Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Hongyi Chen, Senior Advisor at the Hong Kong Institute for Monetary and Financial Research, and Pierre Siklos, Professor of Economics at Wilfrid Laurier University.

There is a long tradition in economics suggesting that each country’s economic policies should be governed by the motto: “keep your own house in order”. For example, the textbook depiction of a flexible exchange rate is that it acts as an absorber of external shocks thereby allowing each country to independently set monetary policy. Indeed, this can explain why small open economies such as Canada have supported floating exchange rates the longest. However, even policy makers in Canada have recognized for some time that exchange rate shocks produce distinct effects on goods markets than in financial markets (Dodge 2005).

Of course, the extent to which international linkages are tight or loose may be critical but, under certain assumptions, Obstfeld and Rogoff (2002) demonstrated that the gains from monetary policy coordination are small. More recently, it is the revival of interest in differential monetary policy conditions (e.g., see Howorth et. al. 2019), prompted in large part by the finding that the neutral real interest rate has fallen in large and systematically important economies (e.g., U.S., Eurozone, U.K., and Japan; see Holston, Laubach and Williams 2017), that has led to renewed interest in the policy coordination question. Clarida (2018) argues that, if the decline is truly global and policy rates are partly set according to ones in foreign economies, substantial economic benefits from coordination might accrue. But there are potential negatives to policy coordination in the form of potential losses in central bank credibility and new challenges to central bank communication (e.g., see Bordo and Siklos 2016).

In “Oceans Apart? China and Other Systemically Important Economies” we explore the extent to which the G4, which consists of the US, the Eurozone, Japan, and includes China, as a block contributes to global economic performance. Panel factor vector autoregressions (VARs) are used because these seem well suited to exploit cross-border links and assess the relative impact of domestic and global factors. We find that domestic and global shocks can reinforce each other. Next, we conclude it is essential not to treat China as an exogenous entity in global macro models if we are to better understand how shocks can interact with each other in the G4. For example, a tightening of domestic monetary conditions results in a global deterioration in real economic conditions because spillovers can reinforce the tightening among the systemically important economies. This same shock also leads to global tightening of financial conditions. Indeed, almost 60% of the variability of the global monetary shock can be explained by shocks in a global commodity factor and real economic factor. However, the findings are more muted when shocks from China are treated as exogenous. We conclude, at least empirically and for the sample considered, that there are net benefits from greater policy coordination.

How do we reach this conclusion? A couple of examples from the paper are used to illustrate the point. Readers are asked to look at the paper for additional calculations and estimation details.

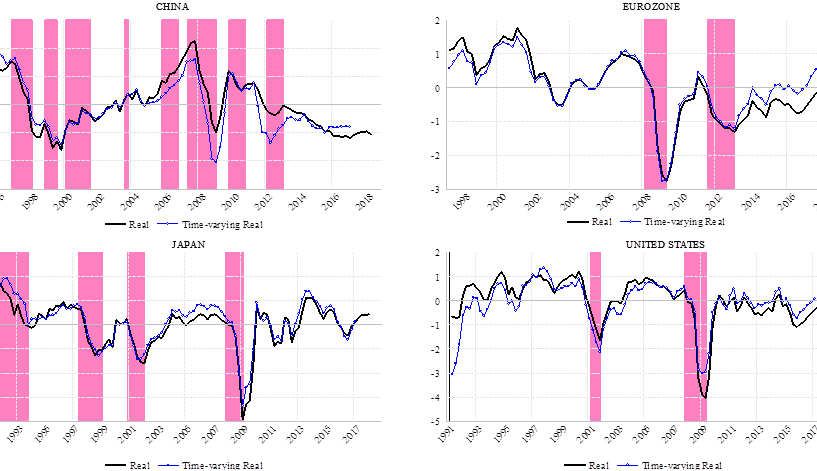

Two figures below show factor scores for the G4 estimated using two different approaches, namely based on the full sample and using a time-varying method. The first figure shows the results for the real economy. A higher value is akin to an expansion in economic activity; a lower value represents, of course, the opposite. Whether full sample or time-varying estimates are used the message is broadly the same. There is considerable commonality in real economic conditions in the four economies.

Figure 1 Real Economic Conditions (i.e., Factor) in the G4. The shaded areas indicate recessions as estimated by the NBER (US), the JCER (Japan), the CEPR (Eurozone), and growth slowdowns in China (ECRI).

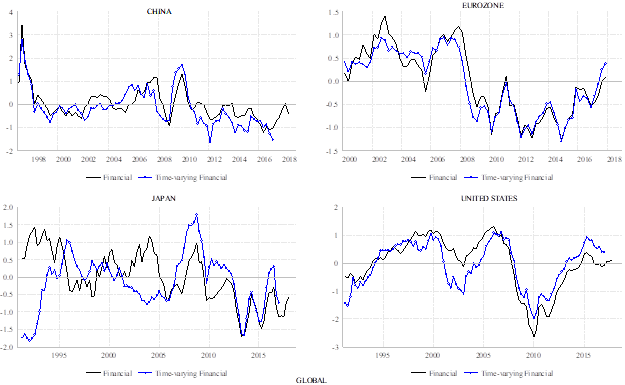

Figure 2 Financial Conditions (i.e., Factor) in the G4.

Matters are considerably different when financial conditions are examined. A rise signifies a tightening of conditions while a decline implies looser financial conditions. Now, not only can time-varying and full sample estimates be quite different but there is far less commonality in financial conditions across the four economies. We also find similar results when observable macroeconomic time series are used instead of the factors. Other stylized facts and econometric estimates result in similar interpretations.

When we add other factors (a monetary and a commodity factor), not to mention examining the difference between the case where shocks from China are exogenous versus a model where shocks from China are endogenously related to the rest of the G4, the picture that emerges from the panel VAR estimates is that spillovers, especially the global component of shocks, amplify domestic shocks. Incorporating a role for commodity prices and financial conditions also raises the relative importance of the global component of shocks when China is treated as a systematically important economy. The finding that China, when treated as part of the ‘club’ of systemically important economies, amplifies the impact of various shocks, notably real and financial shocks, is perhaps not surprising. However, differences from the impulse responses obtained when China is viewed as contributing only exogenously to the interactions between real, financial, and monetary shocks among the U.S., Japan, and the Eurozone suggest that transmission mechanisms in large economies have been significantly impacted by the rise of China as a global economic power.

The link to the paper: https://www.aof.org.hk/docs/default-source/hkimr/working-papers/full-textbd4d93cdb6534e2dabecd94f81f7190f.pdf?sfvrsn=5b0f2b45_2.

References

Bordo, M., and P. Siklos (2016), “Central Bank Credibility: An Historical and Quantitative Exploration”, In Central Banks at a Crossroads: What Can We Learn From History? Edited by M.D. Bordo, Ø. Eitrheim and M. Flandreau (Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press), pp. 62-144.

Clarida, R. (2018), “The Global Factor in Neutral Policy Rates: Some Implications for Exchange Rates, Monetary Policy, and Policy Coordination”, BIS working paper No. 732, July.

Dodge, D. (2005), “Monetary Policy and Exchange Rate Movements”, remarks by the Governor to the Vancouver Board of Trade, 17 February, available from www.bankofcanada.ca.

Holston, K., T. Laubach, and J. Williams (2017), (2017), “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants”, Journal of International Economics 108 (S1): S29-S75.

Howorth, S., Lombardi, D., and P. Siklos (2019), “Together or Apart? Monetary Policy Divergences in the G4”, Open Economies Review 30 (April): 191-217.

Obstfeld, M. and K. Rogoff (2002), “Global Implications of Self-Oriented National Monetary Rules.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 117: 503-36.

This text written by Hongyi Chen and Pierre Siklos.

My problem with China’s “exogenous” influence on America has NEVER been low inflation. I’m much more “pro low-inflation” than credentialed economists are. My problem with China’s exogenous impact on America (and other nations, Eastern and Western) is its driving down of the working man’s wages. The orange creature drives this into the ground when he’s campaigning (which explains many things, about Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania while Hillary tells everyone how incredibly lucky they are she gave them NAFTA). This is one thing donald trump gets right when he’s campaigning.. While “middle class” Joe is trying to figure out which one is his wife, which one is his sister, and in the year 2020 where on his arm he’s supposed to disperse his coughs at. HINT for “middle class” Joe and the Barkley Junior generation: Not in your hands where you turn right around and touch everything.

Biden and I are different generations. He is, like Bernie, a Silent. I, like Trump, am a Boomer.

This is sort of like you thinking that UK was or is affected by what the ECB does and tha Brexit somehow influences that, about as well informed.

@ Barkley The Self-absorbed

Are you sure?? I still would have guessed you’re about 10 years older than Biden. Can you still tell the difference between your sister and wife?? That would be the real tie-breaker.

This is becoming ridiculous, Moses. You are the one initiating attack after attack on me, most of them highly personalistic, and nearly all of them seriously idiotic.

So, since you are demanding personal information from me, most of which is in fact a matter of public record for anbody wanting to waste their time checking all of tis out, I shall on this site waste everybody’s time stating the simple facts.

I was born on April 12, 1948, so I am 71, about to turn 72 on Easter. This makes me a front–end Boomer, a bit behind both Trump and Hillary, but basically in with them. My wife was born on September 7, 1954.

My sister was born on January 29, 1942. She died of a brain aneurysm on 9/11/19. Her daughter, Erica Werner, was the top reporter on the front page of WaPo for the last four days as the top WaPo reporter on Congress.

Want more? For a botom line, anybody reading this can go read my Wikipedia entry to see who I am. “Moses Herzong” is a fake name. I and members of my family are world historical figures; Moses, you are a zero.

@ Barkley Junior

Sure….. as a crotchety old man, you’re rough around the edges, but you needn’t work this hard to cover your deep love for me. I know you love me already. Alas, I have no affection to you. I told you, that moment we were sitting together in that garden, that you were just too much of a self-absorbed type for my taste.

Many ladies in very unhappy marriages like to watch soap operas. Barkley, perhaps these soap operas can help calm you and help alleviate your unhappiness. You can watch this when you’re thinking of me:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qUw2o89EkCI

Interesting paper:

https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/91/5/1255/4597253

Two Lectures related to consumption of Vitamin D and respiratory infections in general.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fmDng_uMCnY&feature=youtu.be

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2pyp9VwFR4s

It’s also interesting to note, that as people get older, it’s harder for their bodies to convert sunshine into Vitamin D. So, theoretically I assume this would mean the eating of Vitamin D then becomes more important, but I don’t know if this same thing happens for older people with the Vitamin D they consume/eat.

I hesitated putting this up as it could be helpful to Barkley Junior. I decided since the overall impact could be positive, it was worth letting one or two Amalekites know about this. I mean, what can you do??

The CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis

publishes some interesting data on world trade and industrial production.

https://www.cpb.nl/en

This is a cool little site. Looks like a shiny little data gem. Thanks for sharing the link.