In a recent Economist article, Gita Gopinath considered the implications of a AI bust similar in magnitude to the 2001 dotcom bust for the global economy.

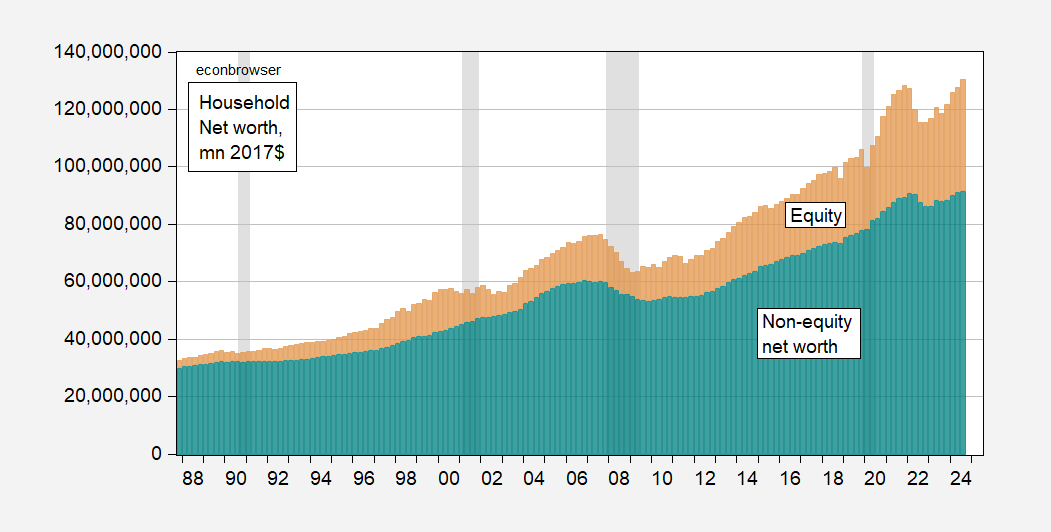

I thought I would consider a more narrow question of a what happens to US household wealth. Consider household equity and mutual fund wealth as a component of net worth.

Figure 1: Household net worth ex-equity+mutual funds (teal bar), household holdings of equity+mutual funds, mn. 2017$. Deflated by PCE deflator. NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: Federal Reserve Flow of Funds, and BEA via FRED, NBER, author’s calculations.

Mid-2025 household wealth in equities and mutual funds is approximately $51 trillion. A 26% drop in capitalization — as took place 2000Q4-2001Q4 — would reduce that by $13.3 trillion (all ballpark figures). (Gopinath’s calculation was likely based on total capitalization, including stocks held by rest-of-the-world).

If the sensitivity of consumption to wealth is 5 cents on the dollar, then that translates to a reduction of some Ch.17$ 526 billion, or about 3% of mid-2025 consumption, distributed over several years. Using a sensitivity of 3 cents on the dollar (might be more appropriate for equity wealth), then a reduction of about 1.9% is implied.

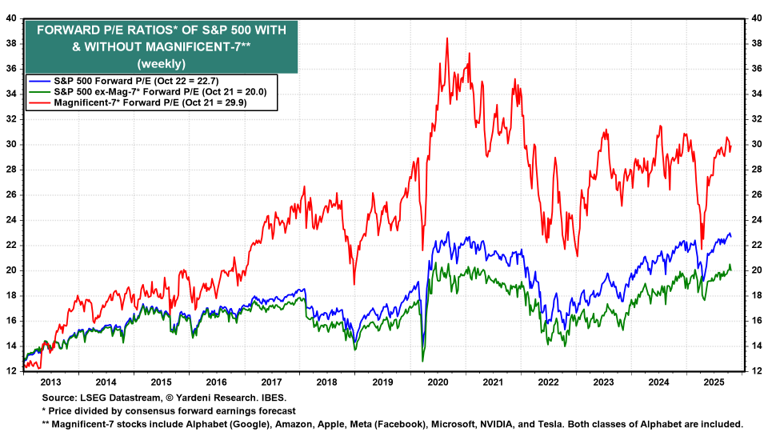

For reference, here are the forward P/E ratios for the Magnificent 7 and the S&P500, including and excluding the Magnificent 7:

Source: Yardeni.com.

The Buffet Indicator may be of interest.

https://currentmarketvaluation.com/models/buffett-indicator.php

Nice.

Notice the upward bias over the entire history – there has never been a 2-standard-deviation reading to the downside, while we have had three periods of 2 SD readings to the upside, including now.

A couple of things come to mind. One is that if a larger share of GDP is produced by publicly-help firms, that would cause a rise in the ratio over time. Another is that reduced volatility in output and thus in earnings – reduced risk – could justify higher valuations.

I don’t know if either of these is actually the case. The fact of increased industry concentration makes me think the first one is true, but it’s late and I’m not gonna find out right now.

That 1.9% decline in household consumption amounts to about 1.3% of GDP. That’s the first-round effect. Production would fall in response to the fall in demand. Hiring would fall. Despite a likely decline in interest rates, credit conditions would tighten. And so on. Those knock-on effects would cause a drop greater than 1.3% of GDP.

Policy would have some effect. Most obvious is the fiscal response; if Congress opens the spending tap, that would offset some of yhe drop in private demand. The House is busy avoiding the release of the Epstein files and Congress can’t pass a budget, and the deficit is already pretty big. Big spending bill from these guys? Trade typically has a counter-cyclical effect, imposing some of the domestic demand loss on foreign producers during rrcession. But, tariffs, ya know, so the effect in this cycle would probably depend on timing. If imports are already depressed due to tariffs, there’d be less room for additional reduction. With other countries imposing reciprocal tariffs on our exports, there’d be less chance to shore up domestic production with exports. Heaven knows how the dollar would fit in.

Jared Bernstein is arguing that heavy reliance on higher-income households in the performance of aggregate consumptiin means that the wealth effect may be more potent on the downside than is normally the case:

https://econjared.substack.com/p/whos-spending-and-what-does-that

However, in the same piece Bernstein notes that wealthier households’ spending tends to be less influenced by fluctuations in the economy that that of other households. He makes no effort to reconcile these two points – doesn’t actually acknowledge the tension between the two. I’ll give it a go…

The tendency of wealthier households to keep spending through thick and thin is a constant. Reliance on spending by wealth households is high now and equity is highly overvalued by historic measures. So a factor which demonstrates low response to shocks is hit with a big shock – that multiplies out to a moderate overall effect.

A slight tangent: I recall seeing efforts to calculate separate wealth effects for housing and for funancial assets, the result being that housing wealth has a larger effect. One explanation offered was that mortage equity withdrawal allowed ready spending out of housing wealth without liquidation, whereas spending out of financial wealth requires liquidation (but not for rich people). Another explanation is that the rich are so well buffered against shocks that they maintain spending, come rain or come shine, and they own most of the financial assets.

So the “wealth effect” is masked by the effect of wealth. The rich can borrow and draw on cash holdings, so their spending doesn’t respond to fluctuations in wealth in the short term. We, as a culture, had been taught to ignore the rich getting richer in the long run, and didn’t think about long-run wealth effects. Our post-housing-crash reassessment of neo-liberalism means we now think more about those long-run wealth effects, just as they are becoming (dangerously?) large.

Another point about spending by wealthy people is that they have the ability to front run tariffs. They may decide that spending on items they planned for the next year or two (new cars, furniture, appliances) would be better done before tariffs than after. It would be interesting to see whether wealthy people are actually increasing their spending in the first part of this year but currently stabilizing or reducing.

What if we had a Treasury bust instead? Just read the largest foreign holder of Treasury securities (37% percent) is the Cayman Islands via very leveraged hedge funds that are domiciled there and conduct basis trades (FT Alphaville). Of course the trade is made possible by securities lending from MMF and other sources.

The Fed has a new paper:

The Cross-Border Trail of the Treasury Basis Trade

Maybe the 40 billion covers more debt that Argentina. If a trade went bust then the repo’d collateral is gone and the hedge fund has to purchase like issuance for cash and return the securities to the recorded owner. Just a thought.

Might also explain the cram down move.

Artificial Intelligence valuations run on speculation and greed. “We have to get in now before everyone else to get the gains.” Someday, AI may be a foundational tool for the country. Someday. But for now, it is a wobbly, sometimes disastrous tool.

https://www.silicon.co.uk/e-innovation/artificial-intelligence/judge-sanction-ai-lawyer-627065

https://www.nj.com/bergen/2025/09/what-this-nj-lawyer-did-with-ai-landed-him-a-hefty-fine-and-a-warning-to-all-attorneys.html

https://live-computing-data-science-and-society.pantheon.berkeley.edu/news/how-use-ai-discovery-without-leading-science-astray

The key word is “artificial”. Building a portfolio with AI stocks could work out and reap riches, but it could be a tulip bust. If you are investing in AI because “everyone is”, then don’t cry if it doesn’t meet your expectations.

On the other hand, don’t be surprised if an AI bust spills over because it is insinuated into many “mainstream” stocks.

https://www.fool.com/investing/2025/10/19/24-percent-of-buffetts-portfolio-in-3-ai-stocks/