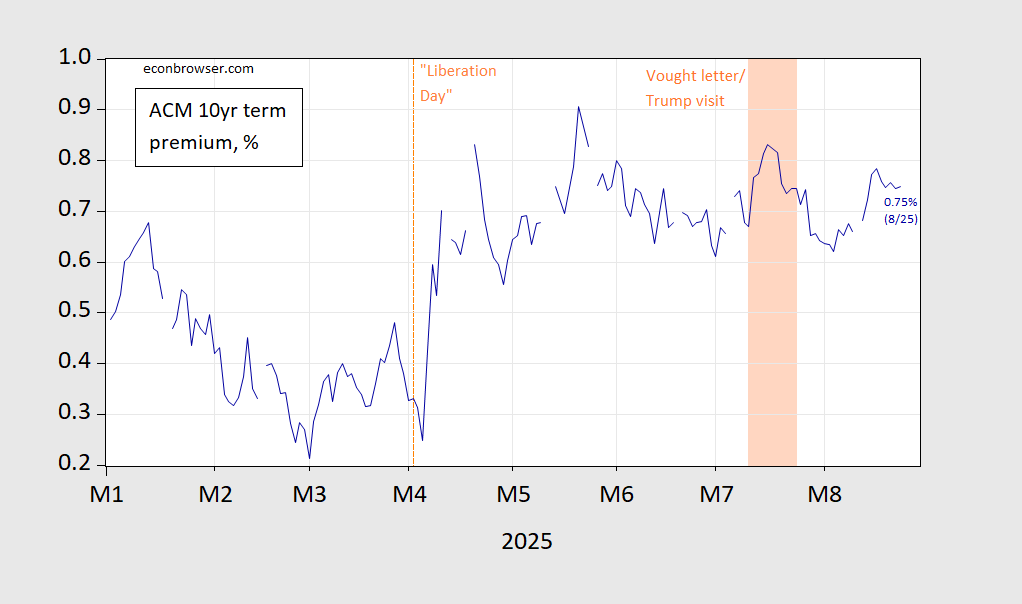

That’s Jared Bernstein’s advice, in the wake of Trump’s escalation of the war on Fed independence. Here’s the picture up to yesterday before the letter to Cook, using the NY Fed’s (Adrian, Crump and Moench) model:

Figure 1: Ten year term premium, in % (blue). Light orange shading denotes period between Vought letter to Powell and Trump’s visit to Fed. Source: NY Fed.

Professor Chinn,

Looking at the NY Fed Excel file, I think you mean to show a date of 8/25 above and not 7/25.

AS: Yup! Thanks, corrected.

Some broad strokes regarding the relationship between term premium and interest rates. Term premium trends with the funds rate, long term:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1LOMn

I can’t get FRED to show the expected path of the funds rate, but there’s some evidence term premium responds to changes is Fed policy expectations.

Term premium also trends, somewhat less obviously, with inflation expectations:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1LONB

And inflation expectations, of course, vary with actual inflation, but with a policy anchor:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1LOOo

The policy anchor was established over the years, starting with Volcker. Absent the anchor, inflation expectations become more variable, as well as higher. Since term premium trends with inflation expectations and fed funds, we are presented with a conundrum if the funds rate and inflation expectations become less tied to one another, which is to say, if the Fed becomes more politicized.

If term premium is what investors have to be paid to take on risk over the life of the security, then expected inflation should dictate term premium, because higher inflation is also more variable and less predictable; investors absorb more risk when uncertainty is higher. In fact, lower and more predictable inflation allows for a lower and more predictable fed funds rate, which helps account for term premium and the funds rate trending together.

That’s why Bernstein advises watching term premium. Less certainty about the inflation outlook, and by extension about the outlook for the cost of funding, would show up as higher term premium.

One last thing – which term premium should we watch? Here’s a look at 1, 2, 5 and ten-year premia:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1LOSq

Notice that 1,2 and three-year premia are headed lower, while the premium at ten years is not. That might be because shorter maturities are more anchored to the near-term funds rate. If so, then we get a cleaner look at inflation uncertainty with longer-maturity term premia.

It might also reflect concern over fiscal policy. The felon-in-chief may not gain control over the Fed, but the Big, Bloated Budget Bill is already the law of the land. And the fiscal mess created by that bill worsens with the passage of time.

Seems that even Marketplace radio has caught on to the risk that long rates could rise in response to the Fed cutting rates in response to political demands:

https://www.marketplace.org/story/2025/08/26/heres-why-trumps-attempt-to-influence-the-fed-could-backfire

A central point in the argument that piticizing the Fed could lead to higher long rates is that the Fed only controls short rates, while private actors control long rates. Well…maybe.

A point I have not read yet in the expanding press coverage of bullying the is that the Fed does sometimes dabble in long rates. The Fed is currently engaged in shedding assets, though probably not for much longer. If the felon-in-chief had any real understanding of how the Fed influences market rates, he’d be howling about that, too. It would provide an entertaining test of GOP principles, since Republicans have generally been opposed to Fed asser purchases and encouraged shrinking the balance sheet.

Anyhow, a sufficiently politicized Fed could simply monetize Treasury debt in true “fiscal dominance” fashion. That would very likely lower Treasury rates, but not necessarily private borrowing rates. Certainly wouldn’t lower inflation.

Authoritarianism, debt monetization and inflation – how very Argentina.