Oral arguments before the appellate court take place this week. Suppose the tariffs invoked under IEEPA are struck down, then that decision would likely be appealed to the Supreme Court (eventually). From CNBC:

The case, known as V.O.S. Selections v. Trump, is the furthest along of more than half a dozen federal lawsuits challenging Trump’s use of the emergency-powers law.

It’s set for oral argument before the Federal Circuit on Thursday morning.

“I think the tariffs are at risk,” said Ted Murphy, partner and head of global trade practice at law firm Sidley Austin, in an interview with CNBC.

The law has “never been used for this purpose,” and it’s “being used quite broadly,” Murphy said. “So I think there are legitimate questions.”

What about at the Supreme Court? The article continues:

“Trump will probably continue to lose in the lower courts, and we believe the Supreme Court is highly unlikely to rule in his favor,” U.S. policy analysts from Piper Sandler wrote in a research note Friday morning.

The analysts wrote that such a loss would effectively mean the collapse of almost every trade development that Trump has held up as an accomplishment during his first six months in office.

“If the Supreme Court rules against Trump, all of the trade deals Trump has reached in recent weeks — and those he will reach in the coming days — are illegal,” the analysts wrote.

“So are his letters informing countries of their new tariffs, the current 10% minimum, and the reciprocal tariffs he has proposed or threatened,” they added.

If the analyst is correct, then the question would be whether Mr. Trump complies. Abolishing the tariffs would then mean a massive hit on the US and global economy would have been for naught, while elevating policy uncertainty to capital investment-reducing levels. (Of course, better to get rid of the tariffs than to keep them.)

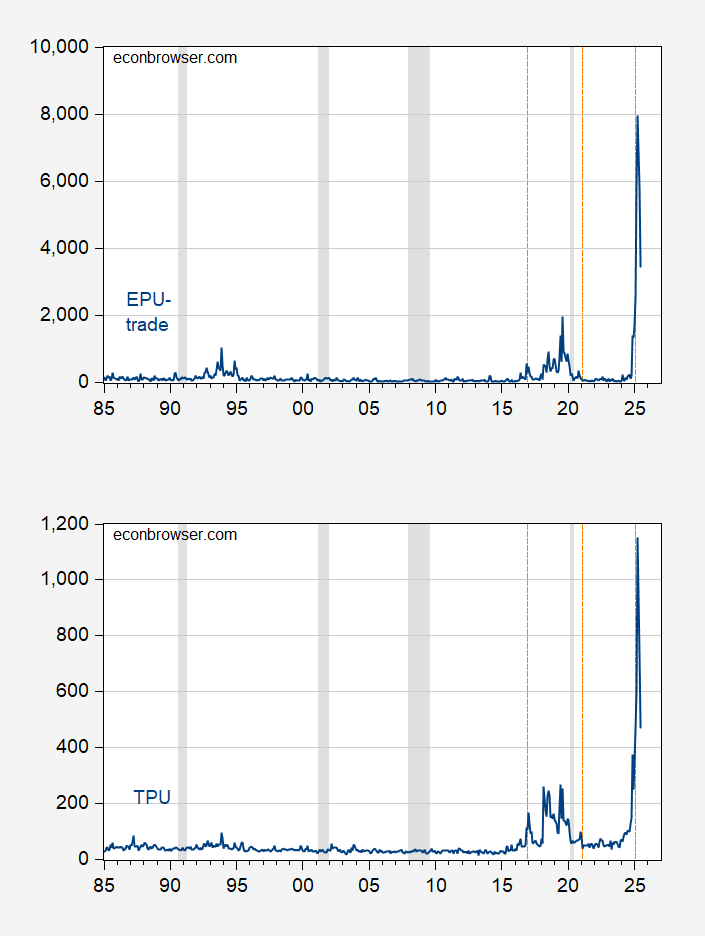

Figure 1: Top Panel: EPU-Trade, Bottom Panel: EPU. NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: policyuncertainty.com, Iacoviello, NBER.

More on the cases from the CRS.

By the way, I’m not certain what “national emergency” we’re in. GDP, core GDP are growing, inflation is for the moment below 3% (albeit accelerating), unemployment is at 4.1%.

The question the analyst probably has in mind is whether tariffs can be imposed without congressional approval. The threat of tariffs is not illegal. Negotiating trade deals is not illegal. Imposing tariffs? Unless specific legislative authority has been granted, the president has either very limited or no right to impose tariffs under the Constitution.

The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934 was the first legislation which allowed presidents to negotiate tariffs generally without specific approval for each negotiation. Congress still has to approve. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 allows presidents to impose tariffs to protect national security. A finding of a threat to national security is required, and not just the assertion of a threat by the president. There has been no such finding against Canada, Mexico, the EU, Japan… Maybe previous findings against China, Russia, North Korea and some Talib

The legality of the felon-in-chief’s tariffs almost certainly has to do with Constitutional authority and delegation of that authority. Until the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, presidents needed specific authority from Congress even to enter into trade negotiations. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 allows presidents to impose tariffs if imports threaten national security, but only after a process involving investigation and specific findings of harm. The Trade Act of 1974 provided “fast track” negotiating authority (mostly a ban on Senate filibusters of ratification), but no authority to avoid ratification. Sections 201 and 302 of the 1974 Act also allowed tariffs to address specific harms to the U.S. economy, but again, only after a demonstration of those harms. Unsupported presidential opinion isn’t enough to invoke Sections 201 or 301.

The one legal claim the felon can make falls under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (50 U.S. Code, Chapter 35). This is where a declaration of emergency comes in – under the IEEPA, an emergency declaration is used to justify presidential action, pretty obviously what the felon’s advisors have told him. However:

“The President, in every possible instance, shall consult with the Congress before exercising any of the authorities granted by this chapter and shall consult regularly with the Congress so long as such authorities are exercised.”

I don’t recall any such consultation.

In J. W. Hampton, Jr., & Co. vs the U.S. (1928),the Court found that an “intelligible principle” must underlie any delegation of Congressional power to the president. “I’m the freakin’ president!” doesn’t meet that standard, so we’re likely to hear some pretty fancy claims about intelligibility in the next few days. We’re really looking at an unconstitutional exercise of power; “No kings” and all that.

Now, we know our current Justices don’t have much use for Supreme Court precedent, but in United States v. Belmont (1937), the Court made clear that presidents’ latitude for action independent of Congress is limited and bound by existing law.

There has been no legitimate effort to find that national security is under threat from trade, merely a declaration of a “national economic emergency” by the felon-in-chief, with no Congressional consultation and no evidence presented. Not even an effort to define this emergency, or emergencies in general. “Emergency” is also rather at odds with “so much winning!”, not that public expressions of personal vanity are likely to carry much weight with the Court. If we soon find ourselves in a recession – next best thing to an “emergency” – it’s likely to be the result of the felon’s own unconstitutional actions. Kinda like back in 2019, when we might have been drifting toward recession, most likely because of the felon’s first-term trade policies.

What’s next? Good question. Not that I think other nations’ leaders are vane or stupid enough to behave like the felon, but what happens if the Court overrules the felon? Might other governments look at this mess, find the U.S. unreliable, and take actions of their own. Mightn’t powerful domestic interests begin agitating for tariff protections in other countries? Where is the global trade system headed after the Court has its say?