Today, we are fortunate to be able to present a guest contribution by Stéphane Dees (Banque de France and Univ. Bordeaux) and Alessandro Galesi (Banco de España). The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Banque de France, Banco de España, or the Eurosystem.

In 2014, the then Vice-Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Stanley Fisher, declared that “actions taken by the Federal Reserve influence economic conditions abroad. Because these international effects in turn spill back on the evolution of the U.S. economy, we cannot make sensible monetary policy choices without taking them into account.” Owing to the international role of the US dollar in the international financial system, the US monetary policy is currently a major determinant of the global financial conditions, giving rise to the emergence of a global financial cycle, documented for instance by Hélène Rey . Oscar Jordà and co-authors also show that the influence of the US monetary policy on global equity markets has increased during the 20th century and reaches today an unprecedented level.

The US monetary policy as a driver of the global financial cycle

Since US monetary policy endogenously responds to the global consequences of its own measures, the natural question is to what extent the role of US monetary policy in driving the Global Financial Cycle gets amplified by spillback effects and, more generally, by the complex network of cross-country interactions that arise in a highly integrated global economy. In a recent paper , we tackle this question by assessing the international spillovers of US monetary policy with an estimated global VAR (GVAR), a multi-country empirical framework which models the global economy as a network of interdependent countries. The model allows to investigate whether the effects of US monetary policy shocks get amplified by the complex network of interactions among receiver countries, as well as by spillback effects from countries in the rest of the world to the US. We identify US monetary policy shocks using theory-based sign restrictions on selected responses of US variables, while at the same time leaving unrestricted the responses of all variables in the rest of countries in order to allow for an agnostic identification strategy about the size and sign of international spillovers. We explicitly consider both conventional and unconventional monetary policy measures, the latter intended as a broad mix of measures and communication aimed at affecting the yield spread while leaving at the same time the policy rate unchanged.

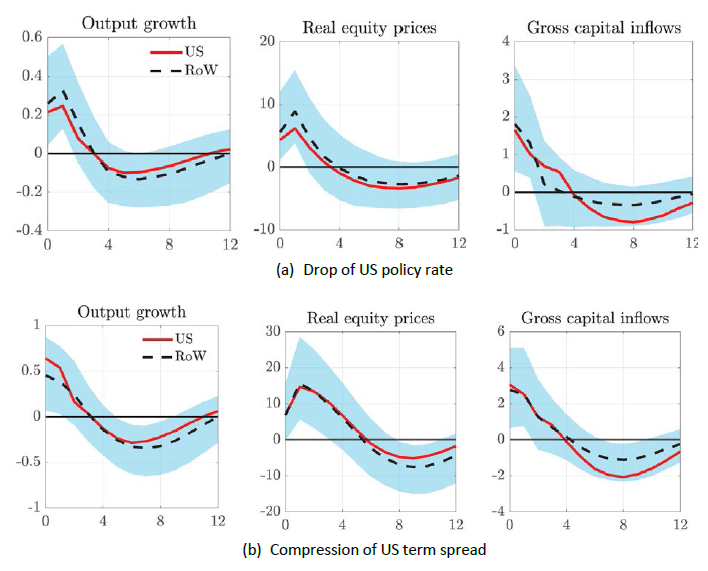

An easing of conventional monetary policy shock in the US improves financial conditions by raising equity prices and gross capital inflows, and stimulates macroeconomic activity. More importantly though, the US monetary easing triggers a risk-on environment featured by surges of capital inflows in the rest of the world and increases of international equity prices. As a consequence, global GDP growth increases. The presented evidence gets further support when focusing on the international transmission of an unexpected flattening of the US yield curve. Again, the monetary easing boosts international capital flows and equity prices, thereby increasing global growth. Importantly, macro-financial spillovers are economically and statistically significant even in economies with floating exchange rate regimes and, if anything, having a flexible exchange rate provides just a partial insulation to foreign shocks.

Figure 1: Domestic and global effects of easing conventional (a) and unconventional (b) US monetary policy shocks. Notes: median responses for the rest of the world in dashed black, joint with 16th and 84th percentiles, and median responses for the US in solid red, to an expansionary US monetary policy shock which either decreases on impact the US short-term rate by 25 basis points (panel a), or which decreases on impact the US term spread by 25 basis points (panel b). x and y axes measure quarters and percentage points, respectively.

Disentangling the network effects of international spillovers

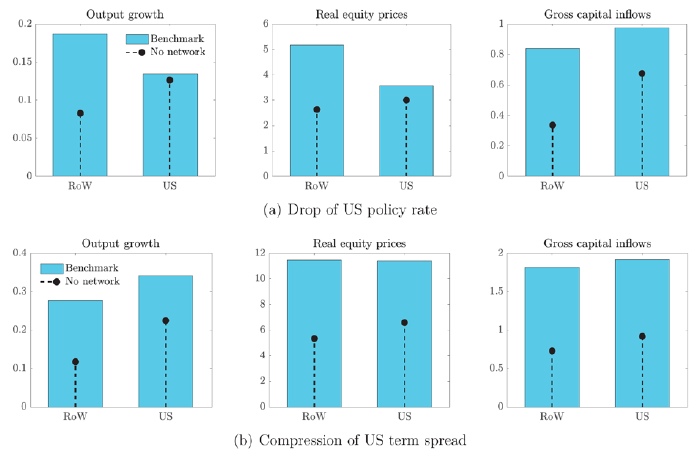

To what extent does the complex network of interactions across countries reinforce those effects? This can be measured by comparing the estimated effects with those arising from a similar US monetary policy surprise estimated from a model that does not account for network effects. In other words, the alternative specification lets the US monetary impulse affect all countries altogether, but precludes the shock to propagate among receiving countries (third-country effects), as well as any second-round effect from the rest of the world to the US economy.

The results are striking: network effects roughly double macro-financial spillovers of expansionary US monetary policy shocks, regardless of whether the easing is undertaken via conventional or unconventional measures. In particular, a 25 basis points drop in US policy rate implies an increase in global growth by 0.19% when network effects are taken into account against 0.08% without network effects. Similar results arise with a 25 basis points compression in the US yield spread (0.28% with network effects and 0.12% without). In the same vein, network effects lead to roughly doubled increases in global equity prices and capital inflows. Interestingly, network effects also amplify the domestic effects of US monetary policy shocks, and particularly so when considering compressions in the US yield spread. The boost in domestic growth induced by the monetary easing is about 0.22% without network effects, and it averages 0.34% when network effects are in place. The corresponding figures for US equity prices are 6.6% and 11.4%, respectively without and with network effects. These results confirm the view that international effects of US monetary policy sensibly spill back onto the evolution of the US economy itself. Overall, we find that the role of US monetary policy in driving not only financial but also macroeconomic activity on a global scale gets amplified by the complex network of cross-country interactions.

Figure 2: The role of the network for domestic and spillover effects. Notes: average one-year effects for the rest of the world (RoW) and United States to a US monetary policy shock which decreases either the US short-term rate by 25 b.p. (panel a), or the US term spread by 25 b.p. (panel b). Benchmark: baseline model with network effects; No network: the shocks affect all countries, but excludes third-country and second-round effects. y axes measure percentage points.

Changes in network effects over time

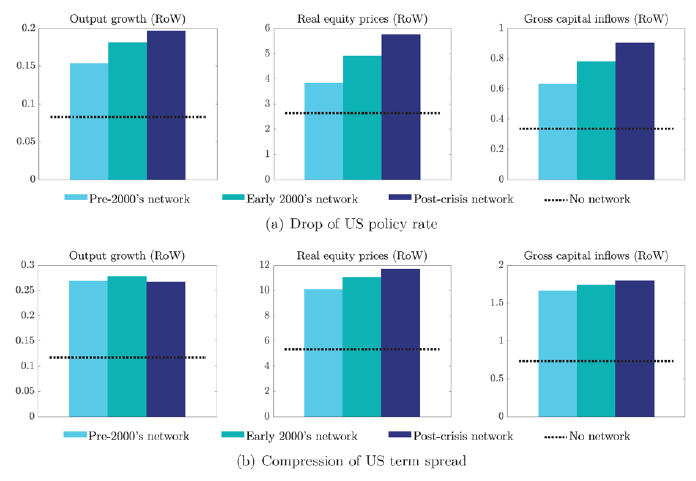

Have the changes occurred in the network structure over the last decades had an effect in shaping the size of global spillovers? Figure 3 reports the spillover effects on the global economy (excluding the US), to the two types of expansionary US monetary policy surprises. Two results are worth pointing out. First, network effects tend to amplify the spillover effects of US monetary policy, regardless of the type of the network structure and of whether the easing is undertaken via conventional or unconventional measures. In fact, the model without cross-country network implies systematically smaller effects than those obtained by the alternative versions that account for both bilateral interactions among receiver countries and spillback effects to the US economy. Second, the amplification of the network tends to increase as the network evolves over time, and especially so in the case of a conventional policy rate drop.

Figure 3: Spillover effects and the evolving role of the network. Notes: average one-year effects for the rest of the world (RoW) to an expansionary US monetary policy shock which either decreases on impact the US short-term rate by 25 basis points (panel a), or which decreases on impact the US term spread by 25 basis points (panel b) for the model which exploits data on average bilateral trade flows over the years 1994-1999 (Pre-2000’s network), over the period 2000-2007 (Early 2000’s network), over the period 2008-2016 (Post-crisis network), and for the model which precludes network effects (No network). y axes measure percentage points.

With the pre-2000’s network structure in place, a 25 basis points drop of the US policy rate boosts global growth and equity prices by 0.15% and 3.8% respectively. The same figures are higher and average nearly 0.20% and 5.8% with the most recent post-Great Recession network, and a similar picture arises regarding the effect on global capital flows. Overall, these findings suggest that the evolution of the network is an important driver of the increasing role of US monetary policy in shaping the Global Financial Cycle.

Conclusions

The recent view of the Global Financial Cycle has emphasized the existence of powerful financial spillovers of US monetary policy to the rest of the world. Since US monetary policy endogenously responds to the global consequences of its own measures, its role in driving the Global Financial Cycle gets amplified by spillback effects and more generally by the complex network of cross-country interactions that arise in a highly integrated global economy and this amplification increases as countries get more globally integrated over time. Our research suggests that the evolving network is an important driver for the increasing role of US monetary policy in shaping the Global Financial Cycle. Although the channels through which countries interact are several, complex, and still not fully understood, our analysis highlights that accounting for such a network of cross-country interrelationships is a sensible dimension to consider in the current debate.

This post written by Stéphane Dees and Alessandro Galesi.

This looks reasonable. The one issue i see not addressed is why interest rates are so much higher in the US than in many other high income nations. Clearly this is an entrenched, dare I say “equilibrium”?, situation coexisting with this ser of network effects. But it is curious.

Looks like that Stanley Fischer guy knew what the hell he was talking about. This site is very strange, next they’ll be quoting Olivier Blanchard or something…….. damed heretics…..

*damned

Jean Tirole, one of my personal favorites (had some of his books before he got the Nobel, as I also had Krugman’s (How many kids read Krugman’s books before they graduated college?? Not many where I’m from I can tell you). Anyways, never let it be said Uncle Moses never gave you a early Christmas gift:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t_5Liz1YveE

Dear Moses, many thanks for the link. Great speech indeed (in an institution where I spent more than 15 years of my professional life…). I like a lot what he says about climate policies (a topic I’m working on now at Banque de France).

Thanks again for the gift!

Stéphane (co-author of the post)

: ) No doubt a great place and a great man. I have some small peeves with ECB, but no place is perfect and no place that large can reflect anyone’s personalized version of “ideal”. It’s a mammoth task the ECB and its great staff undertakes. For me (what Americans refer to as “a bleeding heart liberal”) people like Mr. Tirole and yourself embody the very best parts or quintessence or kernel part of economics as a life labor. How to use the resources and bounty “God” or “nature” provides in a way that is fair to all, and provides enough for those on “the lower end” of society. And yes, without killing off incentives in the process. I am not being facetious when I say, when sincerely undertaken, it is something to be admired.

BTW, I have a warm spot/affection to French economists as they tend to tilt left in their views. But that’s a subjective preference on my part—not an empirical measurement. : )

Talking rates, 22 minute program:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JL3QgKSyKRw