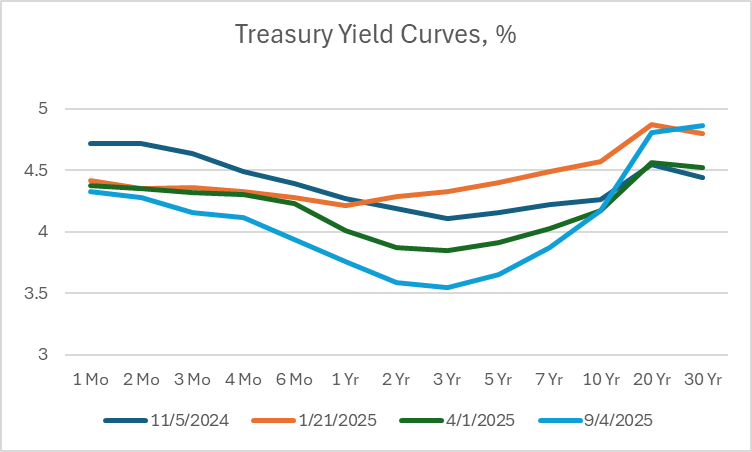

The yield curve at the short end is almost as inverted as it was in November 2024. In fact, it’s more inverted than on January 21st, 2025, the day after Trump’s inauguration. Yet, at the long end of the spectrum, 30 year yields are back up to January 21st levels.

Figure 1: Yields on 11/5 (dark blue), on 1/21/2025 (orange), 4/1/2025 (green), 9/4/2025 (light blue), in %.

The downward movement since January over the 1mo to 3 yr portion of the spectrum indicates that future rates are likely to be lower than imagined at the beginning of Trump’s term. Since rates drop in the 6 month to 1 year onward portion since April 1st, at least some of this is due to the tariff-induced growth drag.

The long end (30 years) is consistent with either of three interpretations: (1) belief in unrestrained deficit spending is pushing up real rates, (2) belief a browbeaten Fed will monetize, or (3) sovereign default risk has risen.

Either, or all in some combination.

Could you elaborate on why “ belief a browbeaten Fed will monetize” would push long rates higher? I can imagine why perceptions of institutional weakness at the Fed could push long rates higher but I don’t follow why monetizing does it—is your point that the Fed’s (hypothetical) monetizing would be such a strong signal of institutional weakness it would overwhelm the effect of increasing demand for long term debt?

Monetizing debt does at least two things which could boost long-term interest rates. First, it could increase the inflation premium. Second, it could lead Congressional budgeteers to run larger deficits than would otherwise be the case.

Generally speaking, inflation is the largest source of variability in long-term U.S. Treasury yields, followed by economic performance, with the deficit bringing up the rear. The experience in other countries is that as deficits rise, the importance of deficits in determining long-term interest rates increases.

Ok, I agree in principle. But there’s a big stretch from possibly raising inflation premia or encouraging Congress to spend more to overcoming the first order effects of increased demand lowering rates.

Shaptse: If the Fed lowers the policy rate (Fed funds rate) relative to what it otherwise would have been, then ceteris paribus, the money stock must be increased relative to what it otherwise would have been. Faster money supply growth eventually shows up in faster inflation; using the Fisher relation, then, the nominal interest rate will rise. That much is textbook. If long term bonds are imperfect substitutes for short term, and long maturity bond valuations are more sensitive to interest and inflation changes, then the risk premium will increase. Both of these raise the nominal interest rate (what happens to real rates is a different matter).

may want to update that chart after the 10 year move today. why is the 10 year dropping if, as trump claims, we have the strongest economy ever? rates dropping within an inflationary environment could be a very dangerous sign.