Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Jamel Saadaoui (Université Paris 8-Vincennes). This post is based on the paper of the same title (Aizenman, Ito, Park, Saadaoui, and Uddin, 2025).

1. Introduction

During the past 20 years, the world economy suffered two major crises: the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 (the GFC hereafter) and the pandemic crisis (the COVID-19 hereafter) of 2019-2020. A common denominator between the two crises is that both impacted the entire world rather than just one region or one group of countries. In Aizenman et al. (2025), we analyze the patterns of recessions and recoveries of 101 advanced and developing economies, identifying the turning points of recessions and expansions between 1990 and 2022, and perform cross-country analysis of domestic and external drivers of economic recovery. In addition to the standard independent variables, we include institutional development, political stability, the extent of democracy, and trade restrictions indexes and explore their roles in explaining recessions and recovery patterns.

Two distinct models of economic recessions can be identified. The first, a Hamiltonian recession, is derived from the pioneering work of James Hamilton (Hamilton, 1989) and foresees recessions that prevent economies from returning to their pre-crisis growth trajectory (see Cerra and Saxena (2008)). This type of recession typically leads to a permanent reduction in an economy’s productive capacity and income level. The second model of recession, conceptualized in modern economic discourse by Milton Friedman (Friedman, 1964, 1993), assumes dynamics known as a Friedman-like recession, which is akin to the response of a stretched guitar string. The further the economy is pushed downward, the more forcefully it rebounds.[1] Productive capacity remains largely intact, and the economy does not suffer a permanent loss of income. The supply side remains resilient, in contrast to the Hamiltonian scenario. Countercyclical monetary and fiscal policies may yield very different results in the two models.

To identify economic recessions and recovery, we use the Bry-Boschan (B.B.) algorithm. It automates the cycle-dating procedure in line with the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) tradition (Bry and Boschan, 1971). Using the B.B. algorithm, we identify 419 recessions in our sample of 101 countries over the period 1990-2022. We found that 59 recoveries occurred in 2009 (i.e., the GFC) and 94 occurred in 2020 (i.e., the COVID-19 crisis). Notably, the number of recessions during the COVID-19 crisis is twice as many as during the GFC, illustrating the significant impact of the pandemic. Although many emerging market economies (EME) experienced financial crises in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the number of recessions was not as frequent, suggesting that the crises in emerging market economies were regionally contained.

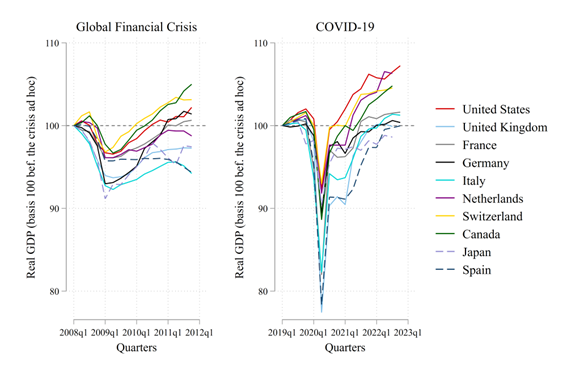

Figure 1. Comparing Two Recoveries: GFC Versus COVID-19 in Industrialized Economies.[2]

Figure 1. Comparing Two Recoveries: GFC Versus COVID-19 in Industrialized Economies.[2]

In Figure 1, GFC seems to have had a longer-lasting impact on this group, with recovery mostly sluggish. For instance, Switzerland and Canada managed to reach their pre-crisis real output level only in the first quarter of 2010. Meanwhile, the peripheral euro-area countries were subsequently hit hard by the euro crisis. On the other hand, the impact of COVID-19 was much bigger than that of the GFC, with Japan and Spain suffering real GDP losses of 20 percent. However, the recovery was also much faster and stronger than during the GFC. The downturn lasted less than two quarters in most cases. For instance, the US and Switzerland managed to recover their pre-crisis real output in the second quarter of 2020. Once again, the recovery was more sluggish for peripheral euro-area countries.

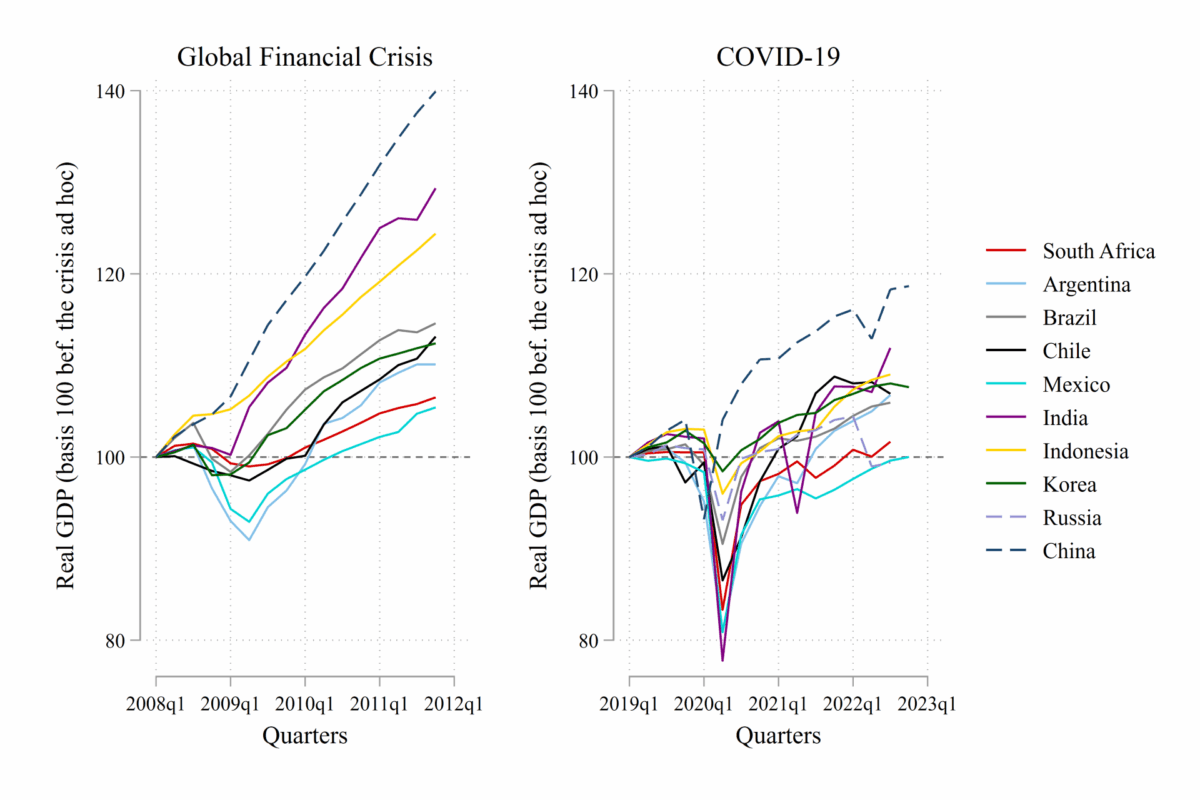

In Figure 2, we compare the two recoveries for a selective group of EMEs. In the left panels, we observe that recoveries after the GFC were faster and stronger in EMEs than in IDCs. Since the GFC primarily affected the financial systems and real economies of financially well-developed advanced economies. In the left panel of Figure 2, we observe that the post-COVID-19 recovery pattern was similar for the broader group of EMEs and IDCs.

Figure 2. Comparing Two Recoveries: GFC versus COVID-19 in Emerging Market Economies.

2. Regression Results

We investigate the determinants of the variables related to recessions and recovery. In addition to the macroeconomic variables identified as important, we include institutional variables based on the principal components (PC) of political risk ratings in the ICRG database.

First, we use panel logit models to estimate the probability of an economy entering a recession.[3]

Then, given the heterogeneity of our sample economies, we obtain insightful results when we apply a panel logit estimation augmented with interaction terms.

Higher levels of holding IR would reduce the probability of a recession, but only for low levels of trade restrictions (i.e., freer trade). This result echoes in the finding of Aizenman, et al. (VoxEU 2023) about the complementarity between the holding of IR and capital account restrictions in the context of terms-of-trade shocks. The buffer effect of IR is only observed when the economy is sufficiently open to trade. When the level of trade restriction is too high, the holding of IR is no longer associated with a reduction of the probability of a recession. When trade restrictions are too high, the buffer effect of macroeconomic variables disappears.

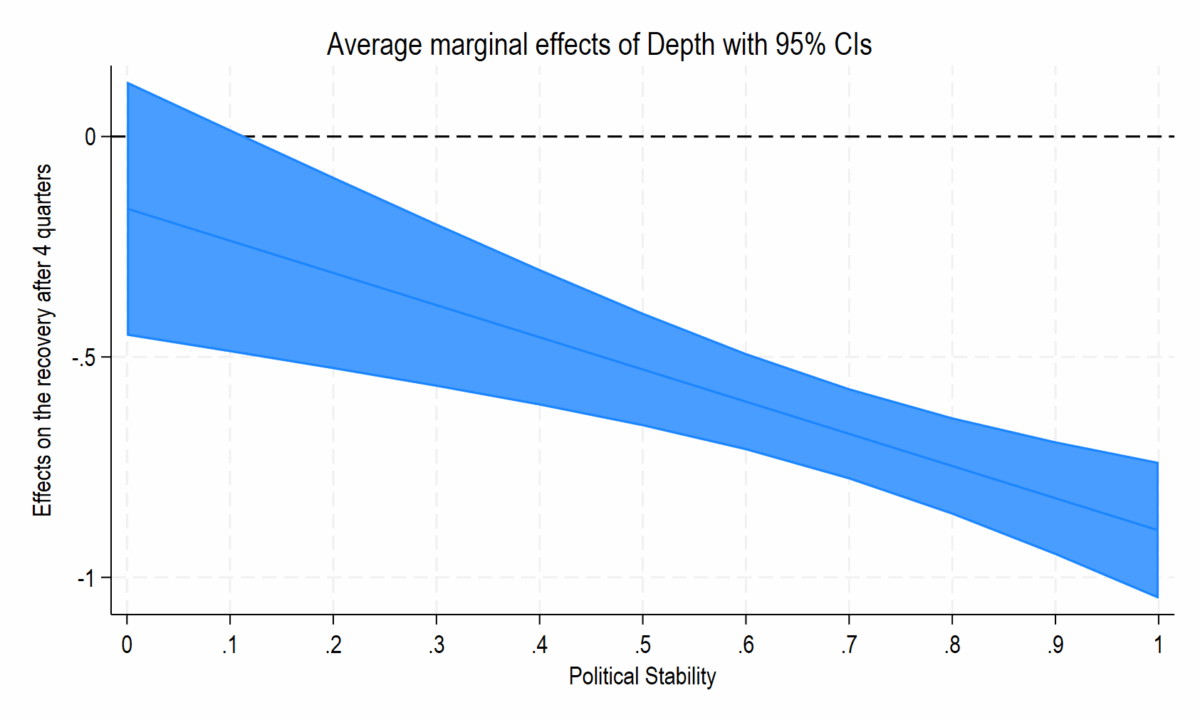

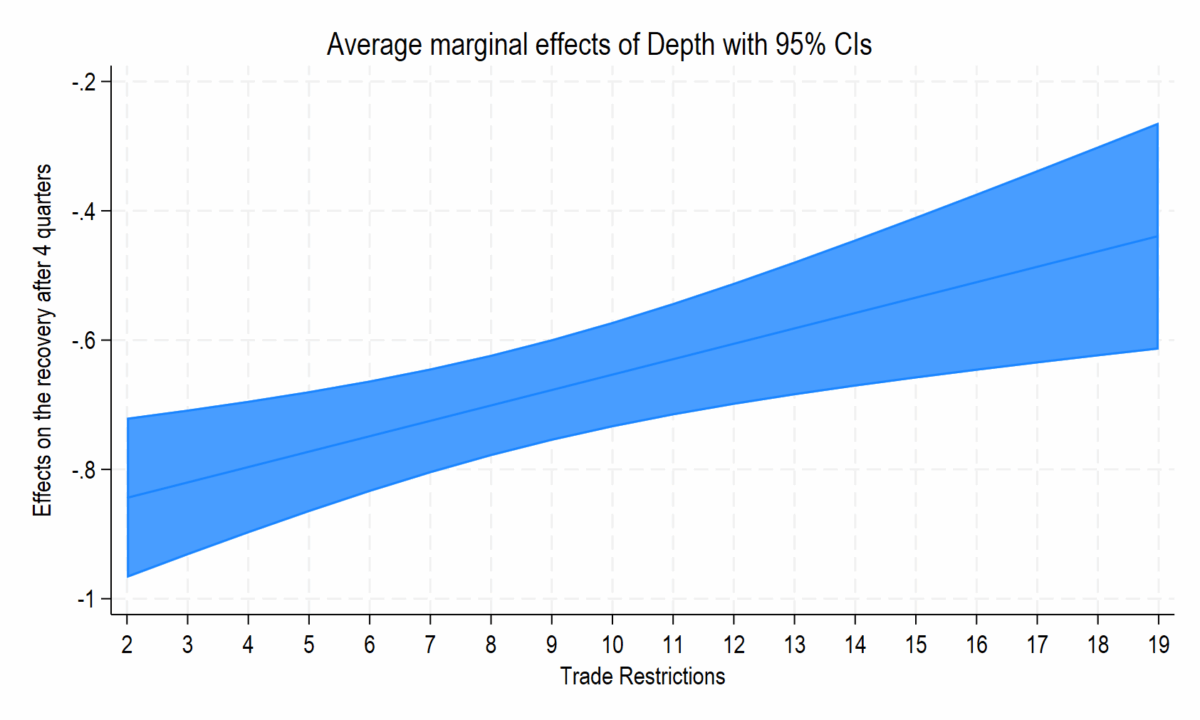

Next, we examine whether Hamilton’s or Friedman’s model better depicts the recovery path in the aftermath of a recession. The results suggest that in a stable political environment (Figure 3), recessions during which the GDP decreases by an additional 1 percent induce a stronger output recovery of around 0.9 percent after 4 quarters. The length of the recession has no significant effects on the extent of the recovery 4 quarters later.[4] When the number of trade restrictions is very low (Figure 4), recessions during which the GDP decreases by an additional 1 percent induce a stronger output recovery of around 0.8 percent after 4 quarters. The length of the recession has no significant effects on the extent of the recovery 4 quarters later.

Figure 3. Deeper recessions, stronger recoveries? Not always due to political instability.

Figure 4. Deeper recessions, stronger recoveries? Not always due to trade restrictions.

3. Summary

We analyze a large sample of industrialized and emerging countries between 1990 and 2022, a period of unprecedented trade and financial globalization. We perform in-depth analysis of the drivers of different patterns of recessions and recoveries, with a focus on the impact of political stability and institutional development. In addition, we empirically explore the role of trade restrictions in economic recovery. We also empirically test the validity of Friedman’s plucking model of the business cycle (Friedman, 1964, 1993). Notably, we provide global empirical evidence that Friedman’s plucking model is less relevant in describing an economy’s recovery path in the presence of political instability, weak institutions, and extensive trade restrictions. Relative to IDCs, EMEs tend to have weaker institutions and more restrictive trade barriers.

References

Aizenman, J., Ho, S. H., Huynh, L. D. T., Saadaoui, J., & Uddin, G. S. (2023). Real exchange rate and international reserves in the era of financial integration. VoxEU. CEPR, 6 Nov. 2023, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/real-exchange-rate-and-international-reserves-era-financial-integration

Aizenman, J., Ito, H., Park, D., Saadaoui, J, & Uddin, G. S. (2025). Global Shocks, Institutional Development, and Trade Restrictions: What Can We Learn from Crises and Recoveries Between 1990 and 2022? (No w33757). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bry, G., & Boschan, C. (1971). Programmed selection of cyclical turning points. In Cyclical analysis of time series: Selected procedures and computer programs (pp. 7-63). NBER.

Cerra, V., & Saxena, S. C. (2008). Growth dynamics: the myth of economic recovery. American Economic Review, 98(1), 439-457.

Estefania-Flores, J., Furceri, D., Hannan, S. A., Ostry, J. D., & Rose, A. K. (2024). A measurement of aggregate trade restrictions and their economic effects. The World Bank Economic Review, lhae033.

Fatás, A. (2019). The 2020 (US) recession. VoxEU. CEPR, 14 Mar 2019. https://cepr.org/voxeu/blogs-and-reviews/2020-us-recession

Fatás, A., (2021). The short-lived high-pressure economy. VoxEU. CEPR, 27 Oct 2021. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/short-lived-high-pressure-economy

Friedman, M. (1964). Monetary studies of the national bureau. The National Bureau Enters Its 45th Year, 44, 7-25.

Friedman, M. (1993). The “plucking model” of business fluctuations revisited. Economic Inquiry, 31(2), 171-177.

Hamilton, J. D. (1989). A new approach to the economic analysis of nonstationary time series and the business cycle. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 357-384.

Kohlscheen, E., Moessner, R., & Rees, D. M. (2024). The shape of business cycles: A cross‐country analysis of Friedman’s plucking theory. Kyklos, 77(2), 351-370.

Notes:

[1] This can be illustrated by the following metaphor: “Like a guitar string, the harder an economy is “plucked down”, the stronger it should come back up” (Kohlscheen, Moessner and Rees, 2023).

[2] The recession data in Figure 1, 2 has been estimated with the Bry-Boschan algorithm to determine the start of the recessions for each country. The real GDP has been recalculated to an index equal to 100 as of 2008q1 for the GFC and as of 2019q1 for the COVID-19 crisis.

[3] To mitigate possible endogeneity concerns, all of the independent variables are lagged for one year. Additional regression results can be found in Aizenman et al. (2025).

[4] Fatàs (VoxEU 2019, VoxEU 2021) shows that the US economy spent too little time close to the potential after the GFC. The race to heal the labor market has been lost due to the occurrence of the next global shock, the COVID-19 pandemic. In his “plucking model with a twist”, the slowness of the expansion matter in determining the next recessions.

This post written by Jamel Saadaoui.

Off topic – Seems like this sex-trafficking thing associated with the felon-in-chief is not going to go away. Seems like maybe the House is in recess for the rest of the summer to avoid examining this:

“…investigators had discovered that four big banks had flagged to the Treasury Department $1.5 billion in potentially suspicious money transfers involving Epstein, much of which appeared to be related to his massive sex-trafficking network.”

https://newrepublic.com/article/198247/trump-epstein-fiasco-ron-wyden

Turns out big banks had not flagged these suspicious transactions until he was arrested. So not only are their crimes involving sex trafficking, but also possibly involving banks’ complicity in sex trafficking, regulatory malfeasance at least.

The bank accounts on the other side of these transactions, over 4,000 of them, apparently belong to clents of Epstein’s sex-trafficking operation, and so collectively represent a “client list”.

By the way, revenues from and properties of any business financed with the proceeds of a crime might be subject to confiscation. I haven’t looked into what has happened to Epstein’s estate, but perhaps other rich criminals were not just clients, but also financiers of Epstein’s sex-trafficking operation. Mighten’t their business revenues and proporties also be subject to confiscation?

The MAGA movement is very much focused on the behavior of our elites. Since Epstein catered to such elites, I expect MAGA-types are going to want to know who was involved; confirmating one’s suspicions is such a joy.

Somebody should look into this.

The problem here is a decades of actively ignoring child molestation effected through transporting unaccompanied minor children….

To pleasure privileged adults, with connections to cover up their crimes.

Who knew what, and when? Who ordered the cover ups?

A help to this fine essay would have been the paper abstract:

https://www.nber.org/papers/w33757

May, 2025

Global Shocks, Institutional Development, and Trade Restrictions: What Can We Learn from Crises and Recoveries Between 1990 and 2022?

By Joshua Aizenman, Hiro Ito, Donghyun Park, Jamel Saadaoui & Gazi Salah Uddin

The Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic were two major shocks to the world economy in the 21st century. In this study, we analyze the patterns of recessions and recoveries of 101 advanced and developing economies. We identify the turning points of recessions and expansions between 1990 and 2022, and perform cross-country analysis of domestic and external drivers of economic recovery. In addition to the standard independent variables, we include institutional development, political stability, the extent of democracy, and trade restrictions indexes, and explore their roles in explaining recessions and recovery patterns. For the whole sample, we find that deeper recessions are followed by stronger recoveries, in line with Friedman’s plucking model of the business cycle. However, the empirical evidence for the plucking model becomes weaker if institutional development is limited and trade restrictions are high. We show that recessions that create conflict and trade tensions differ sharply from those that do not, a highly relevant finding in the current global climate of heightened trade tensions and geopolitical uncertainty. Finally, since developing countries tend to have weaker institutions and higher trade barriers, our evidence suggests that if policy-makers seek to cushion global shocks, they will need to rely on countercyclical monetary and fiscal policy. Implementation of such policies is generally facilitated by robust and credible monetary and fiscal policy frameworks.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1KRO4

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for China, Korea, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, 1992-2023

(Percent change)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1KROr

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for China, Korea, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, 1992-2023

(Indexed to 1992)

The China Cheerleader is back. Just remember, China’s growth depends partly on slave labor. ltr has never objected to the enslavement of Uighurs.