dashed blue), interest on excess reserves (green), and effective fed funds rate (black), Dec 17 2015 to Dec 17, 2019. Vertical lines mark end of quarters.

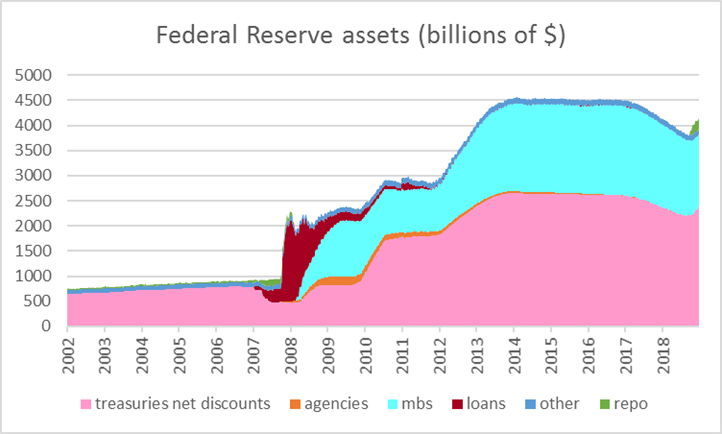

The Fed’s response to this development was to address the second factor I mentioned above, namely, flood banks with even more excess reserves. This was a main objective of the security purchases and the repos. The following graph shows the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet. Repos and new purchases of Tbills brought total Fed assets up by $334 B over the last 15 weeks.

Federal Reserve assets, Dec 18, 2002 to Dec 11, 2019, Wednesday values in billions of dollars. Treasuries net discounts: U.S. Treasury securities held outright plus unamortized premia minus unamortized discounts. MBS: Mortgage-backed securities held outright. Agencies: Federal agency debt securities held outright. Other: sum of float, other Federal Reserve assets, foreign currency denominated assets, gold, Treasury currency, and special drawing rights. Loans: sum of loans, net portfolio holdings of Commercial Paper Funding Facility LLC, Maiden Lane I, II, and III, net portfolio holdings of TALF LLC, preferred interests in AIA Aurora LLC and ALICO Holdings LLC, central bank liquidity swaps, and term auction credit. Repo: Federal Reserve repurchase agreements. Data source: Federal Reserve H41 archive. .

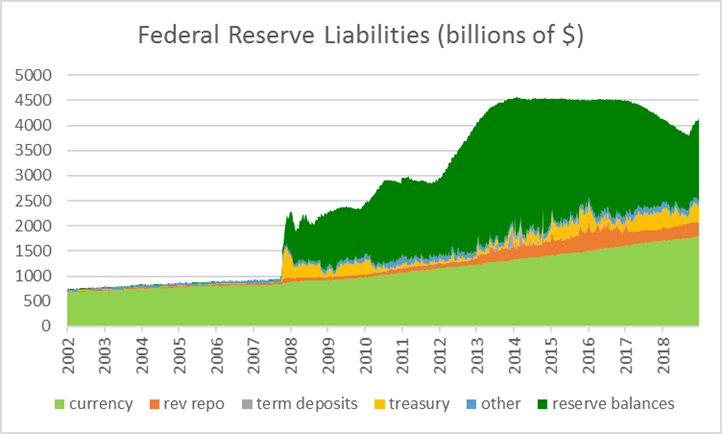

Buying the Tbills and making the repos expanded the volume of excess reserves held by bank, as seen on the liabilities side of the Fed’s balance sheet.

Federal Reserve liabilities, Dec 18, 2002 to Dec 11, 2019, Wednesday values in billions of dollars. Currency: currency in circulation. Rev repo: reverse repurchase agreements. Term deposits: term deposits. Treasury: U.S. Treasury general account plus supplementary financing account. Reserve balances: reserve balances with Federal Reserve Banks. Other: all other liabilities.

And exactly what level of reserves is needed to keep the fed funds rate always below the current upper target of 1.75%? Nobody knows. As I wrote in my paper,

the size of the Fed’s balance sheet is at best a very blunt instrument for influencing interest rates.

There is a way to use repurchase agreements to achieve a precise target. That is to specify an interest rate and offer to do an arbitrarily large volume of operations, whatever it takes to satisfy the demand. If the Fed operates on this basis, it puts an effective ceiling on the interest rate at which any counterparty that is eligible to participate in the facility would borrow. Why pay more to borrow from a private counterparty when I can get all that I want from the Fed? That’s a workable system, as long as the Fed has full regulatory supervision over all the eligible counterparties. But this is not currently the case. And when it’s not the case, it’s hardly a recommended plan for the Fed to assume all private credit risks on its balance sheet, effectively providing the funds for every lending opportunity.

That last point raises a broader issue. We’re seeing a new manifestation of the shadow banking system and its potential instability. By shadow banks I refer to institutions that follow the traditional model of banking, which is to borrow short and lend long. We understand well the vulnerability of such systems to a sudden reluctance of lenders to roll over short-term debt, and we have strong regulations and guarantees in place for traditional banks to keep this from happening. But the private repo rates plotted above are outside this regulation, and their spikes (currently end-of-quarter events) raise some concerns.

My recommendation is that the Fed narrow the list of counterparties eligible for repos, offer to do an arbitrarily large volume of repos at a chosen policy rate, and resume the process of reducing the overall size of its balance sheet.

And keep a sharp eye on the shadow banking system.

Jim,

Thanks for this informative update. Just two questions.

We (or at least I) have seen these reports here and there that since the September repo ruckus the NY Fed has been regularly intervening in the repo markets, and that indeed this was planned to continue to be done at least into January. None of these reports I have seen have been sprecific regarding the nature of these interventions. However, you seem to indicate that they are not now doing what you suggest, or at least not all of it.

So my first question is, “Do you know what these interventions have been and to what extent they follow what you recommend, if at all”?

The second question gets back at the motives for this expansion of excess reserves that you note since the repo ruckus. I could be mistaken, but I do not think you commented on the scattered reports from several sources that the problems in September especially emanated from large banks subject to heightened capital requirements due to the Basel III Accords. Rather here you mention the possible role of the shadow banking system.

So, the second question is, “Do you think the problems in the repo markets have had more to do with new rules for the large commercial banks or more due to various activities going on in the shadow banking system”?

So, Jim, I have reread all this and gone back again to your May paper, where indeed you noted various repo rates going above IOER and thus pushing up fed funds rates starting back in 2018, with spikes at ends of quarters and an especially large one at the end of 2018, which I do not think there was much media coverage of. I also see that there and here you are essentially advocating an open repo out of the Fed, but here you add only for regulated banks, not the shadow banks, which you are concerned about.

I also see you identifying the increased demand for borrowing by the Treasury as a major factor in this destabilization. I did not see any comment there or here on whether the tightened capital requirements for the larger commercial banks due to Basel III Accords, which reportedly camee on in 2018 have played any role or not, as some observers have argued, whose arguments I have reported here without necessarily saying they are correct.

Anyway, I think the answer to my first question is given between your earlier paper and this extension of it. My second question remains unanswered, and I am curious if this is because you do not feel that you know the answer or what. But I am curious regarding your view on this theory that has been put forward by various observers. Needless to say, the increase in excess reserves, especially short term ones and repos, is consistent with that story, but could certainly be happening even if it has not played a role, perhaps indeed if this is driven by the shadow banking system.

I ran into a friend earlier today who is a history prof who told me there is a story in the latest Economist, which I have not seen, about instability in the repo market. Apparently that story poses that there is some “large borrower that is in serious trouble.” That would seem to be consistent with several accounts of this.

Barkely: Thank you for your thoughtful questions and comments.

On your first question, yes the Fed’s been doing big repos, but I’m thinking about these from a different perspective than they seem to be. My proposal is, the Fed picks the rate it wants, and lets the market figure out the quantity. My understanding of what the Fed has been doing is, let’s pick a quantity, and if that doesn’t get the job done, we’ll pick a bigger one. If the Fed could pick the quantity exactly right on target, I suppose you could say the policies are equivalent, though even there, I think there is a stability that is inherent in the system I am proposing, in contrast to the quantity-based approach.

On your second question, I’m not sure of the answer. It is the case that Basel has been one factor in some of the window dressing we’ve seen — banks are required to satisfy certain conditions on some days but not on others. I view that in part as a problem with the design of the regulatory framework, not an issue of the regulations being “too tight.” But window dressing can also result from many private forces at play as well.,

The issue I’m raising about the shadow banking system is more fundamental than end-of-quarter spikes in rates. The issue is the inherent instability of an unregulated financial system that is based on borrowing short and lending long. My view is that we need to identify the areas where we want to protect the broader public from the fall-out when those systems go bad and make sure we have adequate regulations to mitigate those problems and tools to respond if they get out of hand.

+1

“My view is that we need to identify the areas where we want to protect the broader public from the fall-out when those systems go bad and make sure we have adequate regulations to mitigate those problems and tools to respond if they get out of hand.”

Good will from james, but will not happen. Problem is that the regulator and the “to be regulated” are the same. When Obama welcomed the banksters in 2009 to give them the “all clear” after the big crash, James could easily see : profits are privatized, losses are socialized. They are all criminals.

Zoltan Pozsar is one of the better guys to read up on related to this topic, and you can find some (not all unless you subscribe) of his client newsletters in a Google search. I may not agree with everything he says, but “you” (the general reader) will find yourself much more educated on the topic than you were before you read him.

Not to offend anyone, or just be prickly for the sake of being prickly, but I find much of the above to be “boilerplate”. Mind you, “boilerplate” does not mean it’s not 100% accurate, but I feel it’s largely stuff people who are paying attention and read Bloomberg, WSJ, FT etc largely already recognize. The part Professor Hamilton makes that many people are “missing” at the moment, or conveniently hiding under their Persian rugs, is what Professor Hamilton highlights in the last 3 portions of his post:

“That last point raises a broader issue. We’re seeing a new manifestation of the shadow banking system and its potential instability. By shadow banks I refer to institutions that follow the traditional model of banking, which is to borrow short and lend long. We understand well the vulnerability of such systems to a sudden reluctance of lenders to roll over short-term debt, and we have strong regulations and guarantees in place for traditional banks to keep this from happening. But the private repo rates plotted above are outside this regulation, and their spikes (currently end-of-quarter events) raise some concerns.

My recommendation is that the Fed narrow the list of counterparties eligible for repos, offer to do an arbitrarily large volume of repos at a chosen policy rate, and resume the process of reducing the overall size of its balance sheet.

And keep a sharp eye on the shadow banking system.”

That has to do with FUNDING not “liquidity”, and Who, i.e. what parties/type of firms the Federal Reserve provides funding to. When the Federal Reserve keeps providing cheap funding to high risk outfits, and then sheepishly AND coyly says “oh damn, the system is acting funny, there’s ‘nothing’ we can do”, the “experts” who engage in risky behaviors may run to do a TV interview on Bloomberg or CNBC saying “this is a liquidity problem” and some dumb academics may believe them—it doesn’t mean it’s true.

It may also interest some regular readers of this blog to know, when Professor Hamilton discusses “counterparties” which often here would mean hedge funds, that the “counterparties” on the repo transactions with hedge funds would be….. would be…… wait for it…. wait for it….. wait for it…… COMMERCIAL AND INVESTMENT BANKS Oh…..that one hurt so much to read/type “out loud” didn’t it?!?!?!?!? It hurts some people’s head so bad they might feel like they had a severe case of shingles.

Moses,

When are you going to accept that your claim that what is going on here is about “funding” but not “liquidity” is just boguss? As it is, funding is a broader term that included both long term and short term. Liquidity is specifically “short term funding,” simply a one word name for that. If you insist on using “funding,” then please put “short-term” in front of it.

There may be long term funding issues going on in the shadow banking sector, something that Jim H. suggests might be a problem. But he is pretty clear that the end-of-quarter repo ruckus stuff has involved centrally as you quoted him on it “sudden reluctance of lenders to roll over short-term debt.” This is liquidity, and that is why so many commentators talk about these repo market oscillations as reflecting “liquidity crises.” You ain fact recognize that I am not the only one saying that, but somehow have it your head that you are the bigger expert here, and that everybody should start talking about “funding,” and not “liquidity,” while failing to recognize that if they were to do so they would have to say “short term funding.”

Nice.

My recommendation is that the Fed narrow the list of counterparties eligible for repos

But earlier you said: Rates on these often spike near the end of a quarter due to window-dressing — lenders don’t want to acknowledge who their counterparties are to stockholders or regulators, so they refuse to lend on certain dates.

Is there a mechanism by which the Fed’s refusing to accept certain counterparties would make it less likely that lenders will want to hide the identities of their counterparties? Would narrowing the list discourage lenders from lending to risky counterparties?

Also, is this just a US Fed problem, or are other central banks facing the same problem?

2slugbaits: I am not suggesting that the Fed can or should eliminate all spikes in all money rates. Instead, I’m proposing a narrower operating procedure: the Fed chooses a policy rate x and a set of institutions that it wants to guarantee never have to pay more than x to borrow overnight. The Fed can implement that policy by creating an open repo facility at rate x that is available only to said designated institutions. Such a procedure achieves the stated policy objective almost by definition, and has worked fine in practice in a number of countries.

I am not suggesting that window dressing is caused by something the Fed is doing. But it is a symptom of the way the financial system is currently functioning that raises some concerns in my mind. I think the appropriate response to that concern is to look at the overall regulatory structure. Getting the plumbing of day-to-day monetary policy so that it accomplishes the Fed’s objectives is one task, for which I propose the solution is a targeted open repo facility. Identifying potential systemic risks in current financing arrangements is in my view a separate task.

Here are some links that might be beneficial to people. Just for Professor Hamilton’s benefit, I read the specific ZH link and there is no vulgarity in the post, the other two links are Bloomberg, so you don’t have to waste time on the links if you are afraid of obscene material there:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2019-12-17/fed-has-thrown-kitchen-sink-at-repo-issue-bofa-s-cabana-says-video

Tim Clark says, as of 5:00am this morning what I have been saying for MONTHS now. So I’m sure Tim Clark saying what I have been saying for many weeks deserves more respect than coming from me:

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-12-20/don-t-use-repo-market-volatility-to-roll-back-bank-regulations

And the ZH post:

https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/repo-crisis-fades-away-first-time-turn-repo-not-oversubscribed

ZH is usually just Cliff’s Notes of Bloomberg’s posts, so whatever, but the links are not behind a paywall and sometimes their graphs are pretty good.

Mose,

I was not able to read the Clark piece. Which banking regulations does he think should not be undone because of the repo ruckus? Keep in mind that I have not advocated undoing these tightened capital requirements coming from Basel III. I have supported the Fed intervening in the repo markets in appropriate ways to stabilized them. Your ZH report suggests that maybe the Fed interventions have been successful in that regard.

Needless to say Jim’s presentation here and his further comments highlight his specific proposals of how and what the Fed should do, with a key being the effort to really fix a particula rrate while only allowing certain entities to participate in that market. This largely seems sensible, although it may allow some other repo rates to ruckus that continue to be used by the shadow banking system. I do not know the answer to how to deal with that one, but Jim makes it clear that the shadow banking system issue goes beyond the end of quarter repo ruckus stuff, which it seems the Fed can probably manage.

I am worried that this is raw politics. Buying direct from outsiders rather than eliminating cash in the Treasury General Account as the Fed has been doing to offset eliminate their holdings always meant that Treasury had to borrow more to fill up the TGA. This slows down the accelerating growth of the deficit which makes the fiscal mismanagement less obvious. And by pumping new money into the financial system they are supporting the stock market and perhaps also intending to get more real economic activity by an easy-money effect (as its been called).

This supports Trump in an election year.

These are not actions, in my opinion, based on even the theoretical of monetary policy, which this article highlights as being poorly understood. These are more political in nature.

These actions related to new purchasing while halting its offset elimination of TGA funds should be more openly discussed. And challenged.

JF,

Not likely. It is and has been the job of the Fed to try to stabilize the banking system and to keep both th rate of inflation and the unemployment rate low. That always helps whoever is the incumbent president. II is certainly the case that Fed policies have political implications, but that does not mean that what the Fed does is just “raw politics.” This instability of the repo markets is something that the Fed would never like and would try to do something to stabilize, no matter who is president.

More interesing and arguably political is Jim H.’s argument that an important driver of this instability has been the increased budget deficits arising from Trump’s fiscal policy. One might want that the Fed do nothing about this and let banks fail and have a recession so as to politically punish Trump for being a naughty boy. But the Fed simply does not so such things, or has not since the time of Volcker in any case, when in fact we had a high rate of inflation.

The financial system and credit and money creation are interwoven, certainly, and the Fed cares about their role. The Fed discovered during the financial crisis that credit creation by the primary level of banks helped to fuel markets for Treasuries and they discovered also that the Quantity Theory of Money was mythology (to pick my own word here). They now understand that they need to encourage the maintenance of high reserve levels and that the huge Fed balance sheet of Public securities and the maturation pace of these securities and their ability to roll these amounts over via the Treasury auction itself (not by purchases from private parties) provides them with stimulating mechanisms for the financial system. The change in their redemption/maturation policies in July and then a month later reflects this discovery. This helped Treasury hold on to cash making the Trump fiscal policy less stark ($50 B a month?) while the Fed auction buying by the Fed keeps yields/rates lower. If SOMA buys more Treasuries from the private sector in coordination, this too primes the pump.

These are huge changes, and strongly accommodating – all at the request of this Administration, or certainly it meets the needs expressed by this Administration.

The mechanisms that might fit a theory of money and monetary policy, appear to be more practical in nature as the notion of monetary policy is that it is more mythology than valid.

I think all of this should be more openly brought out to public view (thankful for this blog, though it’s focus on the repo mechanisms are minor matters, more focused on the roots of the trees rather than the forest itself).

Right now the Fed asserts they can offset-Eliminate cash in the Treasury. I have no idea why this is appropriate.

Think what would happen if Treasury says it does not agree to this accounting offset and instead tells the Fed to hold the cash they give it on redemption? Is the Fed an instrumentality of the public? Would this cash on the Fed books then be owned by the public? Why can’t it be used to pay lawful claims (contractor invoices, grant program disbursements, social security, etc.). Why does the public need to borrow the monies in order to shuffle it back to themselves (indeed the Fed created the money out of whole cloth during QE).

Light of day is needed here.

This all seems like the emperor having no clothes parable. And even though I support the Fed (and believe the austerity economics notions are sinister) what they are doing is more supportive of a dynamic economy and repudiates all these myths of economics, I want the light of day brought out more here.

It just seems that there is something very wrong here.

I don’t see the support. Debt expansion ending makes a crash likely in 2020…as been predicted since 2014.

Everything else aside, it looks to me like the Fed is doing its job. Whether it benefits Trump or somebody else is irrelevant.

Re Barkley’s question: According to the Pozsar pieces Moses Herzog mentions, Basle 3 Liquidity Coverage Ratio and the need for intraday liquidity for resolution purposes are the key regulatory drivers. Large US banks (really just a couple) no longer have excess reserves despite the appearances. Thus, when overnight repo spikes (mostly trading among investment banks and hedge funds) they are holding back from lending, which would (and did before reverse QE) cap the spikes. The system lacks a ‘lender of next to last resort’.

Question for Jim: what do you mean by restricting repo counterparties? Does that mean to primary dealers that are also part of BHCs that are covered by Basle 3, cutting out the few that are not like Jeffries or Cantor?

Pozsar’s proposal was to set up a standing facility for BHC’s so that they could freely repo their Treasury holdings for reserves, thus effectively making Treasuries as good as reserves in their HQLA portfolios. He’s got a Bloomberg podcast (Odd Lots?) on this. Something like this seems inevitable if the Fed wants to control the whole money market complex of rates.

Uh oh, tom. Santa Uncle Moses might give you a lump of coal. You are not to say that any of this has anything to do with the Basel III Accords. He has been very clear on this, even if others say that it is. You are a naughty boy.

@ Barkley Junior

Santa Moses has extra sweets and toys under the tree for you this year Junior, since this is possibly the very first time you didn’t misquote him. Santa Moses wants to encourage you not to tell lies in order to justify your god-complex or in an attempt to win arguments, so Santa Moses reinforces good behavior with the presents you asked for. However….. Santa Moses cannot promise you a Copmala Harris vs Biden “showdown” in South Carolina like you predicted. Even Santa Moses has his limitations.

Well, toodle-loo to all the immature seniors in Virginia, Santa Moses will be very busy soon, and he will go have a long talk with Bob Dole, where we both continually refer to ourselves in the 3rd person.

https://youtu.be/BqmDRh7XmSI?t=55

tom: I am talking about excluding even some primary dealers from the open repo facility that I am advocating. A completely open repo facility is only a reasonable plan if the Fed has unambiguous supervisory authority over the asset and leverage decisions of its counterparties. That is not the case for all primary dealers, and is certainly not the case for all counterparties currently eligible for reverse repos with the Fed.

Likewise, I am not advocating that the Fed try to control the full range of all private repo rates. I am suggesting the Fed should implement day-to-day monetary policy in terms of a specific, achievable target and think separately and more broadly about the regulatory environment and potential threats to financial stability from outside the regulated banking system.

Professor Hamilton,

regarding liquidity and interest rates, any thoughts about the recent article by Julian Kozlowski, “Tail Risk: Part 3, The Return on Safe and Liquid Assets”?

https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/economic-synopses/2019/08/07/tail-risk-part-3-the-return-on-safe-and-liquid-assets

@ AS

It obviously implies rates will be low for quite awhile. If we look at the incredibly high levels of corporate debt right now, it makes sense. Investors and savers are putting a higher premium on the safety component, and therefor are willing to accept a lower rate of return on bonds for the relative safety compared to equities etc. This isn’t going to change for the foreseeable future, so if we are just looking at this from the safety component ALONE it predicts rates will be low for a long time. Odds are inflation will remain low for the next 2–3 years (outside of major events such as war), this also implies low rates. Could they move up slightly?? Yeah, but from my viewpoint a 1% move up inside of a year would be HUGE. So, just to not be a wussy about it what do I mean?? I think the 10 year Treasury is a good measure. It’s roughly 1.92% right now. If the 10 year treasury went ABOVE 2.92 between now and December 2020 (excluding extremely short terms spikes) I would be very shocked. That’s not a prediction “per se” as I don’t think I can say it with 100% certainty, but I am saying I would be very shocked if it got above 2.92% anytime before December 2020.

How useful is that information in a market context at this point?? Not very. The only example I can think of at the moment is if some real estate broker was trying to pressure you or hoodwink you into believing you should “lock in” low mortgage rates now. Now, I think fixed rates are nearly always the way to go, but if someone like a real estate broker is telling you low rates won’t be available 2-3 years from now, I think I would tell them they are full of c***. I’m sure there’s other examples, but not many I don’t think.

None of the above comment is expert/professional advice. Just Joe six-pack at the keyboard.

Dear Professor Hamilton and others,

It seems implied by Jim Hamilton’s argument that the Fed purchases are keeping rates from going above 1.75%, if I am reading this correctly. Is there any possibility that these purchases are a signal to the market, more than day-to-day monitoring, that come trouble, the rates will not fall much below 1.75%, a type of insurance if you will?

Julian