In a recent Milwaukee Journal Sentinel article (via Pulitzer) Rick Barrett notes “Manufacturing is coming home” to Wisconsin. Does the data support this?

The April 2021 [anti-dumping] ruling from the U.S. International Trade Commission became a seminal moment in a business trend called “reshoring,” which is the return of work from overseas to a company’s home country. The reasons could include trade wars and tariffs.

Reshoring could be occurring, and manufacturing could be booming. At the national level, this appears to be the case, as discussed in this post.

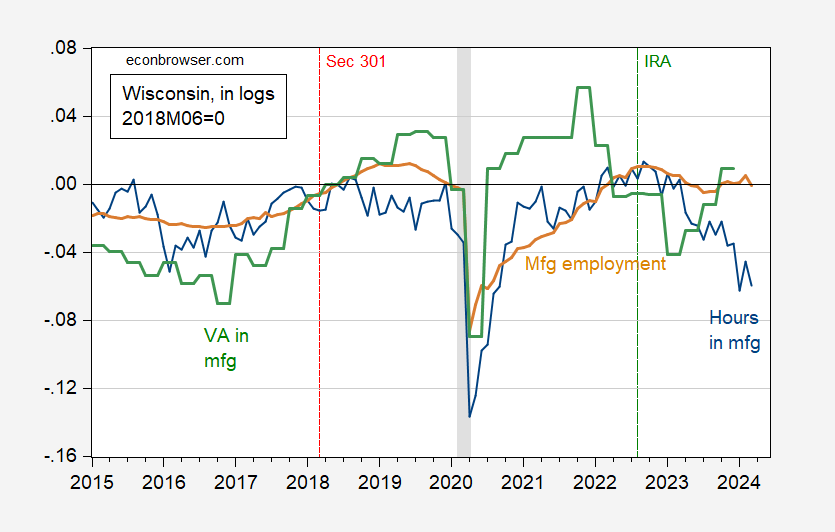

For Wisconsin, the data is more ambiguous. And in any case, I’d be wary of attributing whatever bounce-back there is to tariffs. First, the data, normalized to 2018M06, just before the implementation of Section 301 (market access/China) tariffs.

Figure 1: Manufacturing hours worked (blue), manufacturing employment (tan), and real value added in manufacturing (green), all in logs, 2018M06=0. Hours worked calculated by multiplying employment by average weekly hours. Value added in 2017$ spliced to value added in 2012$ using 2018 ratio. NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Red dashed line at 2018M03, notification of Section 232 and Section 301 actions. Green dashed line at passage of Inflation Reduction Act. Source: BLS, BEA, NBER, and author’s calculations.

Note that employment and value added were rising before the imposition of tariffs in the Trump administration. Similarly, all series were rising before the 2021 antidumping action mentioned in the article. Value added peaked in Q4, the same month when the Stoughton plant expanded capacity, which might be coincidental timing. Since then, value added has declined. (Value added is calculated based on factor payments in Wisconsin, but price cost margins and taxes at the national (sectoral) level — hence, its a little problematic to infer too much from movements in this series. There is no “manufacturing production” index at the state level as a counterpart to the national level series calculated by the Fed).

In general, it’s hard to associate heightened manufacturing activity in Wisconsin with specific trade policies. As the article notes, it could be onshoring due to supply chain concerns that obscures — or even drives — trends in manufacturing (I myself would think the dollar’s value and domestic macro influences might as important).

How about Wisconsin exports (keeping in mind that there the statistics do not capture all the value added coming from Wisconsin)?

Figure 2: Manufactured commodity exports from Wisconsin, bn1999$, seasonally adjusted by author using X-13, at annual rates (blue). Nominal exports divided by manufactured goods export price index. NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA, BLS, NBER, and author’s calculations.

Wisconsin’s manufactured exports (as reported) are indeed about 10% higher than pre-pandemic. But after the imposition of tariffs, exports actually fell for a while — possibly due to retaliation by other countries against the Trump imposed tariffs.

One caveat about thinking about how tariffs would cause higher employment is to realize that while tariffs on some goods (say steel) might cause higher employment in the steel industry, the resulting higher cost of steel — both domestically produced and foreign produced — will raise costs of production in downstream industries (think washing machines, cars), tending to reduce employment there. This is true even if there is no retaliation by our trade partners.

As an aside, thinking about steel tariffs, we don’t make raw steel in Wisconsin, but we do (or did) make some vehicles (MRAPs e.g.).

That reasoning (based on empirical estimates) is why Cox and Russ concluded the net impact of the Trump tariffs was to reduce overall employment.

In the above, I have not provided a comprehensive answer regarding whether employment and output is higher because of tariffs. In order to do so, one would have to use an input-output model to track how tariffs have raised costs of inputs into Wisconsin’s production (of manufactured goods, etc.), and factor out other things like domestic demand, exchange rate fluctuations, and economic growth in the rest-of-the-world. One would likely want to know how much exports declined due to trade retaliation spurred by our tariff actions.

A coalition of U.S. trailer manufacturers, including Stoughton, had prevailed in their complaint that Chinese companies were selling trailer chassis in the United States for below the actual cost of making them, a trade violation known as dumping, that unfairly harms competitors. Soon, import tariffs of more than 200% would be levied on those Chinese trailers, which are used to haul ocean-cargo containers on American highways. Sales would swing back to the U.S. manufacturers, supporting thousands of jobs in Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Alabama and Texas.

I would say a 200% tariff is really steep!

One way to look at dumping is as a gift. If they give us a product at a price less than the cost of making it they have given us a gift. The individuals in this country who are not going to make those specific products being dumped, can instead make some other products. That seems to me as a win-win. Nobody goes unemployed and we get more products.

There are some situations where the dumping can become problematic. If it is used to gain a monopoly on specific products and then prices are jacked up, that would be bad. However, if manufacturing of trailers can easily be revamped, then that’s not a big deal. The same for “strategic” products where the flow of low price (gift) products may be used as a power play in case of conflict.

Dumping is really only a problem (and much less of a gift) if we have high unemployment. Then it will indeed cost us in form of loss of jobs and productivity, because those people losing work are not able to find other productive jobs.

“One caveat about thinking about how tariffs would cause higher employment is to realize that while tariffs on some goods (say steel) might cause higher employment in the steel industry, the resulting higher cost of steel — both domestically produced and foreign produced — will raise costs of production in downstream industries (think washing machines, cars), tending to reduce employment there.”

The tariff on trailer chassis would also raise the cost of transportation in the US which could increase the cost of production for domestic firms.

Speaking of manufacturing jobs in Wisconsin – Biden is in Racine today to announce a $3.3 billion investment by Microsoft to build a new artificial intelligence (AI) datacenter in Racine, creating 2,300 union construction jobs and 2,000 permanent jobs over time. (yes- it is in the now empty field left behind by the failed Walker/Trump Foxconned deal.)

During Trump administration Racine area lost 1,000 manufacturing jobs while during Biden admin the area has added 4,000 manufacturing jobs. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/05/08/fact-sheet-president-biden-to-highlight-3-3-billion-investment-in-racine-wisconsin-and-how-his-investing-in-america-agenda-is-driving-economic-comebacks-in-communities-across-the-country/

Thanks much Menzie

Nice balanced look at an important problem. It seems that the future of manufacturing in our state and nation will follow long term paths, with less labor being employed, more technology and robotics and higher returns to capital . It would be nice if I were wrong.

On the other and, the investment in AI data and processes that Microsoft will make in Racine at the Fox Conn sight is a big step in the right direction

I am not sure how much worth it is to fight over who gets to weld together clunky metal boxes and sell them at (or below) cost. Most of our manufacturing has been moved out of the country already, and we would be unable to compete with foreign low cost producers in the world markets . The real debate should be about keeping everybody employed, not giving them specific jobs of little strategic value. Sooner or later most manufacturing will be taken over by Robots. At that point it becomes beneficial to place the fully automated (jobless) plants close to where the consumers live. So in a few decades manufacturing will be back in the US again, regardless.

Maybe there won’t even be manufacturing plants. You just go to Home Depot and pick up that 3D-printed shovel you ordered on-line a few hours earlier (hot off their printing machine in the back of the store). Or they may have one on display and as soon as you pay for it at the register, the printer in the back starts printing a replacement.

@ Tom, @ Ivan You guys are intentionally trying to depress me, right?? I refuse to use the automated registers at Wal Mart and other stores. That’s my retard “contribution”. “People’s touch” still means something to me, aside from employment and sense of self-worth it gives people/

Let me cheer you up then. Turns out that the savings on automated registers are not working out as promised. Both honest errors and theft is increased at those registers. How much error/theft loss do you need before that $15/hour employee begin looking like a bargain. Also since you need both people stocking shelves, and manning registers, there is a certain flexibility build in when both types of work are needed and one is quite flexible. Workforce retention and satisfaction goes up (pay down) when people don’t have to do the same thing all day.

Only half a tiny can of beer left, but Ivan, you still made me smile.

: )

Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) had a great presentation yesterday.

https://siepr.stanford.edu/events/associates-meeting/geopolitics-and-its-impact-global-trade-and-dollar

You can find the presentation on Youtube.