Yesterday, in a speech before the Economic Club of New York, Fed Governor Stephen Miran, on leave from the White House CEA, spoke on “Nonmonetary Forces and Appropriate Monetary Policy.” I was confused.

As Jonathan Levin points out today in Bloomberg Opinion, pre-CEA Stephen Miran had argued that r* had risen, while Fed governor Stephen Miran argues it has fallen. Hmmm. But this was not my point of confusion. Really, it was this section of his speech, where he argued that higher tariff revenue (against the backdrop of an unmentioned income tax revenue cut) would mean a lower r* that caught by attention.

Policies Affecting r*

Population growth…

Increases in national saving from trade policy

Additionally, trade renegotiation and the tax legislation recently passed by the Congress should also affect r*. I think of this primarily through the increase in national saving—that is, the net supply of loanable funds.

With respect to tariffs, relatively small changes in some goods prices have led to what I view as unreasonable levels of concern. While my read of the elasticities and incidence theory is that exporting nations will have to lower their selling prices, I also believe tariffs will lead to substantial swings in net national saving.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates tariff revenue could reduce the federal budget deficit by over $380 billion per year over the coming decade.10 This is a significant swing in the supply–demand balance for loanable funds, as national borrowing declines by a comparable amount. A 1 percentage point change in the deficit-to-GDP (gross domestic product) ratio moves r* by nearly four tenths of a percentage point, according to the average of estimates summarized by Rachel and Summers.11 This 1.3 percent of GDP change in national saving reduces the neutral rate by half a percentage point.12

Tariffs are not the only means by which trade policy is affecting the supply of loanable funds. Loans and loan guarantees pledged by East Asian countries in exchange for relatively low tariff ceilings have reached $900 billion.13 These guarantees entail an exogenous increase in credit supply, which research suggests would be around 7 percent.14 Using Council of Economic Advisers’ (CEA) estimates of the interest elasticity of investment and Michael Boskin’s interest elasticity of saving, this would further reduce neutral policy rates by around two tenths of a percentage point.15

Increases in national saving from tax policy

The large tax law passed this year also has a strong effect on national saving.16 There are, of course, other consequences of the tax law besides the increase in net national saving, which I’ll discuss later in the context of the output gap.The CEA calculates an increase in national saving of $3.83 trillion over the next 10 years (relative to the previous policy baseline), resulting from economic growth induced by tax policy.17 This represents roughly 1.3 percent of GDP, implying a half of a percentage point reduction in r* and the appropriate policy rate through the Rachel–Summers channel.Indeed, the federal deficit in the second and third fiscal quarters of this year was nearly $140 billion less than in the comparable period last year. This is a small sample size but indicative, in my opinion, of the direction of the deficit.

On the other hand, the CEA estimates that the tax law will generate annual investment increases of up to 10 percent in the next several years relative to the previous policy baseline. This should be associated with an increase in r*, and thus the appropriate fed funds rate, of around three tenths of a point. Let me also note that while I am relying partially on previous CEA research at the moment, I look forward to working more with Board staff and their forecasts in the coming months.

Effect of deregulation and energy on r*

…

Well, first tariff revenue is bounded by the fact that import quantities respond to tariffs, so yes, tariff revenues are up. But this can’t make up for anywhere near the hole blown in the Federal budget by the OBBBA. So, if he’s talking about net movements in r*, he would if he were an honest analyst mention the fact that r* has likely risen.

As for the dynamic estimates of tax revenue increases due to OBBBA and Trump deregulation, Miran citing his own groups assessment is understandable, but also delusional as something to cite.

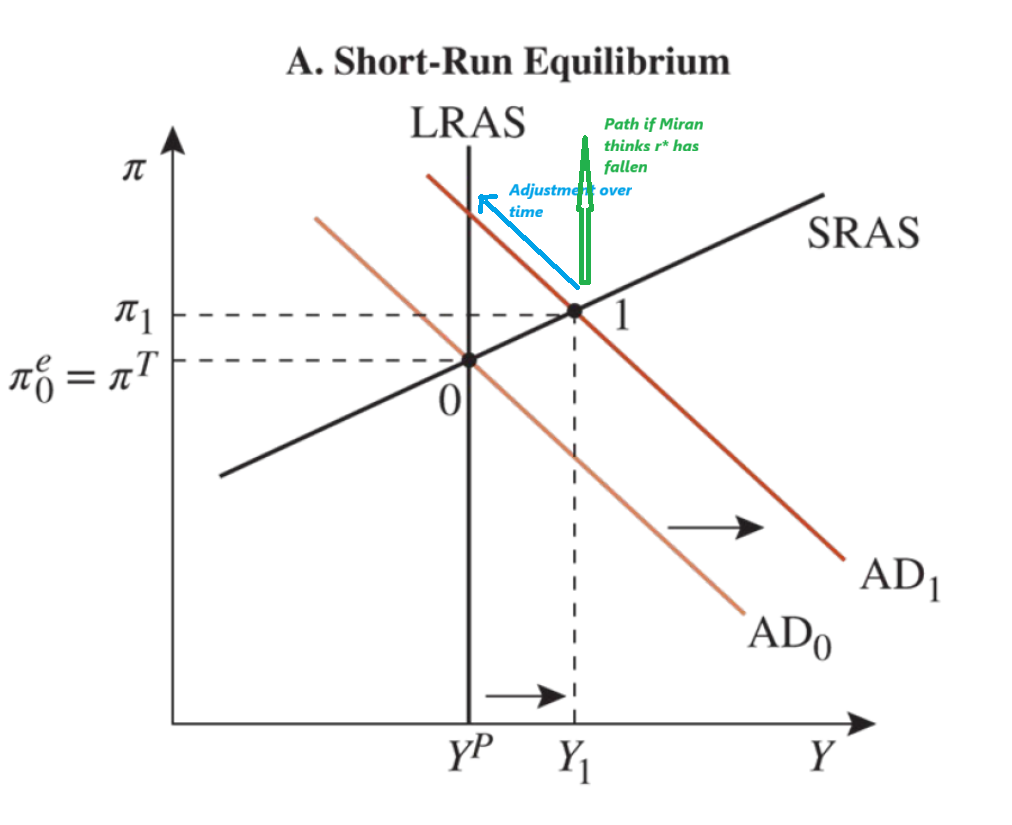

So, say r* has risen (rather than fallen as Miran argues); then to push for lowering interest rates means Miran has to be implicitly arguing for a higher target inflation rate, πT. Any ol’ New Keynesian model with a money reaction function and a Phillips curve will get you that. (For a quick refresher, look at this derivation I compiled for my students, based on the Cecchetti-Schoenholtz exposition).

Source: Cecchetti-Schoenholtz Chapter 22, as modified by Chinn.

What you said. Also:

“While my read of the elasticities and incidence theory is that exporting nations will have to lower their selling prices, I also believe tariffs will lead to substantial swings in net national saving.”

In plain English, he’s saying our trade partners will pay the tariffs. The rest is just specialist language meant to keep the common folk from mocking this glib, self-serving stuff. All the more reason for specialists to mock him.

Miran’s “reading” ought not be weighed as heavily as the views of a specialist in international finance (our host) or a Nobel-Prize-winning trade theorist (Krugman) or the consensus view of the economics profession. The unbiased assumption ought to be that the felon-in-chief’s hired help is wrong whenever he disagrees with his betters.

Loanable funds? Clearly, Miran hasn’t cracked an economics text in quite some time:

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/working-paper/2015/banks-are-not-intermediaries-of-loanable-funds-and-why-this-matters

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40888-022-00286-4

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46464647_On_Keynes's_Criticism_of_the_Loanable_Funds_Theory

Miran is basing his r* claims on a long-outmoded theory of banking. Not only is it outmoded, but as these papers note, modern financial theories of banking fit the data better than does the loanable funds theory. Miran is arguing about real-world outcomes from a theory which is a poor match for real-world outcomes.

As Menzie noted, Miran’s effort to back r* out of an estimate of future GDP growth is delusional. The estimate of growth Miran uses, like his claims about who pays tariff, is something he made up. You can’t back out Miran’s r* estimate from mainstream GDP estimates.

And, by the way, if one looks back at the writings of respected economists in policy-making roles, you’ll find they often overtly choose outside growth estimates as a starting point for analysis, thus avoiding the implication of bias. Miran has chosen his own estimate of growth as his starting point, when other conventional estimates would not give him the result he wants. Might as well just have the felon-in-chief write the speech.

This is the same quality of work as Miran’s audition document, when he argued for tariffs, taxes on foreign purchases of Treasuries, beating up our trade partners diplomatically. None of it was adequately justified, but Miran used all the “I know stuff” language anyone could possibly want; Miran’s is a much higher-class grift than little Antoni’s, but the economics is just as bad.

Trade partners??? Please. Its a attack on US business. Foreign purchases of US treasuries are basically bowing to the king. Miron wants a one world dictatorship.

There is nothing to be confused about. Just listen to our leaders speech at the UN yesterday, and the thought process will be clear.

It seems to me this guy is using economic jargon to try and show an economic argument that has no legs