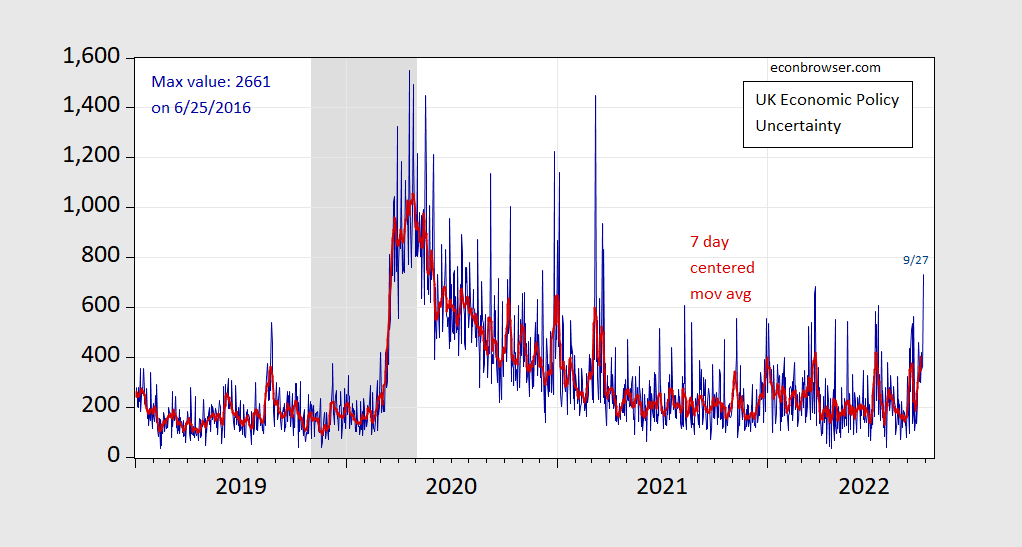

In some ways, policy uncertainty — at least as measured using text — is not as bad as I would’ve thought. Here’s the Baker-Bloom-Davis index:

Figure 1: UK Economic Policy Uncertainty (blue), and centered 7 day moving average (red). ECRI defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: policyuncertainty.com, ECRI and author’s calculations.

The 9/27 value of 732 is way below the Brexit referendum value of 2661. On the other hand…tomorrow is another day!

Since mid-May (chosen more or less at random), There is one currency that has performed about as badly as GBP, though the loss started earlier and has been more gradual:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=UgOd

JPY has a big rate disincentive against just about everybody, so weak performance is to be expected. Note that CNY, as a basket currency, is doing about what you’d expect. CNY weakness against the USD isn’t really a sign of weakness; it’s just math.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/27/opinion/uk-pound-inflation-mortages.html

September 27, 2022

Why Is the Pound Getting Pounded?

By Paul Krugman

Financial markets usually give wealthy, politically stable nations a lot of fiscal space. In particular, a country like the United States, or for that matter Britain, can normally run quite big budget deficits without creating a run on its currency. This is because investors typically believe that nations like ours will, in the end, get their acts together and pay their bills; they also believe that central banks like the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England will do whatever it takes to prevent deficit spending from setting off runaway inflation.

In fact, deficit spending in an advanced economy normally causes the value of that country’s currency in terms of other currencies to rise, because the collision between fiscal stimulus and tight money leads to high interest rates, and these high rates attract an inflow of capital from abroad. When Ronald Reagan cut taxes while increasing military spending during the early 1980s, the dollar surged against other major currencies, like Germany’s Deutsche mark (this was long before the creation of the euro):

https://static01.nyt.com/images/2022/09/27/opinion/krugman270922_1/krugman270922_1-jumbo.png?quality=75&auto=webp

Reagan’s strong dollar.

But a funny thing (or not so funny, if you’re British) happened over the past week, when Liz Truss, the new prime minister of the United Kingdom, announced a neo-Reaganite “fiscal event.” (She didn’t call it a proper budget, because that would have required issuing fiscal and economic projections, which probably would have been embarrassing.)

It was already clear that the Truss government was going to have to increase spending in the short run, to aid families hit with higher energy bills stemming from Vladimir Putin’s de facto natural gas embargo. Rather than raising taxes to help cover this expense, however, Truss’s chancellor of the Exchequer — basically her Treasury secretary — announced tax cuts, notably a big reduction in taxes on the highest earners.

The parallel with Reaganomics was obvious. Interest rates duly rose. But in this case, rather than rising, the pound plunged:

https://static01.nyt.com/images/2022/09/27/opinion/krugman270922_2/krugman270922_2-jumbo.png?quality=75&auto=webp

A loss of Truss?

This wasn’t the market reaction you’d expect for an advanced economy. It was instead similar to what you often see in emerging markets, where investors worry that governments will cover increased deficits by printing more money, causing inflation to accelerate.

Now, such things have happened in Britain before. Back in 1976, Britain experienced a sterling crisis, in which concerns about budget deficits caused a plunging pound, adding to already-high inflation. Humiliatingly, the government was forced to turn to the International Monetary Fund for a loan, which came on the condition that the government make deep cuts in public spending.

At the time, however, the Bank of England wasn’t the independent institution it later became. It was, in effect, just a branch of Her Majesty’s Treasury, and it accommodated the inflationary impact of deficits rather than acting to offset them. These days, the bank is not only independent; it has a mandate to keep inflation low.

So why the sudden run on the pound?

Krugman ably posed the paradox that had left me wondering. Now if the BofE was expected to go all Volcker, one would think the pound would have appreciated like the $ did some 40 years ago. Of course Krugman noted the UK experience in 1976 where the BofE did not raise interest rates. Is this what the market is expecting this time around?

Often, discussions of rates as they affect currency markets are simplified by leaving out the transition from lower to higher rates. That transition is to be avoided, because it involves a price drop. Short bills are fine because they adjust pretty seamlessly, but anything with much duration should be sold, then re-acquired after the price drop. The immediate response to rising rate hike expectations is selling duration. Buying at higher yields comes a bit later. Even if you trust Truss, you would have sold duration. If you thunk she and Kwarteng have created greater risk for little reward (except to those in high tax brackets), then you sell even more duration. Duration is risk.

I am surprised the Krugman did not bring up the elephant in the room I see. That would be Brexit, which has turned into a full blown disaster on many grounds; Crucial parts of it remain unresolved, and the old hope of a deal with the US has not happened and does not look likely.

The problem with Truss on this is that while she was originally a “Remainer,” like various supposedly “moderate” Republicans in the US who have gone full Trump scheiss craziness, Truss has taken extreme positions on the remaining unresolved problems with the EU, which is, after all, Btitain’s largest trading partner.

The really sticky point on this has to do with Northern Ireland, where Boris Johnson just prior to his removal, was working on undoing the very difficult deal he has worked out with the EU on that difficult location. He was on the verge of blowing up major agreements and even violating the law on this. And Truss’s position? If anything she has pushed an even harder line on this difficult matter, although I have seen some reports maybe she is backing off a bit, maybe.

Anyway, UK is now seriously isolated. Biden in particular is ticked off about all this messing with the Northern Ireland agreement, not to mention playing a protectionist game himself to hold off the Trumpists playing to white working class males in the Rust Belt, So, no deal there. Commonwealrth nations are rushing to become republics. And the EU is super ticked off. They have nobody outside to back them up, as their inside seems to be falling apart.

Wonder how MMT fans will explain what is happening in the UK. Whether Kwartang is dim enough to believe his own sales pitch is beside the point – all he did was promise to run up the fiscal deficit in a country that issues debt in its own currency. What could go wrong?

In the absence of a good MMT explanation, there is a little story which might help…

I’ve mentioned recently concern among market participants about the potential for liquidity problems in U.S. Treasury trade. The Treasury market is often touted as the deepest and most liquid market in the world – most often and most loudly by Treasury officials, so make what you will of that – but that has not always been enough. “Highly liquid” is not the same thing as always liquid enough, and we’ve just seen an example of that in the UK fixed income market.

Kwarteng (and Truss) made a seriously bad mistake in giving away money to rich people on an ideological basis, but apparently that isn’t all that went wrong in the gilt market. There are anecdotal reports (too soon for official reports) of three pension funds (perhaps more) receiving margin calls due to loss of collateral value as gilts sold off. Those margin calls amounted to around GBP100 million each. That’s million with a M. Small change in a normal market trading session.

Meeting those calls required unwinding of trades and selling of assets. Among the assets they sold was long gilts, pushing prices down further and lowering the value of collateral further. Unexplained sharp price declines spooked buyers, and on the spiral went.

That’s what a liquidity problem looks like from the inside. However, nearly everyone is on the outside, absolutely blind. The BoE could intervene quickly because, like the Fed, they have a very good information-gathering system. They may have known who was in trouble as it happened, maybe not, but they undoubedly saw the symptoms and knew that liquidity had disappeared. The BoE wasn’t entirely blind.

The same thing can happen in the U.S. It did happen in October 2014 and in late 1998. In neither case was the Fed running down its asset portfolio, nor had Treasuries been loosing value at an historically rapid pace. It is, perhaps, a good thing for the U.S. that the UK ofered a reminder of what can happen. The Fed may boost surveillance (probably already had) and do some dry runs and call-arounds, just to be ready.

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/politics/donald-trump-seeks-end-to-rape-accusers-defamation-lawsuit/ar-AA12mnxk

This is a defense that only Rick Stryker could cook up. Trump rapes a woman years ago, becomes President, and then decided to verbally attack his victim as “not his type”. Of course, an employee of the Federal government cannot be sued for defamation so I guess he never raped her. MAGA!

Much of the comment from mainstream economists regarding the Truss/Kwarteng mini(sic)-fiscal-event has been quite critical. Center, left or right, it doesn’t much matter. A common criticism is that stimulus at a time of full employment is more likely to induce inflation than growth. Tyler Cowen has another unflattering spin on the “don’t call it a budget” – not all fiscal expansion amounts to fiscal stimulus

https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2022/09/the-economy-that-is-british.html

When government absorbs the cost of fuel price hikes on behalf of households, that’s just a transfer, not stimulus, says Cowen. On this point, I think he ignores a big issue in the distribution of borrowing between households, government and business, which is that government can function as borrower of last resort when other sectors turn from spending to saving. Household spending is more sensitive to debt service than is government spending, at least in developed economies. Cowen also points out the distortionate aspects of subsidizing purchases of a scarce commodity, and there I agree.

Interestingly, Cowen also says tax cuts for the rich aren’t stimulative because the rich mostly save the extra money. That’s a heck of an admission from a conservative economist. Happy to see Tyler get such a big issue right.

Anyhow, identifying the fiscal expansion in the Truss/Kwarteng plan as “not stimulus” sort of helps explain the market response to (rejection of) the plan.

Whenever it fits Bruce Hall’s MAGA agenda he tells us all about Tyler’s post but not this one. Wonder why.

I agree this is expenditure, but by no means is all or even most of it “stimulus.” As Josh notes, the energy price subsidies are the biggest part of this announced plan. I am against that policy, but it is trying to absorb a contractionary shock rather than being stimulus per se. The Truss plan is transferring much of that higher energy cost from the private sector to the public sector. The real cost involved is mostly the preexisting problem from the higher cost of energy, which now is on the government’s books to an increasing degree.

Oh yea – Tyler is dismissing the MAGA agenda here so Brucie now goes all silent.

Wednesday was bad in Asian markets. The UK isn’t the only country intervening. Risk appetite is low, which means less money is looking for short-term opportunities to buy beaten-down assets.

This iss essentially Bloomberg, without the paywall:

https://www.yahoo.com/news/plunging-markets-trigger-intervention-warnings-091301474.html

Wonder if that flight from the UK and Asia fueled U.S. gains.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/29/business/economy/economy-gross-domestic-product.html

September 29, 2022

U.S. Economy Weaker Than Thought in Year’s First Half, by One Measure

Gross domestic income, adjusted for inflation, grew more modestly than first estimated. Unlike gross domestic product, though, it remained positive.

By Ben Casselman

Conflicting Signals

Revisions brought two measures of output closer together, but it still isn’t clear whether the economy is shrinking or growing.

https://static01.nytimes.com/newsgraphics/2022-09-27-gdp-revision/f0baf088ad25c3177be022a2fad2378c4f6de70c/_assets/gdp_v_gdi-600.png

A key measure of U.S. economic output grew more slowly in the first half of the year than previously believed, government data released Thursday showed.

Gross domestic income, adjusted for inflation, grew at a 0.8 percent annual rate in the first quarter of the year and barely grew at all — at just a 0.1 percent rate — in the second, the Commerce Department said Thursday. That was sharply weaker than the 1.8 percent and 1.4 percent growth rates reported in earlier estimates.

Gross domestic product, a better-known measure of inflation-adjusted output, shrank during both periods, at a 1.6 percent rate in the first quarter and a 0.6 percent rate in the second. Those figures were unchanged from earlier estimates.

Taken together, the two measures suggest economic growth was at best anemic in the first half of the year. At worst, the economy had been shrinking for two consecutive quarters, a common, though unofficial, definition of a recession….

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=UhYb

January 30, 2020

Real Gross Domestic Product and Real Gross Domestic Income, 2020-2022

(Percent change)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=Ui5u

January 30, 2018

Real Gross Domestic Product and Real Gross Domestic Income, 2017-2022

(Percent change)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=lSwT

January 4, 2018

Manufacturing and Nonfarm Business Productivity, * 2000-2022

* Output per hour of all persons

(Percent change)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=lSwU

January 4, 2018

Manufacturing and Nonfarm Business Productivity, * 2000-2022

* Output per hour of all persons

(Indexed to 2000)

Alito v. Kagan!

https://www.cnn.com/2022/09/29/politics/alito-supreme-court-kagan-roberts/index.html

Justice Samuel Alito says criticism of the Supreme Court is going too far. “It goes without saying that everyone is free to express disagreement with our decisions and to criticize our reasoning as they see fit,” Alito, who penned the decision reversing Roe v. Wade last term, told The Wall Street Journal on Tuesday. “But saying or implying that the court is becoming an illegitimate institution or questioning our integrity crosses an important line,” he said. It is rare for a justice to issue such a statement when asked for comment about an ongoing controversy, but continues a year in which justices have spoken openly about the court’s public stature since overturning Roe and issuing other controversial opinions earlier this year.

Justice Elena Kagan in several appearances did talk about the court’s legitimacy, and Chief Justice John Roberts seemed to push back on her comments without mentioning her by name during a talk earlier this month. In a series of appearances, Kagan – without directly addressing the blockbuster cases last term – spoke about how courts can damage its legitimacy. “I think judges create legitimacy problems for themselves – undermine their legitimacy – when they don’t act so much like courts and when they don’t do things that are recognizably law,” she said in New York earlier this month. “And when they instead stray into places where it looks like they are an extension of the political process or where they are imposing their own personal preferences,” she added.

I’m with Kagan on this. If Alito does not want to be questioned – he should act like a judge and not a right wing politician.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS30

Market Yield on U.S. Treasury Securities at 30-Year Constant Maturity

30 year government bond rates have increased quite a bit of late so it is no surprise that 30 year mortgage rates have also risen. You heard this from consistently ever since they have risen by 5.13%.

Of course we have a few RECESSION CHEERLEADERS here who lie about everything including about what I have said in the past. Keep this in mind the next time one of the liars goes off.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MORTGAGE30US/

30-Year Fixed Rate Mortgage Average in the United States

Freddie Mac updated its weekly (Thursday) reporting with the latest being 6.7%.

Of course Princeton Steve has to characterize this in a rather profane way. No Stevie – interest rates may be rising but they are not “pretty stiff”. Clean up your language when reporting on financial markets.

The junior Senator from Texas is a flaming racist. How do we know? This scumbucket actually suggests that a President who actually cares about the rights of Hispanics is the racist. Yea he is counting on the racism and stupidity of the MAGA crowd.

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/politics/watch-sen-ted-cruz-has-livid-laundry-list-of-why-he-thinks-biden-is-racist/ar-AA12masg

as of this morning my only position valued in the uk pound has been liquidated for us$.

Funny, because pound has recovered its value to where it was before Truss announced her tax plans, and this with BoE massively buying bonds and pushing interest rates down hard. Plenty weird.