Today, we present a guest post written by Jeffrey Frankel, Harpel Professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, and formerly a member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers. A shorter version was published in The Guardian and in Project Syndicate.

December 31, 2025 — As Donald Trump took office last January, most economists worried that he might adopt the high tariffs he had campaigned on, raising prices of consumer goods and inputs that US households and firms had to pay. The result would be an increase in inflation, at the same time as a fall in real income. As a supply shock, it would not be the sort of development that the Federal Reserve could counteract. The damage would be especially large if other countries chose to retaliate with tariffs of their own.

The tariffs proclaimed by Trump in the subsequent months were substantially worse than most expectations. Announcements were frequent, large, and seemingly disconnected from an economic rationale. They went far beyond the already harmful trade measures of his first term. They departed from what is considered to be Republican free-trade orthodoxy. They went beyond the infamous Smoot-Hawley tariff of 1930 in their severity and disruptiveness. They ignored international agreements that the US had signed.

- Macroeconomic effects

The implication was sure to be large adverse effects on inflation, employment, and real income. Yet, the reality of 2025 turned out not as bad as many economists expected, given the magnitude of the tariffs announced. There was not quite as much retaliation by trading partners as one might have feared. (There has been some, hurting for example American farmers who had been exporting grain to China.)

CPI inflation may not have risen at all. It was 2.7% in the closing months of 2024, and the most recently reported number, for the 12 months ending in November, is the same, 2.7. (Of course, Trump’s claim that the price level has come down is not remotely true.)

The unemployment rate has risen, but only from 4.1 % at the end of 2024, to 4.6 % last month, November. The BEA reports that economic growth was strong in the 3rd quarter; though in the 4th quarter it probably slowed somewhat. In sum, although all the numbers for the year are not in, it is pretty safe to say that the economic damage so far in Trump’s term looks to have been smaller than had been predicted.

Then, are most of the economic effects that were expected in 2025 now due to hit in 2026 instead? Or did we economists have it all wrong from the start?

- Explaining the small effects

There are four reasons why the biggest tariff effects have not shown up in 2025. Bottom line: Expect to see more of the effects in the coming year.

First, is the point that the economic statistics now are more-than-usually vulnerable to measurement error due to the US government shutdown October 1 – November 12. Some CPI data is missing because the BLS could not collect as normal and was never able to gather data on October. There is reason to suspect that even in November, in the absence of some actual new data, housing cost inflation may have been misleadingly recorded as zero. If true, this would bias the overall CPI estimate for October-November downward. [However, we don’t want to get into the habit of explaining away CPI news; that might undermine the credibility of the BLS.]

The shutdown impaired the gathering of other data as well, notably the growth statistics. The BEA is way behind schedule. We must await over the coming months the release of much new information concerning economic performance in the 2nd half of 2025.

The second reason we have seen less effect is that many of the highest tariffs declared by Trump — for example, the so-called reciprocal tariffs announced on the notorious April 2 “Liberation Day” — were postponed (repeatedly) or rolled back when they were seen to raise grocery prices (notably coffee and beef and other foods, on November 15) or made subject to large exceptions (e.g., the imports from Mexico and Canada that were covered by NAFTA/USMCA). It was never likely that he would persist with the very worst of his tariffs, because they would have been so damaging to American business. For example, the integrated North American auto industry would have been devastated, if he hadn’t changed his mind on March 6 and decided to grant the exceptions for Mexico and Canada to the 25 % that had gone into effect two days earlier.

Trump’s tendency to step back from the brink, even if he doesn’t get what he demanded from the other side, has been derided as TACO, “Trump Always Chickens Out.” But when a madman threatens Armageddon, it is foolhardy to goad him into following through. Better that he should chicken out, and so moderate the damage.

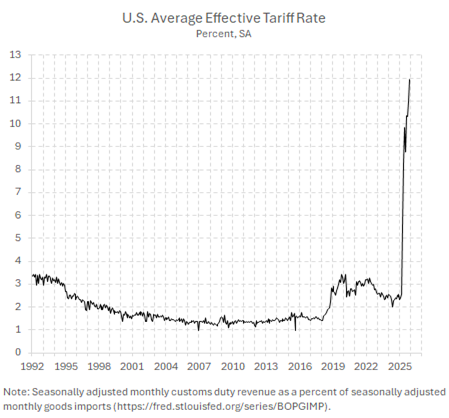

The tariffs that he has in fact put into place are bad enough as they are. According to the Yale Budget Lab, the average effective tariff on US imports has risen from 2 % to 18 %, the highest since the 1930s. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: US tariffs overall increased six-fold in 2025

Source: Pawel Skrzcpynski

The third point is that companies frontloaded imports, between the election in November 2024 and May of 2025, stockpiling a large amount of goods, particularly gold imported from Switzerland and weight-loss drugs imported from Ireland. Even after the tariffs went into full effect, most retailers probably didn’t raise prices until they had used up the high inventories that they had acquired at the lower price. This is common practice among retailers, even though an economist might say that it violates the principle of profit maximization. The strategy of accelerating imports (and altering bilateral purchasing patterns) is estimated by the Penn Wharton Budget Model to have saved importers as much as $6.5 billion, equivalent to 13.1 percent of the new tariff bill through May.

Fourth, and most importantly, even after depleting their pre-tariff inventories, importers have continued to cushion their customers, at least temporarily, by absorbing much of the cost increase into profit margins.

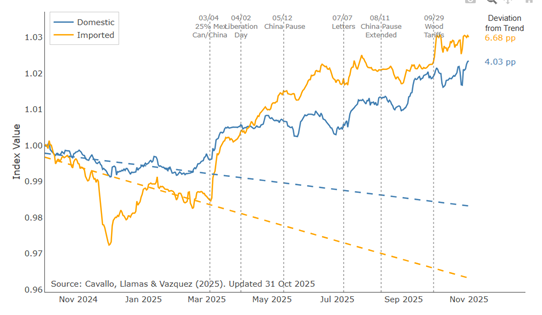

Figure 2: The new tariffs were partly passed through to consumers, starting March 2025

Source: Alberto Cavallo, Paola Llamas and Franco Vazquez, “Tracking the Short-Run Price Impact of U.S. Tariffs,” HBS Working Paper.

- Data from 01/01/24 to 09/08/25.

www.library.hbs.edu/working-knowledge/why-rising-prices-might-feel-worse-now-tariff-trendlines

Alberto Cavallo and co-authors gather real-time data from very large American retailers, on prices of thousands of goods, many of them imported. They find that those items subject to tariffs indeed suffered significant rises starting in April 2025 – not just the imported goods themselves but also the American-made products that are close substitutes (Figure 2). About 5.4 % at the retail level. This is enough to displease alert purchasers of particular products. And it is enough to push the inflation rate on the entire CPI basket up by 0.7% above where it would otherwise have been. But it is a small fraction of the total increase in tariffs that could potentially be passed through.

It is not that foreign exporters are lowering their prices to compensate for tariffs (although Trump claims they are). The prices that importers pay have indeed gone up in proportion to the amount of the tariff. It is, rather, that American firms have, so far, absorbed much of the added cost, rather than fully passing it through to consumers. This is a familiar pattern from studies of delayed and incomplete pass-through of dollar depreciation to American retail prices.

- Tariff uncertainty

One reason American importers have delayed the decision to raise the prices they charge their customers is the tremendous uncertainty over whether the tariffs are here to stay. One never knows when Trump may change his mind or when the Supreme Court may decide to follow the law. This is the same uncertainty that has also discouraged affected American firms from laying off workers. But more of the tariffs’ effects will surely show up in 2026. The distortion and, equally, the uncertainty surrounding the tariffs, will hurt real income for as long as they are in place.

This post written by Jeffrey Frankel.

Minutes of the December FOMC meeting suggest that even the single rate cut pencilled in for next year may not happen:

https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcminutes20251210.htm

Several policy makers who voted for the December rate cut would have been willing to forego the cut. There was a good bit of discussion of whether the inflation fightshould take seco d place to boosting employment. Along with two dissents against the December cut, the minutes show how close the FOMC was to remaining on hold in December – so maybe next year, as well.

More of a confirmation of the state of play than a surprise. Absent tariffs, the inflationary impulse and labor market weakness would be down to immigration policy, so more narrowly focused on services.

New data point on affordability problems:

https://archive.is/mTZqi#selection-2679.4-2679.75

American Consumer Credit Counseling reports that better educated and higher income households are joining the ranks of those struggling with debt in greater numbers. We kinda knew that, but ACCC keeps track and so has data to back it up. The debt problem is, of course, a cost of living problem as well as an income problem. This gets us back to the Fed’s policy dilemma – monetary policy can’t address either problem without making the other one worse.

If only there were a policy (or policies) that would boost employment AND reduce inflation…

The Fed maintained a steady growth rate in nominal GDP of about 5%. That is why the Trump tariffs did not crash the economy.

Trumphal Arch:

https://www.politico.com/news/2025/12/31/trump-arch-washington-dc-america-250-00708590

Guarantee similar spelling is the reason this is happening – another minument to himself.

In these dark times it’s very easy to get discouraged. So I thought I would pass on these two interesting notes, both from NPR. The story based in Maine I share to show there are still many kindhearted Americans out there.

What the orange bastard is angling for is the National Guard and/or ICE to be his brown shirt Nazis. As right wing as many of these folks are (especially the new ones joining up in ICE), I think he’s going to slowly figure out this isn’t going to work like he imagines it. This is why Mark Kelly and Elissa Slotkin have been speaking directly to soldiers and the public about this. Because anyone with two eyes and half an education knows where the orange bastard is trying to shift this.

https://www.npr.org/2025/12/23/nx-s1-5641959/supreme-court-chicago-national-guard

https://www.npr.org/2025/12/31/nx-s1-5616484/wood-banks-in-maine-are-increasing-along-with-the-need-for-heat

What everyone (including left leaning journalists) failed to notice in Slotkin’s and Kelly’s statement/warning was the word ILLEGAL in the phrase “ILLEGAL orders”. Many generals who the orange bastard fired KNEW what the word ILLEGAL in “ILLEGAL orders” meant, that is why trump got rid of so many Generals.