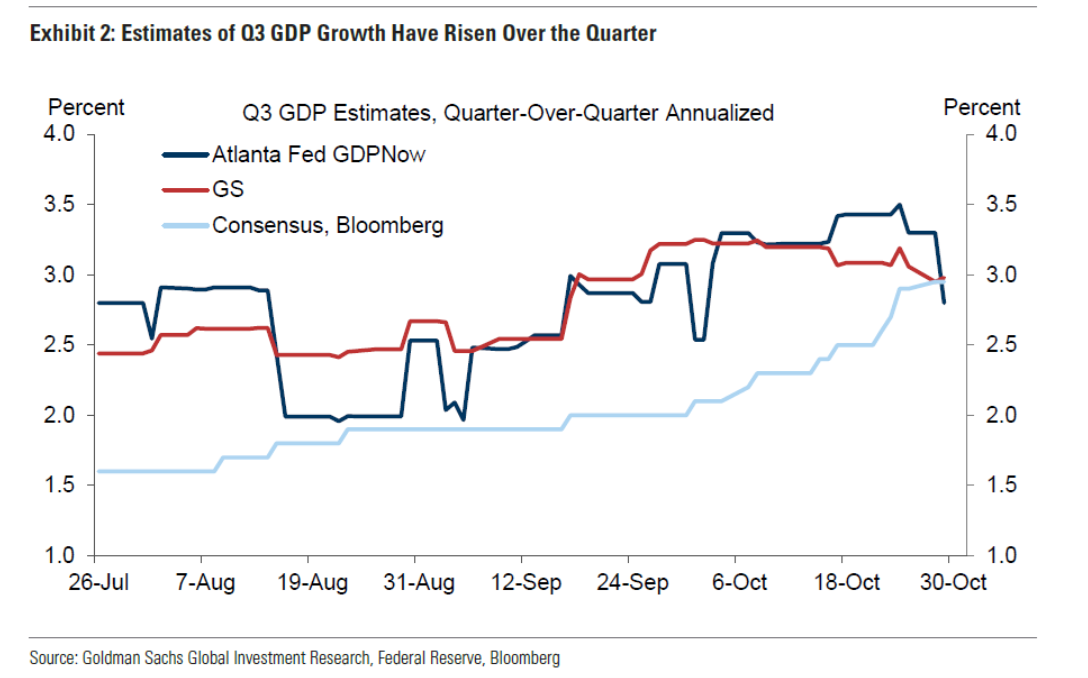

Never just look the headline number. The “why’s” matter. GDPNow down from 3.3% q/q AR to 2.8%, while GS tracking at 3.0%

.

Source: Rindels, Walker, “US Daily: Q3 GDP Preview,” Goldman Sachs Global Investor Research, October 29, 2024, Exhibit 2.

2.8% or 3% is less than earlier nowcasts, but still way above recession levels (think EJ Antoni, who thought the recession might’ve started in July or August).

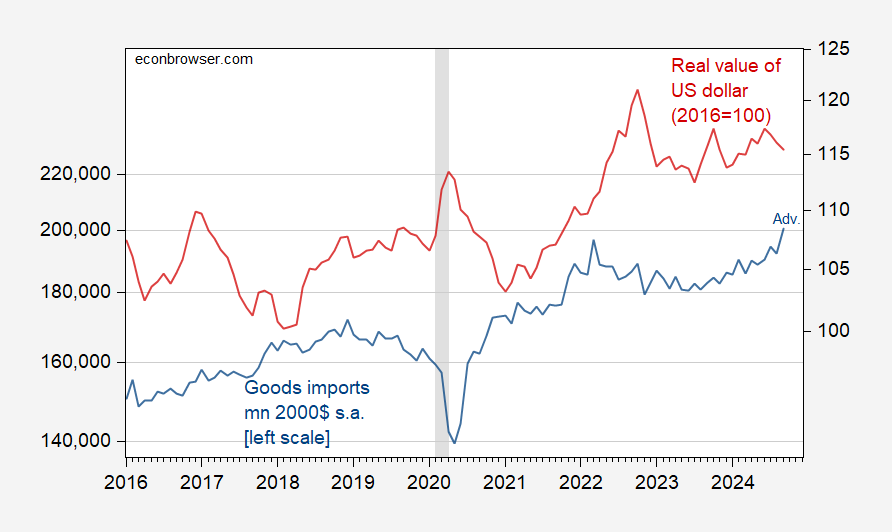

If one looks at the GDPNow forecast evolution (as of 29 October 2024), one sees that a big reason for the decline in nowcast is bigger imports. How does one interpret this?

Interpretation highlights the difference between accounting and economics. A higher growth rate of imports (not due to exchange rate appreciation) presumably means faster growth is expected now and in the future (more imports for consumption and investment where both are forward looking variables). However, a push up in the nowcasted level of imports holding constant nowcasts of the other components of GDP (GDP ≡ C+I+G+X-IM) means that the nowcast of GDP is lowered (h/t my old colleague at CEA Steve Braun for teaching me this).

Here, imports surprised on the upside. From the advance economic indicators release today:

Figure 1: Real goods imports, in mn. 2020$ (blue, left log scale), and real value of the US dollar (red, right log scale). Deflation of imports using BLS price of imports of commodities. NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: Census and Federal Reserve via FRED, NBER, and author’s calculations.

So, this quarter’s numbers are down, while the implied growth rate (ceteris paribus) is up for next quarter.

“a big reason for the decline in nowcast is bigger imports. How does one interpret this? Interpretation highlights the difference between accounting and economics. A higher growth rate of imports (not due to exchange rate appreciation) presumably means faster growth is expected now and in the future (more imports for consumption and investment where both are forward looking variables).”

Economic theory also suggests lower tariffs would lead to more imports. But of course Bruce Hall cannot phantom this possibility because Kelly Anne Conway told him not to.

I notice that as the current account balance as a percentage of GDP has gone from positive up to the 1980s to increasingly negative, GDP has continued to grow.

Are we moving up the comparative advantage ladder?

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1xi6Y

AS: I think of comparative advantage as a determinant of the composition of trade, while macro factors (saving, investment, exorbitant privilege) determine the CA balance.

Our host has said the right thing here but let me take this a little further. Reagan’s fiscal policy dramatically lowered the national savings rate, which raised real interest rates but only partially offsetting investment. The high interest rates also led to a massive dollar appreciation that lowered net exports.

Fast forward to the Clinton years where an investment boom outstripped our modest national savings which again led to dollar appreciation and a large current account deficit.

That takes care of the first 20 years. I’ll leave it to others to discuss the next 20 plus years.

Mortgage rates are back to 7%. Mark Zandi offers this explanation:

https://x.com/Markzandi/status/1851233037595578412

The fixed mortgage rate hit 7% yesterday. Just a few weeks ago, it was flirting with 6% and appeared headed into the 5s. The mortgage rate is up despite the Fed’s decision to cut the federal funds rate by half a percentage point and signal that more cuts are coming. What’s going on? First, the strong economy is even stronger than anticipated, causing investors to re-think how quickly the Fed will cut rates. Equally important is investors’ rising expectation that former President Trump will win re-election (look at betting markets). Investors are taking Trump at his word and believe if he wins it will lead to higher tariffs, immigrant deportations, and deficit -financed tax cuts in a full employment economy, all of which means higher inflation and more government borrowing. The recent surge in mortgage rates is a clear indication what investors believe a Trump victory would mean for the economy and the nation’s fiscal outlook.

Are they reading this blog at the WSJ? They actually got something right!

A Tariff War With China May Be Good News for Brazil’s Crops

https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/markets/a-tariff-war-with-china-may-be-good-news-for-brazil-s-crops/ar-AA1t9kkt?ocid=msedgdhp&pc=U531&cvid=55b1073eba724200bf9ceac73d69f8e5&ei=15

A Trump election win may lead to new tariffs on China, potentially causing farmers to lose billions of dollars as trade gets redirected to competing nations like Brazil. Former President Donald Trump’s proposed policy changes promise to place tariffs of 10% to 20% on all imported goods – although that range has varied at different times during Trump’s campaign. Trump also threatens to escalate existing tariffs on Chinese goods with a 60% tariff on all Chinese imports. These new tariffs may spark retaliation from China, which is the largest trading partner for U.S. agriculture. Reigniting the trade war that raged during Trump’s first term may give China more fuel to find other suppliers for their agricultural needs. “If a trade war were to occur between the USA and China, the competitiveness of the U.S. product would decline compared to Brazil’s,” said Ana Luiza Lodi, an analyst with StoneX Group. “China would then aim to source as much as possible from Brazil, driving up demand and boosting export premiums/basis in Brazil, compared to Chicago.” In a study issued by economists with the National Corn Growers Association and the American Soybeans Association this month, if a hypothetical trade war causes economic damages similar to those seen during the first Trump trade war in 2018, it may cost U.S. farmers billions of dollars.

“As a result of retaliatory tariffs from the onset in summer 2018 through the end of 2019, U.S. agricultural export losses exceeded $27 billion, with China accounting for about 95% of the value lost,” the report said. The NCGA and ASA say that if China – the leading destination for U.S. soybeans and a top destination for corn – cancels its existing waiver on tariffs against U.S. agriculture, then it would cause U.S. soybean exports to China to fall by as much as 16 million tons, or over 50%. Corn exports there would be expected to fall by over 84%, or 2.2 million tons. The losses are even higher if China were to institute new retaliatory tariffs in a renewed trade war. Like with the 2018 trade war, U.S. agriculture is unlikely to find enough new business to cover those losses. “We’ll need to focus on other major markets like Mexico to replace China, but Mexico also comes with risks of renewed trade disruptions under a Trump administration,” said Tanner Ehmke, lead economist covering grains and oilseeds for agricultural lender CoBank. “Mexico, too, would lean harder on South American crops to replace any lost trade with the U.S.”

Mexico is the leading buyer of U.S. corn, and buys far more U.S. corn exports than China. The opposite is true for soybeans – with China purchasing 24.4 million metric tons of soybeans in the 2023/24 marketing year to Mexico’s 4.8 million tons. Higher U.S. tariffs may kickstart efforts from China and South American countries to solidify their trade relationships. This may further crowd out U.S. farmers from world markets, after the previous trade war hurt the perception of reliability of the U.S. as a trade partner, said Krista Swanson, an economist with the NCGA. Brazil has benefited the most from China’s switch in trade partners. Brazil’s agriculture sector has been growing steadily after first producing more soybeans than the U.S. in 2012, according to Department of Agriculture data. The USDA said last year that Brazil will account for nearly 61% of the world market share for soybean exports by 2032. Analysts say that this number could grow larger sooner with the imposition of new tariffs.

“Once land is brought into crop production in Brazil, it will stay in production even after the trade war is over,” said Scott Gerlt, chief economist with the ASA. While a renewed trade war with a second Trump administration will quickly impact China’s appetite for U.S. grains, that appetite may see a decline no matter who wins on Nov. 5, said Arlan Suderman, chief commodities economist for StoneX Group. “Tariffs are certainly a part of the price equation, but the bottom line is that China is moving away from dependency on buying from the United States regardless, due to both geopolitical tensions and price,” Suderman said.