Bill McBride’s assessment here.

In early April, I went on recession watch, but I’m still not yet predicting a recession for several reasons: the U.S. economy is very resilient and was on solid footing at the beginning of the year, and perhaps the tariffs are not enough to topple the economy.

In the short term, it is mostly trade policy that will negatively impact the economy. However, there other aspects of policy that bear watching – especially immigration.

Yesterday, Mark Zandi was stating his case for being wary:

Moody’s Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi said the U.S. economy is “on the precipice of recession,” citing indicators from last week’s economic data releases.

In a social media post Monday, Zandi pointed to stagnant consumer spending, contracting construction and manufacturing sectors and projected employment declines.

Rising inflation makes it difficult for the Federal Reserve to provide economic stimulus, the economist said

While unemployment remains low, Zandi attributed this to declining labor force growth rather than economic strength.

“The foreign-born workforce is shrinking and labor force participation” is falling, he wrote.

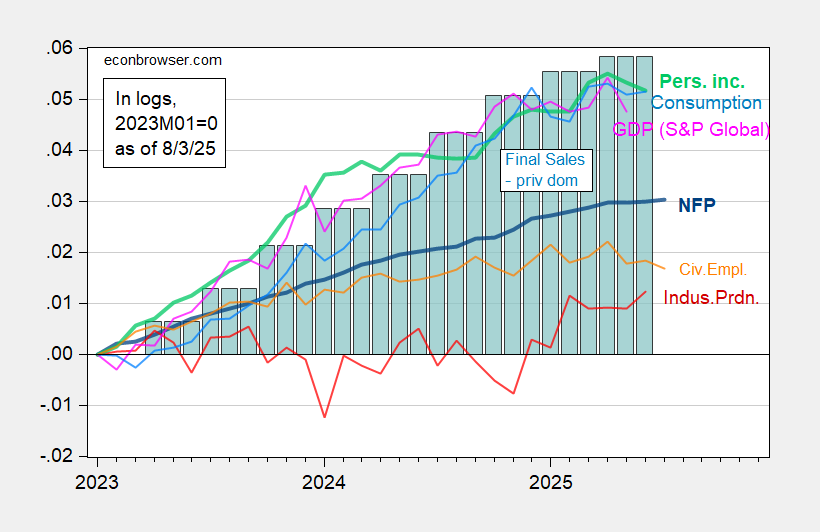

Here’s my picture of the state of the economy, with series not restricted to NBER BCDC’s key indicators, and substituting in final sales to private domestic purchasers for GDP:

Figure 1: Nonfarm payroll employment (bold blue), personal income excluding current transfers (bold light green), civilian employment, experimental series with smoothed population controls (orange), industrial production (red), S&P Global monthly GDP (pink), and final sales to private domestic purchasers (teal bars), all in logs 2023M01=0.

Personal income, consumption, civilian employment, and monthly GDP are all below recent peaks. Industrial production is up, but nonfarm payroll employment is essentially flat over the last three months (33K/mo). NBER BCDC places highest emphasis on employment (presumably NFP) and personal income.

Because the Sahm rule hasn’t been triggered and nonfarm payroll employment continues to rise, I — like CR — don’t think the downturn has arrived as of July (recalling we’re in August, and all the July numbers will be revised).

Addendum:

Goldman Sachs today:

US growth: nearing stall speed

Friday’s payrolls report reinforced our view that US growth is running below potential and near stall speed—a pace below which the labor market weakens in a self-reinforcing fashion. While the unemployment rate rose only modestly in July (to 4.25%), we estimate that the pace of underlying job growth plummeted to 28k (from 206k in Q1), reflecting weakness in the July survey data as well as a surprisingly sharp downward revision to May and June payroll growth that constituted the largest two-month revision since 1968 outside of recession. Looking ahead, we expect growth to slow a touch further in H2 to roughly 1% (from 1.2% in H1) for full-year GDP growth of 1.1% (Q4/Q4), reflecting continued weakness in consumer spending as well as declines in business investment, residential investment, and government spending. We think this should set the scene for Fed easing and continue to expect three consecutive 25bp rate cuts in September, October, and December followed by two more cuts in 1H26. This should support a further rally in US front-end rates as well as substantial further Dollar depreciation, consistent with our bias to be long US rates and short the Dollar, as we see room for the market to price a more dovish Fed.

Another sign of a weakening in the economy is labor market conditions. Here’s a comparison of nominal wages growth between job switchers and stayers:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1Lb2g

After a period of sizable gains for switchers, they are now getting smaller pay gains than those who stay. Both series, meanwhile, are showing smaller gains than in the 2022-2024 period.

It looks like job switchers are no longer switching for a positive reason – for more money. The implication is that workers are now switching when compelled to do so by something less positive, like bad working conditions or because the household is relocating.

Here is a picture of job quits vs wage gains:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1Lb4z

Both are down; when wage gains are smaller, quitting doesn’t pay, so don’t bother.

Here’s the 12-month average wage gain against the jobless rate:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1Lb2K

The story there is pretty obvious. Keep in mind that we’re looking at nominal wage gains.

Wage gains, wage differentials for changing jobs, the unemployment rate all tell the same story – the labor market is squishy. Firing the BLS Commissioner won’t change that.

Bill McBride follows housing in somewhat different fashion than I do.

In particular, his favorite metric of new single family home sales, while very leading, is very noisy and heavily revised, which is why I prefer single family permits. They have a much better signal to noise ratio and are almost as leading.

Further, rather than focus simply on how much sales have to go down before a recession – 20%, which was much more than they went down in 2001 and much less than they went down in 2007; I focus on the *order* in which the leading metrics go down. To wit, single family permits almost always peak first, followed by housing units under construction, followed by residential construction employment and new homes for sale. Recessions typically only happen after *all 4* have turned down.

Here’s what the last 5 years look like:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1Lbab

Single family permits peaked in 2021. Units under construction did not peak until October 2022. The average (with considerable variance) units under construction have gone down before a recession is about 15%. We’re down about 20% now. Residential construction employment probably peaked in March, although it is only down -0.2%. And new homes for sale have not turned down yet. Another reason I am on “recession watch” but not a warning – yet.

“recalling we’re in August, and all the July numbers will be revised”

Will they? Now that Trump has fired the head of BLS?