In RealClearPolitics, a provocative thesis, from Vikram Maheshri (U. Houston) and Cliff Winston* (Brookings):

The United States experienced a Great Depression during the 1930s causing one-quarter of its workforce to be unemployed. Although not formally recognized, a growing body of survey evidence indicates that the US has been experiencing a Second Great Depression for decades, worsened by events such as 9/11, the Great Recession, the growth of social media, and the COVID pandemic. However, the causes and consequences of this depression have been largely psychological, not economic, with a notable fraction of the population becoming socially disengaged and depressed.

…

…Trump has made few efforts to address the Second Great Depression. Instead, he has exploited its malaise to win two presidential elections by convincing an important share of the public to vote for him because he gives voice to their fears and anxieties and encourages them to join a movement of like-minded people. Indeed, a closer examination of the links provided above show that the Second Great Depression disproportionately afflicts men and younger and rural Americans—that is, people who form the bedrock of Trump’s political support.

…

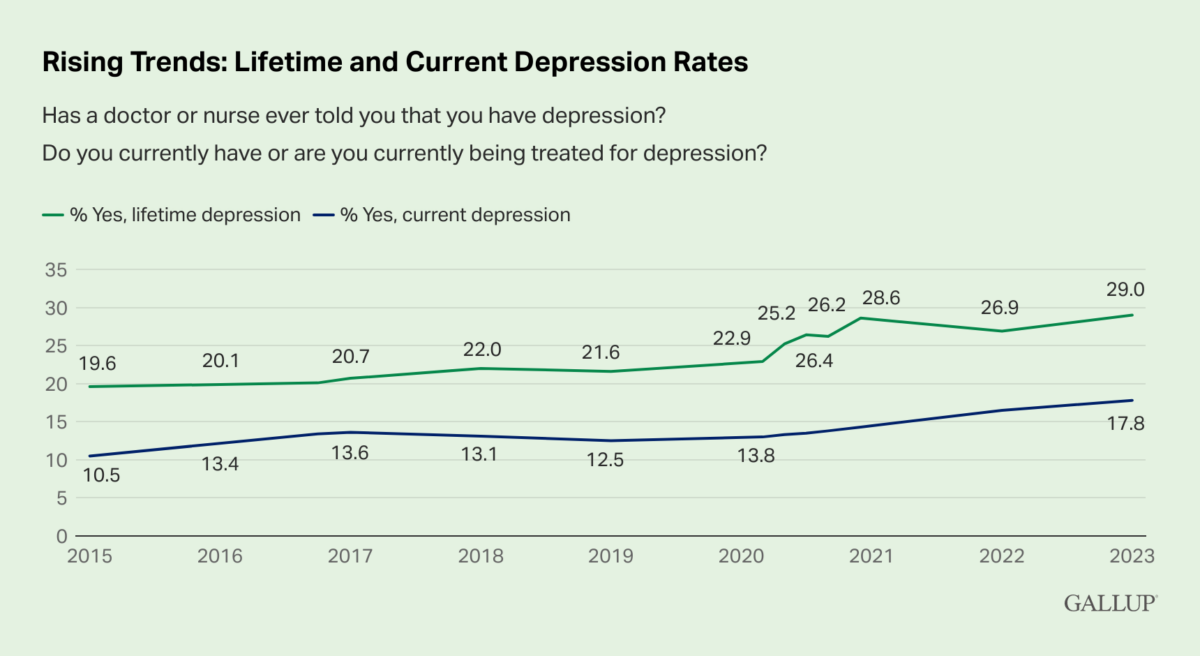

The entire article is here, and does not provide statistical data as this is a difficult thesis to quantitatively and rigorously assess. Clearly, self-reported depression is up, as noted in the article.

Source: Gallup, May 2023.

(*full disclosure: I was Dr. Winston’s RA 40 years ago).

Was Donald Trump’s candidacy more attractive to those who suffered from mental depression? That’s much more difficult to assess, and would require micro data to evaluate.

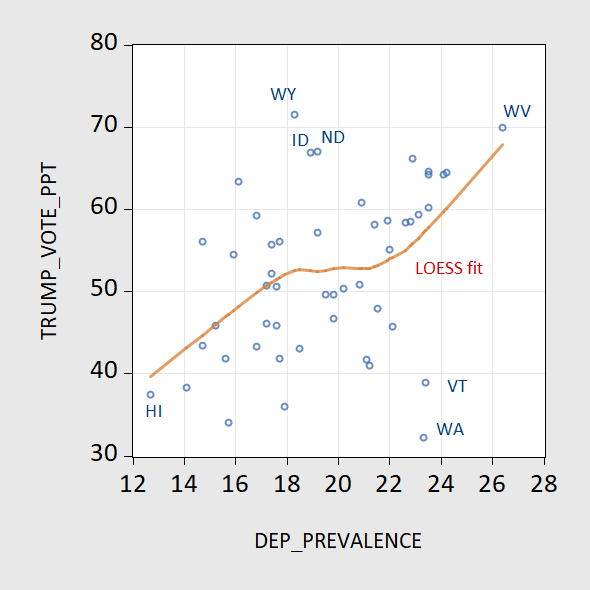

I can evaluate at the state level the following correlation between the prevalence of depression (2020) and voting for Trump in the last election.

Figure 1: Trump vote share (vertical axis) and prevalence of depression (horizontal axis), both in %. LOESS (locally weighted regression fit, 60% window) (red line). Source: NBC, HHS.

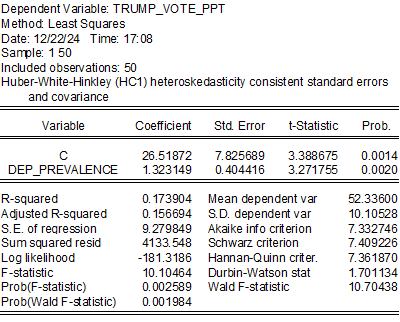

OLS regression results:

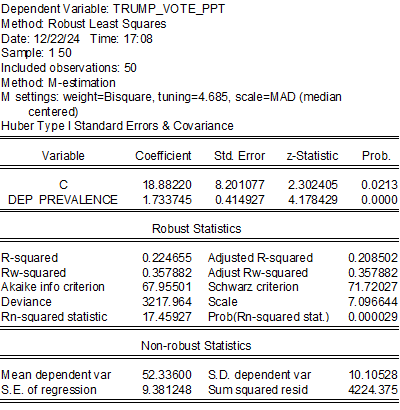

Robust regression results:

The point estimates indicate that each 1 percentage point of increasing prevalence of depression is associated with a between 1.3 to 1.7 percentage point increase in Trump voting share.

Of course, correlation is not causation. And I expect that these are “fragile” regression results in the Leamer sense. However, I was surprised at how much variance was explained by a simple bivariate regression.

One could try to account for the endogeneity of depression prevalence by using 2SLS, but I’ll leave that to others to try. Better yet would be to correlate voting behavior with diagnosis with depression at an individual level. For now, this is an interesting correlation that (I think) buttresses the Maheshri-Winston thesis.

Update, noon CT 12/23:

Peter Ellis has a great post diving further into the statistics, at county level, accounting for the boundedness of shares, and spatial distance.

I don’t think cross-time analysis would be useful here, as depression back in the 60s was considered a personal weakness and failure. The acceptability of mental health diagnoses other than “normal” has increased substantially over the decades. This may be true even today across states – I could see states with more traditional attitudes towards, well, everything, also having more traditional attitudes towards depression and other mental illnesses.

Just to make it explicit, states with “more traditional attitudes” would be, supposedly, the ones where Republicans perform better. So, it would just imply that undercount in those states is bigger. So, correcting such differential level in undercounting would rather magnify x axis, it would be less likely to switch order of the states.

So, while there could be more reasons why there is a relationship shown in the second figure, it is very unlikely to be fueled by differential level of underreporting of depression

In addition to that standard correlation is not causation:

You fit a model predicting vote by depression prevalence, but it doesn’t mean that those with depression vote for Trump. It is also possible that those, who would vote against Trump are unlikely to vote because they are depressed. Well, one point of depression prevalence accounts for more than one vote for Trump, but vote percentage is exactly how people voted and prevalence may be underestimated.

Vasyl: Yup. Both variables are measured with error. Even with Classical measurement error, that’s not innocuous especially on right hand side variable. On left hand side, if not Classical, well I guess that’s one reason to include a constant.

I was pretty sure I’d seen similar results elsewhere, and sure enough:

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2020-53949-001

This study focuses on unhappiness, as defined in a variety of ways. Depression and unhappiness by several definitions suggests a cluster of related, negative emotional states drove Trump’s win. Pew research adds “dissatisfaction with the way things are going” to the cluster:

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/11/13/what-trump-supporters-believe-and-expect/

There is a very strong relationship between education level and presidential preference:

https://www.axios.com/2024/11/07/college-degree-voters-split-harris-trump

That doesn’t necessarily reflect emotional satisfaction, but education is a strong determinant of income, and it turns out, those with the highest and lowest incomes voted more heavily for Harris, while the middle and lower middle voted more for Trump. That’s income by household. Similarly, states with lower average income a very likely to vote Republican, while higher income states vote Democratic.

This is not a contest between explanations. It’s a cluster of overlapping conditions. Income and education go together. Income and depression? People living below the poverty level are twice as likely as others to be depressed:

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db172.htm

The CDC study is not a perfect match with voting patterns, because it doesn’t report depression across all income levels. If there is a progressive improvement as income improves, then there is a match with voting patterns.

Unhappy, dissatisfied, depressed, poorly educated people with middle and lower-middle class incomes vote for Trump. So, populism? The legacy of Faux news? The legacy of neo-liberalism? Yes I think. One cluster of circumstances reflected in another cluster of circumstances, adding up to a felon in the White House. Just like Berlusconi. Just like Netanyahu. Just like Hitler.

*testing

My father was born in 1927, I was born in 1973. My father lived through the Great Depression. German ethnicity. You can do the math on my father’s age when I was born. We got along very intermittently and better towards my father’s last years, when my Dad died in 2012. My Dad said, when he was a child, talk about “space travel to the Moon” was always seen.considered as a comical joke~~Buck Rogers stuff in comic books. I don’t understand why much of this comment section and post deals with the emotions/psychology of depression. As I thought most of the term “Great Depression” only related to the economics implications of the term.

Hey, buddy. Nice to see you back.

Yeah, I noticed the cutie Depression/depression switcheroo, too. The authors are economists reaching out to other social sciences, and we should encourage that, I suppose. I agree with their premise, and have bought into the more general premise that wealth and income inequality are at the root of our political stupidity, so I don’t want to get in their way. I’m not objective.

Don’t be a stranger.

Sitting in bed, reading”WSJ” wonderiing what the Hell I did to piss Menzie off. I’m trying to filter “other thoughts” right this Moment. Watching Bob Ross.

No more error messages when you try to post ?

@ Ivan

If I remember correctly I am getting a 404 error, not the “normal” 405 error. 404 means the server recognizes the comment was sent but is “choosing” not to upload it, which implies my opinions are not generally welcomed by one or both of the hosts.

Today Trump proclaimed: “I will direct the Justice Department to vigorously pursue the death penalty to protect American families and children from violent rapists, murderers, and monsters.”

Uh, wouldn’t that include himself?

This is an interesting, but I think, principally emotional, article.

If we consider a depression as an economic event, then it has to have some statistical foundation. As I have stated before, I consider a depression to be a balance sheet even linked compromised collateral, rather than an income statement event linked to falling revenues or unsustainable expenses, eg, high interest rates.

In a depression, the interest rate mechanism is ineffective because the limits on borrowing are not interest costs, but rather the availability of collateral to underpin loans. You can see this graphically very clearly on this graph from CR (FRED). https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEigDMcLMSZnQFZVnGYLJzqzyRBJ2neOGI9hCijwZ2fQb4qpFn976sktvfDslk9qboIp-t145m6TuwGQoO_kUInPTOrYAx-E5HjhoZI7ZE2xXyApZu___Ymgy60XK8ZyUXXoAso1Fm9Wncwwqa0wF_4uKzS66avscLtBjG0Kw2I0MA2QKI642m1f/s983/Q2MortgageDebt2024.PNG

Note that mortgage debt declines from 2008 to 2015 (with the depression ending in 2016 / 2017 depending on the measure). Thus, the depression in this case is measured from peak to prior peak, not peak to trough. You can see this pattern in all kinds of time series data, for example, VMT or remittances to Mexico.

It should be noted that the depression, in economics terms, does not start in the early 2000s and does not persist beyond 2017 by any measure.

The authors also speak to a kind of societal depression starting in the early 2000s and arguably persisting to the present. I think there is some truth in this, but the narrative, to my mind, seems more complex and multi-faceted. First, I was around in the early 2000s, and there was no depression prior to 2008. Society was largely normal, albeit progressively trying to deal with the incorporation of China into global manufactured goods, financial and labor markets.

The period 2008 to 2016 was the China Depression, as I describe above.

The world saw a decent recovery, albeit a stressed US political scene, from 2017 to early 2020. The pandemic knocked the wind out of all of us, and as Menzie has discussed here, median incomes did not recover 2019 levels until 2024, again depending on the metric. Meanwhile, Russia started a major European war in 2022, and that casts a pall over last three years. There is a constant level of stress and darkness associated with that conflict, and further, a potential world war with China just around the corner. That certainly has a depressive aspect. In that sense, the authors can legitimately claim an extended depressive period in the global economy, but we are really speaking of three discreet and unrelated events: the China Depression, the pandemic and the Russo-Ukrainian war.

Finally, we are seeing ‘colony collapse’ all across the globe, with fertility rates continuing to plummet. This implies either worsening economics for young families — which does seem to be a factor — as well as a loss of hope, a rise in fear, and seemingly greater difficulties in people forming lasting relationships. This is a very big deal, I think, but I do not think we understand it particularly well. Collapsing birth rates do, I think, represent a depressive mindset.

I have some sympathy for the authors, but I think they are mixing our apples and oranges. Their appeal is mostly emotional, rather than technical.