A large portion of GDP growth is accounted for (in a mechanical sense) by capital investment related to AI. What are the prospects for continued spending momentum from this sector, given recent developments in markets?

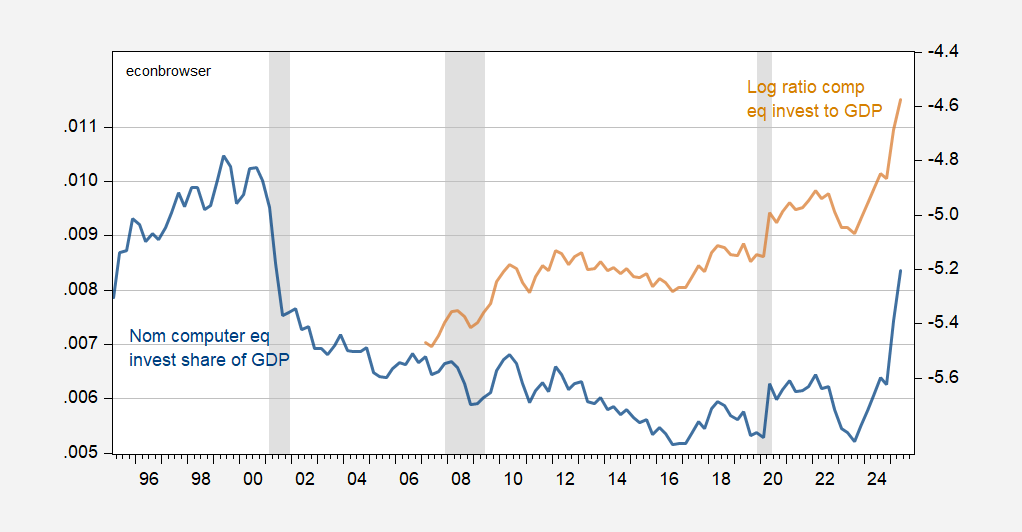

First, here’s a picture of computer equipoment capital investment over time, as a nominal share of GDP and log ratio of real quantities.

Figure 1: Ratio of nominal investment in computer equipment to nominal GDP (blue, left scale), and Log ratio of real investment in computer equipment to real GDP (tan, right scale). NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA via FRED, NBER, and author’s calculations.

There’s been a jump of 0.3 percentage point share of GDP since mid-2023. This data only goes through 2025Q2, given delayed release of NIPA data. Here’s some speculation on overall nonresidential investment:

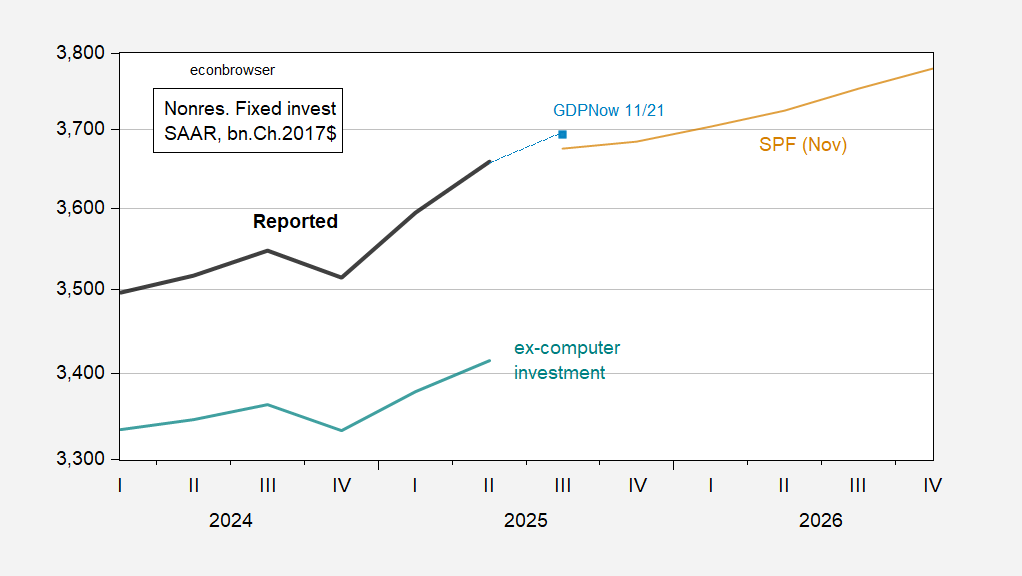

Figure 2: Nonresidential fixed investment (bold black), GDPNow nowcast of 11/21 (light blue square), Survey of Professional Forecasters median (tan), real nonresidential fixed investment minus real computer equipment investment (teal), all in bn.Ch.2017$ SAAR. ex-computer investment series calculated using simple subtraction. Source: BEA, Atlanta Fed, Philadelphia Fed, and author’s calculations.

Overall nonresidential investment growth is nowcasted to have slowed in Q3, and forecasted to slow further going into Q4.

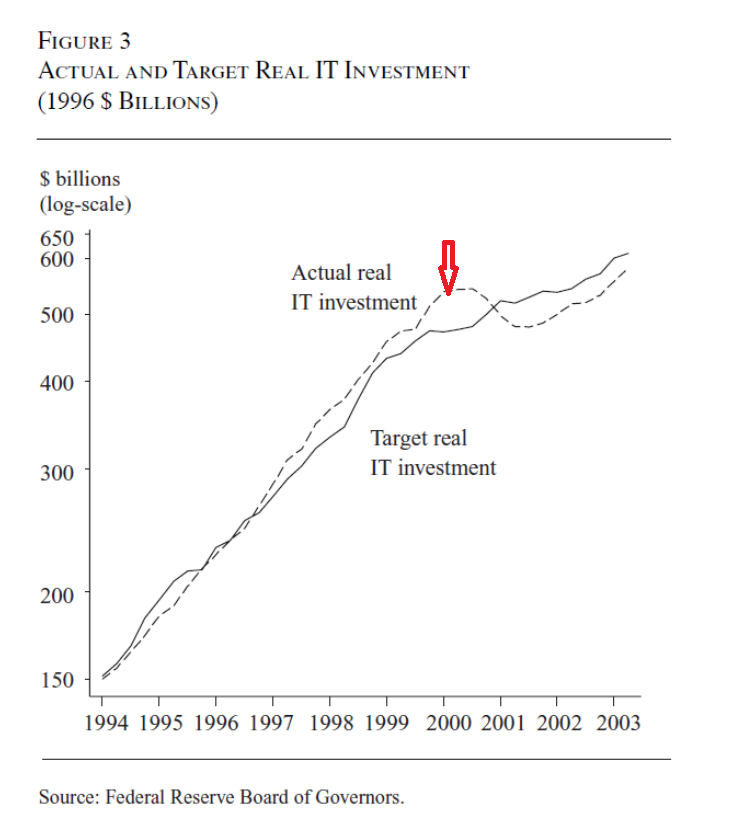

Can we infer anything from stock prices? In 2000, the Nasdaq peaked on March 30. IT investment plateaued in that period, according to Doms (2004).

Source: Doms (2004). Red arrow at Nasdaq peak (edit by author).

In other words, IT spending essentially maxed out at Nasdaq peak, and stayed at that level for another couple quarters.

The Mag-7 index hit a local peak near end-October. Assuming no resumption of rise in the index (and the present repeats the past), then real computer equipment investment is likely to have hit a plateau as well. To the extent that growing investment adds to growth (in an accounting sense), a plateau in investment suggests (holding all else constant) slowing growth.

Source: CNBC, accessed 25 Nov 2025.

Of course, a sustained resumption of Mag-7 price rise would force a big revision in this view.

Industry views suggest that even with a correction in technology-related stock prices, the inertia in AI related spending will sustain investment (equipment, construction, software) for some time (years?) to come.

A rise in capital investment has a long tail, as long as the investment produces a sufficient return. Thay’s because replacement of existing capital is a fairly steady share of the total capital stock. If the capital stock grows in one period, then replacement of capital stock grows in future periods. Likewise, if capital investment as a share of GDP grows in one period, then a larger increment of capital investment in future periods is required simply to replace existing capital.

If returns to investment in AI turn out to be high initially – which remains to be seen – returns to AI investment in the future will necessarily be lower, as a greater share of future investment goes to replace existing capital stock. It’s just the way ofthings, built into the math. Another way of saying this is that an increase in investment as a share of GDP raises the capital/labor ratio in early periods, but is eventually entirely used up in replacing outstanding capital to sumply maintain the new, higher K/L ratio.

Technology optimists often miss this iron law, thinking that an upward shift in capital spending as a share of GDP causes a steady rise in productivity. In reality, an upward shift in K as a share of Y produces a one-time increase in productivity. A step increase in productivity is a good thing, but it pays a far lower return than a persistent rise in productivity.

All of which is to say, it’s going to be damned hard for AI to pay high enough returns to justify the current pace of investment, especially given what we’re learning about borrowing costs for big data centers.

One more issue that I think is worth considering is the incentives facing tech executives. For most of us, “fear of missing out” is an emotional thing, a foible. For tech execs, it’s probably rational. If they jump on the next promised earnings miracle with everybody else, they can hope to be protected if it goes wrong. If their efforts win the day, they can expect a huge payday. The real downside risk in the near term is being replaced by a more aggressive guy who spends more on AI. FOMO is entirely rational for tech execs. Their incentives are not well aligned with shareholder welfare or with social welfare. That’s not a technical argument against AI optimism. It is, however, a reasonable behavioral argument against optimism.

There has been a running debate at Naked Capitalism on “is it a bubble”. Iam beginning to wonder if any of the AI “hyper scalers” (whom Jim Cramer seems to admire) will make many payments on the capital structure before their hyper scales are obsoleted by more resource stingy tech.

That also is conditioned on if the hyper scalers’ revenues near covering costs.

To really date myself, the former Chair of the Council of Economic Advisors under Nixon and Ford, Herb Stein, had a simple axiom. “If something can’t go on for infinity, it won’t.” These might very rich and accomplished men (mostly men it appears), making these investment decisions about AI, but they are as subject to “Group Think” as the rest of us and they are surrounded by men and women whose every incentive is to say “Yes Boss, that’s a great idea” whether the idea or plan is actually any good being irrelevant to pleasing the boss and keeping the gravy chain flowing.

There is another saying, which Barry Ritholz quotes, that “The Market can stay nuts longer than you can stay solvent” about the risks of those betting a bubble will pop. That it will eventually pop is a certainty, but the when is unknowable.