Today, we’re fortunate to have a guest contribution by Jeffry Frieden, Professor of International and Public Affairs and Political Science at Columbia University.

The second administration of President Donald Trump has remade American trade policy. In a new essay, David A. Lake and I survey the historical context for the Trump Administration’s trade strategy, examine the reasons for this dramatic turn in American trade policy, and summarize the likely domestic and international effects of the strategy. The paper is available here.

In this blogpost, I focus on the implications of the Trump trade policies for our analyses of the political economy of international trade. Just as the Trump policies are unprecedented in the post-war period from an economic standpoint – and, on many dimensions, unprecedented in American history more generally – they also represent a serious break with the way trade politics has worked over the past hundred years.

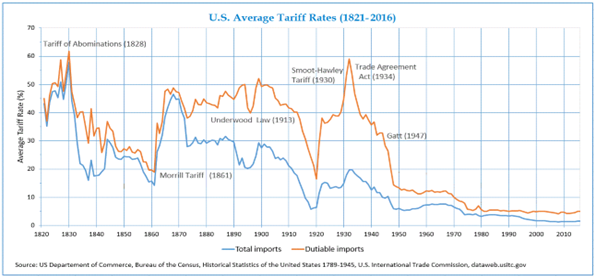

From the founding of the Republic until the 1930s, Congress made trade policy. Periodic trade bills would be cobbled together in the House and Senate, typically by logrolls that included most of the relevant and politically influential protectionist interests. Especially after the Civil War, tariffs were set at very high levels, especially by the Republican Party on behalf of its industrial constituencies in the Northeast and Midwest. Over the course of the early 1900s, new exporting and other internationalist interests grew concerned about the reciprocal impact of our tariffs on those of others; the Democratic Party largely reflected their more pro-trade stance.

In the 1930s, in the depths of the Great Depression, Congress passed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, which delegated a great deal of trade bargaining power to the President. From then on, much trade policy has been managed by the executive branch and its independent agencies (such as the International Trade Commission). The original delegation was intended to impart a more pro-trade, less log-rolling, bias to trade policy, and it largely did so.

The Trump Administration has used a variety of means to take full control of trade policy, facilitated by a Republican Congress that seems content with this. Most of the means in question have to do with declaring the United States to be in one or another state of emergency – economic, national security, or otherwise unspecified. This strategy may not hold up in the courts, but it seems unlikely to matter, as the Administration will undoubtedly find other ways to impose the trade barriers it desires.

The Trump Administration’s trade policy appears to have several aspirations, some of which are not consistent with others. In rough order, Trump wants to rebuild American manufacturing, for both economic and security reasons. This goal may also reflect a political strategy to appeal to regions that have experienced a loss of manufacturing in the Industrial Belt. He also seeks to use tariffs to extract concessions on trade, drugs, and other non-economic issues. Finally, Trump wants tariffs to generate revenue for the government, perhaps to offset Republican tax cuts. The proximate aim is to balance the flow of goods between the United States and each of its trading partners, meaning that U.S. exports of physical goods should equal U.S. imports on a bilateral basis.

Although the dust has far from settled on the Trump trade policies, most analysts expect effective protection to end up in the 15-20 percent range. This is as high as we have seen in a developed country in many decades, and has a wide variety of economic implications.

Whatever the economic significance of these policies, the analytical implications are if anything more significant, for this is a massive departure from the way American (and other) trade policy has been made. The political economy of trade policy has been studied in great detail for many years, and there is a massive theoretical and empirical literature on it, both in the United States and elsewhere. But much of what has happened in American trade policy recently seems to diverge from the typical models we have of the making of trade policy.

Trade policy has generally been understood as a case of classical special-interest politics, in which the interests of producers are pitted against the interests of consumers. The canonical models of trade policy are these days largely subsumed within the Grossman-Helpman “Protection for Sale” framework. This takes into account the degree of organization of the interests, how much political power they have, and the deadweight costs of the policy; the result is a government that weighs the interests of protectionist industries against the interests of industries and individuals that consume imports (and tradables more generally) and aggregate social welfare. Trade policies are not normally particularly partisan, as members of Congress and other politicians of all stripes are primarily concerned about safeguarding the interests of their constituents.

In “normal times,” then, trade policy is special-interest politics, and not very ideological. This has been true in the United States since the 1930s. And yet there have been times when trade policy has been highly partisan, and very ideological. As noted, there were substantial differences between Republicans and Democrats in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and in the interwar period the country was similarly divided between protectionist isolationists and free-trade internationalists.

There are, then, times when trade policy leaves its normal tracks and becomes an issue of national political debate – largely over the very broad outlines of the policy in question, such as between isolationists and internationalists. Indeed, several years ago I helped coordinate a multi-country study for the Inter-American Development Bank about trade policy in Latin America, and we were very interested to find that this pattern was common there as well. In almost all times, trade policy was carried out quietly by special interests and their supporters, at the firm or industry level, with little public attention. But there were periods – often when a major trade treaty was being considered, or in times of crisis – when trade became high politics, and political parties divided bitterly over the broad outlines of the trade strategy to be pursued.

Today’s United States is in one of these periods, in which the nation’s strategy toward trade – and the international economy more broadly – is up for discussion. This is so novel in the last 80 years that it has taken many analysts by surprise, for a “centrist consensus” in favor of economic integration had prevailed in the United States since the 1940s. But the 2016 election was a watershed, in which for the first time in 100 years candidates for the presidential nomination of both parties ran on platforms explicitly hostile to international trade. Indeed, the stump speeches on globalization of both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump were virtually indistinguishable. The first Trump Administration began the turn away from the centrist consensus; the Biden Administration did not really reverse this course; and the second Trump Administration has completed a more or less about-face in American trade strategy.

This does not mean that special interests do not matter. Some traditionally protectionist industries – steel, aluminum, autos – have received protection, and there have been thousands of requests for exemptions from tariffs. In fact, evidence from exemptions granted by the first Trump Administration suggests the relevance of standard political-economy motivations.

Nonetheless, it seems clear that what is in play is a broad strategic view of America’s role in international trade. Post-war American foreign economic policy – like the post-war international economic order more generally – rested on two pillars: American leadership and multilateralism. The current administration has called both these into question. It regards the United States as overstretched and overburdened, and sees multilateralism as inimical to American interests. While there are many, widely held, alternative views, they seem to have gone into hibernation in the face of the Trump Administration’s attempts to reverse the course of American policy.

The contending visions of America’s place in the world are not divorced from economic interests. Just as the isolationist-internationalist divide roughly tracked the economic interests of major American regions and industries, there is a clear division between the generally internationalist coasts and big cities, on the one hand, and the nationalist populists in heartland industrial and agricultural regions. Nonetheless, there are clear ideological and attitudinal distinctions between these world views that are not reducible to economic self-interest.

Competing conceptions of the American national interest in the trade and economic arena clearly relate to questions about the country’s broader role in an increasingly contentious geopolitical environment. China’s rise and Russia’s turn toward revanchist imperialism are significant challenges to the United States and its traditional allies. There are many ways they could be confronted; the Trump Administration has largely chosen unilateral and transactional approaches. This is certainly consistent with its trade policies, which have been unilateral and transactional; but it is hardly the only possible strategy.

Until recently, the modern political economy of trade seemed straightforward: special interests contended for influence over policymakers for policy rents. The Trump Administration’s turn has brought us back toward policy debates more reminiscent of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when parties, regions, and ideologues contested the nation’s appropriate role in the world economy. Those debates implicated alternative views of national security, national purpose, and the national interest. The current debates raise analogous questions about what kind of country the United States is and wants to be, and how it wants to interact with the rest of the world.

This post written by Jeffry Frieden.

Off topic – DOGE grabbed citizens’ private data to steal elections. The DOJ said so in a court filing:

“Doge improperly shared sensitive social security data, DoJ court filing reveals”

“…the so-called “department of government efficiency” (Doge) signed a secret data-sharing agreement with an unidentified political advocacy group whose stated aim was to find evidence of voter fraud and overturn election results in certain states.”

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/jan/21/doge-social-security-data

About that “Board of Peace” idea the felon-in-chief is shopping around…it’s not as civic-minded an idea as it seems.

Aside from the planet-sized dollop of self-aggrandizement and massive opportunity for graft, a permanent UN role would grant the felon permanent diplomatic immunity. Even the Supreme Court is unable to give the felon immunity from state prosecutions, but the UN can.

He has also “appointed” a number of his enablers to positions on the Board, which would presumably put them above the law, too.

Remember that Brazilian kid, Antonio F. Azeredo da Silveira Jr., who shot a bouncer – three times – and got off scot free because of his dad’s diplomatic status? That’s what the felon wants.

To get back on topic…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4NdoWTWwVUQ

He sees more dimensionality in trade policies.

Scott Bessent praised the felon-in-chief, like he’s paid to do. He said “This is what American leadership looks like.” Mark Carney, who is not beholden to the felon, told his Davos audience that U.S. behavior under the felon means the end of U.S. leadership; the U.S. has torn up the covanent between liberal democracies and those democracies will now have to establish new relationships. I respo se, yhe felon uninvited Canada to the “Board of Peace”, not that Carney would have signed Canada up for this billion-a-pop shakedown.

The question before the house is, “Did Bessent give an accurate assessment?” Any emotional red herrings are irrelevant.

Bruce Hall An accurate assessment of what? There isn’t much doubt that globalization improves economic welfare overall. Yes, not everyone benefits, but the benefits far outweigh the costs to those individuals who do lose out, so there’s no economic reason why those economic losers should not be made whole. Of course, there is a political reason, which is that Trump’s oligarchic friends (I’m talking to you Scott Bessent) refuse to tax themselves.

The China Shock thing is real and there are good non-economic arguments why a country should protect critical industries. But would you call bathroom vanities a critical industry? Regardless of how valid those non-economic arguments might be in any one case, it’s still true that a country turning away from globalization comes at an economic cost. We will all be worse off if bad actors like China choose to make themselves worse off by running a mercantilist, export driven economy. It will make us worse off if we have to walk away from globalization, but it will also make the Chinese worse off.

And this gets to another stupid comment that Bessent made. He seems to think the purpose of trade is to generate exports. Wrong. Deeply wrong. That’s an old, discredited mercantilist argument. He’s talking like a parochial businessman rather than a Secretary of the Treasury. The purpose of exports is not to make exporters rich, it’s to pay for imports. That’s something that anyone who has ever studies international trade should know. If you don’t know it, then you might want to buy Menzie’s new book on international trade and finance.

Bessent is right about getting our NATO allies to contribute more to their defense. But he’s right for the wrong reason. The reason the allies should increase their defense spending is so that they will be less dependent up their US hegemon. That would be a good thing for them. But it would be a bad thing for the US because as the NATO hegemon we lose political leverage as our allies become less dependent on us. Of course, their independence also makes multi-polar world more likely, and multi-polar worlds are a lot less stable than bipolar worlds.

Bessent’s comments were obvious nonsense to anyone who understands economics, but he probably sounds smart to Trump’s MAGA base.

Brucie? Who are you to tell us which questions are relevant? If Bessent participates in the destruction of the American way of life, but may have gotten a description of si3me aspect of the economy right, all that matters is that he got something right? He mostly didn’t, but even if he did, who are you to say nothing else matters?

Hey bruce, have you seen the unconstitutional deployment of violence by ice in Minnesota? Pepper spraying people after they have been detained? Using 5 year old children as bait? Shooting us citizens in the face at point blank range? Trump and ice are using gestapo like actions against us citizens with impunity. If you support this action then you dont support the constitution of the usa.

dimensionality? I love it when little Brucie uses big words he has no clue as to their meaning.

So the question is, if a police officer shoots a protester, is it self defense if the protester has a gun? Because all those gun toting texans showing up at protests through the years need to be warned about this risk. You are fair game if you are toting a gun. Right bruce? Maybe ice should think twice before trying to slander the protestors they just murdered.

Video shows agents escalating the situation in order to justify extreme use of force. This is not the america i know. Stop sending in untrained military forces. Jail time is deserved for certain members of dhs who participate or condone this immoral behavior.